A Study in Scarlet

A Study in Scarlet is an 1887 detective novel written by Arthur Conan Doyle. The story marks the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, who would become the most famous detective duo in popular fiction. The book's title derives from a speech given by Holmes, a consulting detective, to his friend and chronicler Watson on the nature of his work, in which he describes the story's murder investigation as his "study in scarlet": "There's the scarlet thread of murder running through the colourless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it, and isolate it, and expose every inch of it."[1]

First edition in annual cover, 1887 | |

| Author | Arthur Conan Doyle |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Series | Sherlock Holmes |

| Genre | Detective novel |

| Publisher | Ward Lock & Co |

Publication date | 1887 in annual (1888 in book form) |

| Followed by | The Sign of the Four |

| Text | A Study in Scarlet at Wikisource |

The story, and its main characters, attracted little public interest when it first appeared. Only 11 complete copies of the magazine in which the story first appeared, Beeton's Christmas Annual for 1887, are known to exist now and they have considerable value.[2] Although Conan Doyle wrote 56 short stories featuring Holmes, A Study in Scarlet is one of only four full-length novels in the original canon. The novel was followed by The Sign of the Four, published in 1890. A Study in Scarlet was the first work of detective fiction to incorporate the magnifying glass as an investigative tool.[3]

Plot

Part I: The Reminiscences of Watson

In 1881, Doctor John Watson has returned to London after serving in the Second Anglo-Afghan War. He visits the Criterion Restaurant and runs into an old friend named Stamford, who had been a dresser under him at St. Bartholomew's Hospital. Watson tells Stanford he is looking for a place to live before his nine-month half-pay pension runs out. Stamford mentions that an acquaintance of his, Sherlock Holmes, is looking for someone to split the rent at a flat at 221B Baker Street, but he cautions Watson about Holmes's eccentricities.

Stamford takes Watson back to St. Bartholomew's where, in a laboratory, they find Holmes experimenting with a reagent, seeking a test to detect human hemoglobin. Holmes explains the significance of bloodstains as evidence in criminal trials. Watson raises their parallel quests to find a place to live. At Holmes's prompting, the two review their various shortcomings to make sure that they can live together. After seeing the rooms at 221B, they move in and grow accustomed to their new situation. Holmes reveals that he is a "consulting detective" and that his frequent guests are clients. Facing Watson's doubts about some of his claims, Holmes casually deduces to Watson that one visitor, a messenger from Scotland Yard, is also a retired Marine sergeant. When the man confirms this, Watson is astounded.

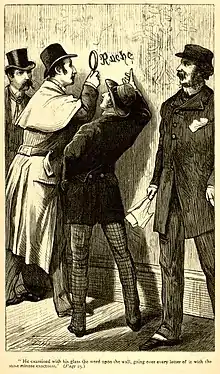

The telegram requests a consultation in a murder case. Holmes is reluctant to help because credit would go entirely to the officials, but Watson urges him to reconsider, and, at Holmes' suggestion, accompanies him to the crime scene, an abandoned house. Holmes observes the pavement and garden leading up to the house before he and Watson meet Inspectors Gregson and Lestrade. The male corpse is identified as a wealthy man named Enoch Drebber. They also learn from documents found on his person that he was in London with his secretary, Joseph Stangerson. On one wall, written in red, is "RACHE". Holmes remarks that it is the German word for "revenge". He deduces that the victim died from poison and supplies a description of the murderer. Holmes says "RACHE" was a ploy to fool the police. Upon moving Drebber's body, they discover a woman's gold wedding ring.

Holmes and Watson visit the home of the constable who found the corpse and learn that a seemingly drunk loiterer had attempted to approach the crime scene. Holmes reasons that the murderer returned on realising he'd forgotten the wedding ring.

Holmes dispatches some telegrams including an order for a newspaper notice about the ring. He also buys a facsimile of it. He guesses that the murderer, having already returned to the scene of the crime for it, would come to retrieve it. The advertisement is answered by an old woman who claims that the ring belongs to her daughter. Holmes gives her the duplicate, follows her, and returns to Watson later that night, explaining that she took a cab, he hopped onto the back of it, and when it stopped, he found that she had vanished. This leads Holmes to believe that it was an accomplice in disguise.

