Achaemenid destruction of Athens

The Achaemenid destruction of Athens was accomplished by the Achaemenid Army of Xerxes I during the Second Persian invasion of Greece, and occurred in two phases over a period of two years, in 480-479 BCE.

| Achaemenid destruction of Athens | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||

Part of the archaeological remains called Perserschutt, or "Persian rubble": remnants of the destruction of Athens by the armies of Xerxes. Photographed in 1866, just after excavation. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Athens | Achaemenid Empire | ||||||

Location of Athens | |||||||

First phase: Xerxes I (480 BCE)

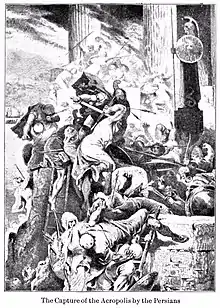

In 480 BCE, after the victory of Xerxes I at the Battle of Thermopylae, all of Boeotia fell to the Achaemenid Army. The two cities that had resisted Xerxes, Thespiae and Plataea, were captured and razed. Attica was also left open to invasion, and the remaining population of Athens was thus evacuated, with the aid of the Allied fleet, to Salamis.[1] The Peloponnesian Allies began to prepare a defensive line across the Isthmus of Corinth, building a wall, and demolishing the road from Megara, thereby abandoning Athens to the Persians.[2]

Athens fell a first time in September 480 BCE.[3] The small number of Athenians who had barricaded themselves on the Acropolis were eventually defeated, and Xerxes then ordered Athens to be torched.[4] The Acropolis was razed, and the Old Temple of Athena and the Older Parthenon destroyed:[5]

Those Persians who had come up first betook themselves to the gates, which they opened, and slew the suppliants; and when they had laid all the Athenians low, they plundered the temple and burnt the whole of the acropolis.

— Herodotus VIII.53[6]

- "Perserschutt", or "Persian rubble"

Numerous remains of statues vandalized by the Achaemenids have been found, known collectively as the "Perserschutt", or "Persian rubble":

Acropolis excavation pit where remains of Archaic statues were found, northwest of the Erechtheum.

Acropolis excavation pit where remains of Archaic statues were found, northwest of the Erechtheum. The Kritios Boy was recovered, decapitated, in the Perserschutt.

The Kritios Boy was recovered, decapitated, in the Perserschutt. The Antenor Kore, recovered from the Perserschutt.

The Antenor Kore, recovered from the Perserschutt. Part of the damaged Hekatompedon pediment.

Part of the damaged Hekatompedon pediment. The damaged Moscophoros.

The damaged Moscophoros. The damaged Peplos Kore.

The damaged Peplos Kore. The damaged Rampin Rider.

The damaged Rampin Rider. The Capture of the Acropolis by the Persians

The Capture of the Acropolis by the Persians

.jpg.webp)

The statue was the "Nike (Victory) of Callimachus" which was erected next to the Older Parthenon in honor of Callimachus and the victory at the Battle of Marathon, was severely damaged by the Achaemenids. The statue depicts Nike (Victory), in the form of a woman with wings, on top of an inscribed column. Its height is 4.68 meters and was made of Parian marble. The head of the statue and parts of the torso and hands were never recovered.

Xerxes also took away some of the statuary, such as the bronze statue of Harmodius and Haristogiton, "the Tyrant-slayers", which was recovered by Alexander the Great in the Achaemenid capital of Susa two centuries later.[7]

In September though, Xerxes I lost a large part of his fleet to the Greeks in the Battle of Salamis. With the Persians' naval superiority removed, Xerxes feared that the Greeks might sail to the Hellespont and destroy the pontoon bridges.[8] According to Herodotus, Mardonius volunteered to remain in Greece and complete the conquest with a hand-picked group of troops, while advising Xerxes to retreat to Asia with the bulk of the army.[9] All of the Persian forces abandoned Attica, with Mardonius over-wintering in Boeotia and Thessaly.[10]

Some Athenians were thus able to return to their burnt-out city for the winter.[10] They would have to evacuate again in front of a second advance by Mardonius in June 479 BCE.[3]

Second phase: Mardonius (479 BCE)

Mardonius remained with the rest of the Achaemenid troops in northern Greece. He selected some of the best troops to remain with him in Greece, especially Immortals, the Medes, the Sacae, the Bactrians and the Indians. Herodotus described the composition of the principal troops of Mardonius:[13][12]

Mardonius there chose out first all the Persians called Immortals, save only Hydarnes their general, who said that he would not quit the king's person; and next, the Persian cuirassiers, and the thousand horse, and the Medes and Sacae and Bactrians and Indians, alike their footmen and the rest of the horsemen. He chose these nations entire; of the rest of his allies he picked out a few from each people, the goodliest men and those that he knew to have done some good service... Thereby the whole number, with the horsemen, grew to three hundred thousand men.

