Mouride

The Mouride brotherhood (Wolof: yoonu murit, Arabic: الطريقة المريدية aṭ-Ṭarīqat al-Murīdiyyah or simply المريدية, al-Murīdiyyah) is a large tariqa (Sufi order) most prominent in Senegal and The Gambia with headquarters in the city of Touba, Senegal, which is a holy city for the order. Adherents are called Mourides, from the Arabic word murīd (literally "one who desires"), a term used generally in Sufism to designate a disciple of a spiritual guide.The beliefs and practices of the Mourides constitute Mouridism. Mouride disciples call themselves taalibé in Wolof and must undergo a ritual of allegiance called njebbel, as it is considered highly important to have a sheikh "spiritual guide" in order to become a Mouride.[1] The Mouride brotherhood was founded in 1883 in Senegal by Amadou Bamba. The Mouride make up around 40 percent of the total population, and their influence over everyday life can be seen throughout Senegal.

| Part of a series on |

| Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

History

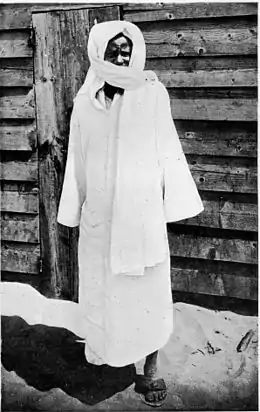

Amadou Bamba

The Mouride brotherhood was founded in 1883 in Senegal by Shaykh Aḥmadu Bàmba Mbàkke (Wolof name), commonly known as Amadou Bamba (1850–1927). In Arabic, he is known as Aḥmad ibn Muhammad ibn Habīb Allāh or by the nickname "Khadīmu r-Rasūl" ("Servant of the Prophet"). In Wolof he is called "Sëriñ Tuubaa" ("Holy Man of Touba). He was born in the village of Mbacké in Baol, the son of a marabout from the Qadiriyya, the oldest of the Muslim brotherhoods in Senegal.

Amadou Bamba was a Muslim mystic and ascetic marabout, a spiritual leader who wrote tracts on meditation, rituals, work, and tafsir. He is perhaps best known for his emphasis on work, and his disciples are known for their industriousness. Although he did not support the French conquest of West Africa, he did not wage outright war on them, as several prominent Tijani marabouts had done. He taught, instead, what he called the jihād al-akbar or "greater struggle," which fought not through weapons but through learning and fear of God.

Bamba's followers call him a mujaddid (a "renewer of Islam"). Bamba's fame spread through his followers, and people joined him to receive the salvation that he promised. Salvation, he said, comes through submission to the marabout and hard work.[2]

There is only one surviving photograph of Amadou Bamba, in which he wears a flowing white kaftan and his face is mostly covered by a scarf. This picture is venerated and reproduced in paintings on walls, buses, taxis, and other private and public spaces all over modern-day Senegal.

French colonial rule

At the time of the foundation of the Mouride brotherhood in 1883, the French were in control of Senegal as well as most of West and North Africa. Although it had shared in the horrors of the pre-colonial slave trade, French West Africa was managed relatively better than other African regions during the Scramble for Africa and ensuing colonial era. Senegal enjoying small measures of self-rule in many areas. However, French rule still discouraged the development of local industry, preferring to force the exchange of raw materials for European finished goods, and a large number of taxation measures were instituted.

At the end of the 19th century, French colonial authorities began to worry about the growing power of the Mouride brotherhood and its potential to resist French colonialism. Bamba, who had converted various kings and their followers, could probably have raised an army against the French had he wanted. Fearful of his power, the French sentenced Bamba to exile in Gabon (1895–1902) and later Mauritania (1903–1907). However, Bamba's exile fueled legends about his miraculous ability to survive torture, deprivation, and attempted executions, and thousands more flocked to his organization. For example, on the ship to Gabon, forbidden from praying, Bamba is said to have broken his leg-irons, leapt overboard into the ocean, and prayed on a prayer rug that miraculously appeared on the surface of the water. In addition, when the French put him in a furnace, he is said to have simply sat down and had tea with Muhammad. In a den of hungry lions, it is said the lions slept beside him.

