1961 Atlantic hurricane season

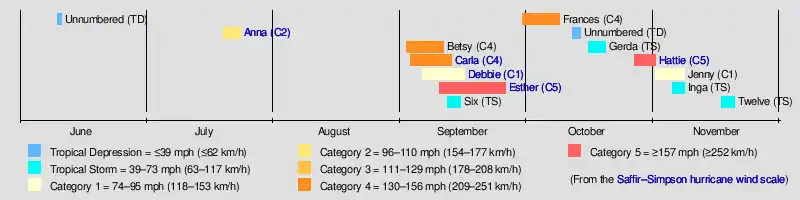

The 1961 Atlantic hurricane season was an extremely-active Atlantic hurricane season, with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) total of 205. The season, however, was only a moderately above average one in terms of named storms. The season did feature 8 hurricanes and a well above average number of 5 major hurricanes (It was once a record-tying 7 major hurricanes before the reanalysis project). The season featured a record-tying five category 4 hurricanes, tying 1999, 2005, and 2020. Two category 5 hurricanes were seen in 1961, making it one of only seven Atlantic hurricane seasons to feature more than one category 5 hurricane in one season. The season started on June 15, and ended on November 15. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The first system, Hurricane Anna, developed in the eastern Caribbean Sea near the Windward Islands on July 20. It brought minor damage to the islands, as well as wind and flood impacts to Central America after striking Belize as a hurricane.[nb 1] Anna caused one death and about $300,000 (1961 USD)[nb 2] in damage. Activity went dormant for nearly a month and a half, until Hurricane Betsy developed on September 2. Betsy peaked as a Category 4 hurricane, but remained at sea and caused no impact.

| 1961 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | July 20, 1961 |

| Last system dissipated | November 20, 1961 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Hattie |

| • Maximum winds | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 914 mbar (hPa; 26.99 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 14 |

| Total storms | 12 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 5 |

| Total fatalities | 455 |

| Total damage | $442.34 million (1961 USD) |

| Related articles | |

One of the most significant storms of the season was Hurricane Carla, which peaked as a Category 4 hurricane, before weakening slightly and striking Texas. Carla caused 43 deaths and approximately $325.74 million in damage. Hurricane Debbie was a Category 3 storm that existed in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Early in its duration, unsettled weather from Debbie in Cape Verde resulted in a plane crash that killed 60 people. Debbie then brushed Ireland as either a Category 1 hurricane or shortly after becoming extratropical. The next storm, Hurricane Esther, threatened to strike New England as a major hurricane, but rapidly weakened and made landfall in Massachusetts as only a tropical storm. Impact was generally minor, with about $6 million in damage and seven deaths, all of which from a United States Navy plane crash. An unnamed tropical storm and Hurricane Frances caused minimal impact on land. In mid-October, Tropical Storm Gerda brought flooding to Jamaica and eastern Cuba, resulting in twelve deaths.

Another significant storm was Hurricane Hattie, a late-season Category 5 hurricane that struck Belize. Hattie caused 319 confirmed fatalities and about $60.3 million in damage. Destruction was so severe in Belize that the government had to relocate inland to a new city, Belmopan. In early November, the depression that would later strengthen into Hurricane Jenny brought light rainfall to Puerto Rico. The final storm, Tropical Storm Inga, dissipated on November 8, after causing no impact on land. On September 11, three hurricanes existed simultaneously – Betsy, Carla, and Debbie – the most on a single day in the Atlantic basin since 1893 and until 1998. Collectively, the storms of the 1961 Atlantic hurricane season caused about $391 million in damage and at least 348 fatalities.

Season summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 15.[1] It was an above average season in which eleven tropical storms formed; this was above the 1950–2000 average of 9.6 named storms.[2] Eight of these reached hurricane status, also above of the 1950–2000 average of 5.9.[3][2] Furthermore, five storms reached major hurricane status. It was originally believed that the season had seven major hurricanes, though later analysis resulted in a downgrade of two storms.[4] Of the five major hurricanes, two became Category 5 hurricanes. Four hurricanes and two tropical storms made landfall during the season,[3] causing 348 deaths and $391.6 million in damage.[5] Hurricane Debbie also caused damage and deaths, despite remaining offshore and then after becoming extratropical.[6][7]

