1917 Guatemala earthquake

The 1917 Guatemala earthquake was a sequence of tremors that lasted from 17 November 1917 through 24 January 1918. They gradually increased in intensity until they almost completely destroyed Guatemala City and severely damaged the ruins in Antigua Guatemala that had survived the 1773 Guatemala earthquakes.

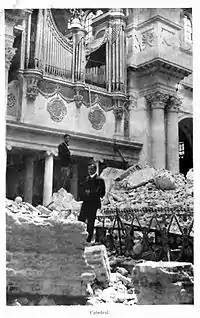

Guatemala City Cathedral after the earthquakes | |

Guatemala City | |

| UTC time | ?? |

|---|---|

| ISC event | n/a |

| USGS-ANSS | n/a |

| Local date | November 1917 to January 1918 |

| Magnitude | M 5.6 (25 December 1917) |

| Depth | 5 km (3.1 mi) |

| Epicenter | 15.32°N 89.1°W |

| Areas affected | Guatemala |

| Aftershocks | Several |

| Casualties | 250 dead |

History

The seismic activity started on 17 November 1917 and ruined several settlements around Amatitlán. On 25 and 29 December of the same year, and on 3 and 24 January of the next, there were stronger earthquakes felt on the rest of the country, which destroyed a number of buildings and homes in both Guatemala City and Antigua Guatemala. Sometimes the movement was up and down, then sideways. At every new shock a handful of houses went down.[1] In most of the houses, walls cracked in two and then roofs fell in; in churches, bell towers crashed down, burying adjacent buildings and their occupants.[2]

Among those buildings destroyed by the earthquakes were a lot of the infrastructure built by general José María Reyna Barrios and president Manuel Estrada Cabrera, whose legacy has been forgotten by Guatemalans. The Diario de Centro América, a semi-official newspaper owned in part by President Estrada Cabrera, spent more than two months issuing two numbers a day reporting on the damage, but after a while, started criticizing the central government after the slow and inefficient recovery efforts.[3]

One of its articles said that some holy Jesus images from the city had been saved because they had been taken away from their churches after the first earthquake as they "did not want to stay anymore in a city where excessive luxury, impunity and terror were rampant".[3] Likewise, the newspaper reported that the National Assembly was issuing "excellent" laws, but nobody was "going by the law". [3] Finally, on its front page of May 1918, it said that there was "still debris all over the city".[3] The Diario de Centro América itself was print in the rubble, in spite of which it was able to issue its two daily numbers.[4]

The French magazine L'Illustration on its 12 January 1918 issue[5] reported on a telegraph cable from 31 December 1917 that Guatemala city had been completely destroyed: two hundred thousand people were left homeless and there were about two thousand deaths. The city's monuments were lost.[5] In 1920, Prince Wilhelm of Sweden arrived to Guatemala on a trip along Central America;[6] his journey took him to Antigua Guatemala and Guatemala City where he saw that the recovery efforts were still not done and the city still lay in ruins. There was still dust whirling in thick clouds, penetrating everywhere – clothes, mouth and nostrils, eyes and skin pores – visitors got sick until they got used to the dust; the streets were not paved and only one in three houses was occupied, as the others were still in ruins.[1]

Public buildings, schools, churches, the theater, and museums were all in the hopeless state of desolation in which they were left by the earthquake. Bits of roof hung down the outsides of the walls and the footway was littered with heaps of stucco ornaments and shattered cornices. A payment of some hundred dollars would ensure that a house that had been marked as insecure with a black cross was then deemed as done with its necessary repairs, allowing the owners to leave the houses empty and in ruins.[7]

It was at the Guatemala City General Cemetery that the devastation was most evident: all was demolished on the night of the earthquake and it was said that about eight thousand dead were shaken from their graves, threatening pestilence to the city and forcing the authorities to burn all of them in a gigantic bonfire.[7] The empty tombs were still open in 1920 and no attempt had been made to restore the cemetery to its original condition.[7]

