Škocjan Caves

Škocjan Caves (pronounced [ˈʃkɔːtsjan]; Slovene: Škocjanske jame, Italian: Grotte di San Canziano) is a cave system in Slovenia. Due to its exceptional significance, Škocjan Caves was entered on UNESCO’s list of natural and cultural world heritage sites in 1986. International scientific circles have thus acknowledged the importance of the caves as one of the natural treasures of planet Earth. Ranking among the most important caves in the world, Škocjan Caves represents the most significant underground phenomena both on the Karst Plateau and in Slovenia. Following independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, Slovenia committed itself to actively protecting the Škocjan Caves area and established Škocjan Caves Regional Park and its managing authority, the Škocjan Caves Park Public Service Agency.[2]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Slovenia |

| Criteria | Natural: (vii), (viii) |

| Reference | 390 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th session) |

| Area | 413 ha (1,020 acres) |

| Website | www |

| Coordinates | 45°40′N 14°0′E |

| Official name | Skocjanske Jame |

| Designated | 21 May 1999 |

| Reference no. | 991[1] |

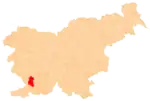

Location of Škocjan Caves in Slovenia | |

Škocjan Caves – World Heritage – UNESCO

- One of the largest known underground canyons in the world

- Examples of natural beauty with great aesthetic value

- Due to particular microclimatic conditions, a special ecosystem has developed

- The area has great cultural and historical significance as it has been inhabited since the prehistoric times

- A typical example of contact karst[3]

Description

Škocjan Caves represents the most significant underground phenomena in both the Karst region and Slovenia.[4] Škocjan Caves was also entered on the List of Ramsar wetlands of international importance on 18 May 1999. Together with the underground stream of the Reka River, they represent one of the longest karst underground wetlands in Europe.

Explored length of caves is 6,200 m (20,300 ft), caves have formed in 300-metre-thick (980 ft) layer of Cretaceous and Paleocene limestone.

The Reka River disappears underground at Big Collapse Doline (Slovene: Velika Dolina) into Škocjan Caves and then flows underground for 34 km (21 mi) surfacing near Monfalcone where it contributes approximately one third of the flow of the Timavo River, which flows 2 km (1.2 mi) from the Timavo Springs to the Adriatic Sea.[5] The view of the big river in the rainy season, as it disappears underground at the bottom of Big Collapse Doline, 160 m (520 ft) below the surface, is both majestic and frightening.

The exceptional volume of the underground canyon is what distinguishes Škocjan Caves from other caves and places it among the most famous underground features in the world. The river flowing through the underground canyon turns northwest before the Cerkvenik Bridge and continues its course along Hanke's Channel (Slovene: Hankejev kanal). This underground channel is approximately 3.5 km (2.2 mi) long, 10 to 60 m (33 to 197 ft) wide and over 140 m (460 ft) high. At some points, it expands into huge underground chambers. The largest of these is Martel's Chamber with a volume of 2.2 million cubic metres (78 million cubic feet) and it is considered the largest discovered underground chamber in Europe and one of the largest in the world. The canyon of such dimensions nevertheless ends with a relatively small siphon: one that cannot deal with the enormous volume of water that pours into the cave after heavy rainfall, causing major flooding, during which water levels can rise by more than one hundred metres (330 ft).[6]

History of exploration

The first written sources on Škocjan Caves originate in the era of Antiquity (2nd century B.C.) by Posidonius of Apamea and they are marked on the oldest published maps of this part of the world; for example the Lazius-Ortelius map from 1561 and Mercator's Novus Atlas from 1637. The fact that the French painter Louis-François Cassas (1782) was commissioned to paint some landscape pieces also proves that in the 18th century the caves were considered one of the most important natural features in the Trieste hinterland. His paintings testify that at that time people visited the bottom of Big Collapse Doline (Slovene: Velika dolina). The Carniolan scholar Johann Weikhard von Valvasor described the sink of the Reka River and its underground flow in 1689.

In order to supply Trieste with drinking water, an attempt was made to follow the underground course of the Reka River. The deep shafts in the Karst were explored as well as Škocjan Caves. The systematic exploration of Škocjan Caves began with a speleology expedition in 1884. Explorers reached the banks of Mrtvo jezero (Dead Lake) in 1890. The last major achievement was the discovery of Silent Cave (Slovene: Tiha jama) in 1904, when some local men climbed the sixty-metre (200 ft) wall of Müller Hall (Slovene: Müllerjeva dvorana). The next important event took place in 1990, nearly 100 years after the discovery of Dead Lake (Slovene: Mrtvo jezero). Slovenian divers managed to swim through the siphon Ledeni dihnik and discovered over 200 m (660 ft) of new cave passages.[6]

Archaeology

From time immemorial, people have been attracted to the gorge where the Reka River disappears underground as well as the cave entrances. The Reka River sinks under a rocky wall; on the top of it lies the village of Škocjan, after which the caves are named. Škocjan Caves Regional Park is archaeologically extremely rich; it was inhabited beginning more than ten thousand years ago. A valuable archaeological find in Fly Cave (Slovene: Mušja jama) indicates the influence of Greek civilization, where a cave temple was located after the end of the Bronze Age and in the Iron Age. This region was certainly one of the most significant pilgrimage sites in Europe, three thousand years ago, especially in the Mediterranean, where it was of important cult significance in connection with the afterlife and communication with ancestral spirits.[7]

Tourism

It is difficult to establish when tourism in Škocjan Caves truly commenced. According to some sources, in 1819, the county councilor Matej Tominc (Tominc Cave is named after him) ordered that steps be built to the bottom of Big Collapse Doline (Slovene: Velika Dolina). According to other sources, the steps were only renovated. A visitors' book was introduced 1 January 1819. This date is considered the beginning of modern tourism in Škocjan Caves.

In recent years, Škocjan Caves has had around 100,000 visitors per year. The first part of the Caves—Marinič Cave and Mahorčič Cave with Little Collapse Doline (Slovene: Mala Dolina)—was opened to tourists by 1933. It was severely damaged in a flood in 1963. In 2011, it was renovated and a new steel bridge was added.[8] Visitors can also view the part of the underground canyon with Big Collapse Doline (Slovene: Velika Dolina). Tours of the cave are conducted in Slovenian, English, Italian and German.

References

- "Skocjanske Jame". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "The Škocjan Caves". Archived from the original on 20 May 2009.

- "Nomination to the World Heritage List" (PDF). Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "Škocjan Caves - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "LTER-Slovenia > Project Overview". Lter.zrc-sazu.si. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Kranjc, Andrej (2002). "Zgodovinski pregled in opis jam" [A Historical Overview and Description of the Caves]. Park Škocjanske jame [The Škocjan Caves Park] (in Slovenian). Škocjan Caves Park. pp. 42–57.

- Turk, Peter (2002). "Archaeology". In Peric, Borut (ed.). The Škocjan Caves Regional Park. Park Škocjanske jame. pp. 86–97. ISBN 9612381283.

- Kuhar, Špela; Struna Bregar, Ana (24 February 2012). "Mostovi kot znamenitost" [Bridges as a Landmark]. Mladina.si (in Slovenian) (8).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Škocjan Caves. |

- Park Škocjanske jame official website

- Škocjan Caves - UNESCO World Heritage Centre listing

- Photos of Škocjan Caves

- Škocjan Caves at Slovenia Landmarks