Alfred R. Lindesmith

Alfred Ray Lindesmith (August 3, 1905 – February 14, 1991) was an Indiana University professor of sociology. He was among the early scholars providing a rigorous and thoughtful account of the nature of addiction.

Alfred R. Lindesmith | |

|---|---|

| Born | August 3, 1905 Clinton Falls Township, Steele County, Minnesota |

| Died | February 14, 1991 (aged 85) Bloomington, Indiana |

| Alma mater | Carleton College, Columbia University, University of Chicago |

| Known for | Advocacy of a medical approach to drug addiction. |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Sociology, Criminology |

| Institutions | Indiana University |

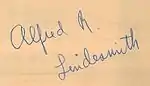

| Signature | |

| |

Lindesmith's interest in drugs began at the University of Chicago, where he was trained in social psychology by Herbert Blumer and Edwin Sutherland, earning his doctorate in 1937. His education there was a mixture of the analytical and theoretical, a balance that would later appear in his drug studies. The work at Chicago involved research with interactionist theory, including the research of Chicago's Herbert Blumer, emphasizing the idea of self-concept in human interaction.

Theory of addiction

Lindesmith's work on drugs began with his questioning of the nature of addiction in a 1938 essay entitled "A sociological theory of drug addiction". This paper appeared in the American Journal of Sociology and involved in-depth interviews with 50 so-called addicts.

As this work progressed, it developed into a full theoretical and empirical account of the nature of opiate addiction, culminating in his book Opiate Addictions in 1947 (republished as Addiction and Opiates in 1968).

What Lindesmith developed was an account of opiate addiction that (1) distinguished between the physical reactions of narcotic withdrawal and its psychological (phenomenological) experience, and (2) described the relationship between these two phenomena and addiction. Addressing the question of why regular users of opiates do not necessarily become dependent or addicted, he found that, while continuous opiate use does cause many to experience physical withdrawal, the impact of withdrawal on the likelihood of dependence and addiction is not certain. Lindesmith's "addicts" revealed this, in part, as did general reports from individuals who, despite regular use of opiates, failed to become habitual users, stressing "the advantage of attributing the origin of addiction, not to a single event, but to a series of events, thus implying that addiction is established in a learning process extending over a period of time."

This learning process has two parts. First, opiate users must connect their drug withdrawal to their use of the drug, which is something that individuals exposed to opiates in hospital settings are more likely to do. When withdrawal is interpreted as a form of addiction, the perceived (and felt) need for more drugs grows. More recent research has shown that, because hospital patients often associate opiate analgesia with an illness and/or hospital care, and because the drugs cause sedation and other mind-altering effects, patients rarely experience any withdrawal.

Here is the second part of the equation: if and when an opiate user identifies opiate withdrawal as such, he or she must initiate a ritual activity that is a physiological, cognitive, and behavioral mixture. As Richard DeGrandpre writes in The Cult of Pharmacology,[1] "the opiate user must first experience withdrawal (a physical phenomenon), he or she must develop a concern over the withdrawal experience as such (a cognitive phenomenon), and then he or she must engage in drug use, taking opiates repeatedly to eliminate or avoid opiate withdrawal (a behavioral phenomenon). A breakdown in any part of this bio-psycho-social circuit can keep a pattern of dependent opiate use from emerging."

In Robert Scharse's study of Mexican-American users, for example, some interpreted withdrawal as a sign of emerging drug dependence, and subsequently reduced or quit their drug use. For others, the withdrawal experience caused an obsession over the prospect of withdrawal, encouraging them to repeatedly use in order to avoid it. This then completed a circuit, with Lindesmith's learning process being reinforced and strengthened.

As his career ended, Lindesmith held on to his belief that opiate addiction is not the simple product of one's exposure to opiates. Rather it is the result of a dramatic shift in a person's mental and motivational state. Once the individual concludes that he or she is hooked, it rarely occurs to them that they are engaging in a self-fulfilling prophecy, trapped within a belief that makes the experience exactly what it is feared to be.

While Lindesmith's theory retains its canonical importance, it has been subject to several serious critiques. Lindesmith's theory of opiate addiction cannot explain relapse after physiological withdrawal symptoms have ceased and, more fundamentally, it relies on an outdated division of human perception into: (1) brute biological sensations the body passively experiences in immediate response to its physical environment, and (2) the mind's active and deliberate interpretation of those sensations. In short, Lindesmith's reliance on Herbert Blumer's voluntaristic understanding of meaning and interpretation profoundly undermined his capacity to theorize addiction as a loss of self-control, or as something suffered rather than chosen (Weinberg 1997).[2] For a debate of this critique see (Galliher 1998,[3] Weinberg 1998[4]).

War on drugs

The fact that Lindesmith's work threatened the emerging demonization of heroin, etc., is clear from how the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN)—predecessor of the DEA—worked to discredit him. This is outlined in a paper by Galliher, Keys, and Elsner, "Lindesmith v. Anslinger: An Early Government Victory in the Failed War on Drugs".[5] As early as 1939, FBN director Harry Anslinger had the Chicago District Supervisor of the Bureau notify Indiana University that one of their professors was a drug addict. An internal FBN memo also suggests that, some years later, a wire tap may have been placed on Lindesmith's phone by the Bureau. Incidentally, there is no evidence that Lindesmith ever used illegal drugs. As Galliher et al. point out, "the targeting of Lindesmith was possible because Lindesmith acted virtually alone in standing up against federal drug control policies."