Mardonius remained in Thessaly, knowing an attack on the isthmus was pointless, while the Allies refused to send an army outside the Peloponessus.[16]

Mardonius moved to break the stalemate, by offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion to the Athenians (with the aim of thereby removing their fleet from the Allied forces), using Alexander I of Macedon as an intermediary.[17] The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was on hand to hear the offer, but rejected it.[17] Athens was thus evacuated again, and the Persians marched south and re-took possession of it.[17]

Mardonius brought even more thorough destruction to the city, and some authors considered that the city was truly razed to the ground during this second phase.[3] According to Herodotus, after the negotiations broke off:

(Mardonius) burnt Athens, and utterly overthrew and demolished whatever wall or house or temple was left standing

Reconstruction

The Achaemenids were decisively beaten at the ensuing Battle of Plataea, and the Greeks were able to recover Athens. They had to rebuild everything, including a new Parthenon on the Acropolis. These efforts at reconstruction were led by Themistocles in the autumn of 479 BC, who reused remains of the Older Parthenon and Old Temple of Athena to reinforce the walls of the Acropolis, which are still visible today in the North Wall of the Acropolis.[19][20] His priority was probably to repair the walls and build up the defenses of the city, before even endeavouring to rebuild temples.[21] Themistocles in particular is considered as the builder of the northern wall of the Acropolis incorporating the debris of the destroyed temples, while Cimon is associated with the later building of the southern wall.[22]

The Themistoclean Wall, named after Themistocles, was built right after the war with Persia, in the hope of defending against further invasion. A lot of this building efforts was accomplished using spolia, remains of the destructions from the preceding conflict.

The Parthenon was only rebuilt much later, after more than 30 years had elapsed, by Pericles, possibly because of an original vow that the Temples destroyed by the Achaemenids should not be rebuilt.

Architectural remains of the Old Athena Temple built into the north wall of the Acropolis by Themistocles.

Architectural remains of the Old Athena Temple built into the north wall of the Acropolis by Themistocles. Column drums of the Older Parthenon, reused in the North wall of the Acropolis, by Themistocles.

Column drums of the Older Parthenon, reused in the North wall of the Acropolis, by Themistocles. The Older Parthenon (in black) was destroyed by the Achaemenids, and then rebuilt by Pericles in 438 BCE (in grey).

The Older Parthenon (in black) was destroyed by the Achaemenids, and then rebuilt by Pericles in 438 BCE (in grey). Ruins of the Themistoclean Wall.

Ruins of the Themistoclean Wall.

Retaliatory burning of the Palace of Persepolis

In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great burned down the palace of Persepolis, the principal residence of the defeated Achaemenid dynasty, after a drinking party and at the instigation of Thais. According to Plutarch and Diodorus, this was intended as a retribution for Xerxes' burning of the old Temple of Athena on the Acropolis in Athens (the site of the extant Parthenon) in 480 BC during the Persian Wars.

When the king [Alexander] had caught fire at their words, all leaped up from their couches and passed the word along to form a victory procession in honour of Dionysus. Promptly many torches were gathered. Female musicians were present at the banquet, so the king led them all out for the comus to the sound of voices and flutes and pipes, Thaïs the courtesan leading the whole performance. She was the first, after the king, to hurl her blazing torch into the palace. As the others all did the same, immediately the entire palace area was consumed, so great was the conflagration. It was remarkable that the impious act of Xerxes, king of the Persians, against the acropolis at Athens should have been repaid in kind after many years by one woman, a citizen of the land which had suffered it, and in sport.

— Diodorus of Sicily (XVII.72)

References

- Herodotus VIII, 41

- Holland, p. 300

- Lynch, Kathleen M. (2011). The Symposium in Context: Pottery from a Late Archaic House Near the Athenian Agora. ASCSA. pp. 20–21, and Note 37. ISBN 9780876615461.

- Holland, pp. 305–306

- Barringer, Judith M.; Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (2010). Periklean Athens and Its Legacy: Problems and Perspectives. University of Texas Press. p. 295. ISBN 9780292782907.

- LacusCurtius Herodotus Book VIII: Chapter 53.

- D'Ooge, Martin Luther (1909). The acropolis of Athens. New York : Macmillan. p. 64.

- Herodotus VIII, 97

- Herodotus VIII, 100

- Holland, pp. 327–329

- LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book VIII: Chapters 97‑144. p. Herodotus VIII, 113.

- Shepherd, William (2012). Plataea 479 BCE: The most glorious victory ever seen. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 9781849085557.

- Tola, Fernando (1986). "India and Greece before Alexander". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Vol. 67, No. 1/4. 67 (1/4): 165. JSTOR 41693244.CS1 maint: location (link)

- LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book IX: Chapters 1‑89. pp. IX–31/32.

- The Histories. Penguin UK. 2013. p. 484. ISBN 9780141393773.

- Holland, pp. 333–335

- Holland, pp. 336–338

- LacusCurtius Herodotus Book IX: Chapter 13.

- Shepherd, William (2012). Plataea 479 BC: The most glorious victory ever seen. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 88. ISBN 9781849085557.

- D'Ooge, Martin Luther (1909). The acropolis of Athens. New York : Macmillan. pp. 60–80.

- D'Ooge, Martin Luther (1909). The acropolis of Athens. New York : Macmillan. pp. 64–65.

- D'Ooge, Martin Luther (1909). The acropolis of Athens. New York : Macmillan. p. 66.

Sources

- Holland, Tom (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. Abacus, ISBN 0-385-51311-9.

External links

- Shear, Leslie (1993). The Persian destruction of Athens (PDF).