Abe Lincoln in Illinois (play)

Abe Lincoln in Illinois is a play written by the American playwright Robert E. Sherwood in 1938. The play, in three acts, covers the life of President Abraham Lincoln from his childhood through his final speech in Illinois before he left for Washington. The play also covers his romance with Mary Todd and his debates with Stephen A. Douglas, and uses Lincoln's own words in some scenes. Sherwood received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1939 for his work.

| Abe Lincoln in Illinois | |

|---|---|

Raymond Massey in Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1938) | |

| Written by | Robert E. Sherwood |

| Characters | |

| Date premiered | October 15, 1938 |

| Place premiered | Plymouth Theatre, New York City |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | Historical drama |

| Setting | Illinois |

Productions

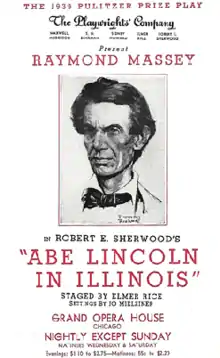

The play premiered on Broadway on October 15, 1938, at the Plymouth Theatre and closed in December 1939 after 472 performances. Directed by Elmer Rice, it starred Raymond Massey as Lincoln, Muriel Kirkland (Mary Todd), Adele Longmire (Ann Rutledge), and Albert Phillips (Stephen A. Douglas).[1] It subsequently transferred to the Grand Opera House in Chicago where it ran for 12 weeks from January 8 through March 30, 1940.[2] Massey's role in the play came about as the result of a promise he had made to Sherwood six years previously to "be there when he needed me".[3] It was the first production of the newly established Playwrights' Company.[4]

The play has twice been revived on stage. In 1963 Hal Holbrook starred as Lincoln in an off-Broadway revival at the Phoenix Theatre.[4] A second revival took place in 1993 at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre, with Sam Waterston as Lincoln, and direction by Gerald Gutierrez. The cast included Marissa Chibas (Ann Rutledge), David Huddleston (Judge Bowling Green), Robert Joy (Joshua Speed), Lizbeth MacKay (Mary Todd) and Brian Reddy (Stephen A. Douglas).[5] The revival ran from November 29, 1993, to January 2, 1994.[6]

Overview and synopsis

The play takes place in and around New Salem, Illinois, in the 1830s, then in Springfield, Illinois, in the 1840s, and in Act III in Springfield in 1858 to 1861. It is based principally on the 1926 biography Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years by Carl Sandburg, which covers Lincoln's life up to his inauguration as President. The play depicts Lincoln's evolution from unambitious backwoodsman to a champion of freedom, and relies on the audience's knowledge of Lincoln's subsequent career to color the portrayal of his character.[7] Sherwood wrote the play as a riposte to isolationist sentiment in the United States in the lead-up to the Second World War; he had fought in the First World War but had been disappointed by the way the post-war world had turned out.[8] The play emphasizes the need to overcome laissez-faire sentiment and to stand up and take firm political action for the public good.[8] As its star Raymond Massey put it, "If you substitute the word dictatorship for the word slavery throughout Sherwood's script, it becomes electric with meaning for our time."[9]

While much of the dialog is of Sherwood's invention, the play uses some of Lincoln's own words at various points. Lincoln is portrayed not as a saint or a fount of wisdom, but as a humble man of ideas who constantly questions himself and his ability to make a difference. He is haunted by premonitions of death and disaster, prefiguring the bloodshed of the American Civil War and his own assassination. Ann Rutledge, the first great love of his life, is portrayed as Lincoln sees her, as a selfless but ultimately unattainable embodiment of female perfection. His wife Mary, by contrast, is portrayed with an increasingly sharp edge that foreshadows her descent into insanity. Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln's political opponent in 1858, is portrayed as an adept politician rather than as a villain.[10]

Act I

The opening scene of the play depicts New Salem's schoolmaster teaching grammar to Lincoln and encouraging him to appreciate poetry and oratory. Lincoln speaks of his life, referring to his failures as a businessman, his fear of city people and the death of his mother, and expresses his appreciation of John Keats's poem On Death.[7]

In Scene 2, Lincoln meets a number of young politicians at the Rutledge Tavern in New Salem to explore the possibility of him running for the Illinois General Assembly. By now he is serving as the local postmaster. He convinces them that he would make a good candidate and notes that the pay would help him clear his debts. When the politicians leave he talks with the tavern-keeper's daughter, Ann Rutledge, and declares his love for her. Ann appears receptive and he declares his intention to run for the assembly.[7]