Although the season officially began on June 15,[1] the first tropical cyclone, Hurricane Anna, did not develop until July 20. After Anna dissipated on July 24, there were no other systems in July or the month of August. Tropical cyclogenesis did not resume until Hurricane Betsy developed on September 2. During the next four days, two other tropical cyclones formed – Carla and Debbie. On September 11, the three storms – Betsy, Carla, and Debbie – existed simultaneously as hurricanes,[3] the most in a single day since 1893 and until 1998.[8] Esther, which developed on September 10, did not reach hurricane status until September 12. Later that day, a tropical storm that went unnamed formed over the Bahamas and moved across the East Coast of the United States for its brief duration.[3][9]

After Debbie became extratropical on September 26, another tropical cyclone developed four days later, Hurricane Frances. Thereafter, tropical cyclogenesis slowed in October, which featured only two systems, Gerda and Hattie. The latter was the strongest tropical cyclone of the season, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 165 mph (266 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 914 mbar (27.0 inHg). After weakening slightly, Hattie struck Belize on October 31, before dissipating on November 1. Later that day, Hurricane Jenny developed near Antigua. Jenny remained weak for much of its duration and became extratropical on November 8. The final system, Tropical Storm Inga, formed in the Gulf of Mexico on November 5. Three days later, Inga dissipated,[3] one week before the season officially ended.[10]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 205, one of the highest values recorded.[4] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength. Subtropical cyclones are excluded from the total.[11]

Systems

Hurricane Anna

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 20 – July 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min) 976 mbar (hPa) |

An easterly wave developed into Tropical Storm Anna in the vicinity of the Windward Islands on July 20.[12][3] The storm moved westward across the Caribbean Sea. Favorable environmental conditions allowed Anna to reach hurricane intensity late on July 20. Early on the following day, the storm strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane. Intensification continued, and later on July 21, Anna became a major hurricane. After attaining peak intensity on July 22, the hurricane slightly weakened while brushing the northern coast of Honduras. Further weakening occurred; when Anna made landfall in Belize on July 24, winds decreased to 80 mph (130 km/h). Anna rapidly weakened over land and dissipated later that day.[3]

As a developing tropical cyclone over the Windward Islands, Anna produced strong winds over Grenada, though damage was limited to some crops, trees, and telephone poles.[13] Other islands experienced gusty winds, but no damage. Passing just north of Venezuela, the hurricane produced strong winds over the country, peaking as high as 70 mph (110 km/h).[14] Strong winds caused widespread damage in northern Honduras. Throughout the country, at least 36 homes were destroyed and 228 were damaged.[15] Severe damage in the Gracias a Dios Department left hundreds of people homeless.[16] Additionally, high winds toppled approximately 10,000 coconut trees.[15] Overall, Anna caused one fatality and $300,000 in damage, primarily in Central America.[12][16]

Hurricane Betsy

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 2 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) 945 mbar (hPa) |

In early September, a tropical wave was noted in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ).[12][17] On September 2, the disturbance was analyzed to have attained tropical storm strength, after nearby ship reports indicated strong winds associated with anomalously low barometric pressures.[12] Moving steadily northwestward, Betsy gradually intensified under favorable conditions. By 12:00 UTC the following day, the storm had strengthened to Category 1 hurricane intensity.[3] Shortly after, a trough situated along 50°W steered Betsy to a more northerly course. Another low-pressure area later formed in the trough, perturbing the ridge to the north of Betsy for much of its initial stages, causing the hurricane's central pressure to rise,[12] despite an increase in sustained winds.[3] However, on September 5, a shortwave forced the low northeastward, allowing for Betsy to strengthen further.[12]

Later on September 5, Betsy attained Category 4 hurricane strength, before subsequently reaching peak intensity the following day with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) and a central pressure of 945 mbar (hPa; 27.91 inHg), based on reconnaissance flights into the system.[3] However, as a result of missing the short wave itself, the hurricane later weakened and fell to Category 3 intensity while located about 440 miles (710 km) east-northeast of Bermuda. Betsy weakened further to Category 2 hurricane before becoming nearly stationary beginning on September 6,[12] where it maintained its intensity for several days.[3] A separate, minor trough was later able to move the system northeastwards on September 9.[12] Moving into highly latitudes, Betsy began to weaken, degenerating back to Category 1 hurricane intensity on September 11 before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone the following day. The extratropical remnants continued northeastward and weakened, before dissipating west of Ireland early on September 12.[3] Due to its distance from any landmasses, no damage was associated with the tropical cyclone.[17]

