Ahmad al-Alawi

Ahmad al-Alawi (1869–14 July 1934), (in full, Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Muṣṭafā ibn ʿAlīwa, known as al-ʿAlāwī al-Mustaghānimī Arabic: أبو العباس أحمد بن مصطفى بن عليوة المعروف بالعلاوي المستغانمي), was an Algerian Sufi Sheikh who founded his own Sufi order, called the Alawiyya.[1]

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

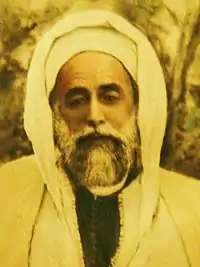

Saint Ahmad al-Alawi | |

|---|---|

An old photograph of Saint Ahmad al-Alawi (c. 1920) | |

| Mystic, Founder | |

| Born | 1869 Mostaganem, Algeria |

| Died | 1934 Mostaganem, Algeria |

| Venerated in | Islam |

| Major shrine | Tomb of Sheikh Ahmad al-Alawi, Mostaganem, Algeria |

| Influences | Ali, Muhammad al-Buzidi, |

Tradition or genre | Darqawa |

| Major works | Munajat of Ahmad al-'Alawi |

Biography

Sheikh Ahmad al-Alawi was born in Mostaganem, Algeria, in 1869. He was educated at home by his father. From the time of his father's death in 1886 until 1894, he worked in Mostaganem.

In 1894, he traveled to Morocco, and followed for fifteen years the Darqawi shaykh Muhammad al-Buzidi. After al-Buzidi's death in 1909, Sheikh Al-Alawi returned to Mostaganem, where he first spread the Darqawiyya, and then (in 1914) established his own order, called the Alawiyya in honor of Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet, who appeared to him in a vision and gave him that name for his new order.

Teachings

Al-Alawi was a Sufi shaykh in the classic Darqawi Shadhili tradition, though his order differed somewhat from the norm in its use of the systematic practice of khalwa and in laying especial emphasis on the invocation of the Supreme Name [of God]..

In addition to being a classic Sufi shaykh, al-Alawi addressed the problems of modern Algerians using modern methods. He wrote poetry and books on established Sufi topics, and founded and directed two weekly newspapers, the short-lived Lisan al-Din (Language of Faith) in 1912, and the longer-lived Al-balagh al-jazairi (Algerian Messenger) in 1926.

Al-Alawi attempted to reconcile Islam and modernity. On the one hand, he criticized Westernization, both at a symbolic level (by discouraging the adoption of Western costumes that lead to ego attachment) and at a practical level (by attacking the growing consumption of alcohol among Algerian Muslims). On the other hand, he encouraged his followers to send their children to school to learn French, and even favored the translation of the Koran into French and Berber for the sake of making it more accessible, a position that was at that time most controversial.

Al-Alawi was critical of both fundamentalist extremism in Islam as well as secularist modernism, typified in Turkey by Kemal Atatürk. For him, the answers to the challenges of modernity were the doctrines and practices of traditional and spiritual Islam and the rites of religion had no other purpose than to cause the "Remembrance of God".[2]

Although al-Alawi showed unusual respect for Christians, and was in some ways an early practitioner of inter-religious dialogue, the centerpiece of his message to Christians was that if only they would abandon the doctrines of the trinity and of incarnation "nothing would then separate us."

The great size of his following may be explained by the combination of classic Sufism with engagement in contemporary issues, combined with his charisma, to which many sources, both Algerian and French, speak. Al-Alawi's French physician, Marcel Carret, wrote of his first meeting with Sheikh al-Alawi "What immediately struck me was his resemblance to the face which is generally used to represent Christ."[3]

The Alawiyya

The Alawiyya spread throughout Algeria, as well as in other parts of North Africa, as a result of Sheikh al-Alawi's travels, preaching and writing, and through the activities of his muqaddams (representatives). By the time of al-Alawi's death in 1934, he had become one of the best known and most celebrated shaykhs of the century and was visited by many.

The Alawiyya was one of the first Sufi orders to establish a presence in Europe, notably among Algerians in France and Yemenis in Wales. Sheikh Al-Alawi himself travelled to France in 1926, and led the first communal prayer to inaugurate the newly built Paris Mosque in the presence of the French president.[1] Sheikh Al-Alawi understood French well, though he was reluctant to speak it.