A year later, Scene 3 sees his friends discussing Lincoln's relative lack of success in his career as an assemblyman and his unrequited romance with Ann, which they feel is a hindrance. He bursts in, announces that Ann has just died, and declares that he has to "die and be with her again, or I'll go crazy!"[7]

Act II

Scene 4 opens five years later with Lincoln now a 31-year-old lawyer in Springfield. He has been aged greatly by the stress of Ann's death, but has been more successful in his career and has managed to pay off some of his debt. He is opposed to slavery but rejects the cause of the Abolitionists, who he regards as "a pack of hell-roaring fanatics". Lincoln's friends urge him to re-enter politics but he disclaims any desire to "get down into the blood-soaked arena and grapple with all the lions of injustice and oppression". In a bit to shake him out of his lethargy, a friend introduces him to Mary Todd, the daughter of the president of the Bank of Kentucky.[7]

Half a year has passed by the time of Scene 5, when the ambitious Mary decides that she will marry Lincoln. Her sister criticises her decision, calling him a "lazy and shiftless" boor. Mary defends Lincoln, saying that she wants to shape a new life for the couple.[11]

The wedding is set to take place in Scene 6 but Lincoln has developed cold feet. A friend tries to persuade him not to cancel it, and Mary's brother-in-law advises him to "keep a tight rein" on her ambition for him to become President. Lincoln's clerk applauds his betrothal to someone who will push him to fight for the freedom of the slaves. Lincoln himself decides that his ambitions lie elsewhere, cancels the wedding and leaves Springfield.[11]

In Scene 7, Lincoln meets a friend who is heading west and is confronted by the fact that the infamous decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford has effectively extended slavery there as well. The friend, who is travelling with a free black companion, says that he will go to Canada or establish a new free country if his companion and other black people cannot be free in the United States. Lincoln realises that the country is in peril and urges his friend not to give up. He prays for help from God and urges the Almighty to grant his friend's child and all men their birthrights.[11]

Lincoln heads back to Springfield in Scene 8 and meets again with Mary Todd. He appeals to her to marry him, telling her, "The way I must go is the way you have always wanted me to go." He promises to devote the rest of his life to doing "what is right." Mary falls into his arms and declares that she loves him eternally.[11]

Act III

Scene 9 opens with Lincoln and his rival senatorial candidate Stephen A. Douglas making opposing speeches on slavery in an Illinois town during the 1858 campaign for the U.S. Senate.[11]

Jumping to 1860 in Scene 10, Lincoln and Mary sit in the parlor of their house with their boys, awaiting the arrival of senior politicians intent on sounding him out for the Republican Party's presidential nomination. Mary is angered by her eldest son's habit of smoking in the house and Lincoln's failure to tell her about the politicians' visit, though she recognizes the burden of her growing irritability, which prefigures her eventual insanity. The visitors conclude that in his "curious, primitive way," Lincoln could be a winning presidential candidate.[12]

The 1860 presidential election is the focus of Scene 11, in which Lincoln and Mary await the election results. By now they are quarreling openly. She tells him that even if he wins, "it's ruined, for me. It's too late." Lincoln does win but regrets having had to fight "the dirtiest campaign in the history of corrupt politics." As he leaves home with a Secret Service escort, he feels the full weight of his responsibilities.[12]

The play concludes in Scene 12 with Lincoln preparing to depart from Springfield's railroad station (the present Lincoln Depot) and go to Washington, D.C. for his inauguration. His Secret Service bodyguards worry about protecting him in the face of the many death threats he has received even before taking office. Lincoln appears before a crowd and gives a farewell address. As the train pulls out, the crowd sings (anachronistically), "His soul goes marching on."[12]

Adaptations

The play was adapted into a film, also called Abe Lincoln in Illinois, which was released in 1940 and was directed by John Cromwell. When Sherwood agreed to sell the film rights, he added a condition that Massey was to be given the starring role. After receiving an Oscar nomination for the film, Massey went on to portray Lincoln twice more in films and in two television adaptations, leading him to complain jokingly that he was "the only actor ever typecast as a president."[3] There were six television adaptations in all, in 1945, 1950, 1951, 1957, 1963 and 1964. Massey reprised his stage role in the 1950 and 1951 adaptations. The 1964 production in the Hallmark Hall of Fame series featured Jason Robards in the title role, and Kate Reid as Mary Todd.[13]