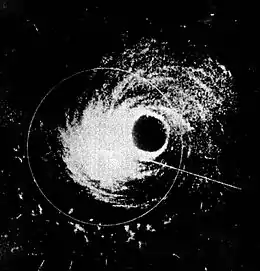

Hurricane Carla

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 3 – September 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min) 927 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression developed from an area of squally weather embedded within the ITCZ in the southwestern Caribbean Sea on September 3.[18] Initially a tropical depression, it strengthened slowly while heading northwestward, and by September 5, the system was upgraded to Tropical Storm Carla.[3][19] About 24 hours later, Carla was upgraded to a hurricane.[3][20] Shortly thereafter, the storm curved northward while approaching the Yucatán Channel. Late on September 7, Carla entered the Gulf of Mexico while passing just northeast of the Yucatán Peninsula. By early on the following day, the storm became a major hurricane. Resuming its northwestward course, Carla continued intensification and on September 11, it peaked as a Category 4 hurricane. Carla made landfall near Port O'Connor, Texas with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h). It weakened quickly inland and was reduced to a tropical storm on September 12. Heading generally northward, Carla transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 13, while centered over southern Oklahoma. However, the remnants continued generally northeastward and entered Canada on September 14, before dissipating near Cape Chidley early on September 16.[3]

While crossing the Yucatán Channel, the outer bands of Carla brought gusty winds and severe local flooding in western Cuba and the Yucatán Peninsula, though no damage or fatalities were reported.[12][21] Although initially considered a significant threat to Florida,[22] the storm brought only light winds and small amounts of precipitation, reaching no more than 3.15 in (80 mm).[21] In Texas, wind gusts as high as 170 mph (270 km/h) were observed in Port Lavaca. Additionally, several tornadoes spawned in the state caused notable impacts, with the most destructive tornado striking Gavelston, Texas at F4 intensity, resulting in 200 buildings being severely damaged, of which 60-75 were destroyed, eight deaths and 200 injuries.[23] Throughout the state, Carla destroyed 1,915 homes, 568 farm buildings, and 415 other buildings. Additionally, 50,723 homes, 5,620 farm buildings, and 10,487 other buildings suffered damage. There were 34 fatalities and at least $300 million in losses in Texas alone. Several tornadoes also touched down in Louisiana, causing the destruction of 140 homes and 11 farms and other buildings, and major damage to 231 additional homes and 11 farm and other buildings. Minor to moderate damage was also reported to 748 homes and 75 farm and other buildings.[24] Six deaths and $25 million in losses in Louisiana were attributed to Carla.[25] Heavy rainfall occurred in several other states, especially in Kansas,[26] where flash flooding severely damaged crops and drowned five people.[27] Overall, Carla resulted in $325.74 million in losses and 46 fatalities.[25][27][28] In Canada, the remnants of Carla brought strong winds to Ontario and New Brunswick, though impact was primarily limited to power outages and falling trees and branches.[29]

Hurricane Debbie

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 6 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 975 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical disturbance was first identified in late August over Central Africa.[30] It was estimated to have become a tropical storm on September 6. Later that day, Debbie passed through the southern Cape Verde Islands as a strong tropical storm or minimal hurricane,[3] resulting in a plane crash that killed 60 people.[7] Once clear of the islands, data on the storm became sparse, and the status of Debbie was uncertain over the following several days as it tracked west-northwestward and later northward. It was not until a commercial airliner intercepted the storm on September 10 that its location was certain.[31] The following day, Debbie intensified and reached its peak intensity as a strong Category 1 hurricane with winds of 90 mph (140 km/h). The hurricane gradually slowed its forward motion and weakened.[3] By September 13, Debbie's motion became influenced by the westerlies, causing the system to accelerate east-northeastward.[31]

