1935 Atlantic hurricane season

The 1935 Atlantic hurricane season included the Labor Day hurricane, the most intense tropical cyclone to ever strike the United States or any landmass in the Atlantic basin. The season ran from June 1 through November 15, 1935.[1] Ten tropical cyclone developed, eight of which intensified into tropical storms. Five of the tropical storms strengthened into hurricanes, while three of those reached major hurricane intensity.[nb 1][3] The season was near-normal for activity and featured five notable systems. The second storm of the season sank many ships and vessels offshore Newfoundland, causing 50 fatalities. In early September, the Labor Day hurricane struck Florida twice – the first time as a Category 5 hurricane – resulting in about 490 deaths and $100 million (1935 USD) in damage along its path.[nb 2]

| 1935 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 15, 1935 |

| Last system dissipated | November 14, 1935 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Three (Third most intense hurricane in the Atlantic basin) |

| • Maximum winds | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 892 mbar (hPa; 26.34 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 10 |

| Total storms | 8 |

| Hurricanes | 5 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 2,761 total |

| Total damage | > $126 million (1935 USD) |

| Related article | |

Late in September, the Cuba hurricane struck the country as a Category 3 and later the Bahamas as a Category 4. The hurricane caused 52 fatalities and roughly $14.5 million in damage. The Jérémie hurricane caused significant impacts in Cuba, Haiti, Honduras, and Jamaica in the month of October. Overall, the storm was attributed to about 2,150 deaths and $16 million in damage, with more than 2,000 fatalities in Haiti alone. The Yankee hurricane struck the Bahamas and Florida in early November. The system resulted in 19 deaths, while damage totaled roughly $5.5 million. Collectively, the tropical cyclones of the 1935 Atlantic hurricane season caused roughly $126 million in damage and 2,761 fatalities.

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 106 units,[4] ranking it as a near-normal year.[5] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACE. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical or subtropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold of tropical storm strength.[6]

Timeline

Systems

Tropical Storm One

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 15 – May 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

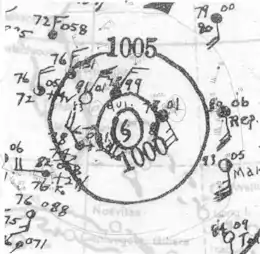

Historical weather maps and ship data indicate that a low-pressure area developed into a tropical depression about 105 mi (170 km) south of Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, at 00:00 UTC on May 15.[3] The depression moved north-northwestward and made landfall in Santo Domingo Este, Dominican Republic, about 12 hours later. After emerging into the Atlantic Ocean near the Turks and Caicos Islands, the cyclone intensified and became a tropical storm around 12:00 UTC on May 16. The storm then began to curve northeastward and accelerate.[7] On May 18, the Dutch ship Magdala observed sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 1,003 mbar (29.6 inHg), marking the storm's peak intensity. The system was absorbed by a frontal boundary by 00:00 UTC on May 19,[3] about 860 mi (1,385 km) east-southeast of Bermuda.[7]

Hurricane Two

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 16 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) < 955 mbar (hPa) |

Data from ships and nearby Windward Islands indicate that a tropical depression formed approximately 275 mi (445 km) southeast of Barbados around 06:00 UTC on August 16.[3][7] The depression tracked north-northwestward and intensified into a tropical storm around 00:00 UTC on August 18, while situated between the islands of Antigua and Barbuda. Continuing north-northwestward, the cyclone intensified into a hurricane while north of the Lesser Antilles at 00:00 UTC on August 19. Curving west-northwest, the storm gradually intensified into a Category 2 hurricane the following day. On August 20, the system began to curve northward and later north-northeastward. The cyclone peaked with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) on August 22, but weakened to a minimal Category 3 hurricane with winds of 115 mph (195 km/h) by the time it passed just west of Bermuda later that day. On August 24, the storm weakened to a Category 2 hurricane and began to turn more northward. Continuing to curve northwestward on August 25, the system continued to weaken to a Category 1 hurricane, later striking Newfoundland as an extratropical cyclone on August 26. The storm dissipated later that day.[7]