Critical response

The play was critically acclaimed for its original 1938 run. The Herald Tribune's reviewer, Richard Watts Jr., called it "Not only the finest of modern stage biographies, but a lovely, eloquent, endearing tribute to all that is best in the spirit of democracy."[4] Burns Mantle of the New York Daily News called it "biographical drama with a soul", while Richard Lockridge of the New York Evening Sun described it as "a satisfying and deeply impressive play."[14] The critic Brooks Atkinson called it Sherwood's "finest play" and commended it for furthering "the principles of American liberty" while still providing an honest presentation of Lincoln's formative years.[15] It was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1939 by a majority vote of the prize jury, with the supporting jurors describing it as "a competent play by an experienced dramatist, with the chief figure movingly presented, with the minor characters done adequately and adroitly."[16] Many critics highlighted Massey's performance for praise; his preparation was so meticulous and obsessive that the critic George S. Kaufman suggested that he would not be satisfied until he was assassinated.[17]

The 1993 revival was less positively received than its predecessors. The original had been seen as ground-breaking and complex, but by 1990s standards it was viewed as too long and outdated. Some critics praised its sweep and Sam Waterston's performance, but others, like David Richards of The New York Times, felt it was too "didactic or melodramatic".[15] He wrote, "'Abe Lincoln in Illinois' is an endeavor of daunting dimensions....for all its loftiness of purpose and the generosity of Lincoln's own words, some of which are incorporated into the script, Sherwood's dramaturgy seems dismayingly earthbound today. When the dialogue is not clumsy... it smacks of simple-mindedness... When Lincoln finds his life's purpose and steels himself for the ordeals to come, Mr. Waterston is able to suggest great stature simply by standing tall and motionless.[18] Linda Winer suggested that the TV miniseries had taken over as audiences' preferred format for such historical or biographical dramas.[15]

Awards and nominations

- 1939 Pulitzer Prize for Drama[19]

- 1994 Drama Desk Award Outstanding Play Revival nominee

- 1994 Drama Desk Award, Outstanding Actor in a Play (Waterston) nominee

- 1994 Tony Award for Best Revival of a Play nominee

- 1994 Tony Award, Best Actor in Play (Waterston) nominee

- 1994 Tony Award, Best Direction of a Play (Gerald Gutierrez) nominee

References

- "'Abe Lincoln in Illinois' 1938" playbillvault.com, accessed December 22, 2015

- Chicago Stagebill Yearbook. Chicago Stagebill. 1947. p. 222.

- Foster, Charles (2003). Once Upon a Time in Paradise: Canadians in the Golden Age of Hollywood. Dundurn. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-55002-997-0.

- Bordman, Gerald; Hischak, Thomas S. (2004). The Oxford Companion to American Theatre. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-516986-7.

- "'Abe Lincoln in Illinois' 1993" Archived December 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine playbillvault.com, accessed December 22, 2015

- "Abe Lincoln in Illinois 1993" Internet Broadway Database, accessed September 5, 2011

- Matlaw, Myron (1972). Modern World Drama: An Encyclopedia. Secker & Warburg. p. 1. ISBN 0436274353.

- Simon, John (13 December 1993). "Lincoln Mercurial". New York Magazine. p. 108.

- Kaufman, Will (2006). Civil War in American Culture. Edinburgh University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7486-2656-4.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2017). 100 Greatest American Plays. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4422-5606-4.

- Matlaw, p. 2

- Matlaw, p. 3

- Reinhart, Mark S. (2009). Abraham Lincoln on Screen: Fictional and Documentary Portrayals on Film and Television. McFarland. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-0-7864-5261-3.

- Hischak (2017), p. 4

- Matviko, John W. (2005). The American President in Popular Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-313-32705-6.

- Fischer, Heinz-Dietrich (2013). Outstanding Broadway Dramas and Comedies: Pulitzer Prize Winning Theater Productions. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 48. ISBN 978-3-643-90341-9.

- Hischak (2017), p. 5

- Richards, David (November 30, 1993). "Review/Theater: Abe Lincoln in Illinois; Lincoln as Metaphor For a Big Job Ahead, In 1939 and Today". The New York Times. Retrieved May 13, 2017.

- "Pulitzer Prize for Drama" pulitzer.org, accessed December 22, 2015