Abu Taghlib

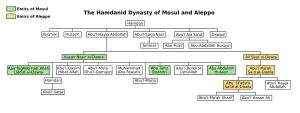

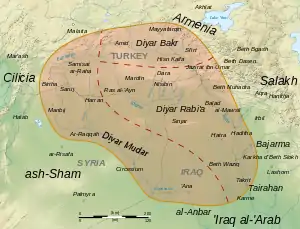

Fadl Allah Abu Taghlib al-Ghadanfar ʿUddat al-Dawla (Arabic: فضل الله أبو تغلب الغضنفر عدة الدولة, romanized: Faḍl Allāh ʿAbu Taghlib al-Ghaḍanfar ʿUddat al-Dawla), usually known simply by his kunya as Abu Taghlib, was the third Hamdanid ruler of the Emirate of Mosul, encompassing most of the Jazira.

| Abu Taghlib أبو تغلب | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emir of Mosul | |||||

| Reign | 967–978 | ||||

| Predecessor | Nasir al-Dawla | ||||

| Died | 29 August 979 Ramla | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Hamdanid | ||||

| Father | Nasir al-Dawla | ||||

His reign was troubled, being marked by conflicts with some of his brothers, antagonism with the various branches of the Buyids for influence in Baghdad, and attacks by the Byzantine Empire under John I Tzimiskes. His relations with the Buyid emir of Iraq, 'Izz al-Dawla Bakhtiyar, were initially hostile, but the two later concluded an alliance. In 978, the Jazira was occupied by the Buyids of Shiraz under 'Adud al-Dawla, and he fled to the Fatimid-controlled parts of Syria, where he tried to secure the governorship of Damascus, and became involved in local rivalries which resulted in his defeat in battle and execution on 29 August 979.

Life

Origin and background

Abu Taghlib was the eldest son of al-Hasan, better known by his laqab of Nasir al-Dawla, who had established the Hamdanids as masters of a practically independent emirate encompassing the Jazira and centred on Mosul. Nasir al-Dawla engaged in repeated attempts to gain control over the Abbasid caliphs at Baghdad, but in the end was forced to concede defeat to the more powerful Buyids, recognize their suzerainty and pay them tribute.[1][2] At the same time, Nasir al-Dawla's younger brother Ali, better known as Sayf al-Dawla, managed to establish his control over northern Syria from his two capitals Aleppo and Mayyafariqin, and through his clashes with the Byzantine Empire quickly overshadowed his brother. However, the last decade of Sayf al-Dawla's rule, until his death in February 967, was marked by heavy military defeats at the hands of the Byzantines, who occupied much of his domains, and internal turmoil.[3][4]

It was in this context that Abu Taghlib is first mentioned in 964, when his father had once again been embroiled in a conflict with the Buyids. The army of the Buyid Mu'izz al-Dawla occupied Mosul and Nasir al-Dawla was once again forced to flee to the hill country of the northern Jazira. Abu Taghlib led the resistance against the Buyids, who, unable to maintain themselves there, evacuated Mosul and reached a new agreement with the Hamdanids. Consequently, Nasir al-Dawla was now increasingly eclipsed by his sons, and was deposed outright and exiled in 967, dying in captivity shortly after.[1][5]

