1974 Atlantic hurricane season

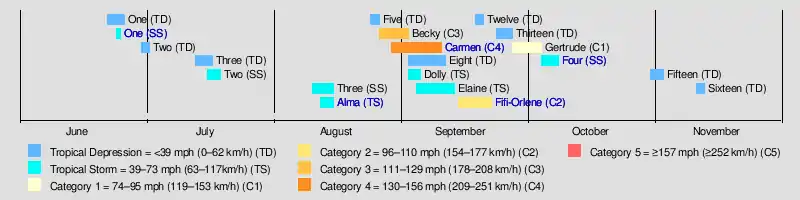

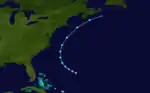

The 1974 Atlantic hurricane season featured Hurricane Fifi, the deadliest Atlantic tropical cyclone since the 1900 Galveston hurricane.[1] The season officially began on June 1 and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The first system, a tropical depression, developed over the Bay of Campeche on June 22 and dissipated by June 26. The season had near average activity, with eleven total storms forming, of which four became hurricanes. Two of those four became major hurricanes, which are Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale.

| 1974 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 22, 1974 |

| Last system dissipated | November 12, 1974 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Carmen |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 928 mbar (hPa; 27.4 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 20 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 8,277 total |

| Total damage | $2 billion (1974 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The most intense storm of the season was Hurricane Carmen, which struck the Yucatán Peninsula at Category 4 intensity and Louisiana at Category 3 intensity. Carmen caused about $162 million in damage, mostly in Louisiana, and 12 deaths. Also highly notable was Hurricane Fifi, which dropped torrential rain in Central America, especially Honduras. The hurricane left more than $1.8 billion in damage and at least 8,210 fatalities. Hurricane Fifi crossed over into the eastern Pacific and was renamed Orlene. In August, poor weather conditions produced by Tropical Storm Alma caused a plane crash in Venezuela, which killed 49 people. Alma caused two additional deaths in Trinidad. Collectively, the tropical cyclones of this year resulted in at least 8,277 deaths and just under $2 billion in damage.

Season summary

The hurricane season officially began on June 1,[2] with the first tropical cyclone developing on June 22. A total of 20 tropical and subtropical cyclones formed, but just 11 of them intensified into nameable storm systems.[3] This was about average compared to the 1950–2000 average of 9.6 named storms.[4] Four of these reached hurricane status,[3] below the 1950–2000 average of 5.9.[4] Furthermore, two storms reached major hurricane status;[3] near the 1950–2000 average of 2.3.[4] Collectively, the cyclones of this season caused at least 8,277 deaths and just under $2 billion in damage.[5] The Atlantic hurricane season officially ended on November 30,[2] with the final cyclone dissipating on November 12.[3]

Similar to the previous two seasons, much of the tropics were dominated by extensive upper-level westerlies and colder than normal sea surface temperatures, producing unfavorable conditions, though to a lesser extent than in 1972 and 1973. Wind shear generated by the westerlies covered a smaller area, while sea surface temperatures in the tropics were generally above the threshold for tropical cyclogenesis. All named storms developed in regions with ocean temperatures exceeding 80 °F (27 °C).[6]

Tropical cyclogenesis began in June, with a tropical depression developing over the Bay of Campeche on June 22, followed by Subtropical Storm One over the Gulf of Mexico two days later. Three cyclones formed in July – two tropical depressions and a subtropical storm. August featured five systems, including Alma, Becky, Carmen, a subtropical storm, and a tropical depression. September was the most active month, with Dolly, Elaine, Hurricane Fifi, Gertrude, and three tropical depressions forming. Subtropical Storm Four and a tropical depression developed in October. The season's final system, a tropical depression, formed on November 10 and dissipated by November 12.[3]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 61.[7] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 34 knots (39 mph, 63 km/h) or tropical storm strength.[8]

Systems

Tropical Depression One

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

.JPG.webp)  | |

| Duration | June 22 – June 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

A low-pressure formed over the Bay of Campeche near Veracruz by June 1. Although a reconnaissance aircraft flight failed to locate a closed circulation early on June 22, surface observations in Mexico showed evidence of a circulation later that day.[9] A tropical depression was estimated to have formed at 12:00 UTC on June 22 while situated just offshore Montepío, Veracruz.[3] Initially, the depression moved northeastward and appeared well-organized. However, by the following day, convection associated with the depression began weakening after an upper low pressure trough intensified over the eastern United States. Convection flared over the eastern Gulf of Mexico, but a second circulation had developed by June 24, with that system becoming Subtropical Storm One.[9]

The depression, now moving slowly northeastward, redeveloped well-organized convection by June 25. However, shortly thereafter, the depression began to lose tropical characteristics due to interaction with atmospheric trough of low pressure. By June 26, the depression completed its extratropical transition over the eastern Gulf of Mexico.[9] The remnants of the depression accelerated to the northeast and moved across Florida, before moving along the East Coast of the United States and then dissipating over New England by June 30. The remnants of the depression brought mostly light rainfall to East Coast states, with a peak total of 7.2 in (180 mm) in Avon Park, Florida.[10]

Subtropical Storm One

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 24 – June 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression One formed over the Bay of Campeche on June 22. As shower and thunderstorm activity associated with the depression diminished, convection flared over the eastern Gulf of Mexico on June 24, while a reconnaissance aircraft flight revealed that a closed circulation had developed over the south-central Gulf of Mexico.[9] Therefore, it is estimated that a subtropical depression formed around 18:00 UTC on June 24. Early the following day, the subtropical depression intensified into a subtropical storm. Accelerating northeastward, the subtropical storm strengthened slightly further before making landfall near Clearwater, Florida, just after 06:00 UTC with winds of 50 mph (85 km/h). Although centered over Florida, the system intensified further, peaking with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) around 12:00 UTC on June 25. After exiting Florida, the cyclone quickly began extratropical later that day, with the remnants dissipating offshore North Carolina on June 27.[3]

Portions of Florida experienced heavy precipitation, particularly the Tampa Bay Area. A peak rainfall total of 11.38 in (289 mm) was observed at the St. Pete–Clearwater International Airport.[11] The storm brought flooding and erosion to parts of west Central Florida. Overall, approximately $24.8 million in damage occurred in Florida, with roughly half of that total incurred to beaches, bridges, drainage systems, roads, sewers, and utilities. Three deaths were reported in the state, all due to drowning.[12]

Subtropical Storm Two

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

.JPG.webp)  | |

| Duration | July 16 – July 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A convective area of cloudiness existed northeast of the Bahamas in mid July in response to a stationary frontal boundary. On July 15, satellite imagery suggested the presence of a weak circulation within the system.[6] Around 00:00 UTC on the following day, a subtropical depression formed about 210 mi (340 km) northeast of the Bahamas. Moving northeastward, the cyclone slowly strengthened, becoming a subtropical storm at about 12:00 UTC on July 17.[3] Late on the next day, the ship Export Adventurer observed winds of 54 mph (87 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 1,006 mbar (29.7 inHg). Based on these observations,[6] the storm peaked with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) on July 18. By the next day, the cyclone began weakening.[3] Around 00:00 UTC on July 20, the subtropical storm was absorbed a large extratropical low,[6] which dissipated well east of Newfoundland several hours later.[3]

Subtropical Storm Three

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

.JPG.webp)  | |

| Duration | August 10 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 992 mbar (hPa) |

A frontal wave formed along a stationary front which ended from near Cape Hatteras northeastward.[6] At 12:00 UTC on August 10, a subtropical storm developed between Bermuda and New England. The storm moved southeastward and then northeastward, before turning northward early on August 12. Drifting northward, the cyclone continued to intensify. Around 12:00 UTC on August 14, the system peaked with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 992 mbar (29.3 inHg),[3] based on ship observations.[6] Later that day, the cyclone curved east-northeastward and accelerated,[3] while its circulation became increasingly ill-defined, resembling that of a front, near Sable Island at about 00:00 UTC on August 15. The remnants of the storm were last noted passing over Cape Race several hours later.[6]

Tropical Storm Alma

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on August 9,[13] developing into a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on August 12 while located about 545 mi (875 km) east-southeast of Barbados. Steered rapidly west by an abnormally strong subtropical ridge, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Alma by noon UTC the next day. Six hours later, Alma attained peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) in accordance with data from a reconnaissance aircraft. Early on August 14, Alma made landfall in Trinidad as a minimal tropical storm, becoming the southernmost-landfalling system on the island in 41 years. The system's circulation entered Venezuela and interacted with mountainous terrain, where it dissipated by 12:00 UTC on August 15.[3][6]

The storm produced a wind gust as high as 91 mph (146 km/h) on Trinidad at Savonetta.[14] Alma left heavy damage in Trinidad, amounting to approximately $5 million,[15] making it the most destructive cyclone of the 20th century on the island at that time. The storm damaged about 5,000 buildings,[16] leaving roughly 500 people homeless. Additionally, the cyclone ruined about 17,750 acres (7,180 ha) of crop fields. Two fatalities occurred in Trinidad,[15] including one person who was struck by flying debris.[17] Alma's heavy rainfall was responsible for a plane crash on Isla Margarita off the Venezuelan coast, killing the 49 people on board.[18]

Tropical Depression Five

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 24 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) |

Around 12:00 UTC on August 24, a tropical depression developed in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico. Moving northwestward, the depression organized further, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 35 mph (55 km/h).[3] It was on the verge of attaining tropical storm status,[19] but made landfall in Texas between Galveston and Freeport on August 26. The depression promptly dissipated.[3]

The depression produced heavy rainfall in Texas, especially in the central parts of the state,[19] with a peak total of 10.75 in (273 mm) in Burnet.[11] A weak cold front, combined with the depression,[20] brought flooding portions of Texas, especially Bell County. In Killeen and Harker Heights, more than 100 people fled their homes, as well as about 50 people from a mobile home park in Nolanville. Flooding damaged 47 homes, 37 mobile homes, and a number of cars. Damage in Bell County was estimated at $100,000. A pickup truck was swept off a low-water crossing at Fort Hood, drowning one occupant of the vehicle.[21] The depression and its remnants also produced rainfall in Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Oklahoma.[19]

Hurricane Becky

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 26 – September 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 977 mbar (hPa) |

The National Hurricane Center first began monitoring an area of shower and thunderstorm activity northeast of the Leeward Islands on August 20. After five days, a circulation became visible on satellite imagery. The disturbance tracked northwest, and both ships observations and satellite imagery indicated the formation of a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on August 26; at the time, it was centered about 440 mi (710 km) south-southwest of Bermuda. Following designation, the depression curved north and then northeast as it rounded the western periphery of a ridge near the Azores. A light shear environment allowed it to intensify into Tropical Storm Becky by 06:00 UTC on August 28 and further into a hurricane by 18:00 UTC that day.[22]

Around 12:00 UTC on August 29, Becky intensified into a Category 2 hurricane.[22] Early on August 30, the system intensified into a Category 3,[3] and by 12:00 UTC, the storm attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure 977 mbar (28.9 inHg), based on observations by a reconnaissance aircraft. Thereafter, Becky accelerated eastward and weaken weakening, falling to tropical storm intensity early on September 2. Later that day, the cyclone merged with a frontal zone northwest of the Azores. Although Becky never posed a threat to land, the storm crossed several major shipping routes.[22]

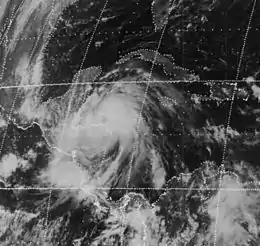

Hurricane Carmen

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 29 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min) 928 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave crossed the western coast of Africa on August 23,[6] organizing into a tropical depression by 06:00 UTC on August 29 about 365 mi (585 km) east of Guadeloupe. The newly-designated cyclone was slow to intensify initially,[3] with limited inflow and a majority of its circulation over the Greater Antilles.[6] It strengthened into Tropical Storm Carmen early on August 30 and further into a hurricane by 12:00 UTC on August 31.[3] Upon entering the western Caribbean Sea and amid a low wind shear environment, Carmen began a period of rapid intensification and attained peak winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) before moving ashore just north of Chetumal, Quintana Roo. Carmen weakened significantly over the Yucatán Peninsula, falling to tropical storm intensity by 00:00 UTC on September 3.[3]

Carmen emerged into the Bay of Campeche late on September 3 and almost immediately executed a turn toward the north in response to falling pressures over the Southern United States.[3][6] The cyclone steadily re-intensified over the Gulf of Mexico,[3] and a reconnaissance aircraft into the storm around 00:00 UTC on September 8 found that maximum winds had again increased to 150 mph (240 km/h). As Carmen approaching the coastline of Louisiana, radar indicated the presence of drier air entering the eastern semicircle of the circulation,[6] and the cyclone moved ashore south of Morgan City with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h). It turned northwest and then west-northwest after landfall and was last monitored as a tropical depression southeast of Waco, Texas, at 06:00 UTC on September 10.[3]

Carmen brought heavy rainfall and a tornado to Puerto Rico, causing about $2 million in damage.[6] Flooding in Jamaica resulted in three people drowning.[23] In Mexico, the storm left hundreds of people homeless in Chetumal and damaged the homes and assets of more than 5,000 people.[24][25] Four deaths and about $10 million in damage occurred in Mexico.[26] In Louisiana, the storm produced sustained winds up to 110 mph (180 km/h) near Amelia. Along the coast, tides ranged from 4–6 ft (1.2–1.8 m) mean sea level, flooding homes with up to 4 ft (1.2 m) of water or sweeping away some of them into the swamp. Throughout the state, the hurricane inflicted minor damage to 1,015 homes, major damage to 722 homes, and complete destruction to 14 homes. Additionally, 697 mobile homes suffered major damage, while 41 other suffered destruction. However, much of the damage in the state was incurred to crops. Cotton, soybean, sugarcane, and rice crops collectively experienced about $116.8 million in damage. Overall, Carmen caused about $150 million in Louisiana and five deaths in the state. Freshwater and tidal flooding to a lesser degree occurred in the other Gulf Coast states.[27]

Tropical Storm Dolly

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 2 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

An area of shower and thunderstorm activity became concentrated underneath an upper-level low in the west Atlantic on August 30. The disturbance drifted west-northwest while steadily organizing, and a ship report around 18:00 UTC on September 2 indicated the formation of a tropical depression about 395 mi (635 km) south-southwest of Bermuda. Although the cyclone was embedded within a high wind shear environment, a reconnaissance mission into the storm the next afternoon found that it had intensified into Tropical Storm Dolly and attained its peak winds of 50 mph (85 km/h). The storm recurved northeast ahead of an approaching trough and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by 12:00 UTC on September 5 offshore the coastline of Nova Scotia.[3][6]

Tropical Storm Elaine

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 4 – September 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 1001 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on August 30 and acquired sufficient organization to be declared a tropical depression by 18:00 UTC on September 4 roughly 715 mi (1,150 km) east of Guadeloupe. The newly-formed cyclone moved northwest for several days, maintaining its status as a tropical depression despite the absence of a closed low-level circulation in several reconnaissance missions.[28] It eventually intensified into Tropical Storm Elaine east of North Carolina by 18:00 UTC on September 9, and with the aid of light upper-level winds, reached peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) early the next morning. Steered northeast by an approaching trough, Elaine interacted with a cold front and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone by 00:00 UTC on September 14 over the northern Atlantic.[3][6]

Hurricane Fifi-Orlene

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 14 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min) 970 mbar (hPa) |

A west-northwestward-moving tropical wave developed into a tropical depression over the eastern Caribbean on September 14. Two days later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Fifi just off the coast of Jamaica. The storm quickly intensified into a hurricane the following afternoon and attained its peak intensity on September 18 as a strong Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h). Maintaining hurricane intensity, Fifi brushed the northern coast of Honduras before making landfall in Belize with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) the following day. The storm quickly weakened after landfall, becoming a depression late on September 20. Continuing westward, the former hurricane began to interact with another system in the eastern Pacific.[3] Early on September 22, Fifi re-attained tropical storm status before fully regenerating into a new tropical cyclone, Tropical Storm Orlene.[29] The storm traveled in an arcuate path offshore Mexico and intensified into a Category 2 hurricane before making landfall in Sinaloa on September 24 and then quickly dissipating.[30]

Fifi brought heavy rainfall to some of the Greater Antilles, especially Jamaica, which recorded precipitation totals exceeding 8 in (200 mm). Parts of the capital city of Kingston were inundated with about 2 ft (0.61 m). The storm caused hundreds of thousands of dollars in damage in Jamaica.[31] While moving westward along the north coast of Honduras, Fifi lashed the country with strong winds and torrential, unrelenting rainfall. Many coastal cities were more than 80% destroyed, while at least 150,000 people were left homeless. The storm also completely destroyed the country's banana crops. Fifi caused at least 8,000 deaths and nearly $1.8 billion in damage in Honduras.[1][32] Other Central American countries were also affected, especially Guatemala. Torrential rainfall in Guatemala caused flooding which washed away or destroyed numerous bridges, roads, and homes. At least 200 people were killed, making Fifi the deadliest in the country in nearly 20 years.[31] In El Salvador, heavy rainfall from the outer bands of the storm led to flooding which killed 10 people.[33] Flooding in Nicaragua left hundreds of people homeless in some villages including in Jinotega, while communities such as La Conquista, Dulce Nombre, San Gregorio, and San Vicente were left isolated after roads washed away.[34] In Belize, winds and rainfall combined to damage or demolish hundreds of homes.[31] The country's banana crop was completely destroyed.[35]

Hurricane Gertrude

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 27 – October 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 999 mbar (hPa) |

A disturbance developed within the Intertropical Convergence Zone just off the western coast of Africa on September 22. The system moved west-northwest and steadily coalesced, organizing into a tropical depression by 12:00 UTC on September 27 about 985 mi (1,585 km) east-southeast of Barbados. The storm was slow to develop at first, intensifying into Tropical Storm Gertude by 18:00 UTC on September 28. However, a reconnaissance aircraft flight six hours later indicated Gertude had intensified into a hurricane and attained peak winds of 75 mph (120 km/h), although its winds were transient and the storm featured an abnormally high surface pressure. After temporarily stalling, Gertude resumed its west-northwest motion while steadily weakening under the influence of strong upper-level winds. It passed through the southern Leeward Islands on October 2 and dissipated over the eastern Caribbean by 00:00 UTC on October 4.[3][6]

Subtropical Storm Four

| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 4 – October 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A low-pressure area developed near just north of eastern Cuba along the axis of a quasi-stationary cold front.[6] The low became a subtropical depression on October 4. Shortly before striking Andros Island on October 6, the system strengthened into a subtropical storm. The storm made its closest approach to Florida early on October 7. Peaking with sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h), the system veered northward and then northeastward,[3] but nonetheless caused heavy rainfall and coastal flooding on land in Florida.[6] While paralleling offshore North Carolina and South Carolina, the storm began to slowly weaken.[3] By late on October 8, the subtropical cyclone merged with a cold front while well east of Cape Hatteras.[6] The extratropical remnants persisted for several more hours, before dissipating on October 9.[3]

Gale force winds were observed by ships and land stations in the Bahamas. The storm and a stationary high pressure system over the Eastern United States resulted in strong winds and rough seas along the coast of Florida for several days, especially on October 6. Many coastal areas observed sustained winds of 25 to 40 mph (40 to 64 km/h), with higher gusts. The storm also produced isolated pockets of heavy rainfall, including 14 in (360 mm) of precipitation in Boca Raton.[6] Dozens of homes were flooded in Boca Raton and Pompano Beach.[36][37] The heavy rainfall destroyed about 50% of winter vegetable crops in Broward County and about 25% of the eggplant crop and about 5%-10% of other crops in Palm Beach County.[38][39] The storm also brought rainfall and abnormally high tides to Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina,[6] and Bermuda.[11] Damage totaled at least $600,000.[40][41]

Other systems

In addition to the other tropical depressions and the named storms, several more tropical cyclones developed, but failed to reach tropical storm status. The first such system developed just offshore the east coast of Africa on June 30. The depression moved westward for a few days, until dissipating on July 2. Another system formed over the northeastern Gulf of Mexico on July 13. Tracking west-southwestward, the depression curved northward on July 16. Late the following day, it made landfall near Caplen, Texas, and promptly dissipated. Another cyclone, classified as Tropical Depression Nine, formed offshore Guinea on September 2. The depression was long-lasting and moved west-northwestward across the Atlantic for several days. Passing north of Puerto Rico on September 9,[3] light to moderate rainfall totals were reported on the island and in the United States Virgin Islands, with a peak total of 5.38 in (137 mm) at a substation in Corozal, Puerto Rico.[11] The depression dissipated near Inagua island in the Bahamas on September 1.[3]