By 1910, the French realized that Bamba was not waging war against them and was in fact quite cooperative. The Mouride doctrine of hard work served French economic interests, as addressed below. After World War I, the Mouride brotherhood was allowed to grow and in 1926 Bamba began work on the great mosque at Touba where he would be buried one year later.

Structure

Leadership

Amadou Bamba was buried in 1927 at the great mosque in Touba, the holy city of Mouridism and the heart of the Mouride movement. After his death Bamba has been succeeded by his descendants as hereditary leaders of the brotherhood with absolute authority over the followers. The caliph (leader) of the Mouride brotherhood is known as the Grand Marabout and has his seat in Touba. The first five caliphs were all sons of Amadou Bamba, starting with his eldest son:[3]

- Serigne Mouhamadou Moustapha Mbacké, caliph from 1927-1945[4]

- Serigne Mouhamadou Fallilou Mbacké, caliph from 1945-1968[5]

- Serigne Abdou Ahad Mbacké, caliph from 1968-1989[6]

- Serigne Abdou Khadr Mbacké, caliph from 1989-1990[7]

- Serigne Saliou Mbacké (1915-2007), caliph from 1990 until his death on December 28, 2007[8]

- Serigne Mouhamadou Lamine Bara Mbacké, (1925–2010), caliph from 2007-2010. He was the first grandson of Ahmadou Bamba to become caliph.[9]

- Serigne Sidi Moukhtar Mbacké, caliph from July 1, 2010 until his death on January 9, 2018.[10][11]

- Serigne Mountakha Mbacké, incumbent caliph since January 10, 2018.

The Grand Marabout is a direct descendant of Amadou Bamba himself and is considered the spiritual leader of all Mourides. There is a descending hierarchy of lower-rank marabouts, each with a regional following.

Dahiras

Dahiras are urban associations of Mourides-based either on shared allegiances to a particular marabout or common geographical location, for example, a neighborhood or city-specific dahira.[12]

Daaras

Daaras are madrassas or Quranic schools. They were originally founded by the shaykh, his descendants, or disciples to teach the Quran and the khassida (or xassida, poems honoring the Prophet Muhammmad) as well as cultivating the land. Hence they have grown to be associations of Mourides, generally based on shared allegiance to a particular marabout.

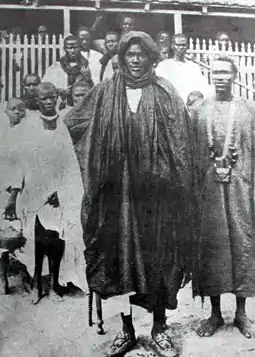

Baye Fall

One famous disciple of Bamba, Ibrahima Fall, was known for his dedication to God and considered work as a form of adoration. Fall was the one to introduce the conduct with which a disciple should interact with his Shaykh, based on the example of the Sahabas and concepts presented in the 49th chapter of the Quran Al-Hujurat.[13] Ibrahima Fall was responsible for guiding many of Bamba's more eccentric followers and new converts to Islam. His followers were the precursor to a subgroup of the Mouride brotherhood today referred to as the Baye Fall (Wolof: Baay Faal), many of whom substitute hard labor and dedication to their marabout for the usual Muslim pieties.

Sheikh Ibrahima Fall was one of the first of Amadou Bamba's disciples and one of the most illustrious.[14] He catalysed the Mouride movement and led all the labour work in the Mouride brotherhood. Fall reshaped the relation between Mouride talibes (disciples) and their guide, Amadou Bamba. Fall instituted the culture of work among Mourides with his concept of Dieuf Dieul, ("you reap what you sow").[15] Ibra Fall helped Amadou Bamba to expand Mouridism, in particular with Fall's establishment of the Baye Fall movement. For this contribution, Serigne Fallou, the second Caliph (leader) after Amadou Bamba, named him "Lamp Fall" (the light of Mouridism).[16] In addition, Ibrahima Fall earned the title باب المريدين Bab al-Murīdīna, "Gate of the Mourides."