Reign

Abu Taghlib, surnamed al-Ghadanfar ("The Lion"), succeeded his father as emir and head of the Jaziran branch of the Hamdanid family, but almost immediately his authority was contested by a younger half-brother, Hamdan. Nasir al-Dawla had entrusted the latter with the governance of Nisibis, Maridin and Rahba shortly before his deposition, and may have intended to name him as his heir over Abu Taghlib. Hamdan was indeed the only son of Nasir al-Dawla to protest his father's deposition, and refused to recognize Abu Taghlib. With the aid of the new Buyid emir of Iraq, 'Izz al-Dawla Bakhtiyar, Abu Taghlib prevailed over Hamdan, who fled to Baghdad.[7][8][9] In addition, Abu Taghlib used the conditions of near-anarchy prevailing in Syria at the time and after Sayf al-Dawla's death to expand his territory at the expense of his cousin, Sa'd al-Dawla. Upon Sayf al-Dawla's death, Abu Taghlib seized Raqqa and Rafiqa, and by 971 he had extended his control over all of Diyar Bakr and Diyar Mudar, once part of Sayf al-Dawla's domain, uniting the entire Jazira under his rule. Sa'd al-Dawla, deprived of his own capital and lacking any power to offer any resistance, tacitly accepted these losses as well as his cousin's suzerainty.[10] As ruler of the Jazira, Abu Taghlib was one of the richest rulers of the region; Ibn Hawkal's descriptions attest to the wealth derived from the many Hamdanid estates, and Ibn Miskawayh, who was tasked with inventorying the family's mountain strongholds after the Buyid dissolution of the Hamdanid emirate in 979, writes of the immense cash reserves stored there.[11]

Relations with the Buyids were initially good, as Abu Taghlib, unlike his father, had no direct claim on Baghdad, and Bakhtiyar himself was too preoccupied with affairs in Iraq and elsewhere to focus his attention on the Jazira. However, the Buyid prince offered refuge to Hamdan and other disgruntled members of the Hamdanid clan (including another of Abu Taghlib's brothers, Abu Tahir Ibrahim) and intervened in the Hamdanid family quarrels.[12][13] Thus in 970 Hamdan was restored in Rahba thanks to Buyid pressure, only to be chased away again in 971. The exiled prince now urged Bakhtiyar to make war on Abu Taghlib: in 973 the Buyids once again occupied Mosul, while Abu Taghlib with his army outflanked them and threatened Baghdad. The conflict ended in a negotiated settlement in 974 that included in its provisions the award of the laqab of ʿUddat al-Dawla ("Instrument of the Dynasty") to Abu Taghlib by the caliph and the restoration of Hamdan to his domains.[9][12][13] During the same period, Abu Taghlib also faced the attacks of the Byzantines, who under Emperor John I Tzimiskes penetrated deep into the Jazira, forcing the Hamdanids to pay tribute. The devastating raids of 972 were partly avenged through the defeat and capture of the Domestic of the Schools Melias at Amid in 973, but in 974 Tzimiskes himself raided the Jazira in retaliation.[12][14][15]

In 973–975, Abu Taghlib supported Bakhtiyar in his own struggles to safeguard his power. Thus he once again marched on Baghdad during the rebellion of the Turkish military commander, Sabuktigin, although it was the intervention of the Buyid emir of Shiraz, 'Adud al-Dawla, that decided the conflict for Bakhtiyar. As a result of his assistance, in 975 Abu Taghlib secured a revision of the earlier treaty which freed him from the payment of tribute.[9][12][16] In 976, following the death of Tzimiskes, Abu Taghlib agreed to support the bid for the Byzantine throne of the rebel general Bardas Skleros, with whom he concluded a treaty whereby the Hamdanid ruler supplied Skleros with light cavalry in exchange for an unspecified marriage agreement.[12][17]

In 977, as Bakhtiyar found himself driven from Baghdad by the ambitious 'Adud al-Dawla, he turned again to the Hamdanids for aid. Abu Taghlib agreed to support him in exchange for the handing over of Hamdan, who was promptly executed. Although this secured Abu Taghlib's position in his family, it also brought him to the attention of 'Adud al-Dawla. In May 978, Bakhtiyar and Abu Taghlib were defeated in a battle near Samarra by 'Adud al-Dawla. Bakhtiyar himself was captured and executed at the orders of 'Adud al-Dawla, who then advanced on Mosul.[12][18] Unlike earlier Buyid expeditions against the Hamdanids, that had failed chiefly because they were unable to sustain themselves in the Jazira, this was far better organized, as 'Adud al-Dawla brought along experienced administrators familiar with the area.[13] The Buyids took Mosul and forced Abu Taghlib to flee to Mayyafariqin and then to the mountains of Armenia; while the Buyids laid siege to Mayyafariqin, he even visited Skleros in Byzantine territory in Anzitene, trying to secure his assistance, but in vain, for Skleros too was hard-pressed by the loyalist general Bardas Phokas. After the fall of Mayyafariqin in 978, Abu Taghlib fled to Rahba, from where he tried in vain to negotiate with 'Adud al-Dawla.[12][13][19]

