Étienne Carjat

Étienne Carjat (28 March 1828 – 19 March 1906) was a French journalist, caricaturist and photographer. He co-founded the magazine Le Diogène, and founded the review Le Boulevard. He is best known for his numerous portraits and caricatures of political, literary and artistic Parisian figures. His best-known work is the iconic portrait of Arthur Rimbaud which he took in October 1871.[1] The location of much of his photography is untraceable after being sold to a Mr. Roth in 1923.

Étienne Carjat | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, c. 1865 | |

| Born | 28 March 1828 |

| Died | 19 March 1906 (aged 77) |

| Occupation | Journalist, caricaturist, photographer |

Biography

Carjat was born in Fareins, a commune in the Ain department in eastern France. When he was ten, his family moved to Paris, and in 1841, at the age of thirteen, he was apprenticed to Mr. Cartier, a silk manufacturer. At first he was employed in mundane activities, but he came to the attention of the chief designer, M. Henry, who was pleased with drawings he had made to amuse children and he was transferred to the design department. He remained there for three years. Interested in the theatre, in 1854 Carjat published a series of lithographic caricatures of Parisian actors, each being accompanied by a comic verse. These proved popular and Carjat later used reproductions to make cartes de visite, and the photographer Pierre Petit produced enlarged versions.

In 1858, Carjat learned the profession of photography from Pierre Petit, and in 1861, he moved into his own workshop at number 56 Rue Laffitte in Paris. This was the same location as the offices of the newspaper Le Boulevard, which he founded, and which was run by his friend Alphonse de Launay. The poet Charles Baudelaire contributed to this weekly magazine.[3] Carjat's photographic skills developed and he produced numerous portraits of celebrity subjects, his photographs being distinguished by the absence of the elaborate ornamentation that other photographers favoured.[4] His photographs captured the spirit of his subjects by their dramatic postures and expressions. His work was recognised internationally, and he received awards in Paris (1863 and 1864), in Berlin (1867), and at the Paris Exposition Universelle (1867). Portrait photography may have been his main interest at this time, but he continued with his editing activities and publishing cartoons in the popular press.[5]

In 1865, he sold his workshop to Légé and Bergeron. From 1866 to 1869, he moved to number 62 Rue Jean-Baptiste-Pigalle, then to 10 Rue Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. He was a friend of the painter Gustave Courbet;[6] (like Courbet) he supported the Paris Commune in 1871, and published political poems in their newspaper La Commune.[7] He continued in his work as a caricaturist, published in particular in the newspaper Le Diogène of which he was the co-founder. He also published a book, Artiste et citoyen, in 1883.

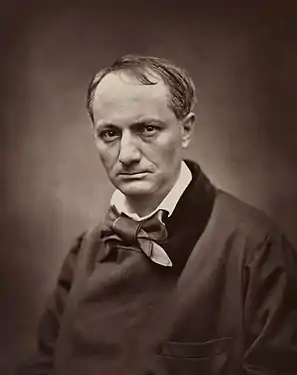

One of his best-known photographs is a portrait of Arthur Rimbaud, taken in October 1871. Paul Verlaine, Rimbaud and Carjat were part of Vilains Bonshommes, a group created in 1869, which brought together poets and artists like André Gill, Théodore de Banville and Henri Fantin-Latour. In January 1872, a quarrel broke out during a dinner organized by this group, and Rimbaud injured Étienne Carjat with the cane-sword of Albert Mérat. In reaction, Étienne Carjat erased the photographic plates corresponding to the portraits he had taken of Rimbaud, and only eight prints of the original photographs survive.[8] Another well-known photograph is a brooding portrait of the poet Charles Baudelaire.[9]

Publications

- Croquis biographiques (1858)

- Les Mouches vertes, satire (1868)

- Peuple, prends garde à toi ! Satire électorale (1875)

- Artiste et citoyen: poésies; précédées d'une lettre de Victor Hugo (1883)

Photographs and caricatures

References

- "How Arthur Rimbaud became the blueprint for outsider teen fashion". Document Journal. 28 March 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Flood, Alison (18 June 2014). "Baudelaire dismissed Victor Hugo as 'an idiot' in unseen letter". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Champsaur, Félicien (1879). Etienne Carjat. A. Cinqualbre. pp. 2–3.

- "Étienne Carjat". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Fallaize, Elizabeth (1987). Etienne Carjat and " Le Boulevard " (1861-1863). Slatkine. p. 36. ISBN 9782051008037.

- Tillier, Bertrand (2004). La Commune de Paris, révolution sans images?: politique et représentations dans la France républicaine (1871-1914). Champ Vallon. p. 82. ISBN 9782876733909.

- Jeancolas, Claude (1998). Passion Rimbaud: l'album d'une vie. Textuel. p. 83. ISBN 9782909317663.

- "Charles Baudelaire". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Étienne Carjat. |

.jpg.webp)