The Alawiyya branch also spread as far as Damascus, Syria where an authorization was given to Muhammad al-Hashimi who spread the Alawi branch all throughout the lands of the Levant. During the year of 1930, Sheikh Al-Alawi met with Sheikh Sidi Abu Madyan of the Qadiri Boutchichi Tariqah in Mostaganem. They currently have the shortest chain back to Sheikh Al-Alawi. The current Sheikh of the Boutchichi's is Sheikh Sidi Hamza al Qadiri al Boutchichi.

In the modern era, the Alawi-Ahmadi tariqah is one of two prominent Sufi tariqat in Sinai in Egypt. It is prevalent around Jurah and its surrounding areas, such as the areas of Shabbanah, Dhahir, Malafiyyah and Sheikh Zuweid.

Books

- Two Who Attained : Twentieth-Century Sufi Saints: Shaykh Ahmad al-'Alawi & Fatima al-Yashrutiyya, Selections translated from Shaykh Ahmad al-'Alawi's The Divine Graces and a Treatise on the Invocation, ISBN 1-887752-69-2 by Leslie Cadavid (translator) and Seyyed Hossein Nasr (introduction), ed. Fons Vitae (2006)

- On the Unique Name and on 'The Treasury of Truths' of Shaykh Muhammad Ibn al-Habib, ISBN 978-979-96688-0-6, IB Madinah Press (January 31, 2001)

- Lings, Martin, A Sufi saint of the twentieth century: Shaikh Ahmad al-Alawi, his spiritual heritage and legacy, includes a short anthology of al-'Alawi's poetry as the final chapter (12). ISBN 0-946621-50-0

- Munajat of Shaykh Ahmad al-'Alawi: Translated by Abdul-Majid Bhurgri. eBook edition, containing the original Arabic text and the English rendering, can be viewed at http://www.bhurgri.com/bhurgri/downloads/munajat.pdf

Further reading

- Cartigny, Johan (1984). Le Cheikh al-Alawi: témoignages et documents (in French). Drancy, France: Editions Les Amis de l'Islam. OCLC 22709995.

- Jossot, Abdul'karim, Les sentiers d'Allah

- Khelifa, Salah, "Alawisme et Madanisme, des origines immédiates aux années 50." Doctoral thesis, Université Jean Moulin Lyon III.

- Ahmad al-Alawî, "Lettre ouverte à celui qui critique le soufisme", Éditions La Caravane, St-Gaudens, 2001, ISBN 2-9516476-0-3

- Cheikh al-Alawî, "Sagesse céleste - Traité de soufisme", Éditions La Caravane, Cugnaux, 2007, ISBN 2-9516476-2-X

- Schuon, Frithjof, Sufism Veil and Quintessence. USA, World Wisdom, 2006.

- Stoddart, William, Outline of Sufism: The Essentials of Islamic Spiritualit, USA, World Wisdom, 2011.

- Soares de Azevedo, Mateus, Men of a Single Book: Fundamentalism in Islam, Christianity, and modern thought. USA, World Wisdom, 2010. ISBN 978-1-935493-18-1

References

- Mark Sedgwick (13 July 2009). Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-19-539601-0.

- See "Men of a Single Book: Fundamentalism in Islam, Christianity, and modern thought", by Mateus Soares de Azevedo: World Wisdom, 2010, p. 32

- Lings, A Sufi Saint, p. 14.

External links

- Website of Association Internationale Soufie Alawiyya (in French)

- Website of Association Internationale Soufie Alawiyya Germany (in German)

- Website of the Alawiyya Order (in English and Arabic)

- Sheikh Nuh Keller's website of the Shadhili (Darqawi, Alawi) Tariqa (in English)

- Les Amis du Cheikh Ahmed al-Alawi (in French)

- Life of al-Alawi (in Arabic)

- "Layla," poem (in English)

- Tariqa Shadiliya Darqawiya Alawiya (in Spanish)

- Tariqa Shadiliya Darqawiya Alawiya Madaniya Ismailya (in Italian)

- Editions La Caravane (in French)

- Shaykh Ahmad Al-'Alawi, by Karimah K. Stauch (in German and English)