In his book The Addict and the Law,[6] Lindesmith presents a detailed account of U.S. laws, regulations, police practices and court procedures, often in painful detail. He was describing what we now know as the beginning of the "war on drugs", although that term was not coined until 1971. It was published just 3 years after Anslinger retired. In his book, Lindesmith expressed hope that the relatively liberal drug policies of the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations would continue, but that was not to be.

Criticism

Professor Nils Bejerot argued that Lindesmith made wrong conclusions about what caused the low abuse of opium in the late 1940s in England. Lindesmith had noticed that England in the 1940s had very liberal narcotics laws (see the Rolleston Committee Report of 1924) and low drug abuse and draw the conclusion that the liberal drug laws contributed to a low abuse of opium. Drug addiction was by the Rolleston Committee seen as a personal problem that could be treated by a family doctor. Bejerot – who was very familiar with the discussion about drug policy in the UK and had studied epidemiology and medical statistics at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in 1963 – drew the opposite conclusion. He argued instead that the low number of drug abusers in England until the 1950s was the cause of liberal drug laws in England. When the number of addicts of heroin in England doubled every sixteenth months from 1959 to 1968, the British government was forced to implement more restrictive drug laws.[7][8][9][10]

Lindesmith wrote his earlier books from close personal interviews with a very limited number of addicts, about 50, almost all of them victims of therapeutic use of drugs when they were in health care for other reasons. Bejerot agreed with Lindesmith that these therapeutic addicts could be treated as personal health problems. These addicts were often ashamed of their drug abuse and the risk that they should introduce others in drug addiction was low. Bejerot claimed that persons from other, much larger, groups of drug addicts often were those that introduced others in their habit to use drugs (Bejerot studied this issue in his doctor thesis about persons who injected amphetamine). Bejerot claimed that the liberal drug laws that Lindesmith recommended – neglecting smaller amounts of illegal drugs for personal use etc. – therefore would open the doors for a much larger drug epidemic. Then, the society will rebound with much more restrictive laws (compare with the War on drugs).[9][11]

Lindesmith himself was a careful and conservative man, never using drugs or advocating their use.

Personal life

Lindesmith was born in Clinton Falls Township, Steele County, Minnesota, and gained an early fluency in German from his German-born mother. He attended public school in nearby Owatonna, Minnesota, where he graduated from high school in 1923. He graduated from Carleton College in 1927 and received an M.A. in education from Columbia University in 1931. Lindesmith taught school before entering the University of Chicago, where he received his Ph.D. in 1937, writing his dissertation under the direction of Herbert Blumer. In the development of his dissertation, Lindesmith applied the tenets of symbolic interactionism, communicated to him from Blumer before that perspective even had its present name. He was a close colleague of Edwin Sutherland, who chaired the Department of Sociology at Indiana until his death in 1950 and collaborated with luminaries in symbolic interaction such as Anselm Strauss, Howard Becker, and Edwin Lemert. Lindesmith's teaching career at Indiana University spanned forty years from 1936 to 1976. He became University Professor of Sociology there in 1965. He was president of the Society for the Study of Social Problems, 1959–1960.[12]

Lindesmith married Gertrude Louise Augusta Wollaeger (1907–1985) in 1930. They had one daughter. He died in Bloomington, Indiana.

In 1929, he was a professor and head football coach at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point.[13]

Head coaching record

| Year | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Bowl/playoffs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stevens Point Pointers (Wisconsin State Teachers College Conference) (1929) | |||||||||

| 1929 | Stevens Point | 0–6 | 0–4 | 10th | |||||

| Stevens Point: | 0–6 | 0–4 | |||||||

| Total: | 0–6 | ||||||||

References

- R. DeGrandpre, The Cult of Pharmacology: How America Became the World's Most Troubled Drug Culture. Durham: Duke University Press (2006).

- Weinberg, Darin. 1997. "Lindesmith on Addiction: A Critical History of a Classic Theory." Sociological Theory. 15(2): 150–161

- Galliher, John. 1998. "Comment on Weinberg's 'Lindesmith on Addiction'." Sociological Theory. 16(2): 205–206

- Weinberg, Darin. 1998. "Praxis and Addiction: A Reply to Galliher." Sociological Theory. 16(2): 207–208

- John F. Galliher, David P. Keys, Michael Elsner, "Lindesmith v. Anslinger: An Early Government Victory in the Failed War on Drugs." The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Vol. 88, No. 2 (Winter, 1998), pp. 661–682

- A.R. Lindesmith, The Addict and the Law. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (1965).

- Nils Bejerot: Narkotika och Narkomani, 1975

- Rachel Lart BRITISH MEDICAL PERCEPTION FROM ROLLESTON TO BRAIN, CHANGING IMAGES OF THE ADDICT AND ADDICTION Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Nils Bejerot & Jonas Hartelius Missbruk och motåtgärder, 1984

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-08-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Nils Bejerot:Narkotikafrågan och samhället, Stockholm, 1967,1969

- Information in this section was drawn from Karl Schuessler, "Dedication to Alfred R. Lindesmith, 1905–1991," in Harold Traver and Mark S. Gaylord (eds.), Drugs, the Law and the State, Edison, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1992, pp. xi-xiv. ISBN 1-56000-082-1; Rootsweb.com; the Birth Certificates Index of the Minnesota Historical Society; the 1910 U.S. Census; and the web sites of the Owatonna Alumni Association Archived 2010-07-04 at the Wayback Machine and the Society for the Study of Social Problems.

- The Iris (PDF). epapers.uwsp.edu. 1930. Retrieved February 8, 2018.