Artistic development of Tom Thomson

Tom Thomson (1877–1917) was a Canadian painter from the beginning of the 20th century. Beginning from humble roots, his development as a career painter was meteoric, only pursuing it seriously in the final years of his life. He became one of the foremost figures in Canadian art, leaving behind around 400 small oil sketches and around fifty larger works on canvas.

Beginning his career in 1902 as a graphic designer, he only began to paint seriously in 1912 at the age of 35. His skills developed as he ventured through Algonquin Park, sketching scenes that interested him. His creative peak came from 1914 until his untimely death in 1917. His art style progressed from sombre, grey scenes into brilliantly coloured exposés, characterized by rapid and thickly applied brushstrokes. His later works presage the advances seen by the Abstract Expressionist movement.

Materials and working method

Sketch to canvas

The artwork of Thomson is typically divided into two bodies: the first is made up of the small oil sketches on wood panels, of which there are around 400, and the second is of around fifty larger works on canvas.[2] The smaller sketches were typically done in the style of en plein air in "the North," primarily Algonquin Park, in the spring, summer and fall.[3] The larger canvases were instead completed over the winter in Thomson's studio—an old utility shack with a wood-burning stove on the grounds of the Studio Building, an artist's enclave in Rosedale, Toronto.[4][5][6] Although he sold few of the larger paintings during his lifetime, they formed the basis of posthumous exhibitions, including one at Wembley in London, that eventually brought international attention to his work,[7] though the more plentiful sketches have typically been thought of as the core of his work.[1]

He considered most of his sketches to be complete works in themselves and not studies for larger works, since in the transition to a larger canvas the works lose their characteristic intimacy.[1] Still, a dozen or so of the major canvases were directly derived from smaller sketches. Indeed, paintings like Northern River, Spring Ice, The Jack Pine and The West Wind were only later expanded into larger oil paintings.[2] While the sketches were produced quickly, the canvases were developed over weeks or even months. Because of this, they display an "inherent formality," with the transition from small to large requiring a reinvention or elaboration of the original details.[8] In this transition he often exaggerated hillsides or other landscape features to give the final picture greater depth.[9] Comparing sketches with their respective canvases allows one to see the changes Thomson made in colour, detail and background textural patterns.[10][11]

Materials

In 1914 Thomson made himself a sketch box to hold 8½ × 10½ inch (21.6 × 26.7 cm) panels.[12] The lower half of the box served as a palette, while the upper half served as a support for canvas or wood panels. Slots made room for three paintings to be carried at any given time, keeping them apart so wet paint did not smear or flatten.[13] Thomson utilized different materials throughout his career, providing a method for dating paintings.[14] For example, the wood panels he used in 1914 developed vertical cracks.[15][14] He had only occasionally used hard wood-pulp board in 1914, but consistently began using it in 1915.[16] In the spring and fall of 1915 he used terra cotta-coloured and carnation-coloured paint as sealers, but by 1916 he had switched to ochre paint.[14] In the spring of 1917 he disassembled and cut up wood crates to make into 5 × 7 inch (12.7 × 17.8 cm) panels for sketching,[14][17] smaller than those he normally painted on and requiring tighter handling.[18] Fragments of brand names (e.g. Gold Medal Purity Flour, California Oranges) are stamped on the back of some,[19] such as Birches and An Ice Covered Lake.[20] During the same spring he reused around one-third of his sketches, either because he was not satisfied with them or because he was short on painting materials.[21]

In 2000, a study was conducted to understand the materials and working method of Thomson.[22] In 2002–03, before a travelling exhibition organized by the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Canadian Conservation Institute utilized infrared and X-ray photography, spectroscopy and micro-sampling of pigments to further analyze many of Thomson's paintings.[23] Sandra Webster-Cook and Anne Ruggles described in their research how Thomson applied differently coloured primers in various parts of his paintings to give them subtle yet important qualities.[24]

Photography

Thomson occasionally used photography to capture things that gained his interest, such as fish he caught, images of his friends or the landscape. He does not seem to have used any of his photographs for producing art, with none of the extant photos corresponding to any of his paintings.[25] He instead preferred to capture images with small oil sketches, and nearly all of the works he produced are among these small sketches.[26] David Silcox however has speculated that Drowned Land (and perhaps other paintings) may have been painted with a photograph as a memory aid given their "uncanny precision."[27][note 1]

In 1912 while travelling up the Spanish River in the Mississagi area with William Broadhead, Thomson lost at least a dozen rolls of film (claiming in a letter that he lost 14 dozen) along with many more sketches after their canoe experienced several spills.[28][29][30] He had intended to bring the images back to Grip Limited and use them in his commercial work.[26]

