Abigail Adams Smith

Abigail "Nabby" Amelia Adams Smith (July 14, 1765 – August 15, 1813) was the daughter of Abigail and John Adams, founding father and second President of the United States, and the sister of John Quincy Adams, sixth President of the United States. She was named for her mother.[1]

Abigail "Nabby" Adams Smith | |

|---|---|

portrait by Mather Brown | |

| Born | July 14, 1765 |

| Died | August 15, 1813 (aged 48) Quincy, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hancock Cemetery in Quincy, Massachusetts |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent(s) | John Adams Abigail Smith |

| Family | Adams, Quincy |

Romance and marriage

At the age of 18, Nabby met and fell in love with Royall Tyler. Her father thought she was too young to have a suitor, but he eventually accepted it. At one point the two were even engaged to be married. But John Adams, then the U.S. minister to the Kingdom of Great Britain, eagerly called for his wife and daughter to join him in London. For a time, Nabby maintained a long-distance relationship with Tyler, but eventually broke off the engagement, leaving Tyler depressed.[2]

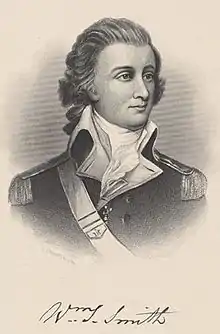

Shortly afterward Nabby met Colonel William Stephens Smith, who was serving as her father's secretary and was 10 years her senior. They would later be related by marriage—Col. Smith's sister was the wife of Nabby's brother Charles Adams (1770–1800). They were married at the American minister's residence in London on June 12, 1786.[3] Nabby's observations of European life and customs, and of many of the distinguished statesmen of the day, were later published.[4]

Their courtship was thought to be too short by Nabby's parents, and historians have not considered it to be a good marriage. While Colonel Smith was kind to his family, he never settled, continually seeking a better lot in life. He spent more money than he earned and lost everything to real estate speculation in the early 1800s. This left them on a small farm along the Chenango River in central New York.[5]

Their children were:

- William Steuben Smith

- John Adams Smith

- Thomas Hollis Smith

- Caroline Amelia Smith; married John Peter DeWint of Fishkill-on-Hudson.

Diagnosis of breast cancer

In 1810, Nabby was diagnosed with breast cancer. On October 8, 1811, a mastectomy was performed by John Warren.[6] The operation was performed by Warren and several assistants without any anesthesia in an upstairs room of the Adams home. Her mother, husband, and daughter, Caroline, were also on hand to assist.

The surgery

The exact details of the surgery are not known but it was described as a typical 19th century operation. The instruments used during the surgery consisted of a large fork with a pair of six-inch prongs sharpened to a needle point, a wooden-handled razor, a small oven filled with heated coals, and a thick iron spatula. Before the surgery began Dr. Warren strapped "Nabby" into a chair to restrain her, and then began to remove the clothing to expose the area on which he would operate. Once the diseased breast was exposed, other physicians held her left arm back so that Dr. Warren would have better access to the diseased tissue. He began the surgery by thrusting the large fork into her breast and lifting it from the chest wall. He then sliced at the base of the breast until it was completely severed from her chest. After removing the breast, he saw that the cancer had spread to the lymph nodes under Abigail's arms, and he worked to remove those tumors as well. To stop Abigail's bleeding, Dr. Warren applied the heated spatula to cauterize the open cuts, and then sutured the wounds. The surgery took around 25 minutes, but dressing the wounds took more than an hour.[6] Warren and his assistants later expressed astonishment that Abigail endured the pain of the surgery and cauterization without crying out, despite the gruesomeness of the operation, which was so horrifying it caused her mother, husband, and daughter to turn away.

Death

About seven months after the surgery, in 1812, Abigail finally started to feel well once more. So she then returned home to New York where she subsequently began feeling pain in her abdomen and spine, as well as suffering from painful headaches. At first a local doctor in New York said that the pain was from rheumatism, but later in 1813 new tumors began to appear in the scar tissue as well as on the skin. She then returned to her parents' house to die; she died in August 1813 at the age of 48.[2][5][6][7][lower-alpha 1] She was buried at Hancock Cemetery in Quincy.

Depictions in popular culture

Nabby's death is a poignant part of the 2008 John Adams miniseries, in which she is played by Sarah Polley; Nabby Adams as a young girl was played by Madeline Taylor in the first three episodes of the same series. The series took artistic license by shifting Abigail's cancer diagnosis to 1803, and changing many other aspects of her life.[9]

Mount Vernon Hotel Museum and Garden

The Abigail Adams Smith Museum, now known as the Mount Vernon Hotel Museum and Garden, was a carriage house was built in 1799 by a wealthy New York china merchant on property purchased from Abigail and her husband Col. William Stephens Smith. The carriage house was purchased by Joseph Hart and converted into a day hotel. Day hotels were popular at the time as they provided the burgeoning New York middle class an escape from the overcrowded and oppressive city. It was called the Mount Vernon Hotel after George Washington's home in Virginia and functioned in this capacity from 1826 to 1833. The property changed hands again when it was purchased by Jeremiah Towle. It served as the Towle family's private residence until 1905 when, with the spread of industrialization, it was purchased by Standard Gas Light Company. The building was preserved until its ultimate purchase by the Colonial Dames of America in 1924. In 1939, the building was opened to the public as the Abigail Adams Smith Museum. The Colonial Dames of America reinterpreted the house as a day hotel and reopened it as the Mount Vernon Hotel Museum and Garden in 2000. It remains open to the public with museum tours daily (except Monday).[10]

Family tree

Notes

- Sources identify Smith's specific date of death as August 9, 14, or 15. August 15 is almost certainly correct. The earliest newspaper accounts of Smith's passing appeared on August 16. The death notice in the Independent Chronicle (Boston, MA) for Monday, August 16, 1813 specified that Smith died "yesterday" and that the funeral would be held "tomorrow".[8]

References

- (2006) American Experience: John and Abigail Adams. PBS Paramount.

- "Royall Tyler, the Man Nabby Adams Wanted To Marry". New England Historical Society. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Nagel, Paul C. 1987. The Adams women: Abigail and Louisa Adams, their sisters and daughters. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503874-6

- Smith, Abigail Adams 1841. Journal and correspondence of Miss Adams, daughter of John Adams, second president of the United States, written in France and England, in 1785. book

- Olson, James S. (2002). "Jim Olson's Essay on Abigail Adams". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- "Abigail Adams Smith | History of American Women". History of American Women Blog. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- Adams, John (1854). "To Thomas Jefferson". The Works of John Adams, vol. 10 (Letters 1811–1825, Indexes). Retrieved June 28, 2018.

16 August, 1813 ... my only daughter, expired yesterday morning

- "Death Notice, Mrs. Abigail Smith". Independent Chronicle. Boston, MA. August 16, 1813. p. 3 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- Jeremy Stern (October 27, 2008). "What's Wrong with HBO's Dramatization of John Adams's Story". History News Network. Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- "The 1799 Mount Vernon Hotel - 421 E. 61st Street". November 4, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2018.

External links

- Nagel, Paul. The Adams Women: Abigail and Louisa Adams, Their Sisters and Daughters. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

- The Adams Children

- American Experience-John And Abigail Adams

- Adams family biographies – Massachusetts Historical Society

- Olson, James. Essays about Abigail "Nabby" Adams from book, Bathsheba's Breast: Women, Cancer & History. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.