Penned as Newfoundland's "worst gale in 36 years,"[8] the remnants of the hurricane battered the island with damaging winds.[8] Charlottetown in Prince Edward Island received 5.6 in (140 mm) of rain over a three-day span. In St. John's, Newfoundland, wind gusts averaged 52 mph (83 km/h) and caused extensive property damage. Total losses were estimated in the thousands of dollars.[9] Communication lines across the island were downed, though the greatest effects were felt offshore.[8] Gale-force winds and rough seas wrecked multiple schooners off the coast of Newfoundland, claiming an estimated 50 lives.[10] Every ship that set sail within a day of the storm was damaged.[11] Six people drowned when Walter sank near Trepassey.[12] The SS Argyle was dispatched on search and rescue for three other vessels; however, upon discovery of the ships they reported no sign of life and their crew are believed to have been washed overboard.[13] In the days following the storm, wrecks of schooners, such as the Carrie Evelyn, washed ashore.[10]

Hurricane Three

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 29 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-min) 892 mbar (hPa) |

The Great Labor Day Hurricane of 1935

An area of disturbed weather developed into a tropical depression around 06:00 UTC on August 29 while situated roughly 200 mi (320 km) northeast of the Turks and Caicos Islands.[3][7] The depression initially strengthened slowly as it moved west-northwestward and then westward, reaching tropical storm intensity by early on August 31. Later that day and on the following day, the system passed through the Bahamas and reached hurricane intensity around 12:00 UTC on September 1. After passing near the south end of Andros Island, the storm rapidly intensified while moving across the Straits of Florida, achieving major hurricane status by 06:00 UTC on the next day. At approximately 00:00 UTC on September 3, the cyclone intensified into a Category 5 hurricane, with winds peaking at 185 mph (295 km/h).[7] Around that time, a weather station on Craig Key, Florida, observed a barometric pressure of 892 mbar (26.3 inHg), the lowest in relation to the storm.[3] About two hours later, the hurricane made landfall on Long Key at the same intensity. The storm made its final landfall on the sparsely populated Apalachee coast near Cedar Key on September 4 as a Category 2 hurricane. Turning northeast, the system weakened to a tropical storm over Georgia on September 5, but re-intensified into a hurricane on September 6 shortly after emerging into the Atlantic offshore Virginia. The storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone later that day,[7] but persisted until being absorbed by another extratropical cyclone offshore southern Greenland on September 10.[3]

In the Bahamas, the press stated that no damage occurred, though one report indicated that the storm caused some damage in extreme southern Andros Island.[3] With a minimum pressure of 892 mbar (26.3 inHg) upon landfall in the Florida Keys,[7] the hurricane became the most intense tropical cyclone to ever strike the United States or any landmass in the Atlantic basin.[14] The storm remained the most intense tropical cyclone in the Atlantic basin until Hurricane Gilbert in 1988 and later Hurricane Wilma in 2005.[15] The Labor Day hurricane also remains one of only four storms to strike the United States at Category 5 intensity, the others being Camille in 1969, Andrew in 1992, and Michael in 2018.[16] The Florida Climatological Data report notes that islands in the vicinity of the storm's landfall location "undoubtedly" experienced sustained winds between 150 and 200 mph (240 and 320 km/h) and with gusts "probably exceeding" 200 mph (320 km/h). Additionally, tides reached about 30 ft (9.1 m) above mean water level,[3] while a storm surge of 18 to 20 ft (5.5 to 6.1 m) lashed the Upper Keys.[17] A train intending to evacuate people to safety arrived too late, with storm surge preventing the train from advancing past Islamorada and instead washing it off the tracks except for the locomotive and tender. The hurricane caused near total destruction of all buildings, bridges, roads, and viaducts between Tavernier and Key Vaca, including portions of the Florida East Coast Railway in the Upper Keys.[18] Also heavily impacted were three Federal Emergency Relief Administration camps of World War I veterans. By March 1, 1936, officials had confirmed 485 deaths in the Florida Keys, with 257 veterans and 228 civilians killed.[19] Along Florida's gulf coast, the hurricane impacted Cedar Key particularly severely. Nearly all roofs experienced at least minor damage, many of which were blown off, while winds also downed many trees and power lines. The cyclone also severely damaged docks and fishing vessels. Three deaths occurred in the town.[3] Rains and winds damaged some crops and properties in Georgia and the Carolinas. In Virginia, one tornado in Norfolk caused about $22,000 in property damage while a second near Farmville resulted in about $55,000 in damage and two deaths. Further, flooding along the James Rivers inflicted damage around $1.65 million.[3] Overall, the hurricane caused approximately $100 million in damage.[20]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 30 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed in the northwestern Caribbean on August 30. The system moved westward and soon made landfall in the Yucatán Peninsula near Playa del Carmen.[7] After emerging into the Bay of Campeche on the following day, the cyclone intensified into a tropical storm. By early on September 1, the system peaked with sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). Around 18:00 UTC that day, the storm made landfall in the Mexican state of Veracruz to the southeast of the city of Veracruz.[7] After moving inland, the storm quickly weakened to a tropical depression early on September 2, before dissipating several hours later.[7] Authorities closed the Port of Veracruz.[21] A weather station in the city of Veracruz recorded sustained winds up to 67 mph (108 km/h).[3] Heavy rains generated by the system washed out train tracks, delaying railroad traffic.[21]

