Airlines PNG Flight 1600

On 13 October 2011, Airlines PNG Flight 1600, a Dash 8 regional aircraft on a domestic flight from Lae to Madang, Papua New Guinea, crash-landed in a forested area near the mouth of the Gogol River, after losing all engine power. Only four of the 32 people on board survived.[1][2] It was the deadliest plane crash in the history of Papua New Guinea.[3]

The wreckage of Flight 1600 at the crash site, as illustrated in the final report | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 13 October 2011 |

| Summary | Forced landing following dual propeller failure |

| Site | 20 km south of Madang Airport, Papua New Guinea 5°22′19″S 145°41′19″E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | de Havilland Canada DHC-8-102 |

| Operator | Airlines PNG |

| IATA flight No. | CG1600 |

| Registration | P2-MCJ |

| Flight origin | Lae Nadzab Airport, Papua New Guinea |

| Destination | Madang Airport, Papua New Guinea |

| Occupants | 32 |

| Passengers | 29 |

| Crew | 3 |

| Fatalities | 28 |

| Injuries | 4 |

| Survivors | 4 |

The subsequent investigation found that the flight crew had inadvertently retarded the power levers below the lowest position allowable in flight (known as flight idle), causing both propellers to overspeed and leading to a complete loss of engine power. A 'beta lockout' mechanism that would have prevented the overspeed even in case of erroneous power lever setting was available but not installed on the accident aircraft. Installation of such mechanism became subsequently mandatory on all DHC-8 aircraft worldwide.[4]

History of flight

On the afternoon of 13 October 2011, the Airlines PNG Dash 8 was conducting a regular public transport flight from Lae Nadzab Airport, to Madang Airport. On board were two flight crew, a flight attendant, and 29 passengers.

The plane departed from Nadzab at 16:47 local time. The captain, 64-year-old Australian Bill Spencer, had logged 18,200 hours of flying experience, of which 500 on the Dash 8. The first officer was 40-year-old New Zealander Campbell Wagstaff, with 2,725 hours logged, of which 390 on the type.[5][6] Spencer was the handling pilot. The aircraft climbed to 16,000 ft with an estimated arrival time at Madang of 17:17. Once in the cruise, the flight crew diverted right of the flight planned track to avoid thunderstorms and cloud.

The planned route required a steep descent into Madang and, although the aircraft was descending steeply, the propellers were left at their cruise setting of 900 rpm, causing the airspeed to increase. Neither pilot noticed the airspeed increasing towards the maximum operating speed (VMO); as they were "distracted by the weather". When the aircraft reached VMO as it passed through 10,500 ft, with a rate of descent between 3,500 and 4,200 ft per minute, the VMO overspeed warning sounded.[7]

Spencer asked Wagstaff to increase the propeller speed to 1,050 rpm to slow the aircraft down. He raised the nose of the aircraft in response to the warning and this reduced the rate of descent to about 2,000 ft per minute, however, the VMO overspeed warning continued.[7]

Propeller overspeed

Wagstaff recalled Spencer moving the power levers back "quite quickly." Shortly after the power levers had been moved back, both propellers oversped simultaneously, exceeding by over 60% their maximum permitted speed of 1,200 rpm and seriously damaging both engines. The noise in the cockpit became deafening, rendering communication between the pilots extremely difficult, and internal damage to the engines caused smoke to enter the cockpit and cabin through the air conditioning system.[7]

The emergency caught both pilots by surprise. There was confusion and shock on the flight deck. About four seconds after the double propeller overspeed began, the beta warning horn started to sound intermittently, although the pilots stated afterwards they did not hear it.[7]

The left propeller speed reduced to 900 rpm (in the governing range) after about 10 seconds, before overspeeding again. During this second overspeed, the left engine compressor speed increased above 110% of its nominal value, suffering severe damage. Almost simultaneously, the right propeller went into uncommanded feather due to a malfunctioning beta switch in the propeller control unit, while the engine was still running at flight idle. Wagstaff then told Spencer that the right engine had shut down. He then asked to Spencer if the left engine was still working. Spencer replied that it was not working. Both pilots then agreed that they had "nothing".[7]

On the order of Spencer, Wagstaff made a mayday call to Madang Tower and gave the aircraft's co-ordinates. However, instead of checking emergency checklists and procedures, their attention turned to where they were going to make a forced landing.[7]

The aircraft crash-landed near the banks of the Gogol River tail-first at 114 knots, with flaps and landing gear retracted. During the impact sequence, the left wing and tail became detached.