A day later, Gregson visits Holmes and Watson, telling them that he has arrested a suspect. He had gone to Madame Charpentier's Boarding House where Drebber and Stangerson had stayed before the murder. He learned from her that Drebber, a drunk, had attempted to kiss Mrs. Charpentier's daughter, Alice, which caused their immediate eviction. Drebber, however, came back later that night and attempted to grab Alice, prompting her older brother to attack him. He attempted to chase Drebber with a cudgel but claimed to have lost sight of him. Gregson has him in custody on this circumstantial evidence.

Lestrade then arrives revealing that Stangerson has been murdered. Lestrade had gone to interview Stangerson after learning where he had been rooming. His body was found near the hotel window, stabbed through the heart. Above his body was written "RACHE". The only things Stangerson had with him were a novel, a pipe, a telegram saying "J.H. is in Europe", and a small box containing two pills. The pillbox Lestrade still has with him. Holmes tests the pills on an old and sickly Scottish terrier in residence at Baker Street. The first pill produces no evident effect, but the second kills the terrier. Holmes deduces that one was harmless and the other poison.

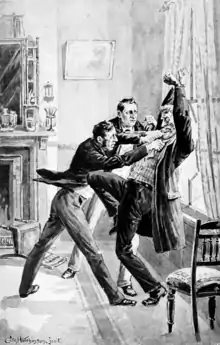

Just at that moment, a very young street urchin named Wiggins arrives. He is the leader of the Baker Street Irregulars, a group of street children Holmes employs to help him occasionally. Wiggins states that he's summoned the cab Holmes wanted. Holmes sends him down to fetch the cabby, claiming to need help with his luggage. When the cabby comes upstairs and bends for the trunk, Holmes handcuffs and restrains him. He then announces the captive cabby as Jefferson Hope, the murderer of Drebber and Stangerson.

Part II: "The Country of the Saints"

The story flashes back to the Salt Lake Valley in Utah in 1847, where John Ferrier and a little girl named Lucy, the only survivors of a small party of pioneers, lie down near a boulder to die from dehydration and hunger. They are discovered by a large party of Latter-day Saints led by Brigham Young. The Mormons rescue Ferrier and Lucy on the condition that they adopt and live under their faith. Ferrier, who has proven himself an able hunter, adopts Lucy and is given a generous land grant with which to build his farm after the party constructs Salt Lake City. Years later, a now-grown Lucy befriends and falls in love with a man named Jefferson Hope.

Lucy and Hope become engaged, with the ceremony scheduled to take place after Hope's return from a two-month-long journey for his job. However, Ferrier is visited by Young, who reveals that it is against the religion for Lucy to marry Hope, a non-Mormon. He states that Lucy should marry Joseph Stangerson or Enoch Drebber—both sons of members of the church's Council of Four—though Lucy may choose which one. Ferrier and Lucy are given a month to decide.

Ferrier, who has sworn to never marry his daughter to a Mormon, immediately sends out a word to Hope for help. When he is visited by Stangerson and Drebber, Ferrier is angered by their arguments over Lucy and throws them out. Every day, however, the number of days Ferrier has left to marry off Lucy is painted somewhere on his farm in the middle of the night. Hope finally arrives on the eve of the last day, and sneaks his love and her adoptive father out of their farm and away from Salt Lake City. However, while he is hunting for food, Hope returns to a horrific sight: a makeshift grave for the elder Ferrier. Lucy is nowhere to be seen. Determined to devote his life to revenge, Hope sneaks back into Salt Lake City, learning that Stangerson murdered Ferrier and that Lucy was forcibly married to Drebber. Lucy dies a month later from a broken heart; Drebber, who inherited Ferrier's farm, becomes wealthy after converting the land to cash and is indifferent to Lucy's death. Hope then breaks into Drebber's house the night before Lucy's funeral to kiss her body and remove her wedding ring. Swearing vengeance, Hope stalks the town, coming close to killing Drebber and Stangerson on numerous occasions.