The system passed over the western Azores as a minimal hurricane on September 15.[3] At this point, there is uncertainty as to the structure of Debbie, whether it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone or maintained identity as a tropical system. Regardless, the system deepened as it neared the British Isles,[3][31] skirting the coast of Western Ireland on September 16 after becoming post-tropical.[3] In Ireland, Debbie brought record winds to much of the island, with a peak gust of 114 mph (183 km/h) measured just offshore.[32] Widespread wind damage and disruption occurred, downing tens of thousands of trees and power lines.[33][34] Countless structures sustained varying degrees of damage, with many smaller buildings destroyed.[35] Agriculture experienced extensive losses to barley, corn and wheat crops.[36] Throughout Ireland, Debbie killed 18 people, with 12 in the Ireland and six in Northern Ireland.[6] It caused $40–50 million in damage in the Republic and at least £1.5 million (US$4 million) in Northern Ireland. The storm also battered parts of Great Britain with winds in excess of 100 mph (160 km/h).[12]

Hurricane Esther

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 10 – September 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min) 919 mbar (hPa) |

On September 10, Television Infrared Observation Satellite (TIROS) III observed an area of disturbed weather well southwest of the Cape Verde Islands.[12] Later that day, a tropical depression developed about 540 miles (870 km) west-southwest of the southernmost Cape Verde Islands. Moving northwestward, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Esther on September 11, before reaching hurricane intensity on the following day. Early on September 13, Esther curved westward and deepened into a major hurricane. The storm remained a Category 3 hurricane for about four days and gradually moved in west-northwestward direction. Late on September 17, Esther strengthened into a Category 4 hurricane and peaked as a Category 5 hurricane with sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) on September 18.[3]

The storm curved north-northeastward on September 19, while offshore North Carolina. Esther began to weaken while approaching New England and fell to Category 2 intensity on September 21. Early on September 22, the storm turned eastward and gradually weakened to a tropical storm the next day. It then executed a large cyclonic loop, until curving northward on September 25. Early on the following day, Esther struck Cape Cod, hours before emerging into the Gulf of Maine. Later on September 26, the storm made landfall in southeastern Maine, before weakening to a tropical depression and becoming extratropical over southeastern Quebec. The remnants persisted for about 12 hours, before dissipating early on September 27.[3] Between North Carolina and New Jersey effects were primarily limited to strong winds and minor beach erosion and coastal flooding due to storm surge.[37] In New York, strong winds led to severe crop losses and over 300,000 power outages. High tides caused coastal flooding and damage a number of pleasure boats. Similar impact was reported in Massachusetts. Additionally, some areas observed more than 8 inches (200 mm) of rainfall, flooding basements, low-lying roads, and underpasses.[27] Overall, damage was minor, totaling about $6 million.[12] There were also seven deaths reported when United States Navy P5M aircraft crashed about 120 miles (190 km) north of Bermuda.[38]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

.JPG.webp)  | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 996 mbar (hPa) |

TIROS III imagery indicated a vortex east of the Bahamas between September 9 and September 12.[9] A tropical depression formed at 12:00 UTC on September 12, after TIROS revealed a surface circulation. The depression tracked northward and intensified into a tropical storm while located offshore North Carolina. Early on September 14, it made landfall in the state near Wilmington, North Carolina with winds of 40 mph (64 km/h). The storm curved northeastward and accelerated across the Mid-Atlantic, New England, and New Brunswick. The tropical storm reached the highest forward-motion for any cyclone in the Atlantic hurricane database, with a maximum speed of 112 km/hr (61 kt or 70 mph) as it moved over Maine and New Brunswick.[39][3]

Impact from the storm was generally minor. In Savannah, Georgia, the storm produced an F2 tornado that blew the roof off of a lumber company building. In North Carolina, 3.12 inches (79 mm) of precipitation fell at Williamston.[40] Strong winds lashed Rhode Island, with winds as high as 70 mph (110 km/h) in Point Judith. About 29,000 homes were left without electricity, while 1,200 lost telephone service. Hundreds of small crafts and a few ferries and barges were swamped or sank. Hurricane-force wind gusts in Massachusetts felled trees, electrical wires, and TV antennas. Some roads in the southeastern portion of the state were blocked by fallen trees. Similar impact was reported in Maine, where an F2 tornado/waterspout tracked 19.1 miles (30.7 km) from Beals through Roque Bluffs before dissipating in Dog Town just east of East Machias. Power lines were considerably damaged and numerous trees were knocked down, including two incidents where trees fell on and damaged homes. The tornado caused one injury when a man was hit by a flying wooden plank.[27]