The members of the Baye Fall dress in colorful ragged clothes, wear their hair in dreadlocks which are called ndiange ("strong hair"), which they decorate usually with homemade beads, wire or string. They also carry clubs, and act as security guards in the annual Grand Magal pilgrimages to Touba. Women usually are covered in draping coverings including their heads and occasionally are known to wear highly decorative handmade jewelry made from household or natural items. In modern times the hard labor is often replaced by members roaming the streets asking for financial donations for their marabout. Several Baye Fall are talented musicians. A prominent member of the Baye Fall is the Senegalese musician Cheikh Lô.

Beliefs

The Three Pillars of Mouridism

Cheikh Ahmadou Bamba taught the Three Pillars of Mouridism:

In summary, a Mouride aspires to achieve Islam by following the basic recommendations of Shariat. This includes (but is not limited to) performing individual obligations (Fard Ayn) such as prayer, ablution, fasting, pilgrimage and giving charity. A Mouride aspires to achieve Iman by the Six Articles of Faith: Belief in Allâh, his Angels, the Prophets, the revealed Holy Books, the Day of Judgment and the Divine Decree. A Mouride aspires to achieve Ihsan by the path of Tasawwuf (Sufism) through taking initiation (Bayat) with a Sheikh of the Tariqat.

The Mouride Triangle

Additionally to the Three Pillars of Mouridism, the Mourides follow what is called the Mouride Triangle:

- Love: Love for Allâh and his Cheikhs

- Service: Work for Allâh and service for humanity

- Knowledge: With Love and Work over time follows divine light of Allah and knowledge directly to the heart[17]

Renewer of Islam (Mujaddid)

Amadou Bamba is considered a mujaddid (renewer of Islam) by his followers, citing a hadith that implies that God will send renewers of the faith every 100 years. The members of all the Senegalese brotherhoods claim that their founders were such renewers. The Mouride beliefs are based on Quranic and Sufi traditions and influenced by the Qadiri and Tijani brotherhoods, as well as the works by the scholar al-Ghazali. Amadou Bamba is known to have written more than 1000 books in Classical Arabic, all of which are based on the Quran and Hadith. Ahmadou Bamba is known to have said "If it's not in the Qur'an or Hadith, it's not from me".[17] Mourides sometimes call their order the "Way of Imitation of the Prophet". Parents sometimes send their sons to live with the marabout as talibes rather than giving them a conventional education. These boys receive Islamic training and are instilled with the doctrine of hard work.

Many Mourides consider the city of Touba as equally or even more important than Mecca. Pilgrims regularly come to Touba all year round, but the peak of the year is a mass pilgrimage called the Grand Màgal, which celebrates Bamba's return from exile.[18]

Influence in Senegal

Political influence

Senegalese politicians have courted the Mouride brotherhood since independence. Even before independence, French colonial administrators recognized that the Mouride brotherhood was well-respected among the Senegalese and partnered with them to promote political and social order. Traditional Wolof aristocrats had proven problematic as intermediaries for the colonial authorities, and they hoped that Mouride leaders would be more effective and legitimate.[19] When the Senegalese population was allowed to elect a deputy to the French Assembly during the 19th century, the Mouride brotherhood played a key role in shaping who that deputy was. This was the first instance of their role in politics.[20] During the French colonial reign, the marabouts usually gave their support to politicians based upon their support of the brotherhood's leaders and interests.[20] This successful partnership lead to future cooperation between the Senegalese government and the Mouride brotherhood.

After universal suffrage was given in 1956, Senegal saw a rapid increase in the number of voters, almost triple the number just 10 years prior. This swift increase meant more power for the marabout whose outreach spread largely over the rural and peasant communities, which now had the opportunity to vote.[20] A loyal follower of the Mouride is ideologically required to follow his religious leaders instructions, if the follower decided to disregard his instructions, the follower is at risk of losing any material support that would have been given to him.[20] Because of the marabouts far reaching influence in Senegal, politicians made a considerable effort to attain the support from these religious leaders for their personal advancement.[20] In order to attain their support in elections, bribes and material incentives were given to marabouts from political parties and potential candidates.[20] Many believed that no party could hope to attain political power if the marabouts were completely opposed to it, and any party who rose to power had to comply with the Marabout's demands or lose their political support.[20]

