A Voyage to Arcturus

A Voyage to Arcturus is a novel by the Scottish writer David Lindsay, first published in 1920. It combines fantasy, philosophy, and science fiction in an exploration of the nature of good and evil and their relationship with existence. Described by critic, novelist, and philosopher Colin Wilson as the "greatest novel of the twentieth century",[1] it was a central influence on C. S. Lewis' Space Trilogy,[2] and through him on J. R. R. Tolkien, who said he read the book "with avidity".[3] Clive Barker called it "a masterpiece" and "an extraordinary work ... quite magnificent."[4]

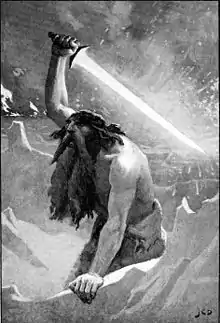

.jpg.webp) Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | David Lindsay |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy, science fiction |

| Publisher | Methuen & Co. Ltd. |

Publication date | 1920 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 303 pp (first edition hardcover) |

| Followed by | The Flight to Lucifer |

An interstellar voyage is the framework for a narrative of a journey through fantastic landscapes. The story is set at Tormance, an imaginary planet orbiting Arcturus, which in the novel (but not in reality) is a double star system, consisting of stars Branchspell and Alppain. The lands through which the characters travel represent philosophical systems or states of mind, through which the main character, Maskull, passes on his search for the meaning of life.

The book sold poorly during Lindsay's lifetime, but was republished in 1946 and many times thereafter. It has been translated into at least ten languages. Critics such as the novelist Michael Moorcock have noted that the book is unusual, but has been highly influential with its qualities of "commitment to the Absolute" and "God-questioning genius".[5]

Context

David Lindsay was born in 1876; his father was a Scottish Calvinist and his mother English. He was brought up in London and Jedburgh in the Scottish borders. He enjoyed reading novels by Walter Scott, Jules Verne, Rider Haggard and Robert Louis Stevenson. He learnt German to read the philosophies of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. He served in the army in the First World War, being called up at the age of 38. He married in 1916. After the war ended in 1918, he moved to Cornwall with his wife to write.[6][5] Lindsay told his friend E. H. Visiak that his greatest influence was the work of George MacDonald.[7]

Contents

Synopsis

Maskull, a man longing for adventures, accepts an invitation from Krag, an acquaintance of his friend Nightspore, to travel to Tormance after a seance. The three set off in a crystal ship from an abandoned observatory in Scotland but Maskull awakens to find himself alone on Tormance. In every land he passes through he usually meets only one or two persons; these meetings often (though not always) end in the death of those he meets, either at his own hand or by that of another. He learns of his own impending death, meets Krag again, and dies shortly after learning that he is in fact Nightspore himself. The book concludes with a final revelation from Krag (who claims to be known on Earth as "Pain") to Nightspore about the origin of the Universe. The author turns out to support a variation of the doctrine of the Demiurge, somewhat similar to that propounded by some Gnostics.

All of the characters and lands are types used to convey the author's critique of several philosophical systems. On Tormance, most such viewpoints or ways of life are accompanied by corresponding new bodily sense organs or modifications of the same, thus each distinct Weltanschauung landscape has its corresponding sensorium.

Chapters

- 1 – The Seance

A seance is organised in Hampstead to which Maskull and Nightspore are invited; their late arrival is marked by a supernatural noise. The medium causes a smiling man to materialise. Krag arrives uninvited, kills the apparition by breaking its neck, and summarily calls Maskull and Nightspore (with whom he was acquainted) out to the street.

- 2 – In the Street

Krag invites Maskull and Nightspore to come to Tormance, a planet orbiting Arcturus, whence the apparition comes. Maskull initially treats the proposal as a joke, but accepts it when Krag shows him, with a small but strangely heavy and potent lens, that Arcturus consists of two suns. Upon questioning from Nightspore, Krag says that Surtur (unknown to Maskull) has gone ahead and that they must follow him.

