Amniotic sac

The amniotic sac, commonly called the bag of waters,[1][2] sometimes the membranes,[3] is the sac in which the fetus develops in amniotes. It is a thin but tough transparent pair of membranes that hold a developing embryo (and later fetus) until shortly before birth. The inner of these fetal membranes, the amnion, encloses the amniotic cavity, containing the amniotic fluid and the fetus. The outer membrane, the chorion, contains the amnion and is part of the placenta. On the outer side, the amniotic sac is connected to the yolk sac, the allantois, and via the umbilical cord, the placenta.[4]

| Amniotic sac | |

|---|---|

10-week-old human fetus surrounded by amniotic fluid within the amniotic sac | |

| Anatomical terminology |

Amniocentesis is a medical procedure where fluid from the sac is sampled[5] to be used in prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal abnormalities and fetal infections.[6]

Structure

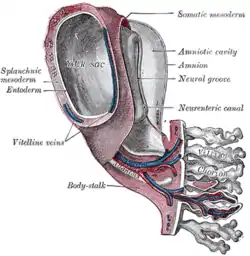

The amniotic cavity is the closed sac between the embryo and the amnion, containing the amniotic fluid. The amniotic cavity is formed by the fusion of the parts of the amniotic fold, which first makes its appearance at the cephalic extremity, and subsequently at the caudal end and sides of the embryo. As the amniotic fold rises and fuses over the dorsal aspect of the embryo, the amniotic cavity is formed.

Development

At the beginning of the second week, a cavity appears within the inner cell mass, and when it enlarges it becomes the amniotic cavity. The floor of the amniotic cavity is formed by the epiblast. Epiblast migrates between the epiblastic disc and trophoblast. In this way the epiblastic cells migrate between the embryoblast and trophoblast. The floor is formed by the epiblast which later on transforms to ectoderm while the remaining cells which are present between the embryoblast and trophoblast are called amnioblasts (flattened cells). These cells are also derived from epiblast which is transformed into ectoderm.

The amniotic cavity is surrounded by a membrane, called the amnion. As the implantation of the blastocyst progresses, a small space appears in the embryoblast, which is the primordium of the amniotic cavity. Soon, amniogenic (amnion forming cells) amnioblasts separate from the epiblast and line the amnion, which encloses the amniotic cavity.

The epiblast forms the floor of the amniotic cavity, and is continuous peripherally with the amnion. The hypoblast forms the roof of the exocoelomic cavity, and is continuous with the thin exocoelomic membrane. This membrane along with hypoblast forms the primary yolk sac. The embryonic disc now lies between the amniotic cavity and the primary yolk sac. Cells from the yolk sac endoderm form a layer of connective tissue, the extraembryonic mesoderm, which surrounds the amnion and yolk sac.

Birth

If, after birth, the complete amniotic sac or big parts of the membrane remain coating the newborn, this is called a caul.

When seen in the light, the amniotic sac is shiny and very smooth, but tough.

Once the baby is pushed out of the mother's uterus, the umbilical cord, placenta, and amniotic sac are pushed out in the after birth.

The amniotic sac opened during afterbirth examination

The amniotic sac opened during afterbirth examination

Function

The amniotic sac and its filling provide a liquid that surrounds and cushions the fetus. It is a site of exchange of essential substances, such as oxygen, between the umbilical cord and the fetus.[2] It allows the fetus to move freely within the walls of the uterus. Buoyancy is also provided.

Clinical significance

Chorioamnionitis is inflammation of the amniotic sac (chorio- + amnion + -itis), usually because of infection. It is a risk factor for neonatal sepsis.

During labor, the amniotic sac must break so that the child can be born. This is known as rupture of membranes (ROM). Normally, it occurs spontaneously at full term either during or at the beginning of labor. A premature rupture of membranes (PROM) is a rupture of the amnion that occurs prior to the onset of labor. An artificial rupture of membranes (AROM), also known as an amniotomy, may be clinically performed using an amnihook or amnicot in order to induce or to accelerate labour.

The amniotic sac has to be punctured to perform amniocentesis.[7][8] This is fairly routine procedure, but can lead to infection of the amniotic sac in a very small number of cases.[9] Infection more commonly arises vaginally.[9][10]

References

- Freshwater, Dawn; Masiln-Prothero, Sian (22 May 2013). Blackwell's Nursing Dictionary. ISBN 978-1118690871. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Jarzembowski, J. A. (1 January 2014), McManus, Linda M.; Mitchell, Richard N. (eds.), "Normal Structure and Function of the Placenta", Pathobiology of Human Disease, San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 2308–2321, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-386456-7.05001-2, ISBN 978-0-12-386457-4, retrieved 21 October 2020

- What is the amniotic sac?, NHS

- Larsen, WJ (2001). Human Embryology (3rd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. p. 40. ISBN 0-443-06583-7.

- The word amniocentesis itself indicates precisely the procedure in question, Gr. ἀμνίον amníon being the "inner membrane round the foetus" and κέντησις kéntēsis meaning "pricking", i.e. its puncture in order to retrieve some amniotic fluid.

- "Diagnostic Tests – Amniocentesis". Harvard Medical School. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- Wilde, Colin; Out, Dorothée; Johnson, Sara; Granger, Douglas A. (1 January 2013), Wild, David (ed.), "Chapter 6.1 - Sample Collection, Including Participant Preparation and Sample Handling", The Immunoassay Handbook (Fourth Edition), Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 427–440, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-097037-0.00029-4, ISBN 978-0-08-097037-0, retrieved 21 October 2020

- Carlson, Bruce M. (1 January 2014), Carlson, Bruce M. (ed.), "Chapter 18 - Fetal Period and Birth", Human Embryology and Developmental Biology (Fifth Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 453–472, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4557-2794-0.00018-8, ISBN 978-1-4557-2794-0, retrieved 21 October 2020

- Jefferson, Kimberly K. (1 January 2012), Sariaslani, Sima; Gadd, Geoffrey M. (eds.), "Chapter One - The Bacterial Etiology of Preterm Birth", Advances in Applied Microbiology, Academic Press, 80: 1–22, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-394381-1.00001-5, PMID 22794142, retrieved 21 October 2020

- Ariel, I.; Singer, D. B. (1 January 2014), McManus, Linda M.; Mitchell, Richard N. (eds.), "Placental Pathologies – Intrauterine Infections", Pathobiology of Human Disease, San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 2360–2376, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-386456-7.05007-3, ISBN 978-0-12-386457-4, retrieved 21 October 2020