While the political elite finds itself regularly in the position of working through the marabouts, their ultimate goal is to function without them. Marabouts for their part seek to maintain and ensure that the state remains dependent on them for influential control over citizens.[21] Besides their influence over many rural and peasant communities, the religious leaders also have other means of maintaining political influence. One such mean is the power the religious leaders have as magicians.[20] In exchange for political favors, these magicians give political leaders a powerful amulet which is thought to bring advancement for oneself or disaster for ones enemies.[20] This power is believed in by many and is sought after by ministers, civil servants, and followers alike. Another aspect of influence that the religious leaders have is the material means to influence local leaders and politicians. The shaikh (religious leaders) can seek to buy the agreement through gifts and help to promote the career or threat to ruin the career of these local politicians and leaders.[20]

Marabout very rarely themselves participate directly in the political process. What is more common is to see them exert their influence over their followers and use this in return to gain a larger presence in the Senegalese politics.[20] Such things as withholding seed from granaries, unless followers purchase party cards, is a way that some marabouts exert their influence in the region to attain votes.[20] Other marabout may actually seek out political office, but most prefer to use their influence as an intermediary of politics in Senegal.[20]

Although recently Mourides have become more involved in the highest level of politics. Abdoulaye Wade who is the immediate former president of Senegal is also a devout Mouride. The day after his election in 2000 Wade travelled to Touba to seek the blessing of the Grand Marabout, Serigne Saliou Mbacké.

Economic influence

Groundnuts are the third largest export from Senegal after fish and phosphates.[22] The amount of groundnut crop which the Mourides produce has been estimated to range from one-third to three-quarters of Senegalese groundnut production, although others have now estimated it to equal around one-half of the national total of groundnuts produced.[20] This partnership between the Brotherhood and the government stems from the French colonial administrators, who had viewed the production of groundnuts by the Mourides as a means of economic advantage through the increasing production of crops for export.[19]

_2006.JPG.webp)

Due to this high proportion of groundnut crop produced by the Mouride, the brotherhood has always seemed to have a large influence in the groundnut market and the economy.[20] Economic involvement is in fact encouraged by the religious leaders to their disciples through the use of ideology that places great value on the production labor which is performed in the service of God.[20] Thus the Mourides devoted themselves to prayer and unpaid agricultural labor in service to their religious leaders. They cultivated the marabout's fields for a decade, and then returned all land profits earned from the groundnut production. After ten years of dedicated work, laborers then received a share of land (large estates were divided up among the laborers). They continued to turn a share of their agricultural output over to their spiritual guide, as groundnut production was the community's only means of sustenance.[19]

The large share of the Mouride's control over the groundnut production has placed them in the center of the nation's economy.[20] The government's economic planners in turn have kept the brotherhood in their minds when establishing policies about groundnut production.[20] Although the government places an importance on the Mouride cultivators, the disciples do not have efficient ways of cultivating groundnuts, and their techniques are often destructive to the land.[20] Rather than looking out for the best use of the land, the Mouride cultivators are more interested in a fast payback. The methods used by the marabout have led to a constant depletion of the forests in Senegal and have taken much of the nutrients out of the soil. Government agencies have made attempts to help the marabout become more efficient in groundnut production, such as providing incentives for the workers to slow down their production.[20]

Because of their emphasis on work, the Mouride brotherhood is economically well-established in parts of Africa, especially in Senegal and the Gambia. In Senegal, the brotherhood controls significant sections of the nation's economy, for example the transportation sector and the peanut plantations. Ordinary followers donate part of their income to the Mouridiya.

Cultural influence

Islam is central to the political sociology of Senegal: the religious elite carry great weight in national politics; political discourse is replete with references and appeals to Islam. There is virtually no opposition to the principle of the secular state, socio-political cleavages based on religion, whether between Muslim and non-Muslim or between Sufi orders, are also virtually non-existent.[21] Within Muslim discourse we find constant reference to such concepts as Islamic government, Islamic economics, or Islamic social order. The essential Islamic core lies in the shared belief in the fundamental unity of the Muslim world.[21] The sense of belonging to a larger community, felt by many Muslims, is reinforced by the common use of Arabic as the language of prayer and religious learning.[21]

