Amazon Reef

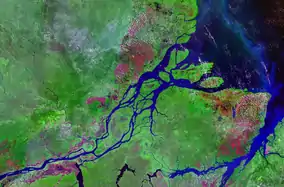

The Amazon Reef, or Amazonian Reef,[1] is an extensive coral and sponge reef system, located in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of French Guiana and northern Brazil. It is one of the largest known reef systems in the world, with scientists estimating its length at over 1,000 kilometres (600 miles), and its area as over 9,300 km2 (3,600 sq mi). Publication of its discovery was released in April 2016, following an oceanographic study of the region in 2012. Evidence of a large structure near the delta of the Amazon River dated from as early as the 1950s.

History

In the 1970s, the biologist Rodrigo Moura completed a study on fishing on the continental shelf and wanted to expand his research by locating the reefs where he caught the fish.[2] When Moura located the fish he caught around the Amazon Reef and in the mouth of the Amazon River, he saw this as an indication that there must be biodiversity underneath, as the fish was indicated to be a coral reef fish.[3][4] A few decades later a group of students from the University of Georgia noted that Moura's article did not contain GPS coordinates and used Moura's sound waves and sea floor samples to locate the reef.[2] Once they believed they had located the reef they dredged the bottom to confirm that this was its location.[3] The process of finding the reef took about three years before an official announcement was made about its discovery.[5]

The Amazon River is home to about 20 percent of the world's fresh water supply, placing the Amazon Reef at the mouth of the largest river in the world, where every day one fifth of the world's water flows into the ocean from the Amazon River.[5] Because of this, the Amazon Reef is less biologically diverse compared to other reefs of its kind.[4]

Geography and ecology

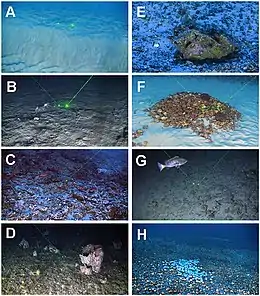

A: sand dunes in the shallowest portion of the reef (60–70 m or 200–230 ft)

B: reef covered by sediments between 70 and 80 m (230 and 260 ft) depth

C: diverse reef community with schools of Paranthias furcifer and bottom dominated by live crustose coralline algae and black corals at 130 m (430 ft) depth

D: deepest portion (220 m or 720 ft) with nearly 100% of live benthic coverage (mostly sponges, octocorals and black corals)

E: a cleaning station of Lysmata grabhami at 110 m (360 ft) depth

F: rhodolith mound built by Malacanthus plumieri at 130 m (430 ft) depth

G: a large snowy grouper (>60 cm total length) at 190 m (620 ft) depth

H: an urchin barren at 130 m (430 ft) depth

The reef system has been identified as a coral and sponge reef. Scientists estimated the reef's size to be 9,300 km2 (3,600 sq mi) in area, and over 970 km (600 mi) in length,[7][5][1] making it one of the largest reef systems in the world, comparable to the size of the island of Cyprus. Another estimate also puts the general ecoregion encompassing the reef to be as large as 14,000 km2 (5,592 sq mi).[8] The reef's area extends as far as 120 km (75 mi) offshore,[9] and is estimated to lie in waters ranging from 30 to 120 metres (100 to 400 feet) deep. The reef's existence is unusual, as reef systems do not often exist in the mouths of larger rivers like the Amazon, due to the low salinity and high acidity, in addition to the continuous rain of sediments.[10] Before the reef's discovery, it was originally believed that the Amazon, with its sediment-rich plume, represented a significant gap in reef distribution across the Western Atlantic,[11] correlating with the accepted view that corals thrived in clear waters along tropical shelves.[12] The reef primarily owes its existence to its depth, as it is below the freshwater layer of discharge from the Amazon into the Atlantic Ocean, a discharge that represents one fifth of the outflow into the Earth's oceans.[13][14]

