1912 Ottoman general election

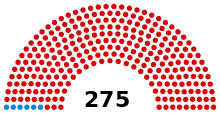

Early general elections were held in the Ottoman Empire in April 1912. Due to electoral fraud and brutal electioneering, which earned the elections the nickname Sopalı Seçimler ("Election of Clubs"), the ruling Committee of Union and Progress won 269 of the 275 seats in the Chamber of Deputies,[1][2] whilst the opposition Liberal Entente (also known as the Freedom and Accord Party or the Liberal Union) only won six seats.[3]

| ||||||||||||||||

275 seats in the Chamber of Deputies 138 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

This lists parties that won seats. See the complete results below. | ||||||||||||||||

Background

The elections were announced in January 1912, after the CUP lost a by-election to the Entente in Istanbul in December 1911.[4] The CUP had hoped early elections would thwart the efforts of the Entente to better organise itself.[2] The CUP platform represented centralist tendencies, whilst the Entente promoted a more decentralised agenda, including supporting allowing education in local languages.[2]

Campaign

Although the two main parties competing in the election, the Committee of Union and Progress and the Liberal Entente, were largely secular in their political outlook, issues such as the Islamic religious piety of their candidates became sensationalized election topics. Seeing the potent amount of political capital to be gained by appealing to religion, as the Muslim vote was the most important in the Empire, both parties consistently accused one another of various other supposed offenses against Islamic tradition.[5]

Entente members accused the CUP candidates of a "disregard for Islamic principles and values" and of "attempting to restrict the prerogatives of the sultan-caliph", despite the fact that many Entente members were quite progressive in their own lives and dealings.[5] In return, the CUP, seeing that its previous policy of secular Ottomanism (Ottoman nationalism) was failing, turned to a similar line of Islamist rhetoric as the Entente in order to drum up support among the Muslims of the Empire; it accused the Entente of "weakening Islam and Muslims" by trying to separate the Ottoman sultan's office from the Caliphate.[5] Although this accusation was almost identical to the one leveled by the Entente at the CUP itself, it was highly effective.[5] The Entente retorted by claiming that the CUP, in its previous attempt to amend the constitution, was covertly trying to "denounce" and abolish the ritual fasting during the month of Ramadan and the five daily prayers.[5]

Aftermath

The manner of the CUP's victory led to the formation of the Savior Officers, whose aim was to restore constitutional government. After gaining support from the army in Macedonia, the Officers demanded government reforms. Under pressure, prominent politician Mehmed Said Pasha and then later the Grand Vizier resigned.[1] Sultan Mehmed V then appointed a new cabinet supported by the Officers and the Entente.[1]

On 5 August 1912, Mehmed V called for early elections. However, with the election underway in October, the outbreak of the Balkan Wars led to it being interrupted.[2] Fresh elections were eventually held in 1914.

References

- The Decline of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East and the 'Arab Awakening' before 1914 Archived 2012-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Hasan Kayalı (1995) "Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1919" International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp 265–286

- Myron E. Weiner, Ergun Özbudun (1987) Competitive Elections in Developing Countries, Duke University Press, p334

- Hasan Kayalı (1997) Arabs and Young Turks University of California Press

- Hasan Kayalı (1995) "Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1919" International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp 273–274. "The prominent leaders of the Entente [Freedom and Accord Party] were Turkish-speaking and no different from the Unionists as far as their basic attitudes toward Islam were concerned. Nevertheless, they sought to frustrate the CUP by encouraging non-Turkish groups to attack it for pursuing a policy of Turkification and by pointing out to the conservatives its alleged disregard for Islamic principles and values. The overall effect of this propaganda was to instill ethnic and sectarian-religious discord, which survived the Entente's defeat at the polls ... The Unionists proved to be less vulnerable to accusations of disregard for Islamic precepts and values. Some of the Entente members were known for their cosmo- politan attitudes and close relations with foreign interests. But this did not keep the Entente from accusing the CUP of violating Islamic principles and attempting to restrict the prerogatives of the sultan-caliph in its pamphlets. One such pamphlet, Afiksoz (Candid Words), appealed to the religious-national sentiments of Arabs and claimed that Zionist intrigue was responsible for the abandonment of Libya to the Italians. Such propaganda forced the CUP to seize the role of the champion of Islam. After all, the secular integrationist Ottomanism that it had preached was failing, and the latest manifestation of this failure was the Entente's appeal to segments of Christian communities. The Unionists used Islamic symbols effectively in their election propaganda in 1912. They accused the Entente of trying to separate the offices of the caliphate and the sultanate and thus weakening Islam and the Muslims. There seemed no end to the capital to be gained from the exploitation and manipulation of religious rhetoric. In Izmir, the Entente attacked the CUP's intention to amend Article 35 of the constitution by arguing that the Unionists were thus denouncing the "thirty" days of fasting and "five" daily prayers. This led the town's mufti to plead that "for the sake of Islam and the welfare of the country" religion not be used to achieve political objectives. As with the rhetoric on Turkification, Islam too remained in political discourse long after the elections were over."