- 3 – Starkness

Maskull and Nightspore arrive on foot (after travelling by train) at the Scottish observatory of Starkness, where Krag was to meet them, only to find the observatory abandoned. Two bottles are found with "Solar back rays" and "Arcturian back rays". The first, when accidentally unfastened, flies back to the sun because of the light rays trapped within.

- 4 – The Voice

Nightspore leads Maskull to a spot on the shore some miles off, where they listen to The Drum Taps of Sorgie, and tells him that if he hears it again he is to "try always to hear it more and more distinctly." Maskull attempts to climb the observatory tower but is unable to go beyond the first of the seven stories because of the heavy gravity. From the first magnifying window he sees Arcturus again. He hears a voice saying that he is but an instrument and that although he will go on the voyage, only Nightspore will return.

- 5 – The Night of Departure

Nightspore says the gravity in the tower is Tormance's and that Maskull will find death on Tormance. Krag arrives, enables Maskull and Nightspore to resist Tormance's gravity by spitting on a cut in their arms, and the three climb the tower, whose windows no longer magnify. They depart naked in a 'torpedo of crystal' propelled by Arcturian back rays. During the 19-hour voyage, Maskull sleeps.

- 6 – Joiwind

Maskull awakes alone in a desert on Tormance and finds that he has new organs in his body, such as a tentacle (known as a magn) stemming from the heart and protuberances on his forehead and neck. A woman comes to him and exchanges blood with him (making it easier for him to live on Tormance, and harder for her), and says: that she is called Joiwind, her husband Panawe, and both live to the North in Poolingdred; that she understands his speech thanks to a forehead organ, the breve, that reads minds; that Surtur is called Shaping, or Crystalman, and created everything (she also implicitly says that he is God); that they do not eat, out of respect for living things, but drink gnawl water; and that the chest tentacle is used to increase love for other creatures. While journeying home they worship Shaping in a shrine, and meet Panawe upon arrival.

- 7 – Panawe

Panawe suggests that Maskull may be "a man [...] who stole something from the Maker of the universe, in order to ennoble his fellow creatures," a reference to the myth of Prometheus. He says that life on Tormance has many different forms because the planet is still new, that human beings resemble earthlings because "all creatures that resemble Shaping must of necessity resemble one another," and that Alppain is visible only to the North. Panawe tells his story to Maskull; he travelled in the Wombflash forest (from where he saw Swaylone's island), Ifdawn Marest, and Poolingdred.

- 8 – The Lusion Plain

Maskull sets out to further explore Tormance and gets to the Lusion Plain, where he meets a man, named Surtur.

Surtur asserts the beauty of his world, claims Maskull is there to serve him, and disappears. Maskull continues his journey and meets a woman, Oceaxe, from Ifdawn, who instead of a tentacle has a third arm. Although she is peremptory and rude, she shows interest in having him as lover, and gives him a red-glowing stone to convert his magn into a third arm.

- 9 – Oceaxe

When Maskull wakes up he finds his chest tentacle or magn has been transformed into the third arm, which causes lust for what is touched and his breve changed to an eyelike sorb which allows dominance of will over others. He travels through the volatile and Nietzschean landscape of Ifdawn with Oceaxe, who wants him to kill one of her husbands, Crimtyphon, and take his place. Maskull is revolted at the idea, but does kill Crimtyphon when he sees him using his will to force a man into becoming a tree.

- 10 – Tydomin

Tydomin, another wife of Crimtyphon's, shows up and uses her will to force Oceaxe to commit suicide by walking off a cliff and persuades Maskull to follow her to her home in Disscourn, where she will take possession of his body. On the way they find Joiwind's brother Digrung who says he will tell her everything; to prevent this, and encouraged by Tydomin, Maskull absorbs Digrung, leaving his empty body behind. At Tydomin's cave, he goes out of his body to, anachronistically, become the apparition of the seance where he met Krag, but when he is killed he goes back to his body before Tydomin can possess it, whereupon he awakens free of her mental power.