The majority of the reef is made up of beds of rhodolith, various species of red algae, which superficially resemble coral.[8] While it has been described as "impoverished",[7] and "not having the biodiversity of some of the more prominent coral reefs of the world",[14] 61 species of sponge and 73 species of fish, in addition to various coral and starfish species, have so far been identified as inhabiting the reef,[15] including staghorn corals, and spiny lobsters.[16][17] Pockets of coral species, discovered as early as 1999, were found to be similar to those found in the Caribbean Sea, hinting at the possibility that Caribbean corals dispersed to the Amazon Reef.[9] Marine biologists have also entertained the idea that the reef serves as a stepping stone to facilitate dispersal of species from reefs in southern Brazil northwards to the Caribbean.[12] The biology of the reef is mostly dictated by the discharge of the Amazon into the Atlantic. Northern sections of the reef are often shrouded in the shadow of the sediment layer above for half a year on average, producing an environment similar to a "shadow zone".[8] These northern areas are populated with sponges and carnivorous species such as hydroids. Southern sections of the reef, which are covered by the Amazon's plume only three months a year on average, are more populated with diverse coral-centric life, where photosynthesis can occur.[5] It is believed that single-celled organisms are central to the reef's ecosystem, providing the main source of nutrients to sponges, corals and other inhabitants. Fabiano Thompson, along with other researchers on the reef, describe the system as a new class of biome.[8]

Discovery

Initial evidence for a coral and sponge reef system in the Amazon Delta region first surfaced in the late 1950s, when a U.S. survey ship collected sponges from the floor of the Amazon Delta.[18] Further evidence also appeared in 1977, when reef fish were first sighted in the area,[11][19] and in 1999, when Caribbean-native coral species were found in isolated regions near the Amazon Delta.[9] However, no major study into the existence of a reef system occurred until 2012, when an international research team of over 30 oceanographers,[13] led by Rodrigo Moura of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and including patrons from the University of Georgia,[11] conducted a survey of the area aboard the RV Atlantis. The survey was mostly based on findings from the 1970s, including a crude map of the area marked with potential locations of reefs along the Amazonian coast.[9] The team used technologies such as acoustic sampling to locate potential reef sites, and confirmed the discovery by dredging the floor of the reef, bringing up samples of corals, sponges and other reef species onto the ship deck. Their discoveries and findings were detailed and presented in a research article published in the scientific journal Science Advances in April 2016.[20]

Some of the waters in the Amazon Reef are considered to be some of the murkiest and muddiest waters around the world due to the Amazonian plume. Scientists have stated that the reef's biology is dependent on the location of the Amazonian plume. The southernmost area of the reef only contains the plume three months out of the year, while the northern area is covered by sponges and carnivorous sea life making it covered from the sunlight so that the area is shielded by the plume for six or more months out of the year.[5] From examining the reef's sea life, some of which are newly discovered, the scientists found that the reef is a split between the Brazilian reef and the Caribbean reef. They also found that as the southernmost part of the reef receives the most sun, it is also the area that the sea life uses to make their food.[2]

Environmental threats

Since its discovery, multiple environmental threats to the reef's ecosystem have been identified, including pollution and overfishing,[20] and rising ocean acidification and temperature as a result of recent acceleration in climate change, which also affects various reefs around the world.[16][15][21][22] A more immediate threat, however, are the numerous oil exploration projects operating nearby or on the reef itself.[23] In the past decade, the Brazilian government had sold 80 license blocks to oil energy companies in the region, with an environmental baseline based on "sparse museum specimens".[12] Twenty of these blocks are already producing oil.[7]

Climate change effects

The Amazon Reef is at risk of coral bleaching, an issue prevalent with other reefs such as the Great Barrier Reef located off the coast of Australia.[24]

References

- Stone, Maddie (April 22, 2016). "There's a Gigantic Reef Surrounding the Amazon River and Nobody Noticed". Gizmodo. Gawker Media. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Ghose, Tia (April 24, 2016). "Massive Coral Reef Discovered in the Amazon River". Live Science. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- Danigelis, Alyssa (April 26, 2016). "Enormous Coral Reef Discovered at Mouth of Amazon River". Seeker. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- Luntz, Stephen (April 24, 2016). "Astonishing Coral Reef Found At Amazon River's Mouth". IFLScience. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- Meyer, Robinson (April 21, 2016). "Scientists Have Discovered a 600-Mile Coral Reef". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- Francini-Filho, Ronaldo B.; Asp, Nils E.; Siegle, Eduardo; Hocevar, John; Lowyck, Kenneth; D'Avila, Nilo; Vasconcelos, Agnaldo A.; Baitelo, Ricardo; Rezende, Carlos E. (2018). "Perspectives on the Great Amazon Reef: Extension, Biodiversity, and Threats". Frontiers in Marine Science. 5. doi:10.3389/fmars.2018.00142. ISSN 2296-7745.

