Aboyne

Aboyne (Scots: Abyne, Scottish Gaelic: Abèidh) is a village on the edge of the Highlands in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, on the River Dee, approximately 26 miles (42 km) west of Aberdeen. It has a swimming pool at Aboyne Academy, all-weather tennis courts, a bowling green and is home to the oldest 18 hole golf course on Royal Deeside. Aboyne Castle and the Loch of Aboyne are nearby.

Aboyne

| |

|---|---|

The Green in Aboyne | |

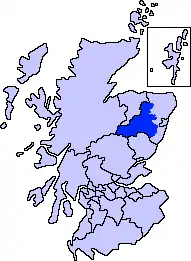

Aboyne Location within Aberdeenshire | |

| Population | 2,910 (mid-2016 est.)[4] |

| OS grid reference | NO527986 |

| • Edinburgh | 79 mi (127 km) |

| • London | 399 mi (642 km) |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | ABOYNE |

| Postcode district | AB34 |

| Dialling code | 013398 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Aboyne has many businesses, including a supermarket (Co-op),[5] one bank, several hairdressers, a butcher, a newsagent, an Indian restaurant and a post office. Originally, there was a railway station in the village, but it was closed on 18 June 1966. The station now contains some shops and the tunnel running under the village is now home to a firearms club. The market-day in Aboyne was known as Fèill Mhìcheil (Scottish Gaelic for "Michael's Fair").

History

The name “Aboyne” is derived from “Oboyne”, first recorded in 1260, in turn derived from the Gaelic words “abh”, “bo”, and “fionn”, meaning “[place by] white cow river”.[6]

The village of Aboyne was founded by Charles Gordon, 1st Earl of Aboyne in 1671, who, in the same year, rebuilt the west wing of Aboyne Castle.[7] The siting of the castle itself is related to the limited number of the crossings of the Mounth of the Grampian Mountains to the south.[8] In 1715 Aboyne was the scene of a tinchal, or great hunt, organised by John Erskine, sixth Earl of Mar, on 3 September, as a cover for the gathering of Jacobite nobles and lairds to discuss a planned Jacobite rising. The uprising began three days later in Braemar.[9]

Religion

An eighth-century Christian presence in Aboyne is attested by a Pictish stone cross called the Formaston Stone. The slab is also inscribed with Ogham characters which have been transliterated as “MAQQOoiTALLUORRH | NxHHTVROBBACCxNNEVV.”[10] These are the Pictish names Talorc (TALLUORRH) and Nehht (NxHHT), both of which were names of kings.[11] In fact, the Pictish king Nechtan (d. 732) was said by Bede to have accepted the Christian faith in response to the teachings of Adamnan, abbot of Iona, eventually bringing his people to Christianity as well.[12] Aboyne’s first church was dedicated to Adamnan, and it was at the burial ground of this church where the Formaston Stone was first discovered. The stone was eventually removed to Aboyne Castle and is currently exhibited in the Inverurie Museum.[13]

In 1237, Alexander II granted the Knights Templar a charter of liberty to acquire lands in Scotland, and Walter Byset, Lord of Aboyne, gave the Templar preceptory the church of Aboyne.[14] Then, between 1239 and 1249, the church was conveyed to the Templars adproprier usus by Ralph, Bishop of Aberdeen. According to the terms of the charter, the Templars would take charge of the temporalities of the church and maintain a vicar there, while the bishop retained authority in spiritual matters. King Alexander II confirmed the donation on April 15, 1242, and Pope Alexander IV, in 1277, the same year that John of Annan, chaplain to Alexander III, was appointed vicar. Aboyne, along with other Templar possessions in Scotland, was held by the Torphichen Preceptory in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and remained so until the Reformation.[15]

In 1761, a new parish church was constructed in Aboyne; then, in 1842, another church was built on the site of the eighteenth-century structure, and in 1929 at the Union of the Established Church, it was formally dedicated to St. Machar. In 1936, St. Machar’s was joined with the United Free Church, and fifty years later, was linked with the parish church of Dinnet, a linkage which led to the 1993 union between the two, which is now known as the Aboyne-Dinnet Parish Church. In 2006, Aboyne-Dinnet was linked with the parish church at Cromar.[16]