The wreckage came to rest 300 metres from the initial impact point and was engulfed by fire. The front of the aircraft fractured behind the cockpit and came to rest inverted. Of the 32 occupants of the aircraft, only the two pilots, the only flight attendant, and one passenger out of 29 survived.[8]

Aircraft

The aircraft involved was a twin-engine de Havilland Canada DHC-8-102 with Papua New Guinean registration P2-MCJ, first flown in 1988. It was fitted with two turboprop engines Pratt & Whitney Canada PW121 and constant-speed propellers.[9]

Passengers

The plane was carrying 29 passengers, mostly Papua New Guineans, with one reported to be a Malaysian-Chinese national, who was the only surviving passenger. Most of the passengers were parents tried to attend thanksgiving ceremonies ahead of the graduation of their children at Divine Word University in Madang.[10]

Investigation

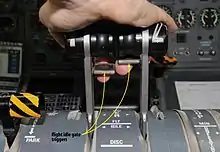

An investigation was carried out by the Accident Investigation Commission of Papua New Guinea (AIC) with assistance from the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. The final report was issued on 15 June 2014. The AIC found that the pilot in command pulled the power levers beyond the flight idle gate and into the ground beta range, while attempting to slow the aircraft down during descent in bad weather. Ground beta (the propeller's reverse pitch range) should only be used for decelerating or reversing on the ground, as in flight it can cause uncontrollable propeller overspeed and damage to the engines.[7][11]

The mechanism that alerts pilots that they are selecting beta range had been the subject of previous investigations and it was found that a manufacturer-approved service centre had a history of releasing defective parts back to operators.

Following a number of previous incidents of inadvertent selection of Ground Beta range on Dash 8 aircraft, that resulted in serious damage to engines, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration mandated that an additional safeguard was required to be fitted to aircraft operated by U.S. airlines. This system, called a Beta Lockout, was developed by the manufacturer and completely prevents inadvertent selection of Ground Beta range while airborne at high speeds, but operators outside the U.S. were not notified or required to fit the modification. The report also found that the crew had to deal with an overspeed of both propellers that caused large amounts of drag making the aircraft extremely difficult to control and that there was significant noise caused by the propeller tips exceeding the speed of sound and also smoke in the cockpit and cabin due to the damage to the engines and bleed air system.

The report criticised the pilots for their failure to control the aircraft's rate of descent and speed both before and after the overspeed and noted that one engine was still capable of providing some accessory services during the forced landing even though it could not provide propulsion. The pilots shut this engine down and therefore lost the ability to use hydraulic and electrical systems that might have improved the survivability of the forced landing.[7]

Aftermath

After the crash, Airlines PNG decided to ground its entire fleet of 12 Dash 8s pending investigation.[12] It also quarantined a fuel depot at Lae Nadzab Airport from which the crashed aircraft was refuelled before departing on the accident flight.[13]

Following release of the initial accident findings, Airlines PNG added the Beta Lockout mechanism as a modification to all their Dash 8s, preventing the inadvertent selection of Ground Beta in flight. Subsequently, Transport Canada in conjunction with the aircraft manufacturer released an airworthiness directive making it a mandatory requirement that all operators worldwide make these modifications.[14]

On 14 October 2015, 4th anniversary of the crash, a candlelight memorial was held at Divine World University in Madang, as most of the victims were parents attending their children's Graduation Day. The memorial service was attended by staff and students from the university.[15]

See also

- Air Caraïbes Flight 1501, a similar crash in Guadeloupe in which the pilots accidentally changed the aircraft's propeller switch into reverse pitch while still in mid-air

- Luxair Flight 9642, a similar crash in Luxembourg involving a Fokker 50 in which the pilots accidentally changed the aircraft's propeller switch into reverse pitch while still in mid-air

- Kish Air Flight 7170, a similar crash in United Arab Emirates involving a Fokker 50 in which the pilots accidentally changed the aircraft's propeller switch into reverse pitch while still in mid-air

- Merpati Nusantara Airlines Flight 6517, a similar crash in Indonesia involving a Xian MA60 in which the pilots accidentally changed the aircraft's propeller switch into reverse pitch while still in mid-air

References

- Fox, Liam (14 October 2011). "More than 20 dead in PNG plane crash". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- "Aussie pilot survives as 28 die in PNG plane crash". Sydney Morning Herald. 14 October 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- "28 die in Papua New Guinea's worst plane crash". Capital F.M. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "Kiwi pilot blamed for deadly PNG crash". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "Aussie pilot survives as 28 die in PNG plane crash". SMH.co.au. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Fox, Liam (15 October 2011). "Black boxes retrieved from PNG plane crash". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Airlines PNG P2-MCJ Bombardier DHC-8-103 Double propeller overspeed 35 km south south east of Madang (PDF) (Report). Papua New Guinea Accident Investigation Commission. 15 June 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2016.

- "Plane crash kills 28 in Papua New Guinea". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. 13 October 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- "28 dead in Papua New Guinea plane crash". Telegraph. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "Collision with terrain – de Havilland Dash 8, P2-MCJ, 20 km S of Madang, PNG, 13 October 2011". Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Australian Government. 14 October 2011. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- "Airlines PNG grounded after crash". Herald Sun. 14 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Witter, Anne (14 October 2011). "Airlines PNG Grounds Fleet of 12 Dash 8 Aircraft, Pilots from Australia and New Zealand Rescued". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- "Airlines PNG modifies its Dash 8 aircraft after fatal plane crash in Madang in 2011". Australia Network News. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- "Candles in memory of 28 plane crash victim". Loop PNG. Retrieved 26 January 2016.