Anne of the Thousand Days

Anne of the Thousand Days is a 1969 British period drama film based on the life of Anne Boleyn, directed by Charles Jarrott and produced by Hal B. Wallis. The screenplay by Bridget Boland and John Hale is an adaptation of the 1948 play of the same name by Maxwell Anderson.

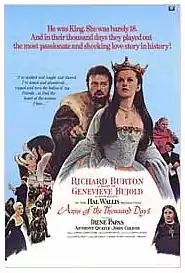

| Anne of the Thousand Days | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Charles Jarrott |

| Produced by | Hal B. Wallis |

| Screenplay by | Bridget Boland John Hale |

| Story by | Richard Sokolove |

| Based on | Anne of the Thousand Days by Maxwell Anderson |

| Starring | Richard Burton Geneviève Bujold Anthony Quayle John Colicos Irene Papas |

| Music by | Georges Delerue |

| Cinematography | Arthur Ibbetson |

| Edited by | Richard Marden |

Production company | Hal Wallis Productions |

| Distributed by | The Rank Organisation (UK) Universal Pictures (US) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 145 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $6,134,264 (US/Canada rentals)[1] |

The film stars Richard Burton as King Henry VIII and Canadian actress Geneviève Bujold as Anne Boleyn. Irene Papas plays Catherine of Aragon, Anthony Quayle plays Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, and John Colicos plays Thomas Cromwell. Others in the cast include Michael Hordern, Katharine Blake, Peter Jeffrey, Joseph O'Conor, William Squire, Vernon Dobtcheff, Denis Quilley, Esmond Knight, and T. P. McKenna, who later played Henry VIII in Monarch. Burton's wife Elizabeth Taylor makes a brief, uncredited appearance.

Despite receiving some negative reviews[2] and mixed reviews from The New York Times[3] and Pauline Kael,[4] the film was nominated for 10 Academy Awards and won the award for best costumes. Geneviève Bujold's portrayal of Anne, her first in an English language film, was very highly praised, even by Time magazine, which otherwise skewered the movie.[5] According to the Academy Awards exposé Inside Oscar, an expensive advertising campaign was mounted by Universal Studios that included serving champagne and filet mignon to members of the Academy following each screening.[6]

Plot

London, 1536. Henry VIII considers whether or not he should sign the warrant for the execution of his second wife, Anne Boleyn.

Nine years earlier, Henry has a problem: he reveals his dissatisfaction with his wife Catherine of Aragon. He is enjoying a discreet affair with Mary Boleyn, a daughter of one of his courtiers, Sir Thomas Boleyn; but the king is bored with her too. At a court ball, he notices Mary's 18-year-old sister Anne, who has returned from her education in France. She is engaged to the son of the Earl of Northumberland, and they have received their parents' permission to marry. The king, however, is enraptured with Anne's beauty and orders Cardinal Wolsey, his Lord Chancellor, to break the engagement.

When news of this decision is carried to Anne, she reacts furiously. She blames the cardinal and the king for ruining her happiness. When Henry makes a rather clumsy attempt to seduce her, Anne bluntly informs him how she finds him: "I've heard what your courtiers say, and I've seen what you are. You're spoiled and vengeful and bloody. Your poetry is sour, and your music is worse. You make love as you eat—with a good deal of noise and no subtlety."

Henry brings her back to court with him, and she continues to resist his advances out of a mixture of repugnance for Henry and her lingering anger over her broken engagement. However, she becomes intoxicated with the power that the king's love gives her. "Power is as exciting as love," she tells her brother George Boleyn, "and who has more of it than the king?" Using this power, she continually undermines Cardinal Wolsey, who at first sees Anne as a passing love interest for the king.

When Henry again presses Anne to become his mistress, she repeats that she never will give birth to a child who is illegitimate. Desperate to have a son, Henry suddenly comes up with the idea of marrying Anne in Catherine's place. Anne is stunned, but she agrees. Wolsey begs the king to abandon the idea because of the political consequences of divorcing Catherine. Henry refuses to listen.

When Wolsey fails to persuade the pope to give Henry his divorce, Anne points out this failing to an enraged Henry. Wolsey is dismissed from office, and his magnificent palace in London is given as a present to Anne. In this splendour, Anne realises that she has finally fallen in love with Henry. They sleep together, and after discovering that she is pregnant, they secretly are married. Anne is given a splendid coronation, but the people jeer at her in disgust as "the king's whore".

Months later, Anne gives birth to a daughter: Princess Elizabeth. Henry is displeased because he was hoping for a boy, and their marital relationship begins to cool. His attentions are soon diverted to Lady Jane Seymour, one of Anne's maids. Once she discovers this liaison, Anne banishes Jane from court. "She has the face of a simpering sheep," she informs Henry, "and the manners, but not the morals. I don't want her near me."