Hope begins to suffer from an aortic aneurysm, causing him to leave the mountains to earn money and recuperate. When he returns several years later, he learns that Drebber and Stangerson have fled Salt Lake City after a schism between the Mormons. Hope searches the United States, eventually tracking them to Cleveland; Drebber has Hope arrested as an old rival in love; released from jail, Hope finds that the pair then flees to Europe, where for a month he stays on their trail (St. Petersburg, Copenhagen, Paris), eventually landing in London.

This is the story the handcuffed Hope willingly tells to Holmes, Lestrade, Gregson, and Watson. In London, Hope became a cabby and eventually found Drebber and Stangerson at Euston station about to depart to Liverpool for America. Having missed the first train, Drebber instructed Stangerson to wait at the station and then returned to Madame Charpentier's house. After an altercation with Madame Charpentier's son, Drebber got into Hope's cab and spent several hours drinking. Eventually, Hope took him to the house on Brixton Road, which Drebber drunkenly entered believing it was a hotel. Hope then forced Drebber to recognize him and to choose between two pills, one of which was harmless and the other poison. Drebber took the poisoned pill, and as he died, Hope showed him Lucy's wedding ring. The excitement coupled with his aneurysm had caused his nose to bleed; he used the blood to write "RACHE" on the wall above Drebber to confound the investigators.

Hope realized, upon returning to his cab, that he had forgotten Lucy's ring, but upon returning to the house, he found Constable Rance and other police officers, whom he evaded by acting drunk. He then had a friend pose as an old lady to pick up the supposed ring from Holmes's advertisement.

Hope then began stalking Stangerson's room at the hotel; but Stangerson, on learning of Drebber's murder, refused to come out. Hope climbed into the room through the window and gave Stangerson the same choice of pills, but he was attacked and nearly strangled by Stangerson and forced to stab him in the heart. He has stayed in London only to earn enough money to go back to the United States, although he admits that after twenty years of vengeance, he now has nothing to live for or care about.

After being told of this, Holmes and Watson return to Baker Street; Hope dies from his aneurysm the night before he is to appear in court, a smile on his face. One morning, Holmes reveals to Watson how he had deduced the identity of the murderer (using the one clue of the wedding ring, he had deduced the name from a telegram to the Cleveland Police regarding Drebber's marriage) and how he had used the Irregulars, whom he calls "street Arabs," to search for a cabby by that name. He then shows Watson the newspaper; Lestrade and Gregson are given full credit. Outraged, Watson states that Holmes should record the adventure and publish it. Upon Holmes's refusal, Watson decides to do it himself.

Publication

Conan Doyle wrote the novel at the age of 27 in less than three weeks.[4] As a general practice doctor in Southsea, Portsmouth, he had already published short stories in several magazines of the day, such as the periodical London Society. The story was originally titled A Tangled Skein, and was eventually published by Ward Lock & Co. in Beeton's Christmas Annual 1887, after many rejections. The author received £25 in return for the full rights (although Conan Doyle had pressed for a royalty instead). It was illustrated by David Henry Friston.

The novel was first published as a book in July 1888 by Ward, Lock & Co., and featured drawings by the author's father, Charles Doyle. In 1890, J. B. Lippincott & Co. released the first American version. Another edition published in 1891 by Ward, Lock & Bowden Limited (formerly Ward, Lock & Co.) was illustrated by George Hutchinson. A German edition of the novel published in 1902 was illustrated by Richard Gutschmidt.[5] Numerous further editions, translations and dramatisations have appeared since.

Depiction of Mormonism

According to a Salt Lake City newspaper article, when Conan Doyle was asked about his depiction of the Latter-day Saints' organisation as being steeped in kidnapping, murder and enslavement, he said: "all I said about the Danite Band and the murders is historical so I cannot withdraw that, though it is likely that in a work of fiction it is stated more luridly than in a work of history. It's best to let the matter rest".[6] Conan Doyle's daughter has stated: "You know, father would be the first to admit that his first Sherlock Holmes novel was full of errors about the Mormons."[6] Historians speculate that "Conan Doyle, a voracious reader, would have access to books by Fannie Stenhouse, William A. Hickman, William Jarman, John Hyde and Ann Eliza Young, among others,"[6] in explaining the author's early perspective on Mormonism.