- 11 – On Disscourn

Maskull takes Tydomin to Sant, to kill her. In Sant no women are allowed, but only men, who go there to follow Hator's doctrine. On the way Maskull and Tydomin meet Spadevil, who proposes to reform Sant by amending Hator's teaching with the notion of duty. He turns Maskull and Tydomin into his disciples by modifying their sorbs into twin membranes called probes.

- 12 – Spadevil

Catice, the guardian of Hator's doctrine in Sant, who has only one probe, damages one of Maskull's to test Spadevil's arguments. Maskull accepts Hator's ideas and kills Spadevil and Tydomin. Catice says he will leave Sant to meditate on Spadevil's arguments, claims that Shaping is not Surtur, and sends Maskull away to the Wombflash Forest, in search of Muspel, their home.

- 13 – The Wombflash Forest

Maskull awakes in the dense Wombflash Forest with a third eye as his only foreign organ, hears the drumbeat, follows it, and meets Dreamsinter, who tells him that it was Nightspore whom Surtur brought to Tormance and that he, Maskull, is wanted to steal Muspel-light. Maskull then sees a vision in which Krag kills him while Nightspore follows a light, and faints.

- 14 – Polecrab

Maskull reawakes and proceeds to the shore of the Sinking Sea, from which Swaylone's Island can be seen. There he meets Polecrab, a simple fisherman, who is married to Gleameil.

- 15 – Swaylone's Island

Maskull goes to Swaylone's Island, where Earthrid plays a musical instrument called Irontick (actually a lake) by night, and from where no one who heard it ever returned. Maskull is accompanied by Gleameil, who has left her family because of the attraction of the music. Earthrid warns Gleameil that the music he plays will kill her, but she stays and promptly dies. Maskull, after entering a trance, forcibly plays the lake, whereupon Earthrid dies, violently dismembered, and Irontick is destroyed.

- 16 – Leehallfae

Maskull crosses the sea by manoeuvring a many-eyed, heliotropic tree and reaches Matterplay, where much to his amazement a plethora of life-forms alongside a magical creek materialise and vanish before his eyes. He goes upstream and meets Leehallfae, an immensely old being ("phaen") who is neither man nor woman, but of a third sex, who has been seeking the underground country of Threal for eons, where ae [sic] believes a god called Faceny (which may be another name for Shaping) is to be found.

- 17 – Corpang

They reach Threal by entering a cave. Leehallfae promptly falls ill and dies. Corpang appears and says this is because Threal is not Faceny's world, but Thire's. Faceny, Amfuse, and Thire are the creators of three worlds of existence, relation, and feeling. Corpang has come to Threal to follow Thire, and leads Maskull to three statues of these divinities. There Maskull has a vision of their power, and hears a voice saying he is to die in a few hours, after which the statues are seen with faces like a corpse's, showing that they are merely disguises for Shaping/Crystalman. Realising that he has been worshipping false gods, Corpang follows Maskull to Lichstorm, where they hear the drumbeats.

- 18 – Haunte

Maskull and Corpang meet Haunte, a hunter who travels in a boat that flies thanks to masculine stones which repel earth's femininity. After Maskull destroys the masculine rocks which protected Haunte from Sullenbode's femininity, all three journey to her cave. Sullenbode, a faceless woman, kills Haunte as they kiss.

- 19 – Sullenbode

Maskull desires Sullenbode and she desires him, thereby becoming alive (without killing him) as long as he loves her. Maskull, Sullenbode and Corpang proceed in the direction someone looking for Muspel once went. As they near their destination, Corpang goes eagerly ahead but Maskull stops, caught in a vision of Muspel-light. His momentary loss of interest and her inability to recall him from his trance causes Sullenbode to die. As the vision fades Maskull discovers Sullenbode and, leaving Corpangs path, proceeds down the mountain to bury Sullenbode.

- 20 – Barey

Maskull, upon waking, discovers Krag again, and then Gangnet, who defends Shaping and his creation. Since Gangnet is unable to send the abusive Krag away, they travel together to the ocean and then take to the sea on a raft. When the sun Alppain rises, Maskull sees in a vision Krag causing the drum beat by beating his heart, and Gangnet, who is Shaping, dying in torment enveloped by Muspel-fire. Back on the raft, Krag tells Maskull that he (Maskull) is Nightspore; then Maskull dies.