Climate

Aboyne has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb), similar to most of the United Kingdom. Due to its high inland position in Scotland, Aboyne can record some very low temperatures and some high snowfall. Conversely, temperatures can reach exceptional values for the latitude, particularly during the winter months due to the foehn effect; it holds the January and March record for the highest temperatures in Scotland, with 18.3 °C (64.9 °F) on 26 January 2003 and 23.6 °C (74.5 °F) on 27 March 2012. The former is also the UK's highest January temperature on record, which it shares with Inchmarlo, Kincardineshire and Aber, Gwynedd. The February record for Scotland was broken on 21 February 2019 at 18.3 °C.[17]

| Climate data for Aboyne (140 m or 459 ft asl, averages 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.3 (64.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.4 (83.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

29.7 (85.5) |

28.5 (83.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

31.6 (88.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.2 (−9.8) |

−21.4 (−6.5) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−23.2 (−9.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 66.2 (2.61) |

48.5 (1.91) |

53.6 (2.11) |

56.0 (2.20) |

59.1 (2.33) |

55.6 (2.19) |

67.9 (2.67) |

60.8 (2.39) |

68.0 (2.68) |

92.7 (3.65) |

84.8 (3.34) |

66.9 (2.63) |

780.0 (30.71) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 12.8 | 10.7 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 9.2 | 12.9 | 12.6 | 11.6 | 133.7 |

| Source: Met Office[18] | |||||||||||||

Tourism and culture

.jpg.webp)

In summer, when tourists visit, the number of people and vehicles increases dramatically. The Highland Games on the Village Green features in August. Aboyne is unusual in having The Green on which events are held, as the village was modelled by one of the first Marquesses of Huntly (inhabitants of Aboyne Castle) on a traditional English village with a green at the centre. The green includes facilities for rugby and football and a play park as well as Aboyne Canoe Clubs storage facility 'The Canoe Cathedral'.

The British Royal Family are residents in nearby Balmoral Castle during the Summer.

Outdoor pursuits include golf, walking, cycling, mountain biking trails, kayaking, canoeing and gliding from the airfield just outside the village. Aboyne has become popular with gliding enthusiasts from Britain and Europe due to its suitable air currents (due to the surrounding terrain). The airfield has two parallel tarmac runways running east–west, a webcam[19] and small weather-monitoring centre[20] on its premises. Aboyne also contains a mountain biking facility at Aboyne Bike Park located in the Bellwood.

The old Aboyne Curling Club had its own private railway station, Aboyne Curling Pond railway station, at the Loch of Aboyne.

The close-by pass of Ballater is a rock-climbing area. The village of Dinnet is a few miles west and is the first being located inside the Cairngorms National Park. Walkers and cyclists can ascend Mount Keen by cycling as far as they can from Glen Tanar forest before walking to the summit.

There are two schools, Aboyne Academy and a primary school. The academy has around 650 pupils, about a third from Aboyne itself, with the remaining two thirds from surrounding villages. The school has access to a full-size swimming pool and gym run by the adjacent Deeside Community Centre.

References

- "Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba (AÀA) – Gaelic Place-names of Scotland". www.gaelicplacenames.org. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- The Online Scots Dictionary.

- "Scotslanguage.com - Names in Scots - Places in Scotland". scotslanguage.com. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "Mid-2016 Population Estimates for Settlements and Localities in Scotland". National Records of Scotland. 12 March 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Aboyne location map Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Field, John (1980). Place-names of Great Britain and Ireland. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. p. 22. ISBN 0389201545. OCLC 6964610.

- "Aboyne-Dinnet Church History". Church of Scotland. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- C. Michael Hogan, Elsick Mounth, Megalithic Portal, ed A. Burnham, 2007

- J.Baynes, The Jacobite Rising of 1715 (1970), pp. 35-36

- "Formaston". The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Pictish/Scottish Names". Peiraeus Public Library. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Mackay, Aeneas James George (1894). "Nechtan". Dictionary of National Biography. 40: 153. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- "Formaston Stone, Aboyne". POWiS. Scottish Church Heritage Research. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Temple, William (1894). The Thanage of Fermartyn. Aberdeen: Wylie. pp. 244–45. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Aitken, Robert (July 1898). "The Knights Templar in Scotland" (PDF). The Scottish Review: 12–13. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- "Aboyne-Dinnet".

- Office, Met. "UK climate". www.metoffice.gov.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "Aboyne (Aberdeenshire) UK climate averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Aboyne Airfield Webcam Archived 21 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Aboyne meteorological data Archived 24 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine