Ajax (programming)

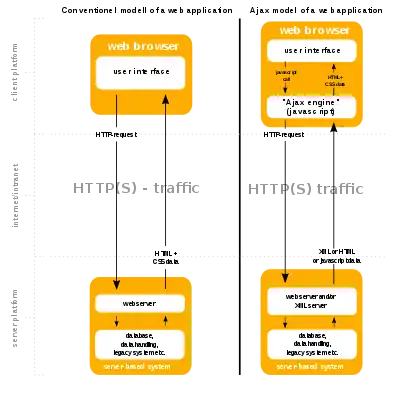

Ajax (also AJAX /ˈeɪdʒæks/; short for "Asynchronous JavaScript and XML")[1][2] is a set of web development techniques using many web technologies on the client-side to create asynchronous web applications. With Ajax, web applications can send and retrieve data from a server asynchronously (in the background) without interfering with the display and behaviour of the existing page. By decoupling the data interchange layer from the presentation layer, Ajax allows web pages and, by extension, web applications, to change content dynamically without the need to reload the entire page.[3] In practice, modern implementations commonly utilize JSON instead of XML.

| First appeared | March 1999 |

|---|---|

| Filename extensions | .js |

| File formats | JavaScript |

| Influenced by | |

| JavaScript and XML | |

Ajax is not a single technology, but rather a group of technologies. HTML and CSS can be used in combination to mark up and style information. The webpage can then be modified by JavaScript to dynamically display—and allow the user to interact with—the new information. The built-in XMLHttpRequest object, or since 2017 the new "fetch()" function within JavaScript, is commonly used to execute Ajax on webpages, allowing websites to load content onto the screen without refreshing the page. Ajax is not a new technology, or a different language, just existing technologies used in new ways.

History

In the early-to-mid 1990s, most Web sites were based on complete HTML pages. Each user action required that a complete new page be loaded from the server. This process was inefficient, as reflected by the user experience: all page content disappeared, then the new page appeared. Each time the browser reloaded a page because of a partial change, all of the content had to be re-sent, even though only some of the information had changed. This placed additional load on the server and made bandwidth a limiting factor on performance.

In 1996, the iframe tag was introduced by Internet Explorer; like the object element, it can load or fetch content asynchronously. In 1998, the Microsoft Outlook Web Access team developed the concept behind the XMLHttpRequest scripting object.[4] It appeared as XMLHTTP in the second version of the MSXML library,[4][5] which shipped with Internet Explorer 5.0 in March 1999.[6]

The functionality of the Windows XMLHTTP ActiveX control in IE 5 was later implemented by Mozilla, Safari, Opera and other browsers as the XMLHttpRequest JavaScript object.[7] Microsoft adopted the native XMLHttpRequest model as of Internet Explorer 7. The ActiveX version is still supported in Internet Explorer, but not in Microsoft Edge. The utility of these background HTTP requests and asynchronous Web technologies remained fairly obscure until it started appearing in large scale online applications such as Outlook Web Access (2000)[8] and Oddpost (2002).

Google made a wide deployment of standards-compliant, cross browser Ajax with Gmail (2004) and Google Maps (2005).[9] In October 2004 Kayak.com's public beta release was among the first large-scale e-commerce uses of what their developers at that time called "the xml http thing".[10] This increased interest in AJAX among web program developers.

The term AJAX was publicly used on 18 February 2005 by Jesse James Garrett in an article titled Ajax: A New Approach to Web Applications, based on techniques used on Google pages.[1]

On 5 April 2006, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) released the first draft specification for the XMLHttpRequest object in an attempt to create an official Web standard.[11] The latest draft of the XMLHttpRequest object was published on 6 October 2016,[12] and the XMLHttpRequest specification is now a living standard.[13]

Technologies

The term Ajax has come to represent a broad group of Web technologies that can be used to implement a Web application that communicates with a server in the background, without interfering with the current state of the page. In the article that coined the term Ajax,[1][3] Jesse James Garrett explained that the following technologies are incorporated:

- HTML (or XHTML) and CSS for presentation

- The Document Object Model (DOM) for dynamic display of and interaction with data

- JSON or XML for the interchange of data, and XSLT for XML manipulation

- The XMLHttpRequest object for asynchronous communication

- JavaScript to bring these technologies together

Since then, however, there have been a number of developments in the technologies used in an Ajax application, and in the definition of the term Ajax itself. XML is no longer required for data interchange and, therefore, XSLT is no longer required for the manipulation of data. JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) is often used as an alternative format for data interchange,[14] although other formats such as preformatted HTML or plain text can also be used.[15] A variety of popular JavaScript libraries, including JQuery, include abstractions to assist in executing Ajax requests.

