Antitrust (film)

Antitrust (also titled Conspiracy.com[4] and Startup[5]) is a 2001 techno thriller film written by Howard Franklin and directed by Peter Howitt.[6][7]

| Antitrust | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Howitt |

| Produced by | Nick Wechsler Keith Addis David Nicksay[1] |

| Written by | Howard Franklin |

| Starring | Ryan Phillippe Rachael Leigh Cook Claire Forlani Tim Robbins |

| Music by | Don Davis |

| Cinematography | John Bailey |

| Edited by | Zach Staenberg |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | MGM Distribution Co. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $18.2 million[3] |

Antitrust portrays young idealistic programmers and a large corporation (NURV) that offers a significant salary, an informal working environment, and creative opportunities for those talented individuals willing to work for them. The charismatic CEO of NURV (Tim Robbins) seems to be good-natured, but new employee and protagonist Milo Hoffman (Ryan Phillippe) begins to unravel the terrible hidden truth of NURV's operation.

The film stars Phillippe, Rachael Leigh Cook, Claire Forlani, and Robbins.[8] Antitrust opened in the United States on January 12, 2001, and was generally panned by critics.[7]

Plot

Working with his three friends at their new software development company Skullbocks, Stanford graduate Milo Hoffman is contacted by CEO Gary Winston of NURV (Never Underestimate Radical Vision) for a very attractive programming position: a fat paycheck, an almost-unrestrained working environment, and extensive creative control over his work. Accepting Winston's offer, Hoffman and his girlfriend, Alice Poulson (Forlani), move to NURV headquarters in Portland, Oregon.

Despite development of the flagship product (Synapse, a worldwide media distribution network) being well on schedule, Hoffman soon becomes suspicious of the excellent source code Winston personally provides to him, seemingly when needed most, while refusing to divulge the code's origin.

After his best friend, Teddy Chin, is murdered, Hoffman discovers that NURV is stealing the code they need from programmers around the world—including Chin—and then killing them to cover their tracks. Hoffman learns that not only does NURV employ an extensive surveillance system to observe and steal code, the company has infiltrated the Justice Department and most of the mainstream media. Even his girlfriend is a plant, an ex-con hired by the company to manipulate him.

While searching through a secret NURV database containing surveillance dossiers on employees, he finds that the company has information of a very personal nature about a friend and co-worker, Lisa Calighan (Cook). When he reveals to her that the company has this information, she agrees to help him expose NURV's crimes to the world. Coordinating with Brian Bissel, one of Hoffman's friends from his old startup, they plan to use a local public-access television station to hijack Synapse and broadcast their charges against NURV to the world. However, Calighan turns out to be a double agent, foils Hoffman's plan, and turns him over to Winston.

Hoffman had already confronted Poulson and convinced her to side with him against Winston and NURV. When it becomes clear that Hoffman has not succeeded, a backup plan is put into motion by Poulson, the fourth member of Skullbocks, and the incorruptible internal security firm hired by NURV. As Winston prepares to kill Hoffman, the second team successfully usurps one of NURV's own work centers—"Building 21"—and transmits the incriminating evidence as well as the Synapse code. Calighan, Winston and his entourage are publicly arrested for their crimes. After parting ways with the redeemed Poulson, Hoffman rejoins Skullbocks.