Hurricane Five

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 23 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) < 945 mbar (hPa) |

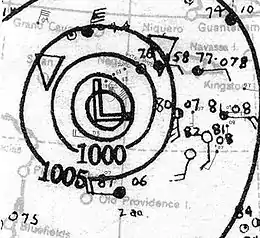

The Cuba Hurricane of 1935

The origin of this hurricane is uncertain, though it is believed to have coalesced into a tropical depression over the central Caribbean Sea on September 23.[22] The disturbance gradually organized as it moved to the west, and strengthened to tropical storm intensity less than a day after formation and further to a hurricane by September 25. The cyclone subsequently curved northward from its initial westward motion. On September 27, the storm reached major hurricane intensity before making landfall near Cienfuegos, Cuba, as a Category 3 hurricane the next day.[7][22] After passing the island, the system reintensified and peaked with a minimum barometric pressure below 945 mbar (hPa; 27.91 inHg)[nb 3] and maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (220 km/h), making it a Category 4 hurricane. At the same time, the tropical cyclone passed over the Bahamian island of Bimini before moving out to sea. As it progressed northeastward, the hurricane gradually weakened before transitioning into an extratropical storm on October 2. The extratropical remnants traversed Newfoundland before dissipating later that day.[7][22]

The hurricane caused widespread destruction from destruction from the Greater Antilles to Atlantic Canada.[23] In Jamaica, the storm's strong winds and heavy rain destroyed roughly 3 percent of the island's banana production and damaged road networks.[24] Damage on the island country totaled to $2.7 million and two people died.[25] In Cayman Brac, strong winds damaged infrastructure and crops, though no fatalities resulted.[23] Most of the cyclone's deaths occurred in Cuba, where the storm made its first landfall. The hurricane's effects left a 100 mi (160 km) wide swath of damage across the country.[26] A large storm surge destroyed low-lying coastal towns, particularly in Cienfuegos where numerous homes were destroyed and 17 people died.[27][28] Throughout the nation, the hurricane wrought $12 million in damage and killed 35 people.[23] As it crossed Cuba, widespread evacuation procedures occurred in southern areas of Florida, heightened due to the effects of a disastrous hurricane which struck less than a month prior.[29][30] However, damage there was only of moderate severity.[23] Passing directly over Bimini in The Bahamas, a large storm surge destroyed nearly half of the island; 14 people were killed here.[22] Farther north, the storm had slight impacts in Bermuda and Atlantic Canada, though a person drowned off of Halifax, Nova Scotia, due to rough seas.[31]

Hurricane Six

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 18 – October 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min) 988 mbar (hPa) |

A broad low-pressure area organized into a tropical depression over the southwestern Caribbean around 12:00 UTC on October 18.[7][3] Initially moving eastward, the depression intensified into a tropical storm roughly 24 hours later. The cyclone then began to curve north-northeastward and move very slowly. Around 13:00 UTC on October 21, the system made landfall in Jamaica near the Morant Point Lighthouse with winds of 60 mph (100 km/h). The storm reached hurricane intensity early on October 22 and made landfall near Santiago de Cuba later that day with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h). Although the storm curved southwestward and re-entered the Caribbean, land interaction with Cuba weakened it to a tropical storm early on October 23.[7] The storm re-intensified into a hurricane about eight hours later.[7] On October 26, it made landfall in Honduras near Cabo Gracias a Dios as a Category 1 hurricane. The cyclone maintained intensity after moving inland before weakening to a tropical storm on October 26, eventually weakening to a tropical depression on October 27 over interior Central America. The system dissipated shortly thereafter.[7]