Drawbacks

- Any user whose browser does not support JavaScript or XMLHttpRequest, or has this functionality disabled, will not be able to properly use pages that depend on Ajax. The only way to let the user carry out functionality is to fall back to non-JavaScript methods. This can be achieved by making sure links and forms can be resolved properly and not relying solely on Ajax.[16]

- Similarly, some Web applications that use Ajax are built in a way that cannot be read by screen-reading technologies, such as JAWS. The WAI-ARIA standards provide a way to provide hints in such a case.[17]

- Screen readers that are able to use Ajax may still not be able to properly read the dynamically generated content.[18]

- The same-origin policy prevents some Ajax techniques from being used across domains,[11] although the W3C has a draft of the XMLHttpRequest object that would enable this functionality.[19] Methods exist to sidestep this security feature by using a special Cross Domain Communications channel embedded as an iframe within a page,[20] or by the use of JSONP.

- Ajax is designed for one-way communications with the server. If two way communications are needed (i.e. for the client to listen for events/changes on the server), then WebSockets may be a better option.[21]

- In pre-HTML5 browsers, pages dynamically created using successive Ajax requests did not automatically register themselves with the browser's history engine, so clicking the browser's "back" button may not have returned the browser to an earlier state of the Ajax-enabled page, but may have instead returned to the last full page visited before it. Such behavior — navigating between pages instead of navigating between page states — may be desirable, but if fine-grained tracking of page state is required, then a pre-HTML5 workaround was to use invisible iframes to trigger changes in the browser's history. A workaround implemented by Ajax techniques is to change the URL fragment identifier (the part of a URL after the "#") when an Ajax-enabled page is accessed and monitor it for changes.[22][23] HTML5 provides an extensive API standard for working with the browser's history engine.[24]

- Dynamic Web page updates also make it difficult to bookmark and return to a particular state of the application. Solutions to this problem exist, many of which again use the URL fragment identifier.[22][23] On the other hand, as AJAX-intensive pages tend to function as applications rather than content, bookmarking interim states rarely makes sense. Nevertheless, the solution provided by HTML5 for the above problem also applies for this.[24]

- Depending on the nature of the Ajax application, dynamic page updates may disrupt user interactions, particularly if the Internet connection is slow or unreliable. For example, editing a search field may trigger a query to the server for search completions, but the user may not know that a search completion popup is forthcoming, and if the Internet connection is slow, the popup list may show up at an inconvenient time, when the user has already proceeded to do something else.

- Excluding Google,[25] most major Web crawlers do not execute JavaScript code,[26] so in order to be indexed by Web search engines, a Web application must provide an alternative means of accessing the content that would normally be retrieved with Ajax. It has been suggested that a headless browser may be used to index content provided by Ajax-enabled websites, although Google is no longer recommending the Ajax crawling proposal they made in 2009.[27]

Examples

JavaScript example

An example of a simple Ajax request using the GET method, written in JavaScript.

get-ajax-data.js:

// This is the client-side script.

// Initialize the HTTP request.

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open('GET', 'send-ajax-data.php');

// Track the state changes of the request.

xhr.onreadystatechange = function () {

var DONE = 4; // readyState 4 means the request is done.

var OK = 200; // status 200 is a successful return.

if (xhr.readyState === DONE) {

if (xhr.status === OK) {

console.log(xhr.responseText); // 'This is the output.'

} else {

console.log('Error: ' + xhr.status); // An error occurred during the request.

}

}

};

// Send the request to send-ajax-data.php

xhr.send(null);

send-ajax-data.php:

<?php

// This is the server-side script.

// Set the content type.

header('Content-Type: text/plain');

// Send the data back.

echo "This is the output.";

?>

Many developers dislike the syntax used in the XMLHttpRequest object, so some of the following workarounds have been created.

jQuery example

The popular JavaScript library jQuery has implemented abstractions which enable developers to use Ajax more conveniently. Although it still uses XMLHttpRequest behind the scenes, the following is a client-side implementation of the same example as above using the 'ajax' method.