Cast

- Ryan Phillippe as Milo Hoffman

- Rachael Leigh Cook as Lisa Calighan

- Claire Forlani as Alice Poulson/Rebecca Paul

- Tim Robbins as Gary Winston

- Douglas McFerran as Bob Shrot

- Richard Roundtree as Lyle Barton

- Tygh Runyan as Larry Banks

- Yee Jee Tso as Teddy Chin

- Nate Dushku as Brian Bissel

- Ned Bellamy as Phil Grimes

- Tyler Labine as Redmond Schmeichel

- Scott Bellis as Randy Sheringham

- David Lovgren as Danny Solskjær

- Zahf Hajee as Desi

- Jonathon Young as Stinky

- Rick Worthy as Shrot's Assistant

- Peter Howitt as Homeless man

- Gregor Trpin as Computer Guy

Allusions

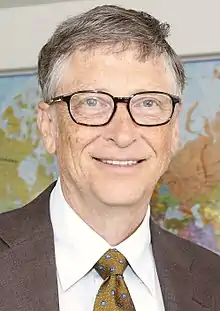

Roger Ebert found Gary Winston to be a thinly disguised pastiche of entrepreneur Bill Gates; so much so that he was "surprised [the writers] didn't protect against libel by having the villain wear a name tag saying, 'Hi! I'm not Bill!'" Similarly, Ebert felt NURV "seems a whole lot like Microsoft".[9] Parallels between the fictional and real-world software giants were also drawn by Lisa Bowman of ZDNet UK,[10] James Berardinelli of ReelViews,[11] and Rita Kempley of The Washington Post.[12] Microsoft spokesman Jim Cullinan said, "From the trailers, we couldn't tell if the movie was about [America Online] or Oracle."[10]

Production

Principal photography for Antitrust took place in Vancouver, British Columbia, California, and Portland, Oregon.[7][13]

Stanley Park in Vancouver served as the grounds for Gary Winston's house, although the gate house at its entrance was faux. The exterior of Winston's house itself was wholly computer-generated; only the paved walkway and body of water in the background are physically present in the park.[14] For later shots of Winston and Hoffman walking along a beach near the house, the CG house was placed in the background of Bowen Island, the shooting location.[15] Catherine Hardwicke designed the interior sets for Winston's house, which featured several different units, or "pods", e.g., personal, work, and recreation units. No scenes take place in any of the personal areas, however; only public areas made it to the screen.[16] While the digital paintings in Winston's home were created with green screen technology, the concept was based on technology that was already available in the real world. The characters even refer to Bill Gates' house which, in real life, had such art.[17] The paintings which appeared for Hoffman were of a cartoon character, "Alien Kitty", developed by Floyd Hughes specifically for the film.[18][19]

Simon Fraser University's Burnaby campus stood in for external shots of NURV headquarters.[20][21]

The Chan Centre for the Performing Arts at the University of British Columbia (UBC) was used for several internal locations. The centre's foyer area became the NURV canteen; the set decoration for which was inspired by Apple's canteen, which the producers saw during a visit to their corporate headquarters.[22] The inside of the Chan—used for concerts—served as the shape for "The Egg", or "The NURV Center", where Hoffman's cubicle is located.[23] Described as "a big surfboard freak" by director Peter Howitt, production designer Catherine Hardwicke surrounded "The Egg" set with surfboards mounted to the walls; Howitt has said, "The idea was to make NURV a very cool looking place."[21][24] Both sets for NURV's Building 21 were also on UBC's campus. The internal set was an art gallery on campus, while the exterior was built for the film on the university's grounds. According to Howitt, UBC students kept attempting to steal the Building 21 set pieces.[25]

Hoffman and Poulson's new home—a real house in Vancouver—was a "very tight" shooting location and a very rigorous first week for shooting because, as opposed to a set, the crew could not move the walls.[26] The painting in the living room is the product of a young Vancouver artist, and was purchased by Howitt as his first piece of art.[27]

The new Skullbocks office was a real loft, also in Vancouver, on Beatty Street.[28]

Open source

Antitrust's pro–open source story excited industry leaders and professionals, with the prospects of expanding the public's awareness and knowledge level of the availability of open-source software. The film heavily features Linux and its community, using screenshots of the Gnome desktop, consulting Linux professionals, and including cameos by Miguel de Icaza and Scott McNealy (the latter appearing in the film's trailers). Jon Hall, executive director of Linux International and consultant on the film, said "[Antitrust] is a way of bringing the concept of open source and the fact that there is an alternative to the general public, who often don't even know that there is one."[10]

Despite the film's message about open source computing, MGM did not follow through with their marketing: the official website for Antitrust featured some videotaped interviews which were only available in Apple's proprietary QuickTime format.[10]