- 21 – Muspel

Krag and Nightspore arrive at Muspel, where there is a tower similar to that in Starkness (the observatory in Scotland). From the windows of its several stories Nightspore sees that Shaping (the Gnostic demiurge) uses what comes from Muspel to create the world in order that he may feel joy, fragmenting the Muspel matter in the process and producing suffering for all living things. Krag acknowledges that he is Surtur and is known on Earth as pain. Nightspore goes back with him to reincarnate and spread knowledge about Surtur, Shaping, and Muspel.

Setting

Geography

The story is set on Tormance, an imaginary planet orbiting the star Arcturus, which, in the novel (but not in reality) is a double star system, consisting of Branchspell, a large yellow sunlike star, and Alppain, a smaller blue star. It is said in the novel to be 100 light-years distant from Earth.

There is no systematic description of the geography of Tormance; Maskull simply travels from South to North (with a somewhat eastward excursion to the Sant levels). The direction is symbolic: the light of the second sun, Alppain, is seen to the north; the southern countries are illuminated only by Branchspell. Maskull travels always in the direction that puts behind him earthly sights and things, seeking the other world illuminated by Alppain.

Names

The historian Shimon de Valencia states that the names "Surtur" and "Muspel" are taken from Surtr, the lord of Múspellsheimr (the world of fire) in Norse mythology.[8]

Lindsay's choice of title (and therefore the setting in Arcturus) may have been influenced by the nonfictional A Voyage to the Arctic in the Whaler Aurora (1911), published by his namesake, David Moore Lindsay.[9]

Inventions

The novel is recognised for its strangeness.[5] Among the many features of the world of Tormance are its alien sea, with water so dense that it can be walked on, while gnawl water is sufficient food to sustain life on its own. The local spectrum includes two primary colours, ulfire and jale, unknown on Earth, as well as a third colour, dolm, said to be compounded of ulfire and blue. (Lindsay writes: '[t]he sense impressions caused in Maskull by these two additional primary colours can only be vaguely hinted at by analogy. Just as blue is delicate and mysterious, yellow clear and unsubtle, and red sanguine and passionate, so he felt ulfire to be wild and painful, and jale dreamlike, feverish, and voluptuous.'[10]) Tormance people are able to speak to people from Earth, as their ability to read thoughts enables them to understand both meaning and words. The planet itself is entirely un-Earthlike with unique life-forms, such as three-legged animals that spin, and a ten-finned flying animal.

The sexuality of the Tormance species is ambiguous; Lindsay coined a new gender-specific pronoun series, ae, aer, and aerself for the phaen who are humanoid but formed of air. The character Panawe who briefly guides Maskull was born male and female, but becomes male when his female component relinquishes life to allow him to live as a male. Maskull himself acquires Tormance organs which give him additional senses including telepathy; these include a tentacle on his chest and a fleshy organ on his forehead that changes into a third eye.

Effect

Influence

The novel was a central influence on C. S. Lewis's 1938–1945 Space Trilogy.[2] Lewis also mentioned the "sorbing" (aggressive absorption of another's personality into one's own, fatal to the other person) as an influence on his 1942 book The Screwtape Letters.[11] Lewis in turn recommended the book to J. R. R. Tolkien, who said he read it "with avidity", finding it more powerful, more mythical but less of a story than Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet; he commented that "no one could read it merely as a thriller and without interest in philosophy[,] religion[,] and morals".[3][5]

In 1984, the composer John Ogdon wrote an oratorio for soprano, mezzosoprano, tenor, and baritone accompanied by choir and piano entitled, A Voyage to Arcturus. He based the oratorio on Lindsay's novel and "biblical quotations". Ogdon's biographer, Charles Beauclerk, notes that Lindsay was also a composer, and that the novel discusses the "nature and meaning" of music. In Beauclerk's view, Ogdon saw Linday's novel as a religious work, where for instance the wild 3-eyed, 3-armed woman Oceaxe becomes Oceania, described in the Bible's Book of Revelation 12 as "a woman cloth'd with the sun, and the moon under her feet".[9]