A tropical depression formed over the western Atlantic on September 18. The depression remained weak and moved in a semi-circular path near Bermuda, before dissipating on September 20. The next tropical depression originated over the northwestern Caribbean on September 23. Moving northwestward, the storm grazed the northeastern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula on the following day and then entered the Gulf of Mexico. By September 25, the depression turned to the northeast. It weakened and dissipated just offshore the west coast of Florida near Cedar Key on September 27. Another depression developed well northeast of the Lesser Antilles on October 30. Moving quickly north-northeastward, the depression remained weak and then dissipated well to the southwest of the Azores on November 2. The final minor depression, and last tropical cyclone, of the season formed north of Hispaniola on November 10. Moving slowly northward for a few days, the depression dissipated by November 12.[3]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1974.[2] Storms were named Carmen, Elaine and Gertrude for the first time in 1974. The names Carmen and Fifi were later retired.[42] Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 1974 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s) – denoted by bold location names – damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses will be additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but are still related to that storm. Damage and deaths will include totals while the storm was extratropical or a wave or low, and all of the damage figures are in 1974 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | June 22 – 26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | Mexico | Unknown | None | |||

| One | June 24 – 25 | Subtropical storm | 65 (100) | 1000 | Southeastern United States | $24.8 million | 3 | |||

| Two | June 30 – July 2 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Three | July 13 – 17 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | United States Gulf Coast | None | None | |||

| Two | July 14 – 19 | Subtropical storm | 50 (85) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Three | August 10 – 15 | Subtropical storm | 60 (95) | 992 | None | None | None | |||

| Alma | August 12 – 15 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 1007 | Windward Islands, Venezuela, Netherlands Antilles, Colombia | $5 million | 51 | |||

| Five | August 24 – 26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | United States Gulf Coast | $100 thousand | 1 | |||

| Becky | August 26 – September 2 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 977 | None | None | None | |||

| Carmen | August 29 – September 10 | Category 4 hurricane | 150 (240) | 928 | Lesser Antilles, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Mexico, Belize, Southern United States | $162 million | 12 | |||

| Eight | September 2 – 11 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | Leeward Islands, Bahamas | Unknown | None | |||

| Dolly | September 2 – 5 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Elaine | September 4 – 13 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 1001 | None | None | None | |||

| Fifi | September 14 – 22 | Category 2 hurricane | 110 (175) | 971 | Hispaniola, Jamaica, Central America, Mexico | $1.8 billion | ≥8,210 | |||

| Twelve | September 18 – 20 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | Unknown | Bermuda | Unknown | None | |||

| Thirteen | September 23 – 27 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | Unknown | Mexico, Southeastern United States | Unknown | None | |||

| Gertrude | September 25 – October 4 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 999 | Windward Islands | Unknown | None | |||

| Four | October 4 – October 8 | Subtropical storm | 50 (85) | 1006 | Cuba, Bahamas, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Bermuda | $600 thousand | None | |||

| Fifteen | October 30 – November 2 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Sixteen | November 10 – November 12 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | Unknown | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 20 systems | June 22 – November 12 | 150 (240) | 928 | $1.99 billion | ≥8,277 | |||||

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

- 1974 Pacific hurricane season

- 1974 Pacific typhoon season

- 1974 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone seasons: 1973–74, 1974–75

References

- Edward N. Rappaport and Jose Fernandez-Partagas (May 28, 1995). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996 (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- "Hurricane Season Begins". The Index-Journal. Associated Press. June 1, 1974. p. 2. Retrieved April 23, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Philip J. Klotzbach and William M. Gray (December 8, 2006). Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2007 (Report). Boulder, Colorado: Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 18 December 2006. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- John R. Hope (1975). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1974". National Hurricane Center. American Meteorological Society. 103 (4): 285–293. Bibcode:1975MWRv..103..285H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1975)103<0285:AHSO>2.0.CO;2.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 16 (6): 5. June 1974. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide 1900-present (PDF) (Report). Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. August 1993. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- Aircraft Accident: Vickers 749 Viscount YV-C-AMX Isla Margarita (Report). Aviation Safety Network. February 12, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 16 (8): 5. August 1974. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "Storm May Regain Hurricane Strength". The Argus-Press. Associated Press. September 4, 1974. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Hurricane Gathers Strength In Gulf". Beaver County Times. United Press International. September 6, 1974. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 16 (9): 9. September 1974. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Aid Efforts Start For Honduras, Fifi Deaths Soar". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. September 24, 1974. p. 7. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Edward N. Rappaport and Jose Fernandez-Partagas (May 28, 1995). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996 (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- "Floods Still Threaten Texas; Fifi In Mexico". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Associated Press. September 21, 1974. p. 7. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Tony Benjamin; Virginia Snyder (October 7, 1974). "Runoff floods low areas". Boca Raton News. p. 1. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- "Worst of Deluge, Winds May Be Over". The Palm Beach Post. October 8, 1974. p. 2. Retrieved April 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- John R. Hope (1975). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1974". National Hurricane Center. American Meteorological Society. 103 (4): 285–293. Bibcode:1975MWRv..103..285H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1975)103<0285:AHSO>2.0.CO;2.

- Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). "Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- David Levinson (2008-08-20). "2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- Paul J. Hebert (1974). Un-named Subtropical Storm and Tropical Depression, June 21 – 27, 1974 (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- David M. Roth (March 6, 2013). Tropical Depression #2 - June 26-30, 1974 (Report). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 16 (6): 5. June 1974. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- PJH (August 26, 1974). Preliminary Report: Tropical Storm Alma – August 12–15, 1974 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- Tropical Cyclones Affecting Trinidad and Tobago 1725-2000 (PDF) (Report). Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service. May 2, 2002. p. 10. Archived from the original on December 23, 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2019.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide 1900-present (PDF) (Report). Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance. August 1993. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- USG Disaster Assistance for Relief of Victims of Tropical Storm Alma in Trinidad (JPG) (Report). American Embassy at Port of Spain. August 30, 1974. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "Alma Hits Trinidad, Kills One". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Associated Press. August 15, 1974. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- Aircraft Accident: Vickers 749 Viscount YV-C-AMX Isla Margarita (Report). Aviation Safety Network. February 12, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- "Tropical Depression Four - August 24-28, 1974". Weather Prediction Center. March 6, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "Showers Continue In Bonham Area". The Bonham Daily Favorite. August 28, 1974. p. 1. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 16 (8): 5. August 1974. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- Gilbert B. Clark (September 21, 1974). Preliminary Report: Hurricane Becky – August 26–September 2, 1974 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- "Storm May Regain Hurricane Strength". The Argus-Press. Associated Press. September 4, 1974. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Hurricane watch out along Gulf". Bangor Daily News. Associated Press. September 6, 1974. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Hurricane stalls, getting weaker". The Montreal Gazette. United Press International. September 4, 1974. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Hurricane Gathers Strength In Gulf". Beaver County Times. United Press International. September 6, 1974. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. 16 (9): 9. September 1974. ISSN 0039-1972. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- Preliminary Report: Tropical Storm Elaine – September 4–13, 1974 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- Sharon Towry (June 1975). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones in 1974: Part 2". Monthly Weather Review. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 103 (6): 550–559. Bibcode:1975MWRv..103..550T. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1975)103<0550:ENPTCP>2.0.CO;2.

- Preliminary Report: Hurricane Fifi. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1975. p. 1. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

- David Longshore (2008). Encyclopedia of Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Cyclones New Edition. Checkmark Books. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-8160-7409-9.

- "Aid Efforts Start For Honduras, Fifi Deaths Soar". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. September 24, 1974. p. 7. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Floods Still Threaten Texas; Fifi In Mexico". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Associated Press. September 21, 1974. p. 7. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- huracán Fifí (1974) (Report) (in Spanish). Dirección General de Meteorología. 2004. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- "A Much-Deflated Fifi Moves Into Mexico". The Miami Herald. Associated Press. September 21, 1974. p. 18A. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- Tony Benjamin; Virginia Snyder (October 7, 1974). "Floods". Boca Raton News. p. 3. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- Debbi Smith (October 7, 1974). "High Water, Strong Winds Batter Gold Coast Homes, Damage Streets". Fort Lauderdale News. p. 1. Retrieved April 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Crop Losses May Boost Prices". Fort Lauderdale News. October 7, 1974. p. 2. Retrieved April 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lynda Burgiss (October 8, 1974). "Bean Crop Hurt by the Storm". The Palm Beach Post. p. 22. Retrieved April 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tony Benjamin; Virginia Snyder (October 7, 1974). "Runoff floods low areas". Boca Raton News. p. 1. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- "Worst of Deluge, Winds May Be Over". The Palm Beach Post. October 8, 1974. p. 2. Retrieved April 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2019.