Reception

Antitrust received mainly negative reviews, and has a "Rotten" consensus of 24% on Rotten Tomatoes, based on 106 reviews, with an average score of 4 out of 10. The summary states "Due to its use of clichéd and ludicrous plot devices, this thriller is more predictable than suspenseful. Also, the acting is bad."[29] The film also has a score of 31 out 100, based on 29 reviews, on Metacritic.[30]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film two stars out of four.[9] Linux.com appreciated the film's open-source message, but felt the film overall was lackluster, saying "'AntiTrust' is probably worth a $7.50 ticket on a night when you've got nothing else planned."[31]

James Keith La Croix of Detroit's Metro Times gave the film four stars, impressed that "Antitrust is a thriller that actually thrills."[32]

The film won both the Golden Goblet for "Best Feature Film", and "Best Director" for Howitt, at the 2001 Shanghai International Film Festival.[33]

Home media

Antitrust was released as a "Special Edition" DVD on May 15, 2001,[34] and on VHS on December 26, 2001.[35] The DVD features audio commentary by the director and editor, an exclusive documentary, deleted scenes and alternative opening and closing sequences with director's commentary, Everclear's music video for "When It All Goes Wrong Again" (which is played over the beginning of the closing credits), and the original theatrical trailer. The DVD was re-released August 1, 2006.[36] It was released on Blu-ray Disc on September 22, 2015.[37]

See also

- List of films featuring surveillance

- Hackers (1995 film)

- The Circle (2017 film)

References

Citations

- "AFI|Catalog".

- "ANTITRUST (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 2001-02-08. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- "Antitrust (2001)". Box Office Mojo. Box Office Mojo LLC. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "conspiracy.com" (in German). OutNow.CH. 2001-02-06. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "Filmlexikon FILME von A-Z - startup" (in German). Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "Antitrust (2001) - Cast and Credits". Yahoo! Movies. Yahoo Inc. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "Antitrust (2001) - Movie Details". Yahoo! Movies. Yahoo Inc. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "Antitrust (2001) - Movie Info". Yahoo! Movies. Yahoo Inc. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- Ebert, Roger (January 12, 2001). "Antitrust". suntimes.com. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- Bowman, Lisa (2001-01-08). "Linux to star on silver screen". ZDNet UK. CNET Networks, Inc. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- Berardinelli, James (2001). "Review: Antitrust". ReelViews. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- Kempley, Rita (2001-01-12). "'Antitrust': Battling the Evil Geek". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- "Filmed in Oregon 1908-2015" (PDF). Oregon Film Council. Oregon State Library. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- Howitt (commentary), 07:51

- Howitt (commentary), 13:04

- Catherine Hardwicke (2001-05-15). Antitrust, "Cracking the Code" (DVD documentary). Los Angeles, California, USA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Event occurs at 10:02.

- Zach Staenberg (2001-05-15). Antitrust (DVD commentary). Los Angeles, California, USA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Event occurs at 10:02.

- Howitt (commentary), 1:16:37

- Antitrust (motion picture). Los Angeles, California, United States: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 2001-01-12.

- "SFU in films and television". SFU.ca. Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original on 2008-01-15. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- Howitt (commentary), 17:28

- Howitt (commentary), 18:57

- Howitt (commentary), 19:30

- Howitt (commentary), 20:23

- Howitt (commentary), 51:06

- Howitt (commentary), 23:56

- Howitt (commentary), 01:10:23

- Howitt (commentary), 26:09

- "Antitrust". rottentomatoes.com. 12 January 2001.

- "Antitrust". Metacritic.

- Gross, Grant (January 13, 2001). "Open Source, the movie: 'AntiTrust' reviewed". Linux.com. Sourceforge Inc. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- La Croix, James Keith (January 17, 2001). "Antitrust". Metro Times. Detroit, Michigan, USA: Times-Shamrock Communications. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- "Golden Goblet Winners" Archived May 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. 2001 Shanghai International Film Festival. Retrieved 2012-12-14.

- "Antitrust (2001)". Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- "Antitrust (2000)". Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- "Antitrust - Special Edition (DVD)". CinemaClock Canada Inc. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Antitrust Blu-ray, retrieved 2018-11-02

Video sources

- Peter Howitt (2001-05-15). Antitrust (DVD commentary). Los Angeles, California, USA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Antitrust (film) |