Flooding and landslides in Jamaica damaged crops, property, and infrastructure; fruit growers alone suffered about $2.5 million in losses.[32] Just offshore, an unidentified vessel went down with her entire crew in the hostile conditions.[33] Strong winds lashed coastal sections of Cuba, particularly in and around Santiago de Cuba. There, the hurricane demolished 100 homes and filled streets with debris.[34] A total of four people died in the country.[3] In Haiti, the storm did most damage along the Tiburon Peninsula of southwestern Haiti, especially in Jacmel and Jérémie.[35] Catastrophic river flooding left roughly 2,000 people dead,[33] razed hundreds of native houses, and destroyed crops and livestock.[35] Entire swaths of countryside were isolated for days, delaying both reconnaissance and relief efforts.[36] The hurricane later unleashed devastating floods in Central America, chiefly in Honduras.[33] Reported at the time to be the worst flood in the nation's history, the disaster decimated banana plantations and communities after rivers flowed up to 50 ft (15 m) above normal.[37] Torrents of floodwaters trapped hundreds of citizens in trees, on rooftops, and on remote high ground, requiring emergency rescue.[38] The storm left thousands homeless and around 150 dead in the country,[33] while monetary damage totaled $12 million.[39] Flooding and strong winds also impacted northeastern Nicaragua, though damage was much less widespread.[33]

Hurricane Seven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 30 – November 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 964 mbar (hPa) |

The Yankee Hurricane of 1935 or The Miami Hurricane of 1935

A tropical storm of extratropical origins formed about 220 mi (355 km) east of Bermuda around 06:00 UTC on October 30.[40][7] The storm steadily intensified and moved west-northwestward, passing about 55 mi (90 km) north of Bermuda early on October 31. After reaching hurricane intensity around 12:00 UTC on the next day, the cyclone curved west-southwestward. The system then turned south-southwestward by early on November 3, around the time that it reached Category 2 strength. Peaking with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 964 mbar (28.5 inHg) shortly thereafter, the storm curved southwestward later that day while approaching the Bahamas. Just after 00:00 UTC on November 4, the hurricane struck North Abaco at the same intensity. The cyclone then continued west-southwestward and made landfall in Miami-Dade County, Florida, near present-day Bal Harbour around 18:00 UTC on November 4 with winds of 100 mph (155 km/h). The storm emerged into the Gulf of Mexico early the following day and weakened to a tropical storm around 00:00 UTC on November 6 while beginning to curve west-northwestward. Thereafter, the system decelerated and curved westward late on November 7, at which time it weakened to a tropical depression. By 12:00 UTC on November 8, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone about 140 mi (230 km) west of St. Petersburg, Florida, and dissipated several hours later.[7]

While the storm passed north of Bermuda on October 31, a weather station recorded sustained winds of 35 mph (56 km/h).[3] Hurricane-force winds lashed the Abaco Islands for approximately 1-3 hours, while Grand Bahama observed sustained winds of 60 mph (97 km/h). On the former, the storm sank five sponging vessels and caused 14 deaths.[40] The storm is known as the Yankee hurricane in Florida due to its unusual approach toward Florida from the north and its arrival late in the season.[41] In Florida, storm surge and abnormally high tides flooded and eroded portions of Miami Beach, including about 10 ft (3.0 m) of the causeway linking the city to Miami.[40] However, little structural damage occurred except to buildings with defect roofs.[42] In Hialeah, considered the worst hit city in the Miami area, approximately 230 homes suffered complete destruction, while many others sustained damage. Among the others buildings severely damaged or destroyed in the city included two churches, a building occupied by two businesses, and a warehouse.[43] The storm uprooted 75 percent of avocado trees and 80 percent of citrus trees, while floodwaters inundated about 95 percent of potatoes in Miami-Dade County.[42] In Broward County, the town of Dania Beach appeared to suffer the worst damage in the county, with approximately 90 percent of buildings damaged to some degree in the former.[44] Throughout the county, the hurricane damaged at least 40 homes beyond repairs, while over 350 homes suffered minor damages requiring repairs.[42] A total of 5 deaths were reported, along with injuries to 115 people. The hurricane caused approximately $5.5 million in damage in Florida, $4.5 million of which was incurred to properties.[40]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 3 – November 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) |