Reception

The critic and philosopher Colin Wilson described A Voyage to Arcturus as the "greatest novel of the twentieth century".[1] Clive Barker stated that "A Voyage to Arcturus is a masterpiece" and called it "an extraordinary work . . . quite magnificent."[4] Philip Pullman named it for The Guardian as the book he thought was most underrated.[12]

Reviewing the book in 2002, the novelist Michael Moorcock asserted that "Few English novels have been as eccentric or, ultimately, as influential". He noted that Alan Moore, introducing the 2002 edition, had compared the book to John Bunyan (Pilgrim's Progress, 1678) and Arthur Machen (The Great God Pan, 1890), but that it nevertheless stood "as one of the great originals". In Moorcock's view, although Maskull seems to be commanded to do whatever is needed to save his soul, in a kind of "Nietzschean Pilgrim's Progress", Lindsay does not fall into fascism. Like Hitler, Moorcock argued, Lindsay was traumatised by the trench fighting of the First World War, but the "astonishing and dramatic ambiguity of the novel's resolution" makes the novel the antithesis of Hitler's "visionary brutalism". Moorcock noted that while the book had influenced C. S. Lewis's science fiction trilogy, Lewis had "refused Lindsay's commitment to the Absolute and lacked his God-questioning genius, the very qualities which give this strange book its compelling, almost mesmerising influence."[5]

Also in 2002, Steven H. Silver, criticising A Voyage to Arcturus on SF Site, observes that for a novel it has little plot or characterisation, and furthermore that it gives no motives for the actions taken by its characters. In his view, the book's strength lies in its "philosophical musings" on humanity after the First World War. Silver compares the book not with later science fiction but with that of H. G. Wells and Jules Verne, "although with neither author's prose skills." He suggests that Lindsay was combining philosophy with an adventure tale in the manner of Edgar Rice Burroughs.[13]

Publication history

Methuen agreed to publish the novel, but only if Lindsay agreed to cut 15,000 words, which he did. These passages are assumed lost forever. Methuen also insisted on a change of title, from Lindsay's original (Nightspore in Tormance), as it was considered too obscure.[14] But out of an original press run of 1430 copies, no more than 596 were sold in total.[15] A Voyage to Arcturus was made widely available in paperback form when published as one of the precursor volumes to the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in 1968, featuring a cover by illustrator Bob Pepper.[16]

Editions of A Voyage to Arcturus have been published in 1920 (Methuen), 1946 (Gollancz), 1963 (Gollancz, Macmillan, Ballantine), 1968 (Gollancz, Ballantine),1971 (Gollancz), 1972, 1973, 1974 (Ballantine), 1978 (Gollancz), 1992 (Canongate), 2002 (Univ. Nebraska), and later by several publishers.[17]

The book has been translated into Bulgarian, Catalan, Dutch, French, German, Japanese, Polish, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Spanish, and Turkish.[6][18][19]

Adaptations and sequels by others

The BBC Third Programme presented a radio dramatisation of the novel in 1956.[20] Critic Harold Bloom, in his only attempt at fiction writing, wrote a sequel to this novel, entitled The Flight to Lucifer.[21] Bloom has since critiqued the book as a poor continuation of the narrative.[22] William J. Holloway, then a student at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio created a 71-minute film adaptation of the novel in 1970.[23] The film, unavailable for many years, was independently restored, re-edited and color-enhanced,[24] to be redistributed on DVD-R in 2005.[25] In 1985, a three-hour play by David Wolpe based on the novel was staged in Los Angeles.[26] Paul Corfield Godfrey wrote an operatic setting based on the novel to a libretto by Richard Charles Rose and this was performed at the Sherman Theatre Cardiff in 1983.[27] The jazz composer Ron Thomas recorded a concept album inspired by the novel in 2001 entitled Scenes from A Voyage to Arcturus.[28] Music from the album is featured in the 2005 restoration of the 1970 student film. Ukrainian house producer Vakula (Mikhaylo Vityk) released an imaginary soundtrack called A Voyage To Arcturus as a triple LP in 2015.[29] The first musical based on the novel, by Phil Moore, was performed in 2019 at the Peninsula Theatre, Woy Woy, Australia.[30][31]

See also

References

- Kieniewicz, Paul M. (2003). "Book Review: A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay". Archived from the original on 15 December 2014.