- Vidal, John (April 23, 2016). "Huge coral reef discovered at Amazon river mouth". The Guardian. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Viegas, Jennifer (April 23, 2016). "Unique coral reef ecosystem discovered in the Amazon river". Mashable. Discovery Communications. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Welch, Craig (April 22, 2016). "Surprising, Vibrant Reef Discovered in the Muddy Amazon". National Geographic. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Imam, Jareen (April 23, 2016). "Massive coral reef discovered in the Amazon River". CNN. Time Warner. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Flurry, Alan (April 22, 2016). "Scientists discover new reef system at mouth of Amazon River". Phys.org. Omicron Technology Limited. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Khan, Amina (April 22, 2016). "Scientists discover coral reef near the mouth of the Amazon River". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- MacDonald, Fiona (April 22, 2016). "Scientists just discovered a 1,000-km-long coral reef at the mouth of the Amazon". ScienceAlert. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Mendelsohn, Tom (April 23, 2016). "Scientists astonished by huge coral reef found in the Amazon". International Business Times. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Ciccarelli, Raffaella (April 24, 2016). "Huge coral reef growing at the mouth of the Amazon surprises scientists". news.com.au. News Corp Australia. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Yeung, Peter (April 24, 2016). "Scientists just discovered a hidden coral reef in the Amazon river and it's huge". The Independent. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Kennedy, Merrit (April 23, 2016). "Reef Larger Than Delaware Found At The Mouth Of The Amazon River". National Public Radio. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Nuwer, Rachel (April 22, 2016). "Shining Light on Brazil's Secret Coral Reef". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Bruce, Collette; Klaus, Ruetzler (1977). "Reef Fishes Over Sponge Bottoms Off the Mouth of the Amazon River". Food and Agriculture Organization. United Nations. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Moura, Rodrigo L.; Amado-Filho, Gilberto M.; Moraes, Fernando C.; Brasileiro, Poliana S.; Salomon, Paulo S.; Mahiques, Michel M.; Bastos, Alex C.; Almeida, Marcelo G.; Silva, Jomar M.; Araujo, Beatriz F.; Brito, Frederico P.; Rangel, Thiago P.; Oliveira, Braulio C. V.; Bahia, Ricardo G.; Paranhos, Rodolfo P.; Dias, Rodolfo J. S.; Siegle, Eduardo; Figueiredo, Alberto G.; Pereira, Renato C.; Leal, Camille V.; Hajdu, Eduardo; Asp, Nils E.; Gregoracci, Gustavo B.; Neumann-Leitão, Sigrid; Yager, Patricia L.; Francini-Filho, Ronaldo B.; Fróes, Adriana; Campeão, Mariana; Silva, Bruno S.; Moreira, Ana P. B.; Oliveira, Louisi; Soares, Ana C.; Araujo, Lais; Oliveira, Nara L.; Teixeira, João B.; Valle, Rogerio A. B.; Thompson, Cristiane C.; Rezende, Carlos E.; Thompson, Fabiano L. (April 1, 2016). "An extensive reef system at the Amazon River mouth". Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 2 (4): e1501252. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1252M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501252. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4846441. PMID 27152336.

- Handwerk, Brian; Hafvenstein, Lauri (March 25, 2003). "Belize Reef Die-Off Due to Climate Change?". National Grographic News. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Hannam, Peter (March 6, 2014). "Great Barrier Reef faced with irreversible damage". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Salmon, Natasha (April 23, 2016). "Scientists have made an incredible discovery on the Amazon River". Daily Mirror. Trinity Mirror. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- Kennedy, Merrit (April 10, 2017). "Great Barrier Reef Hit By Bleaching For The Second Year In A Row". NPR.org. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amazon Reef. |