Finally, Prince Wilhelm, pointed out that the world had sent help in the form of money and goods, which arrived by shipload in Puerto Barrios, but neither helped the city because millions found their way to the President's treasury and his ministers sent provisions to Honduras and sold them there for a good profit.[2]

Aftermath

The earthquakes marked the beginning of the end of the long presidency of lawyer Manuel Estrada Cabrera, who had been ruling in the country since 1898; firm opposition to his regime started after it became evident that the President was incapable of leading the recovery efforts. For instance, in an interview done in 1970, German literary critic Günter W. Lorenz asked 1967 Literature Nobel Laureate Miguel Ángel Asturias why he started writing; to his question, Asturias replied: "Yes, at 10:25 p.m of 25 December 1917, an earthquake destroyed my city. I remember seeing something like an immense cloud covering the moon. I was in a cellar, a hole in the ground or a cave, or something like that. Right there and then I wrote my first poem, a goodbye song to Guatemala. Later on I was really mad by the circumstances under which the rubble was removed and by the social injustice that became really apparent then."[8] This experience prompted Asturias to start writing when he was 18 years old; he wrote a tale called The political beggars (Los mendigos políticos), which eventually became his most famous novel: El Señor Presidente.[9]

Bishop of Facelli, Piñol y Batres from the Aycinena family, began preaching against the government policies in the San Francisco Church in 1919, instructed by his cousin, Manuel Cobos Batres. For the first time, the Catholic Church opposed the President; additionally, Cobos Batres was able to inflame the nationality sentiment of conservative criollo leaders José Azmitia, Tácito Molina, Eduardo Camacho, Julio Bianchi and Emilio Escamilla into forming a Central America Unionist party and oppose the strong regime of Estrada Cabrera. The Unionist party began its activities with the support of several sectors of the Guatemala City society, among them the Universidad Estrada Cabrera students and the labor associations, who under the leadership of Silverio Ortiz founded the Patriotic Labor Committee.[10] After a long struggle, Estrada Cabrera was finally overthrown on 14 April 1920.

See also

Notes and references

References

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 167.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 168.

- Diario de Centro América 1918, p. Front page.

- Foro Red Boa 2012, p. 2.

- Caverbel 1918, p. 48.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 167–179.

- Prins Wilhelm 1922, p. 169.

- Lorenz 1994, p. 159–163.

- Himelblau 1973, p. 43–78.

- Ortiz Rivas 1922.

Bibliography

- Arévalo Martínez, Rafael (1945). ¡Ecce Pericles! (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barrios Vital, Jenny Ivette (2006). Restauración y revitalización del complejo arquitectónico de la Recolección (PDF) (Thesis) (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tesis de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Retrieved 2 September 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caverbel, Louis (1918). "Au Guatemala". L'Illustration (in French). París, France (3906).

- Diario de Centro América (1918). "Cobertura del cataclismo". Diario de Centro América (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tipografía La Unión.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foro Red Boa (2012). "Historia del Diario de Centro América" (PDF). Foro red boa (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Himelblau, Jack (1973). ""El Señor Presidente": Antecedents, Sources and Reality". Hispanic Review. 40 (1): 43–78. doi:10.2307/471873. JSTOR 471873.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lorenz, Gunter W. (1994). "Miguel Ángel Asturias with Gunter W. Lorenz (interview date 1970)". In Krstovic, Jelena Krstovic (ed.). Hispanic Literature Criticism. Detroit, MI: Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-8103-9375-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ortiz Rivas, Silverio (1922). Reseña histórica de la parte que el elemento obrero tuvo en el Partido Unionista (in Spanish). Guatemala: unpublished.

Partially reproduced in ¡Ecce Pericles! by Rafael Arévalo Martínez

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Prins Wilhelm (1922). Between two continents, notes from a journey in Central America, 1920. London, UK: E. Nash and Grayson, Ltd. pp. 148–209.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Recinos, Adrían (1922). La Ciudad de Guatemala, crónica histórica desde su fundación hasta los terremotos de 1917–1918 (in Spanish). Guatemala.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)