1835 Philadelphia general strike

The 1835 Philadelphia general strike took place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the first general strike in North America and involved some 20,000 workers who struck for a ten-hour workday and increased wages. The strike ended in complete victory for the workers.[1]

| Philadelphia general strike of 1835 | |

|---|---|

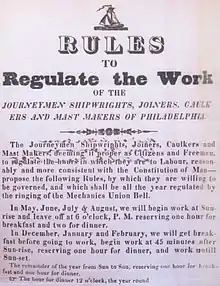

Carpenter's Association banner promoting the ten-hour workday, 1835 | |

| Date | June 6–22, 1835 |

| Location | |

| Methods | Striking |

| Resulted in | Ten-hour workday, wage increase |

Background

Prior to the shorter work day movement, employers had hired and paid workers on the basis of the agriculture working day of "sun to sun" (sunrise to sunset) – a situation which meant comparatively short hours in the winter months but days extending to as many as fifteen hours during the late spring and early summer.[2] For some trades this worked out to a manageable average over the course of a year, but for the construction trades in particular, a business marked by heavy unemployment during the winter months owing to the weather, this state of affairs was regarded as an intolerable burden.[2] As a result, the idea emerged that the length of the work day should be fixed by time rather than the rise and fall of the sun, and agitation for a ten-hour day began.[3]

Boston circular

During the 1820s and 1830s, a number of strikes were commenced to shorten the work day. In June 1827 some 600 Philadelphia journeymen carpenters – that is, the wage laborers employed by master carpenters – went on strike for the citywide establishment of the ten-hour day.[3] Carpenters in Boston, Massachusetts similarly struck for a ten-hour workday in 1825 and 1832. However, the strikes were unsuccessful at shortening the work day.[4]

In 1835 Boston carpenters went on strike again for a ten-hour workday and were soon joined by masons and stone-cutters. The strikers chose Seth Luther and two other workers as leaders, and they issued a circular stating their demands.[5] The circular read in part "We have been too long subjected to the odious, cruel, unjust and tyrannical system which compels the operative mechanic to exhaust his physical and mental powers. We have rights and duties to perform as American citizens and members of society, which forbid us to dispose of more than ten hours for a day's work."[4]

During the strike, the Boston workers organized a travelling committee and requested the assistance of workers in other cities. The Boston circular was well received by workers throughout the country. Although the Boston strike was eventually defeated, the circular was pivotal in motivating workers in Philadelphia to organize their own strike that year for a ten-hour workday. The president of the Carpenter's Society of Philadelphia, William Thompson, told Seth Luther that "the carpenters considered the Boston circular had broken their shackles, loosened their chains, and made them free from the galling yoke of excessive labor."[5]

General strike

Influenced by events in Boston, unskilled Irish workers on the Schuylkill River coal wharves the same year went on strike for a ten-hour day. Three hundred workers marched on the coal wharves. They were led by a worker with a sword who threatened death to anyone who crossed the picket line and unloaded coal from the 75 vessels waiting in the water.[6] The coal heavers were soon joined by workers from many other trades, including leather dressers, printers, carpenters, bricklayers, masons, house painters, bakers, and city employees.[1]

On June 6, a mass meeting of workers, lawyers, doctors, and a few businessmen, was held in the State House courtyard. The meeting unanimously adopted a set of resolutions giving full support to the workers' demand for wage increases and a shorter workday, as well as increased wages for women workers and a boycott of any coal merchant who worked his men more than ten hours.[7]

The strike quickly came to a close after city public works employees joined the action. The Philadelphia city government announced that the "hours of labour of the working men employed under the authority of the city corporation would be from 'six to six' during the summers season, allowing one hour for breakfast, and one for dinner."[8] On June 22, three weeks after the coal heavers initially struck, the ten-hour system and an increase in wages for piece-workers was adopted in the city.[1]

Aftermath

The news of the strikers' success spread to other cities and was given large coverage. The labor press carried the news as far south as the Carolinas, and a wave of successful strikes followed in its wake. Strikes for the ten-hour day hit towns such as New Brunswick and Paterson, New Jersey, Batavia and Seneca Falls, New York, Hartford, Connecticut, and Salem, Massachusetts. By the end of 1835, the ten-hour day had become the standard for most city laborers who worked by the day with the exception of workers in Boston. Subsequently, the ten-hour day became an integral part of the labor movement in Europe.[9][1]

See also

References

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 1, From Colonial Times to the Founding of The American Federation of Labor, International Publishers, 1975, pages 116–118

- Sumner, "Citizenship," pp. 186-187.

- Sumner, "Citizenship," pg. 186.

- Commons, ed., Documentary History of American Industrial Society, Vol. VI, page 96

- Bernstein, Leonard (1950-06-30). "The Working People of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the General Strike of 1835". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 74 (3): 336–337.

- Bernstein, Leonard (1950-06-30). "The Working People of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the General Strike of 1835". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 74 (3): 337.

- Commons, ed., Documentary History of American Industrial Society, Vol. VI, page 39

- Proceedings of the Government and Citizens of Philadelphia on the Reduction of the Hours of Labor, and Increase of Wages, pages 4-10

- Bernstein, Leonard (1950-06-30). "The Working People of Philadelphia from Colonial Times to the General Strike of 1835". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 74 (3): 339.