During a row over Sir Thomas More's opposition to Anne's queenship, Anne refuses to sleep with her husband unless More is put to death. "It's his blood, or else it's my blood and Elizabeth's!" she cries hysterically. More is put to death, but Anne's subsequent pregnancy ends, resulting in a stillborn boy.

Henry demands that his new minister Thomas Cromwell find a way to get rid of Anne. Cromwell tortures a servant in her household into confessing to adultery with the queen; he then arrests four other courtiers who are also accused of being Anne's lovers. Anne is taken to the Tower and placed under arrest. When she is told that she has been accused of adultery, she laughs. "I thought you were serious!" she says, and then she is informed that it is deadly serious. When she sees her brother being brought into the Tower, Anne asks why he has been arrested. "He too is accused of being your lover," mutters her embarrassed uncle. Anne's face shudders with horror before she whispers "Incest?... Oh, God help me, the king is mad. I am doomed."

At Anne's trial, she manages to cross-question Mark Smeaton, the tortured servant who finally admits that the charges against Anne are lies. Henry makes an appearance, then visits Anne in her chambers that night. He offers her freedom if she will agree to annul their marriage and make their daughter illegitimate. Anne refuses, saying that she would rather die than betray their daughter. Henry slaps her and tells her that her disobedience will mean her death.

Moving back to 1536, Henry decides to execute Anne. A few days later, Anne is taken to the scaffold and beheaded by a French swordsman. Henry rides off to marry Jane Seymour, and their young daughter, Elizabeth, toddling alone in the garden as she hears the cannon firing to announce her mother's death. Anne's voice is heard reciting a prophecy she spoke to Henry in the Tower: "Elizabeth shall be a greater queen than any king of yours. She shall rule a greater England than you could ever have built. My Elizabeth shall be queen, and my blood will have been well spent."

Cast

- Richard Burton as King Henry VIII

- Geneviève Bujold as Anne Boleyn

- Irene Papas as Queen Catherine of Aragon

- Anthony Quayle as Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

- John Colicos as Thomas Cromwell

- Michael Hordern as Thomas Boleyn

- Katharine Blake as Elizabeth Boleyn

- Valerie Gearon as Mary Boleyn

- Michael Johnson as George Boleyn

- Peter Jeffrey as Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk

- Joseph O'Conor as Bishop Fisher

- William Squire as Sir Thomas More

- Esmond Knight as Sir William Kingston

- Nora Swinburne as Lady Kingston

- Vernon Dobtcheff as Mendoza

- Brook Williams as Sir William Brereton

- Gary Bond as Mark Smeaton

- T. P. McKenna as Sir Henry Norris

- Denis Quilley as Sir Francis Weston

- Terence Wilton as Lord Percy

- Lesley Paterson as Jane Seymour

- Nicola Pagett as Princess Mary

- June Ellis as Bess

- Kynaston Reeves as Willoughby

- Marne Maitland as Cardinal Campeggio

- Cyril Luckham as Prior Houghton

- Amanda Jane Smythe as Princess Elizabeth

Elizabeth Taylor has an uncredited cameo appearance as a masked courtesan who interrupts Queen Catherine's prayers. Kate Burton makes her acting debut as a maid.

T. P. McKenna played the role of Henry VIII himself in the debut feature of John Walsh, titled Monarch.

Background and production

The play Anne of the Thousand Days, the film's basis, was first enacted on Broadway in the Shubert Theatre on 8 December 1948; staged by H.C. Potter, with Rex Harrison and Joyce Redman as Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn respectively, running 288 performances; Harrison won a Tony Award for his performance.

Cinematically, Anne of the Thousand Days took 20 years to reach the screen because its themes – adultery, illegitimacy, incest – were then unacceptable to the U.S. motion picture production code. The film was made on such locations as Penshurst Place and Hever Castle,[7] and at Pinewood and Shepperton Studios. Hever Castle was one of the main settings for the film; it was also the childhood home of Anne Boleyn.[8]

British actress Olivia Hussey was the first choice for the role of Anne Boleyn.[9] When producer Hal B. Wallis first met Hussey in New York in November 1967 at a party for her then upcoming film Romeo and Juliet (1968), he offered her the title role. In addition, he also offered her to star with John Wayne in True Grit (1969). In her 2019 memoir, Hussey stated that she had "mumbled something about being interested in Anne of the Thousand Days” but added that she "couldn’t see herself with Wayne". She claims that this "adolescent and opinionated" remark inevitably ended her professional relationship with Wallis, and he immediately withdrew his offer from her. "It had taken me less than a minute to talk my way out of it" Hussey stated.[10]