Hurricane Frances

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 30 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min) 948 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave organized into a tropical depression on September 30, east of the northern Lesser Antilles.[41][3] Six hours later, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Frances. Heading westward, it crossed through the Leeward Islands and entered the Caribbean Sea on October 1.[3] Thereafter, the lack of divergence at high levels prevented significant strengthening for a few days.[41] While situated south of Puerto Rico on October 2, Frances curved northwestward.[3] The storm brought heavy rainfall to Puerto Rico, peaking at 10.15 inches (258 mm) in the Indiera Baja barrio of Maricao.[40] Considerable damage to roads and bridges occurred. However, due to swift evacuations of residents by the Civil Defense and American Red Cross, no fatalities were reported.[41]

Tracking to the northwest, Frances made landfall near Punta Cana, Dominican Republic early on October 3 with winds of 60 mph (97 km/h). No impact was reported on the island. Later on October 3, Frances emerged into the Atlantic Ocean just southeast of the Turks and Caicos Islands. Thereafter, the storm accelerated somewhat and resumed intensification, reaching hurricane status on October 4. Around that time, it curved northeastward and deepened further. Early on October 7, Frances attained its peak intensity with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 948 mbar (28.0 inHg).[3] The storm passed by Bermuda around that time, where it dropped 1.35 inches (34 mm) of precipitation.[40] Later on October 7, Frances re-curved to the north. Early on the following day, it turned northwestward and began to weaken, falling to minimal hurricane intensity around 06:00 UTC on October 9. Six hours later, Frances became extratropical over the Gulf of Maine. The remnants curved east-northeastward and struck Nova Scotia, before dissipating early on October 10.[3]

Tropical Storm Gerda

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 16 – October 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 988 mbar (hPa) |

A westward-moving tropical wave developed into a tropical depression on October 16, while located south of Jamaica.[12][3] Shortly thereafter, the depression made landfall in Clarendon Parish. It continued northward and made another landfall near Santa Cruz del Sur, Cuba on October 17.[3] The depression brought heavy rainfall to Jamaica and eastern Cuba.[12] In the former, flooding caused damage to roads and forced many to evacuate their homes in western Kingston. Five fatalities were reported in Jamaica.[42] Flooding in eastern Cuba resulted in seven deaths. After striking Cuba, the depression emerged into the Atlantic and then crossed the Bahamas.[12]

The depression accelerated to the north-northeast and finally began to strengthen. Late on October 19, the depression reached tropical storm intensity and was named Gerda, while located between Bermuda and the East Coast of the United States. The storm curved northeastward on October 20, while peaking with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h).[3] However, a Texas Tower offshore Massachusetts observed hurricane-force winds.[12] At 00:00 UTC on October 21, Gerda transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, while situated about 100 miles (160 km) east-southeast of Barrington, Nova Scotia.[3] Damage from the storm in New England was "about the same as that from a typical wintertime northeaster".[12] The remnants of Gerda moved northeastward and then to the east, before dissipating between Newfoundland and the Azores late on October 22.[3]

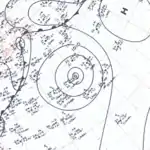

Hurricane Hattie

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 27 – November 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 mph (270 km/h) (1-min) 914 mbar (hPa) |

In late October, an area of low pressure persisted in the western Caribbean Sea for several days.[43] On October 27, a ship and the airport on San Andres Island reported a closed center of circulation associated with the low.[12] Thus, the system was classified as Tropical Storm Hattie starting on October 27. Moving towards the north and north-northeast, the storm quickly gained hurricane status and major hurricane status the following day. Hattie turned towards the west to the east of Jamaica, and strengthened into a Category 5 hurricane, with maximum sustained winds of 165 mph (270 km/h) before weakening to Category 4 status at landfall south of Belize City. Continuing southwest, the storm rapidly weakened over the mountainous terrain of Central America, dissipating on November 1.[3] It was originally thought that the remnants may have contributed to the development of Tropical Storm Simone in the eastern Pacific Ocean, however a 2019 reanalysis concluded that the remnants of Hattie instead became a Central American gyre.[44]