Years after Conan Doyle's death, Levi Edgar Young, a descendant of Brigham Young and a Mormon general authority, claimed that Conan Doyle had privately apologised, saying that "He [Conan Doyle] said he had been misled by writings of the time about the Church"[6] and had "written a scurrilous book about the Mormons."[7]

In August 2011, the Albemarle County, Virginia, School Board removed A Study in Scarlet from the district's sixth-grade required reading list following complaints from students and parents that the book was derogatory toward Mormons.[8][9] It was moved to the reading lists for the tenth-graders, and remains in use in the school media centres for all grades.[10]

Adaptations

Film

As the first Sherlock Holmes story published, A Study in Scarlet was among the first to be adapted to the screen. In 1914, Conan Doyle authorised a British silent film be produced by G. B. Samuelson. In the film, titled A Study in Scarlet, Holmes was played by James Bragington, an accountant who worked as an actor for the only time of his life. He was hired for his resemblance to Holmes, as presented in the sketches originally published with the story.[11] As early silent films were made with film that itself was made with poor materials, and film archiving was then rare, it is now a lost film. The film was successful enough for Samuelson to produce the 1916 film The Valley of Fear.[12]

A two-reel short film, also titled A Study in Scarlet, was released in the United States in 1914, a day after the British film with the same title was released. The American film starred Francis Ford as Holmes, and was not authorised by Doyle. It is also a lost film.[12]

The 1933 film entitled A Study in Scarlet, starring Reginald Owen as Sherlock Holmes and Anna May Wong as Mrs Pyke, bears no plot relation to the novel.[13] Aside from Holmes, Watson, Mrs. Hudson, and Inspector Lestrade, the only connections to the Holmes canon are a few lifts of character names (Jabez Wilson, etc.).[13] The plot contains an element of striking resemblance to one used several years later in Agatha Christie's novel And Then There Were None.[14]

Radio

Edith Meiser adapted A Study in Scarlet into a four-part serial for the radio series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. The episodes aired in November and December 1931, with Richard Gordon as Sherlock Holmes and Leigh Lovell as Dr. Watson.[15]

Parts of the story were combined with "The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton" for the script of "Dr Watson Meets Mr Sherlock Holmes", one of multiple radio adaptations featuring John Gielgud as Sherlock Holmes and Ralph Richardson as Dr. Watson. The episode first aired on the BBC Light Programme on 5 October 1954, and also aired on NBC radio on 2 January 1955.[16]

The story was adapted for the 1952–1969 BBC radio series in 1962 by Michael Hardwick, with Carleton Hobbs as Sherlock Holmes and Norman Shelley as Dr. Watson. It aired on the BBC Home Service.[17]

Another British radio version of the story adapted by Hardwick aired on 25 December 1974, with Robert Powell as Sherlock Holmes and Dinsdale Landon as Watson. The cast also included Frederick Treves as Inspector Gregson, John Hollis as Inspector Lestrade, and Don Fellows as Jefferson Hope.[18]

A radio dramatisation of the story aired on CBS Radio Mystery Theater during its 1977 season, with Kevin McCarthy as Holmes and Court Benson as Watson.[19]

A Study in Scarlet was adapted as the first two episodes of the BBC's complete Sherlock Holmes 1989–1998 radio series. The two-part adaptation aired on Radio 4 in 1989, dramatised by Bert Coules and starring Clive Merrison as Holmes, Michael Williams as Watson, Donald Gee as Inspector Lestrade, and John Moffatt as Inspector Gregson.[20]

It was adapted as a 2007 episode of the American radio series The Classic Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, with John Patrick Lowrie as Holmes, Lawrence Albert as Watson, Rick May as Lestrade, and John Murray as Gregson.[21]

Television

The 1954–1955 television series (with Ronald Howard as Holmes and H. Marion Crawford as Watson) used only the first section of the book as the basis for the episode "The Case of the Cunningham Heritage".[22]

The book was adapted into an episode broadcast on 23 September 1968 in the second season of the BBC television series Sherlock Holmes,[23] with Peter Cushing in the lead role and Nigel Stock as Dr. Watson.