Maxwell Anderson employed blank verse for parts of his play, but most examples of this were removed from the screenplay. One blank verse episode that was retained was Anne's soliloquy in the Tower of London. The opening of the play was changed, with Thomas Cromwell's telling Henry VIII the outcome of the trial and Henry's recalling his marriage to Anne rather than Anne's speaking first and then Henry's remembering in flashback.[11]

Historical accuracy

- Historians dispute King Henry VIII's paternity of one or both of Mary Boleyn's children. Henry VIII: The King and His Court by Alison Weir questions the paternity of Henry Carey;[12] Dr. G.W. Bernard (The King's Reformation) and Joanna Denny (Anne Boleyn: A New Life of England's Tragic Queen) argue that Henry VIII was their father.

- Anne Boleyn might not have been 18 years old in 1527; her birth date is unrecorded. Most historians today believe that she must have been about 25 in 1527.

- There is no proof that Henry VIII ordered the breaking of Henry Percy and Anne Boleyn's engagement because he wanted Anne for himself. Percy's family, the Northumberlands, were one of the leading families in the North of England, and they always wanted Henry Percy to marry Mary Talbot, a rich heiress from the same region, and not a girl from a comparatively lower status family. They might have asked the king's and Cardinal Wolsey's intervention when the engagement was made public. In fact, in order to have no impediment for Henry VIII's and Anne's marriage, all parties always denied that any engagement had taken place.

- Most histories of the period say nothing about Anne's pressuring Henry to have More executed.

- Catherine of Aragon's daughter, Mary, was not present at the time of Catherine's final illness and death; they were being kept apart forcibly.

- Catherine of Aragon's depiction by Irene Papas was wrong in terms of appearance; it is well documented that the queen had auburn hair and a very pale complexion. Papas was chosen as she has a stereotypical Mediterranean appearance, matching false popular assumptions on how a 'Spanish' noble would look.

- The meeting between Anne and Henry shortly before her execution is fictional, and even if such a meeting had taken place, some details of their discussion are implausible. Anne's marriage was annulled anyway, and she never was offered a deal that would have given her her freedom. Elizabeth and Mary were both declared illegitimate, but were nevertheless in the line of succession, but not until after Anne's death. Thus, at that point, the chance of Elizabeth's inheriting the crown must have seemed small.

- Henry did not intervene in Anne's trial; she was disallowed the right to question the witnesses against her. She and the king met last at a joust the day before her arrest.

- Anne of the Thousand Days depicts Anne as innocent of the charges, and this depiction is considered historically correct per the biographies by Eric W. Ives, Retha Warnicke, Joanna Denny, and Tudor historian David Starkey, which all state her innocence of adultery, incest, and witchcraft.

Reception

The film received mixed reviews from critics, most commonly the plot was considered dull and plodding. Beyond the story itself, the performances of Geneviève Bujold, Richard Burton, and Irene Papas were met with universal acclaim, especially that of Bujold. Bujold remains the only actress nominated for an Oscar for playing Anne Boleyn.

The film was one of the more popular movies of 1970 at the British box office.[13]

Accolades

See also

References

- "Big Rental Films of 1970", Variety, 6 January 1971 p 11

- "Anne of the Thousand Days seems to have been made for one person: the Queen of England", Time Magazine

- Canby, Vincent (21 January 1970). "Screen: A Royal Battle of the Sexes:'Anne of 1,000 Days' Bows at Plaza Burton Cast as Henry Miss Bujold Stars". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.

- "Pauline Kael". www.geocities.ws.

- "Cinema: The Lion in Autumn". Time. 2 February 1970. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- Inside Oscar, Mason Wiley and Damien Boa, Ballantine Books (1986) pg. 434

- "Anne of the Thousand Days (1969) - IMDb" – via www.imdb.com.

- Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Anne of the Thousand Days Film Focus".

- Groucho. "Groucho Reviews: Interview: Olivia Hussey—Romeo and Juliet". Groucho Reviews. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Hussey, Olivia. The girl on the balcony : Olivia Hussey finds life after Romeo & Juliet (First Kensington hardcoverition ed.). pp. 84–85. ISBN 1496717074.

- Anne of the Thousand Days, Google books, accessed 15 April 2012

- Weir. Henry VIII: The King and His Court. p. 216.

- Harper, Sue (2011). British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure: The Boundaries of Pleasure. Edinburgh University Press. p. 269. ISBN 9780748654260.

- "The 42nd Academy Awards (1970) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 26 August 2011.

- "NY Times: Anne of the Thousand Days". NY Times. Retrieved 27 December 2008.