Anurognathidae

Anurognathidae is a family of small pterosaurs, with short or absent tails, that lived in Europe, Asia, and possibly North America during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Five genera are known: Anurognathus, from the Late Jurassic of Germany; Jeholopterus, from the Middle to Late Jurassic of China;[1] Dendrorhynchoides, from the Middle Jurassic[2] of China; Batrachognathus, from the Late Jurassic of Kazakhstan; and Vesperopterylus, from the Early Cretaceous of China.[3] Bennett (2007) claimed that the holotype of Mesadactylus, BYU 2024, a synsacrum, belonged to an anurognathid.[4] Mesadactylus is from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the United States. Indeterminate anurognathid remains have also been reported from the Middle Jurassic Bakhar Svita of Mongolia[5][6] and the Early Cretaceous of North Korea.[7]

| Anurognathids | |

|---|---|

| |

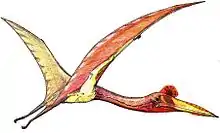

| Life restoration of Anurognathus ammoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Clade: | †Caelidracones |

| Family: | †Anurognathidae Nopcsa, 1928 |

| Type species | |

| †Anurognathus ammoni Döderlein, 1923 | |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Classification

A family Anurognathidae was named in 1928 by Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás (as the subfamily Anurognathinae) with Anurognathus as the type genus. The family name Anurognathidae was first used by Oskar Kuhn in 1967. Both Alexander Kellner and David Unwin in 2003 defined the group as a node clade: the last common ancestor of Anurognathus and Batrachognathus and all its descendants.

The phylogeny of the Anurognathidae is uncertain. Some analyses, as those of Kellner, place them very basal in the pterosaur tree. However, they do have some characteristics in common with the derived Pterodactyloidea, such as the short and fused tail bones. In 2010 an analysis by Brian Andres indicated the Anurognathidae and the Pterodactyloidea were sister taxa. This conforms better to the fossil record because no early anurognathids are known and would require a ghost lineage of over sixty million years.[8]

Lifestyle

Anurognathids are often believed to have been nocturnal or crepuscular akin to bats. The fact that many anurognathids have large eye-sockets supports the theory of living in darkness. Anurognathid teeth suggest they were insectivorous, though some may have had more prey-choices, such as Jeholopterus who is also believed to have been a fish-eater. At least some, such as Vesperopterylus, were arboreal, with claws suited for gripping tree branches.[3]

Feathers

A study of pair of anurognathid specimens purported to show that that pterosaur pycnofibers were actually proto-feathers. These include at least four types, ranging from simple monofilaments to down-like structures and branched whiskers.[9] However, these were later disputed, with other authors suggesting that the supposed branching actually were taphonomic artefacts, stating that "When bunched up, or partially decomposed and unravelled, structural fibres (aktinofibrils) in the wing membranes of pterosaurs exhibit a variety of seemingly branched morphologies including brush-like and tuft-like structures".[10]

Notes

- Gao, K. -Q.; Shubin, N. H. (2012). "Late Jurassic salamandroid from western Liaoning, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (15): 5767–72. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009828109. PMC 3326464. PMID 22411790.

- Lü Junchang & David W.E. Hone (2012). "A New Chinese Anurognathid Pterosaur and the Evolution of Pterosaurian Tail Lengths". Acta Geologica Sinica. 86 (6): 1317–1325. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12002.

- Lü, J.; Meng, Q.; Wang, B.; Liu, D.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Y. (2017). "Short note on a new anurognathid pterosaur with evidence of perching behaviour from Jianchang of Liaoning Province, China". In Hone, D.W.E.; Witton, M.P.; Martill, D.M. (eds.). New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology (PDF). Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455. London: The Geological Society of London. doi:10.1144/SP455.16.

- Bennett, S. C. (2007). "Reassessment of Utahdactylus from the Jurassic Morrison Formation of Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(1): 257–260

- Unwin, D. M. & Bakhurina, N. N. (2000): Pterosaurs from Russia, Middle Asia and Mongolia. – In: M. J. Benton, M. A. Shishkin, D. M. Unwin & E. N. Kurochin (Eds), The age of dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia; Cambridge (Cambridge University Press), 420–433.

- Barrett, P.M., Butler, R.J., Edwards, N.P., & Milner, A.R. Pterosaur distribution in time and space: an atlas. p61-107. in Flugsaurier: Pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer. 2008. Hone, D.W.E., and Buffetaut, E. (eds). Zitteliana B, 28. 264pp.

- Gao, K.-Q.; Li, Q.-G.; Wei, M.-R.; Pak, H.; Pak, I. (2009). "Early Cretaceous birds and pterosaurs from the Sinuiju Series, and geographic extension of the Jehol Biota into the Korean Peninsula". Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea. 25 (1): 57–61. ISSN 1225-0929.

- Brian Andres; James M. Clark & Xu Xing (2010). "A new rhamphorhynchid pterosaur from the Upper Jurassic of Xinjiang, China, and the phylogenetic relationships of basal pterosaurs", Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Volume 30, Issue 1 January 2010 , pages 163 - 187

- Benton, Michael J.; Xu, Xing; Orr, Patrick J.; Kaye, Thomas G.; Pittman, Michael; Kearns, Stuart L.; McNamara, Maria E.; Jiang, Baoyu; Yang, Zixiao (2019-01). "Pterosaur integumentary structures with complex feather-like branching". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0728-7. ISSN 2397-334X.

- Unwin, David M.; Martill, David M. (December 2020). "No protofeathers on pterosaurs". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (12): 1590–1591. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-01308-9. ISSN 2397-334X.