- Lindskoog, Kathryn. "A Voyage to Arcturus, C. S. Lewis, and The Dark Tower". Discovery.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). "Letter to Stanley Unwin, 4 March 1938". The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. London: George Allen and Unwin. ISBN 0-618-05699-8.

- A Voyage to Arcturus. Savoy Books.

- Moorcock, Michael (31 August 2002). "A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay". The Guardian.

- "The Life and Works of David Lindsay". VioletApple. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- David Lindsay, by Gary K. Wolfe

- de Valencia, Shimon (18 April 2017). "A Voyage to Arcturus A fresh look at the first and possibly greatest work of Scottish author, David Lindsay". Omnitopian Thoughts. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Beauclerk, Charles (2014). Piano Man: Life of John Ogdon. Simon and Schuster. pp. 333–334. ISBN 978-0-85720-011-2.

- A Voyage to Arcturus by David Lindsay.

- Lewis, C. S. (1961) [1942]. The Screwtape Letters. p. xiii, "Preface to the Paperback Edition". ISBN 0-02-086860-X.

- Pullman, Philip (29 September 2017). "Philip Pullman: 'The book I wish I'd written? My next one'". The Guardian.

- Silver, Steven H. "A Voyage to Arcturus David Lindsay". SF Site. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Sellin, Bernard, The Life & Works of David Lindsay (Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 22.

- Gary K. Wolfe (1982). David Lindsay. Wildside Press LLC. ISBN 978-0-916732-26-4.

- "The art of Bob Pepper", on John Coulthart's feuilleton, 12 July 2007.

- "A Voyage to Arcturus". WorldCat. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Lindsay, David. "Podróż na Arktura". sf.giang.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- Lindzi, Dejvid. "Putovanje na Arktur". Carobnaknjiga (in Serbian). Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "Howard Marion-Crawford, Stephen Murray in 'A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS'". BBC Genome Project. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- David Fite (1 June 2009). Harold Bloom: The Rhetoric of Romantic Vision. Univ of Massachusetts Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-55849-753-5.

- Joseph R. Millichap (2009). Robert Penn Warren After Audubon: The Work of Aging and the Quest for Transcendence in His Later Poetry. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-8071-3671-3.

- "William Holloway's Film of A Voyage to Arcturus". The Violet Apple.org.uk. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Got the Distance, archived from the original on 12 March 2005

- Custom Flix

- "'A Voyage to Arcturus': A Journey to an Enigma" by Sylvie Drake, Los Angeles Times, 2 October 1985.

- "Opening Night! Opera & Oratorio Premieres | Arcturus". Stanford University Libraries | Operadata. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Ron Thomas, archived from the original on 4 May 2005.

- Coultate, Aaron (17 October 2014). "Vakula goes on A Voyage To Arcturus". Resident Advisor. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- "A Voyage to Arcturus: The Heavy-Metal Steampunk Sci-Fi Musical". Arcturus Musical. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "Theatre: A Voyage to Arcturus". Phil Moore. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Lindsay, David. A Voyage to Arcturus. Internet Archive (audiobooks).

- Lindsay, David. "A Voyage to Arcturus". Project Gutenberg. (plain text and HTML)

- Lindsay, David. A Voyage to Arcturus. The Violet Apple: The Life and Work of David Lindsay.

A Voyage to Arcturus public domain audiobook at LibriVox

A Voyage to Arcturus public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Names in A Voyage to Arcturus on VioletApple: The Life and Works of David Lindsay