Based on historical weather maps, a weak trough developed into a tropical depression about 215 mi (345 km) northeast of Bermuda around 00:00 UTC on November 3.[3][7] The cyclone initially moved northeastward and reached tropical storm intensity around 18:00 UTC.[7] On November 4, the system attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg), the latter being observed by a ship.[3] The storm curved southeastward late on November 4 and then southwestward about 24 hours later. Late on November 6, the system turned to the west. On the following day as the cyclone began turning south-southwestward,[7] a weather station on Bermuda observed sustained winds of 40 mph (64 km/h).[3] The storm weakened to a tropical depression early on November 9 and began to execute a cyclonic loop. Around 12:00 UTC on November 10, it re-intensified into a tropical storm. The storm completed its cyclonic loop by November 12 and resumed moving south-southwestward. Around 06:00 UTC on November 13, the cyclone fell below tropical storm intensity again and dissipated early on November 14 while located about 300 mi (485 km) south-southeast of Bermuda.[7]

Other systems

In addition to the eight gale-force systems identified within HURDAT, two other cyclones were classified as tropical depressions. The first of these developed over the northern Gulf of Mexico on August 23. On this day, a ship observed sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h)—the highest in relation to the system. The lowest observed pressure of 1008 mbar (hPa; 29.77 inHg) was recorded on August 25. Researchers at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) noted that the system may have become a weak tropical storm, but a lack of concrete evidence prevented classification as such. Remaining nearly stationary for four days, the depression finally moved northeast on August 27 and made landfall over the Florida Panhandle. The system weakened once onshore and dissipated over Georgia on August 29. The second depression was identified near the Cape Verde Islands on October 2. A nearly stationary system, the depression lingered for three days before diminishing. Ships on October 2 reported sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a pressure of 1006 mbar (hPa; 29.71 inHg). The depression may have been a tropical storm, but this could not be conclusively assessed.[45]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that have formed during the 1935 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their names, duration, peak strength, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1935 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 15–18 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1003 | Hispaniola | Minimal | None | |||

| Two | August 16–25 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | < 955 | Lesser Antilles, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | Unknown | 50 | |||

| Depression | August 23–29 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1008 | Southeastern United States | None | None | |||

| "Labor Day" | August 29 – September 6 | Category 5 hurricane | 185 (295) | 892 | Bahamas, Southeastern United States (particularly the Florida Keys), Northeastern United States | $100 million | 490 | |||

| Four | August 30 – September 2 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1001 | Mexico | Minimal | None | |||

| Five | September 23 – October 2 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | < 945 | Jamaica, Cuba, Florida, Bahamas, Bermuda, Newfoundland | $14.5 million | 52 | |||

| Depression | October 2–5 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Six | October 18–27 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 988 | Jamaica, Cuba, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua | $16 million | 2,150 | |||

| Seven | October 30 – November 8 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 964 | Bahamas, Florida | $5.5 million | 19 | |||

| Eight | November 3–14 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1001 | Bermuda | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 10 systems | May 15 – November 14 | 185 (295) | 892 | >$126 million | 2,761 | |||||

Notes

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[2]

- All damage figures are in 1935 USD, unless otherwise noted

- A pressure of 945 mbar (hPa; 27.91 inHg) was observed on Bimini island in the Bahamas; however, this value was not measured in the hurricane's eye and indicates the storm was even more intense.[22]