Exile and death

With the Buyid troops completing their conquest of the Jazira, and unable to seek aid from his cousin Sa'd al-Dawla, who had already acknowledged 'Adud al-Dawla's suzerainty and was under orders to arrest him, Abu Taghlib with his remaining followers crossed the Syrian Desert to the Fatimid-controlled south of Syria.[12][13] There he became embroiled in the complex power struggles between the Fatimid government and local elites. He endeavoured to gain recognition by the Fatimids as governor of Damascus, but the rebel general al-Qassam, who held the city, repulsed him. Under attack by the Damascenes, and with members of his family starting to desert him, Abu Taghlib moved further south to the region of Lake Tiberias. Abu Taghlib's ambitions and his contacts with the Fatimids now came to threaten the position of Mufarrij ibn Daghfal ibn al-Jarrah, a Tayy chief and ruler of Ramla. Hoping to sow dissension among the Arab tribes of the area and strengthen Fatimid authority, the Fatimid general Fadl now promised Ramla to Abu Taghlib, who openly allied himself with Mufarrij's rivals, the Banu Uqayl, and attacked Ramla in August 979. Fadl's troops, however, came to the aid of Mufarrij, and in the ensuing battle on 29 August Abu Taghlib was taken captive and executed.[12][20]

The Jazira remained under Buyid control until 989, when Abu Taghlib's brothers Abu Abdallah Husayn and Abu Tahir Ibrahim, who had submitted to the Buyids, were installed as governors to oppose the power of the Kurdish chieftain Bādh ibn Dustak, who had taken control of Mosul. In this fight, the two brothers relied upon the Uqaylis; after the defeat of Bādh, the Banu Uqayl turned on the Hamdanids and deposed and killed Abu Tahir Ibrahim, establishing the Uqaylid Dynasty as the rulers of the Jazira.[21][22]

References

- Canard (1971), p. 127

- Kennedy (2004), pp. 268–271

- Canard (1971), p. 129

- Kennedy (2004), pp. 273–280

- Kennedy (2004), p. 271

- Canard (1965)

- Canard (1971), pp. 127–128

- Kennedy (2004), pp. 271–272

- Kraemer (1992), p. 89

- Canard (1971), pp. 127–128, 129

- Holmes (2005), pp. 262–263 esp. note 43

- Canard (1971), p. 128

- Kennedy (2004), p. 272

- Holmes (2005), pp. 308, 325–326

- Kraemer (1992), pp. 89–90

- Kennedy (2004), pp. 223–224

- Holmes (2005), p. 262

- Kennedy (2004), pp. 272, 230

- Holmes (2005), pp. 265–266

- Gil (1997), pp. 354–356

- Canard (1971), pp. 128–129

- Kennedy (2004), pp. 272–273

Sources

- Canard, Marius (1965). "Abū Tag̲h̲lib". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. OCLC 495469475.

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ḥamdānids". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume III: H–Iram. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 126–131. OCLC 495469525.

- Gil, Moshe (1997) [1983]. A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Translated by Ethel Broido. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59984-9.

- Holmes, Catherine (2005). Basil II and the Governance of Empire (976–1025). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927968-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Kraemer, Joel L. (1992). Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam: The Cultural Revival During the Buyid Age (2nd Revised ed.). Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 90-04-09736-8.

| Preceded by Nasir al-Dawla |

Emir of Mosul 967–978 |

Buyid occupation |