Hattie first affected regions in the southwestern Caribbean, producing hurricane-force winds and causing one death on San Andres Island.[12] It was initially forecast to continue north and strike Cuba, which prompted evacuations.[45] Little effects were reported as Hattie turned to the west, although rainfall reached 11.5 in (290 mm) on Grand Cayman.[43] The worst damage was in the country of Belize. The former capital, Belize City, was flooded by a powerful storm surge and high waves and affected by strong winds. The territory governor estimated 70% of the buildings in the city were damaged, which left over 10,000 people homeless.[46] The damage was severe enough that it prompted the government to relocate inland to a new city, Belmopan.[47] In the territory, Hattie left about $60 million in damage and caused 307 deaths.[12][48] The government estimated that Hattie was more damaging than a hurricane in 1931 that killed 2,000 people; the lower toll for Hattie was due to advance warning. Elsewhere in Central America, the hurricane killed 11 people in Guatemala and one in Honduras.[12]

Hurricane Jenny

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 1 – November 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 974 mbar (hPa) |

A surface trough of low pressure developed in the eastern Caribbean Sea on October 30. The trough split, with the northern portion spawning a tropical depression near Antigua at 12:00 UTC on November 1.[3][49] In the early stages of Jenny, light rainfall was observed in Puerto Rico, peaking at 4.97 inches (126 mm).[49] Moving northeastward ahead of an upper-level trough, the depression remained weak for over four days. On November 3, it curved eastward, before briefly turning to the southeast on November 4. The depression tracked in a circular path during the next 24 hours, moving northeastward, north-northwestward, and then west-northward. Finally, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Jenny early on November 6.[3]

Jenny intensified further and reached hurricane status at 12:00 UTC on November 6. Later that day, the United States Weather Bureau began advisories and described Jenny as having "characteristic of many storms in the sub-tropics late in the hurricane season."[50] Around 18:00 UTC on November 6, Jenny attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 974 mbar (28.8 inHg). Thereafter, the storm briefly decelerated and weakened, falling to tropical storm intensity around midday on November 7. Jenny curved northeastward and continued to weaken.[3] A reconnaissance flight into the system on November 8 indicated that the storm became extratropical about 895 miles (1,440 km) east of Bermuda.[3][50] The extratropical remnants continued to move northeastward and weakened, dissipating late on November 9.[3]

Tropical Storm Inga

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 4 – November 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) |

Early on November 4, the SS Navigator encountered a weather system in the Gulf of Mexico that produced northwesterly winds of 81 to 92 mph (130 to 148 km/h).[12] Reconnaissance aircraft data indicated that Tropical Storm Inga developed at 00:00 UTC on November 5, while located about 145 miles (233 km) northeast of Veracruz.[3][12] A strong high pressure system and a cold front entering the Gulf of Mexico from Texas caused the storm to move southward and then southeastward. Inga slowly strengthened and peaked as a 70 mph (110 km/h) tropical storm early on November 7. Thereafter, the storm became nearly stationary and began weakening.[12] By 12:00 UTC on November 8, Inga dissipated in the Bay of Campeche,[3] as reconnaissance aircraft found no closed circulation.[12]

Tropical Storm Twelve

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 17 – November 20 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) ≤ 992 mbar (hPa) |

A stationary front across the central Atlantic Ocean led to the development of a low pressure area by November 16, northeast of the Lesser Antilles. A day later, it is estimated that a tropical depression developed, although due to the system's large size, it was possible it was a subtropical cyclone. The depression moved northeastward and slowly intensified, based on observations from nearby ships. On November 19, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm. The storm strengthened to reach peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) on November 20. By that time, a cold front was approaching the storm, causing the storm to transition into an extratropical cyclone on November 21; later that day, the front absorbed the former tropical storm.[51]

Other storms

A report from Mexico indicates that a tropical depression formed off the west coasts of Tabasco and Coatzacoalcos. The depression significantly impacted the northern portions of Veracruz with heavy rainfall on June 30.[52] However, the Atlantic hurricane best track does not list this system as a tropical depression.[3]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1961.[53] Storms were named Frances, Hattie, Inga and Jenny for the first time in 1961. The names Carla and Hattie were later retired.[54] Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

|

Season effects

The following table lists all of the storms that have formed in the 1961 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s) (in parentheses), damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1961 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anna | July 20 – 24 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 976 | Windward Islands, Colombia, Venezuela, Central America, Jamaica | $300,000 | 1 | |||

| Betsy | September 2 – 11 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 945 | None | None | None | |||

| Carla | September 3 – 13 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 927 | Central America, Yucatán Peninsula, Central United States, Eastern Canada | $325.74 million | 43 | |||

| Debbie | September 6 – 16 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 975 | Cape Verde, Azores, Ireland, United Kingdom, Norway, Soviet Union | $50 million | 78 | |||

| Esther | September 10 – 26 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 919 | North Carolina, Virginia, New England, Mid-Atlantic, Atlantic Canada | $6 million | 0 (7) | |||

| Six | September 12 – 15 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 996 | The Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | Minimal | None | |||

| Frances | September 30 – October 9 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 948 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, Bermuda, Maine, Atlantic Canada | Unknown | None | |||

| Gerda | October 16 – 20 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 988 | Jamaica, Cuba, The Bahamas, New England, Atlantic Canada | Unknown | 7 | |||

| Hattie | October 27 – November 1 | Category 5 hurricane | 165 (270) | 914 | Central America (Belize) | $60.3 million | 319 | |||

| Jenny | November 1 – 10 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 974 | Puerto Rico, Leeward Islands | None | None | |||

| Inga | November 4 – 8 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 997 | Mexico | None | None | |||

| Twelve | November 17 – 20 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 992 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 12 systems | July 20 – November 20 | 165 (270) | 914 | $442.34 million | 448 (7) | |||||

See also

- 1961 Pacific hurricane season

- 1961 Pacific typhoon season

- 1961 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

Notes

- Prior to its independence in 1981, Belize was known as British Honduras

- All damage figures are in 1961 United States dollar, unless otherwise noted

References

- "Hurricane Season Here Today". Florence Morning News. 1961.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 8, 2006). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2007 (Report). Boulder, Colorado: Colorado State University. Archived from the original on December 18, 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- Gordon E. Dunn (March 1962). The Hurricane Season of 1961 (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- Luther Hodges (1961). Storm Data And Unusual Weather Phenomena: September 1961 (PDF). United States Department of Commerce (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 99–101, 103. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Luther Hodges. Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena: December 1961 (PDF). United States Department of Commerce (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 120. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- "Gale Killed Fifteen". Irish Independent. September 18, 1961. p. 3. – via Irish Newspaper Archives (subscription required)

- Exceptional Weather Events - "Hurricane Debbie" (PDF) (Report). Met Éireann. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Patrick J. Imhof (September 13, 2005). Rescue at Sea (PDF) (Report). Pensacola, Florida. pp. 4–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Floods Fatal To 5 Jamaicans". Savannah Morning News. Kingston, Jamaica. Associated Press. October 20, 1961. p. 5. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- "Belize Marked 45th Anniversary of Deadly Hurricane Hattie". Belize National Emergency Management Organization (NEMO) (Press release). NEMO Press Officer. November 2, 2006. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- "Gale Killed Fifteen". Irish Independent. September 18, 1961. p. 3. – via Irish Newspaper Archives (subscription required)

- Exceptional Weather Events - "Hurricane Debbie" (PDF) (Report). Met Éireann. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Christopher W. Landsea. Subject: E18) What was the largest number of hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean at the same time?. Hurricane Research Division (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Richard Fay (August 1962). Northbound Tropical Cyclone (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Hurricane "season" at end". United Press International. 1961.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- Gordon E. Dunn (March 1962). The Hurricane Season of 1961 (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved January 31, 2014.

- "Anna Should Miss Jamaica". The Daily Gleaner. 1961.

- Ralph L. Higgs (August 4, 1961). Report on Hurricane Anna – July 20, 1961. U.S. Weather Bureau Office San Juan, Puerto Rico (Report). San Juan, Puerto Rico: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- Etat; Gordon E. Dunn (August 4, 1961). Report on Hurricane Anna. U.S. Weather Bureau Office Miami, Florida (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. p. 11. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- "Miami Gets Pelted With Short Storms". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Hurricane Center. 1961. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- Hurricane Betsy, September 2-11, 1961 (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ECH (September 21, 1961). Carla Preliminary Report. United States Weather Bureau (Report). New Orleans, Louisiana: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 12. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ECH (September 21, 1961). Carla Preliminary Report. United States Weather Bureau (Report). New Orleans, Louisiana: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 13. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ECH (September 21, 1961). Carla Preliminary Report (GIF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). New Orleans, Louisiana: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 14. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- "Hurricane Whips Cuba; Winds Batter Key West". The Miami News. September 7, 1961. p. 72. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Conner (September 7, 1961). Hurricane Advisory Number 15 Carla. Weather Bureau Office New Orleans, Louisiana (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Robert Orton (September 16, 1961). Hurricane Carla in Texas September 8 to 13th, 1961. Weather Bureau Office Galveston, Texas (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 1. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- Robert Orton (September 18, 1961). List of known dead in Texas from Hurricane Carla as of September 18th. Weather Bureau Office Galveston, Texas (Report). National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Hurricane Carla: September 4–14, 1961 (A Preliminary Report). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 18, 1961. p. 2. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Midwest (Report). College Park, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Luther Hodges (1961). Storm Data And Unusual Weather Phenomena: September 1961 (PDF). United States Department of Commerce (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 99–101, 103. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- Luther Hodges. Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena: December 1961 (PDF). United States Department of Commerce (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 120. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- 1961-Carla (Report). Fredericton, New Brunswick: Environment Canada. November 5, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- C. O. Erickson (February 1963). An Incipient Hurricane Near The West African Coast (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 61–68. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Hurricane Debbie — September 7–15, 1961 Preliminary Report (PDF). National Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1961. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- "Repairing Hurricane Damage". Connacht Sentinel. September 19, 1961. p. 10. – via Irish Newspaper Archives (subscription required)

- "Storm Reports From The Areas". Anglo-Celt. September 23, 1961. p. 9. – via Irish Newspaper Archives (subscription required)

- "The Storm Made Much Work". Ulster Herald. September 23, 1961. p. 7. – via Irish Newspaper Archives (subscription required)

- J. G. Gruickshank; N. Stephens; L. J. Symons (January 1962). "Report of the Hurricane in Ireland on Saturday, 16 September, 1961". The Irish Naturalists' Journal. 14 (1): 4–12. JSTOR 25534822.

- "Crop Losses". Irish Farmers Journal. September 23, 1961. p. 1. – via Irish Newspaper Archives (subscription required)

- Hurricane Esther — September 12–26, 1961 Preliminary Report (PDF). National Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1961. p. 4. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Patrick J. Imhof (September 13, 2005). Rescue at Sea (PDF) (Report). Pensacola, Florida. pp. 4–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "What is the average forward speed of a hurricane?". Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Hurricane Frances, September 30 October 9, 1961 (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Floods Fatal To 5 Jamaicans". Savannah Morning News. Kingston, Jamaica. Associated Press. October 20, 1961. p. 5. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- Hurricane Esther — October 27–31, 1961 Preliminary Report (PDF). National Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1961. p. 4. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Sandy Delgado, Christopher Landsea, and Brenden Moses (2019). Reanalysis of the 1961–65 Atlantic hurricane seasons (PDF) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. pp. 80–90. Retrieved November 26, 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "'Cane Hattie Threatens Western Cuba, Florida". The Palm Beach Post. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 30, 1961. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Hattie's Toll is 62: Martial Law Declared". St. Petersburg Times. Belize City, British Honduras. United Press International. November 2, 1961. pp. 1A, 2A. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Hurricane 'Edith' Deepens Rapidly". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. September 7, 1971. pp. 1A, 4A. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Belize Marked 45th Anniversary of Deadly Hurricane Hattie". Belize National Emergency Management Organization (NEMO) (Press release). NEMO Press Officer. November 2, 2006. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- David M. Roth (October 16, 2008). Hurricane Jenny – October 30 November 2, 1961. Weather Prediction Center (Report). College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Hurricane Jenny, November 6-8, 1961 (PDF). United States Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/metadata-1961-1965.pdf

- Humberto Bravo Alavarez; Rodolfo Sosa Echeverria; Pablo Sanchez Alavarez; Arturo Butron Silva (June 22, 2006). Riesgo Quimico Asociado a Fenominos Hidrometeorologicos en el Estado de Verzacruz (PDF). Inundaciones 2005 en el Estado de Veracruz (Report) (in Spanish). Universidad Veracruzana. p. 317. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- "Go Blame An Ill Wind". The Miami News. June 9, 1961. p. 1. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 11, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2014.