Islam is a powerful mobilization instrument and provides the rhetoric for the formulation of ideological movements, and serves as a force for mobilizing people in the pursuit of goals defined by those movements.[21] The role of local Islamic social structures, the nature of leadership and the relations between leaders and followers, the nature and sources of power and authority and the limits and constraints of the economy are all factors, which mediate and direct the impact of Islam on Politics.[21] Senegalese elites have not found appeals to ethnic solidarity a productive means of building a mass following. Common religious affiliation has played a role in defusing the potential for tensions that arise from other social cleavages. There however remains a potential for ethnic and caste divides to enter the Senegalese socio-political organization.[21]

The Senegalese have a mystical aspect to Islam, much like other Sufism brotherhoods. In Senegal, Islamic practice usually requires membership in religious brotherhoods that are dedicated to the marabouts of these groups. Marabouts are believed to be the mediators between Allah and the people. The people seek the help of marabouts for protection from the evil spirits, to improve one's status (in terms of career, love or relationship, finances etc.), to obtain a cure or remedy for sickness, or even to curse an enemy. Marabouts are believed to have the ability to deal with the spirit world and seek the spirits’ help in things impossible for humans. The spirits’ help is sought since they are thought to be a source of much baraka "blessings, divine grace".[18]

The marabouts of the Mouride Brotherhood devote less time to study and teaching than other brotherhoods. They devote most of their time to ordering their disciples’ work and making amulets for their disciples' work and making amulets for their followers. Devout Mourides’ homes and workplaces are covered with pictures and sayings of their marabout, and they wear numerous amulets prepared by them. These acts are believed to bring them a better life and solve their problems as well. Even taxi and bus drivers fill their vehicles with stickers, paintings and photos of the marabouts of their particular brotherhoods.[18]

The marabout-talibe relationship in Senegal is essentially a relationship of personal dependence. It can be a charismatic or a clientelistic relationship. In a charismatic relationship demonstrations of devotion and abnegation towards the marabouts can only explained because their talibes see them as intercessors or even intermediaries with god. This charismatic relationship is reinforced and complemented by a parallel clientelistic relationship between marabout and follower. The results is that marabouts are expected to provide certain material benefits to their follower in addition to the spiritual ones.[21]

This patronage function has been important in the distribution of land, especially during periods of expanding peanut cultivation. Mouride social organization was developed in the context of the expanding peanut economy and its unique formulation was adapted to the economic imperatives of that context. The most distinctive institutional expression of Mouride agro-religious innovation is the daara, an agricultural community of young men in the service of a marabout. These collective farms were largely responsible for the expansion of peanut cultivation.[21] A Mouride peasant may submit to a marabout's organization of agricultural work because it is the best option available to him, independently of the ideology which supports it.[21]

In contrast to a vision of masses blindly manipulated by a religious elite, the ties of talibes to their marabouts are frequently far more contingent and tenuous than assumed. As a result, marabouts confront the problem of recruiting and retaining followers. People at times confront a choice of which marabout to follow, the level of attachment to that marabout, and the domains or situations in which to follow him. While there is a widespread belief in the marabout system in Senegal and a strong commitment to it, it is not necessarily accompanied by an absolute attachment to any one living marabout.[21]

Influence outside Senegal

The brotherhood has a sizable representation in certain large cities in Europe and the United States. Most of these cities with a large Senegalese immigrant population have a Keur Serigne Touba (Residence of the Master of Touba), a seat for the community which accommodates meetings and prayers while also being used as a provisional residence for newcomers. In Paris and New York City, a number of the Mouride followers are small-scale street merchants. They often send money back to the brotherhood leaders in Touba.

In 2004 Senegalese musician Youssou N'Dour released his Grammy Award winning album Egypt, which documents his Mouride beliefs and retells the story of Amadou Bamba and the Mouridiya. His intent was devotional, and the album was received that way in the West, but local some Mourides mistook "Egypt" for pop music using Islamic prayers, and initially expressed displeasure, which frustrated Youssou.

References

Notes

- O'Brien, Donal Brian Cruise (1971). The Mourides of Senegal: the political and economic organization of an Islamic brotherhood. Clarendon Press.

- "Khadim Rassoul Foundation of North America". toubacincinnati.org. Retrieved 2018-07-10.