It was adapted as the second episode of the 1979 Soviet television film, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson (the first episode combines the story of their meeting with "The Adventure of the Speckled Band"; the second episode adapts the actual Jefferson Hope case).[24]

A 1983 animated television film adaptation was produced by Burbank Films Australia, with Peter O'Toole voicing Holmes. In both the 1968 television adaptation featuring Peter Cushing and the 1983 animated version featuring Peter O'Toole, the story is changed so that Holmes and Watson already know each other and have been living at 221B Baker Street for some time.

A Study in Scarlet is one of the stories missing from the adaptations made starring Jeremy Brett between 1984 and 1994.[25]

Steven Moffat loosely adapted A Study in Scarlet into "A Study in Pink" as the first episode of the 2010 BBC television series Sherlock featuring Benedict Cumberbatch as a 21st-century Sherlock Holmes, and Martin Freeman as Dr. Watson.[26] The adaptation retains many individual elements from the story, such as the scribbled "RACHE" and the two pills, and the killer's potentially fatal aneurysm (although it is located in his brain rather than his aorta). However, the entire backstory set in America is omitted, and the motivation of the killer is completely different. It also features Moriarty's presence. Also, the meeting of Holmes and Watson is adapted in the Victorian setting in the special "The Abominable Bride".

"The Deductionist", an episode of Elementary, contains many elements of Hope's case, including the motivation of revenge. The story was more closely adapted in the season 4 episode, "A Study in Charlotte."

"The First Adventure", the first episode of the 2014 NHK puppetry series Sherlock Holmes, is loosely based on A Study in Scarlet and "The Adventure of the Six Napoleons". In it, Holmes, Watson and Lestrade are pupils at a fictional boarding school called Beeton School. They find out that a pupil called Jefferson Hope has taken revenge on Enoch Drebber and Joseph Stangerson for stealing his watch. "Scarlet Story", the series' opening theme tune, is named after the novel[27] and the name of "Beeton School" is partially inspired by Beeton's Christmas Annual.[28]

Other media

A Study in Scarlet was illustrated by Seymour Moskowitz for Classics Illustrated comics in 1953. It was also adapted to graphic novel form by Innovation Publishing in 1989 (adapted by James Stenstrum and illustrated by Noly Panaligan) by Sterling Publishing in 2010 (adapted by Ian Edginton and illustrated by I. N. J. Culbard) and by Hakon Holm Publishing in 2013 (illustrated by Nis Jessen).[29]

In 2010, A Study in Scarlet was adapted for the stage by William Amos Jr and Margaret Walther.[30]

In 2014, A Study in Scarlet was adapted again for the stage by Greg Freeman, Lila Whelan and Annabelle Brown for Tacit Theatre.[31] The production premiered at Southwark Playhouse in London in March 2014.[32]

Allusions in other works

In his Naked is the Best Disguise (1974), Samuel Rosenberg notes the similarity between Jefferson Hope's tracking of Enoch Drebber and a sequence in James Joyce's novel Ulysses, though of course Joyce's work did not begin to appear in print until 1918. Several other associations between Conan Doyle and Joyce are also listed in Rosenberg's book.

The British fantasy and comic book writer Neil Gaiman adapted this story to the universe of horror writer H. P. Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos. The new short story is titled "A Study in Emerald" (2004) and is modelled with a parallel structure.

References

- Conan Doyle, A. A Study in Scarlet, "Chapter 4: What John Rance Had to Tell"

- "bestofsherlock.com, Beeton's Christmas Annual 1887: An Annotated Checklist and Census". Bestofsherlock.com. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Sweeney, Susan Elizabeth (2003). "The Magnifying Glass: Spectacular Distance in Poe's "Man of the Crowd" and Beyond". Poe Studies/Dark Romanticism. 36 (1–2): 3. doi:10.1111/j.1754-6095.2003.tb00146.x. S2CID 161345856.

- "Inscribed copy of Sherlock Holmes' debut book for sale" Telegraph, UK. 24 May 2010.