References

- "Uncle Sam Closes Hurricane Warning System Over South". The Palm Beach Post. Associated Press. November 16, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- "Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season. Climate Prediction Center (Report). College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 6, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- Christopher W. Landsea (2019). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- "Worst Gale In 36 Years Lashes Newfoundland; 40 Persons Are Missing". The News-Palladium. Associated Press. August 28, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved November 27, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1935 – [Hurricane One]". Environment Canada. Canadian Hurricane Centre. November 18, 2009. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "NFLD. Gale Toll Elevated To 50 After Checkup". The Winnipeg Tribune. Canadian Press Cable. August 29, 1935. p. 3. Retrieved November 27, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Patrol Beaches After Gale To Locate Bodies". Oshkosh Daily Northwestern. Associated Press. August 29, 1935. p. 10. Retrieved March 14, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Lashes Coast; Death Toll Unknown". Miami Daily News-Record. Associated Press. August 26, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved November 27, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Crews Of 4 Schooners Feared Lost As Gale Hits Newfoundland". The Index-Journal. Associated Press. August 27, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved November 27, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jeff Masters (August 30, 2019). "How Might Cat 4 Dorian Compare to the Great Florida Keys Labor Day Hurricane of 1935?". Weather Underground. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Hurricanes in History". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Hurricane Camille - August 17, 1969 (Report). National Weather Service Mobile, Alabama. August 2019. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Craig Setzer (September 8, 2017). "Irma Draws Comparison To Great Labor Day Hurricane Of 1935". WFOR-TV. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- W.F. McDonald (September 1, 1935). "The Hurricane of August 31 to September 6, 1935" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 63 (9): 269. Bibcode:1935MWRv...63..269M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1935)63<269:THOATS>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2017. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Florida Hurricane Disaster: Hearings Before the Committee On World War Veterans' Legislation, House of Representatives, Seventy-fourth Congress, Second Session (Report). World War Veterans' Legislation. 1936. p. 332. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "A look back: Five of Florida's worst hurricanes". New Haven Register. August 30, 2019. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- "Small Boats Feared Lost in Gulf of Mexico Storm". The Knoxville Journal. Associated Press. September 3, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved March 6, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Christopher Landsea; et al. (December 2012). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT: 1935 Storm Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- W.F. McDonald (September 1, 1935). "West Indian Hurricane, September 23 To October 2, 1935" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 63 (9): 271–272. Bibcode:1935MWRv...63..271M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1935)63<271:WIHSTO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Banana Crop Damaged". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. September 27, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "30 Dead, 250 Hurt In Hurricane". The Vancouver Sun. Associated Press. September 28, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- "1,000 Houses Gone; High Seas Destroy Town". The Miami News. Associated Press. September 28, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Wall of Water 15 Feet Deep Adds To Havoc". The Miami News. Associated Press. September 30, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Wall of Water 15 Feet Deep Adds To Havoc". The Miami News. Associated Press. September 30, 1935. p. 13. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1,000 Houses Gone; High Seas Destroy Town". The Miami News. Associated Press. September 28, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Haas, Lawrence S. (September 28, 1935). "300 Cubans Injured". Berkeley Daily Gazette. United Press. p. 1. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "Relief Rushed". The Deseret News. Associated Press. September 28, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "Storm Leaves 37 Dead And 300 Hurt In Cuba". The Meriden Daily Journal. Associated Press. September 30, 1935. p. 8. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "Storm Warnings Hoisted in Florida; Hurricane Threat". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. September 28, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "Keys Evacuated As Danger Becomes Known". The Miami News. September 28, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1935 – [Hurricane Four]". Environment Canada. Canadian Hurricane Centre. November 18, 2009. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "Cuba Clearing Storm Debris". The Racine Journal-Times. Associated Press. October 23, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- W.F. McDonald (October 1935). "The Caribbean Hurricane of October 19–26, 1935" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 63 (10): 294–295. Bibcode:1935MWRv...63..294M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1935)63<294:TCHOO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 29, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- "Hurricane on Way Out to Sea". The Olean Times-Herald. October 23, 1935. p. 10. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Death Toll May Reach 1,000 In Haiti Hurricane-Flood; 200 Bodies Are Recovered". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Associated Press. October 27, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "1500 Feared Dead in Haiti Flood". The Salt Lake Tribune. United Press International. October 27, 1935. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Deaths in Honduras". Montana Butte Standard. Associated Press. October 28, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Many Trapped by High Water in Honduras". The Daily Mail. Associated Press. October 29, 1935. p. 12. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Edward W. Pickard (November 8, 1935). "News Review of Current Events the World Over". The Bode Bugle. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- Willis E. Hurd (November 1935). "The Atlantic-Gulf of Mexico Hurricane of October 30 to November 8, 1935" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: American Meteorological Society. 63 (11): 316–318. Bibcode:1935MWRv...63..316H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1935)63<316:TAOMHO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Marjory Stoneman Douglas (1958). "The Florida Keys, 1935". Rinehart and Company. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "Work of Repairing is Moving Forward". Miami Herald. November 6, 1935. p. 4-A. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Work of Repairing is Moving Forward". Miami Herald. November 6, 1935. p. 5-A. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Repair Work Begun in Broward County". Miami Herald. November 6, 1935. p. 5-A. Retrieved March 7, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Christopher Landsea; et al. (December 2012). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT: 1935 Storm Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1935 Atlantic hurricane season. |