$.ajax({

type: 'GET',

url: 'send-ajax-data.php',

dataType: "JSON", // data type expected from server

success: function (data) {

console.log(data);

},

error: function(error) {

console.log('Error: ' + error);

}

});

jQuery also implements a 'get' method which allows the same code to be written more concisely.

$.get('send-ajax-data.php').done(function(data) {

console.log(data);

}).fail(function(data) {

console.log('Error: ' + data);

});

Fetch example

Fetch is a new native JavaScript API.[28] According to Google Developers Documentation, "Fetch makes it easier to make web requests and handle responses than with the older XMLHttpRequest."

fetch('send-ajax-data.php')

.then(data => console.log(data))

.catch (error => console.log('Error:' + error));

ES7 async/await example:

async function doAjax() {

try {

const res = await fetch('send-ajax-data.php');

const data = await res.text();

console.log(data);

} catch (error) {

console.log('Error:' + error);

}

}

doAjax();

As seen above, fetch relies on JavaScript promises.

See also

- ActionScript

- Comet (programming) (also known as Reverse Ajax)

- Google Instant

- HTTP/2

- List of Ajax frameworks

- Node.js

- Remote scripting

- Rich Internet application

- WebSocket

- HTML5

- JavaScript

References

- Jesse James Garrett (18 February 2005). "Ajax: A New Approach to Web Applications". AdaptivePath.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

- "Ajax - Web developer guides". MDN Web Docs. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- Ullman, Chris (March 2007). Beginning Ajax. wrox. ISBN 978-0-470-10675-4. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- "Article on the history of XMLHTTP by an original developer". Alexhopmann.com. 31 January 2007. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- "Specification of the IXMLHTTPRequest interface from the Microsoft Developer Network". Msdn.microsoft.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- Dutta, Sunava (23 January 2006). "Native XMLHTTPRequest object". IEBlog. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- "Dynamic HTML and XML: The XMLHttpRequest Object". Apple Inc. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Hopmann, Alex. "Story of XMLHTTP". Alex Hopmann’s Blog. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "A Brief History of Ajax". Aaron Swartz. 22 December 2005. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- English, Paul (12 April 2006). "Kayak User Interface". Official Kayak.com Technoblog. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- van Kesteren, Anne; Jackson, Dean (5 April 2006). "The XMLHttpRequest Object". W3.org. World Wide Web Consortium. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Kesteren, Anne; Aubourg, Julian; Song, Jungkee; Steen, Hallvord R. M. "XMLHttpRequest Level 1". W3.org. W3C. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "XMLHttpRequest Standard". xhr.spec.whatwg.org. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "JavaScript Object Notation". Apache.org. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- "Speed Up Your Ajax-based Apps with JSON". DevX.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- Quinsey, Peter. "User-proofing Ajax". Archived from the original on 19 February 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- "WAI-ARIA Overview". W3C. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- Edwards, James (5 May 2006). "Ajax and Screenreaders: When Can it Work?". sitepoint.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- "Access Control for Cross-Site Requests". World Wide Web Consortium. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- "Secure Cross-Domain Communication in the Browser". The Architecture Journal (MSDN). Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Pimentel, Victoria; Nickerson, Bradford G. (8 May 2012). "Communicating and Displaying Real-Time Data with WebSocket". IEEE Internet Computing. 16 (4): 45–53. doi:10.1109/MIC.2012.64.

- "Why use Ajax?". InterAKT. 10 November 2005. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- "Deep Linking for AJAX". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- "HTML5 specification". Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Hendriks, Erik (23 May 2014). "Official news on crawling and indexing sites for the Google index". Google. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- Prokoph, Andreas (8 May 2007). "Help Web crawlers efficiently crawl your portal sites and Web sites". IBM. Archived from the original on 19 February 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- "Deprecating our AJAX crawling scheme". Google Webmaster Central Blog. 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- "Fetch API - Web APIs". MDN. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AJAX (programming). |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: AJAX |

- Ajax: A New Approach to Web Applications — Article that coined the Ajax term and Q&A

- Ajax (programming) at Curlie

- Ajax Tutorial with GET, POST, text and XML examples.