- Klinger, Leslie (ed.). The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, Volume III (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006). pp. 2, 11, 13, 56. ISBN 978-0393058000

- Schindler, Harold (10 April 1994), "The Case Of The Repentant Writer: Sherlock Homes' Creator Raises The Wrath Of Mormons", The Salt Lake Tribune, p. D1, Archive Article ID: 101185DCD718AD35 (NewsBank). Online reprint Online reprint Archived 23 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, with permission, at HistoryToGo.utah.gov by the Utah Division of State History, Utah Department of Heritage and Arts, State of Utah.

- L. Jackson, Newell, ed. (1996). Matters of Conscience: Conversations with Sterling M. McMurrin. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. p. 74. ISBN 1560850876.

- Richardson, Aaron (11 August 2011), "Albemarle removes Sherlock Holmes book from reading list", The Daily Progress

- Kindelan, Katie (12 August 2011), "Virginia School District Deletes Sherlock Holmes Novel From 6th Grade for 'Anti-Mormon' Portrayal", ABC World News, ABC News

- "34 (8.1) Recommendation of Reconsideration for the book "A Study in Scarlet" by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle". Albemarle County Public Schools. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- "Who is this forgotten Sherlock Holmes?". 12 February 2008. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Barnes, Alan (2011). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Titan Books. p. 276. ISBN 9780857687760.

- Bunson, Matthew (1994). Encyclopedia Sherlockiana: an A-to-Z guide to the world of the great detective. Macmillan. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-671-79826-0.

- Taves, Brian (1987). Robert Florey, the French Expressionist. New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. p. 152. ISBN 0-8108-1929-5.

- Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. p. 40. ISBN 978-1629335087.

- Dickerson, Ian (2019). Sherlock Holmes and His Adventures on American Radio. BearManor Media. p. 284. ISBN 978-1629335087.

- De Waal, Ronald Burt (1974). The World Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Bramhall House. p. 390. ISBN 0-517-217597.

- Eyles, Allen (1986). Sherlock Holmes: A Centenary Celebration. Harper & Row. p. 139. ISBN 9780060156206.

- Payton, Gordon; Grams, Martin, Jr. (2015) [1999]. The CBS Radio Mystery Theater: An Episode Guide and Handbook to Nine Years of Broadcasting, 1974-1982 (Reprinted ed.). McFarland. p. 199. ISBN 9780786492282.

- "A Study in Scarlet". The BBC complete audio Sherlock Holmes. Bert Coules. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Wright, Stewart (30 April 2019). "The Classic Adventures of Sherlock Holmes: Broadcast Log" (PDF). Old-Time Radio. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Barnes, Alan (2011). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Titan Books. p. 181. ISBN 9780857687760.

- Alan Barnes (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 178. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- Alan Barnes (2002). Sherlock Holmes on Screen. Reynolds & Hearn Ltd. p. 108. ISBN 1-903111-04-8.

- List of Sherlock Holmes episodes

- Sutcliffe, Tom (26 July 2010). "The Weekend's TV: Sherlock, Sun, BBC1 Amish: World's Squarest Teenagers, Sun, Channel 4". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- 岡崎信治郎、藤田健一編『NHKパペットエンターテインメント シャーロックホームズ 冒険ファンブック』小学館、2014年、32–35頁。

Shinjirō Okazaki and Kenichi Fujita (Ed.) Guidebook of Sherlock Holmes, Tokyo, Shogakukan, 2014, pp. 32–35. - NHK's reply to the enquiry about the origin of the school's name.

- Scott Monty (2012). The Artist Had Brought Out the Full Effect

- Clisham, Kelly (10 August 2010). "Beloved Sleuths Hit the Stage". The Weekender. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- "Tacit Theatre webpage". www.tacittheatre.co.uk. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- "Time Out London review". Retrieved 12 March 2015.

External links

Works related to A Study in Scarlet at Wikisource

Works related to A Study in Scarlet at Wikisource Media related to A Study in Scarlet at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to A Study in Scarlet at Wikimedia Commons- A Study in Scarlet at Project Gutenberg

A Study in Scarlet public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A Study in Scarlet public domain audiobook at LibriVox