- Mbacke, Saliou (January 2016). The Mouride Order (PDF). World Faiths Development Dialogue. Georgetown University: Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- "Serigne Muhammadu Moustapha Mbacke (1927-1945)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Muhammadu Fadal Mbacke (1945-1968)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Abdul Ahad Mbacke (1968-1989)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Abdu Qadr Mbacke (1988-1989)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Salihu Mbacke (1915 – 2007)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Muhammadu Lamine Bara Mbacke (2007-2010)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Serigne Sidy Muqtar Mbacke (2010-current)". Murid Islamic Community in America. Retrieved Nov 5, 2019.

- "Décès de Cheikh Mouhamadou Lamine Bara Mbacké," APS, July 1, 2010. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-12-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bava, Sophie (August 2001). "The Mouride Dahira: Between Marseille and Touba". ISIM Newsletter: 7. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- Fall, Ibrahima. Jazbul Murid. Jazbul Murid. N/A, Manuscript.

- Savishinsky, J. N. (1994) The Baye Fall of Senegambia: Muslim Rastas in the Promised Land? Africa: Journal International African Institute, 64, 211-219

- Les origines de Cheikh Ibra Fall (2000, December). Touba', Bimestriel Islamique d'Informations Générales. Retrieved May 25, 2007 from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-07-08. Retrieved 2007-06-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ngom, Fallou (June 2002). "Linguistic Resistance in the Murid Speech Community in Senegal". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 23 (3): 214–226. doi:10.1080/01434630208666466.

- Sufi, Cheikh p: #

- Senegal Society and Culture Report. Petaluma, CA: World Trade Press. 2010.

- Boone, Catherine (2003). Political Topographies of the African State. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 46–67.

- O'Brien, Cruise (1971). The Mourides of Senegal: The Political and Economic Organization of Islamic Brotherhood. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Villalón, Leonardo (1995). Islamic Society and State Power in Senegal. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Adigbli, Koffigan. "Groundnut Production in Freefall". Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

Sources

- Coulon, Christian (1981). Le Marabout et le Prince: Islam et Pouvoir au Senegal. A. Pedone, Paris. ISBN 2-233-00100-1.

- Coulon, Christian (April 1999). "The Grand Magal in Touba: A Religious Festival of the Mouride Brotherhood of Senegal". African Affairs. 98 (391): 195–210.

- Sufi, Cheikh Ahmadou (2017). The Path of the Murid Sadiq. ISBN 9781541399518.

- Islamic Society and State Power in Senegal: Disciples and Citizens in Fatick. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK. 1995. ISBN 0-521-46007-7.

- Ukrainian Immigrants in Touba. travelblog.org, November 10, 2007, retrieved 2007-11-13.

- Thiam, Cheikh (2005) Mouridism: a local re-invention of the modern Senegalese socio-economic order in West Africa Review, Issue 8 (2005), ISSN 1525-4488.

- Mecca too far? Senegalese Muslims head for Touba By Daniel Flynn, Reuters. Mon Mar 12, 2007.

- Industrious Senegal Muslims Run a 'Vatican' By Norimitsu Onishi, New York Times Published: May 2, 2002, retrieved 2007-11-13.

- A song and a prayer. by Mark Hudson Interview and portrait of Youssou N'Dour, The Observer. Sunday May 23, 2004.

On Touba: "And to the orthodox fundamentalist it's utter heresy. Bringing bin Laden here would be like taking Ian Paisley to the Mexican Day of the Dead." - Profiting from One's Prayers, by Joel Millman No such article exists on this webpage as of October 10, 2012., Forbes magazine, 1996.

- Inside the Holy City of Touba, by Kabiru A. Yusuf. No such article exists on this webpage as of October 10, 2012 The Weekly Trust (Kaduna, Nigeria), May 8, 2000.

- Boone, Catherine. 2003. Political Topographies of the African State. New York: Cambridge University Press. 46-67

- World Trade Press. (2010) Senegal Society and Culture Complete Report. World Trade Press, Petaluma, CA, USA

- This article incorporates information from the French and German Wikipedia articles on this subject.

External links

- The Online Murid Library (DaarayKamil.com) This is a bilingual English/French language webpage - accessed October 10, 2012.

- Khassida en PDF (texts of traditional Mouride poems)

- Khassida MP3 (audio of traditional Mouride poems)

- e-Khassida (traditional Mouride poems)