A lake in Southern Ontario, III, c. 1911. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

A lake in Southern Ontario, III, c. 1911. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa Scarborough Bluffs, II, c. 1912. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Scarborough Bluffs, II, c. 1912. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa Double exposure: northern lake, I, c. 1912. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Double exposure: northern lake, I, c. 1912. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa Two trout hanging from the tent pole, c. 1914. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Two trout hanging from the tent pole, c. 1914. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa Miss Winifred Trainor, II, c. 1913-17. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Miss Winifred Trainor, II, c. 1913-17. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Developments

Commercial art

Tom Thomson's first foray into art came in 1901 with his education at Canada Business College in Chatham, Ontario. It was there that he developed rudimentary penmanship abilities.[31][32] By 1902, he had been hired in Seattle at the design firm Maring & Ladd, working as a pen artist, draftsman and etcher.[31][32][33] His main work there consisted in producing business cards, brochures and posters, as well as three-colour printing.[32][33] Having previously learned calligraphy, he specialized in lettering, drawing and painting.[33] Thomson may have also worked as a freelance commercial designer, but there are no extant examples of such work to confirm these suspicions.[34] He was greatly influenced by the black and white illustrations he saw in magazines,[35] something especially apparent in his c. 1903 sketch, Study of a Woman's Head, which draws inspiration from the "Gibson Girl" of American illustrator Charles Dana Gibson.[36] Thomson's younger brother Ralph wrote about Thomson during this period:

[I had] a wonderful opportunity to observe his progress as a commercial artist and designer. He very often worked all night long while I watched him try one idea after another. The ones that did not meet with his approval he would either throw in the waste basket, burn up or smear with cigar ashes or the ends of burned matches. Others he would keep for a day or two but they would invariably meet the same fate. At that time he worked in pen and ink, water color and black and white wash. He was continually looking over the various magazines and giving the advertisements a great deal of study, principally from the standpoint of decoration. It was a regular game with him to pick the best of them, change the entire design to suit his own ideas, and then compare their respective merits.[34][37]

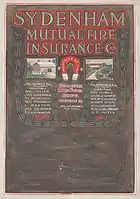

After returning to Toronto, Thomson joined the artistic design firm Grip Ltd. in either 1908 or 1909.[note 2] The firm specialized in design and lettering work.[31][32][40] Grip was the leading graphic design company in the country and introduced Art Nouveau, metal engraving and the four-colour process to Canada.[43] Albert Robson, then the art director at Grip, recalled that when he first hired Thomson, "his samples consisted mostly of lettering and decorative designs applied to booklet covers and some labels."[38][44]

The techniques he learned regarding Art Nouveau became apparent in many of his later works,[45][46] including paintings like Northern River; Decorative Landscape, Birches; Spring Ice and The West Wind.[47][48] Of particular note are the sinuous forms typical within the art style,[49] seen in the "S-curves" of the trees which have their origins in Thomson's work as a draughtsman.[50] Fellow artist A. Y. Jackson affirmed the Group of Seven's tendency towards using Art Nouveau styles within their work, writing that, "We (the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson) treated our subjects with the freedom of designers. We tried to emphasize colour, line and pattern."[51][52]

The senior artist at Grip, J. E. H. MacDonald, encouraged his staff to paint outside in their spare time to better hone their skills.[53][54] MacDonald had perhaps the largest influence on Thomson's career as a painter; he enticed Thomson away from the commercial field and brought him towards painting through not only the encouraged weekend outdoor sketching, but through painting trips on holidays and introducing him to his fellow artists.[55] MacDonald himself credited William Broadhead with Thomson's emergence as a painter, writing in a letter to Arthur Lismer that "My memories in connection with Tom seem to begin with B[roadhead]."[56] In a draft of an article, Harold Mortimer-Lamb similarly credited Broadhead with Thomson's emergence.[56][57] Lismer took exception to their claims, instead crediting MacDonald.[58] A. Y. Jackson also expressed that Thomson's major development came after his ventures to Algonquin Park, rather than his time as a graphic designer.[56][59][60] Lismer later wrote,

[J. E. H.] MacDonald was the most important influence on Tom Thomson at this stage. These young artists (MacDonald, Frank Johnston, Tom McLean, Frederick Varley, Franklin Carmichael and Lismer) worked hard all week and sketched on Saturdays and Sundays. On Monday it was MacDonald in his corner seat who gave his opinion on sketches and offered philosophical encouragement. He was already recognized as a Canadian artist. Thomson in 1911 had not tried his hand at sketching out of doors. Perhaps it was that hitherto he did not feel he could do anything with the medium of oil painting, or... he was not ready to emerge. It was in the summer and fall 1911 that Thomson first emerged as a sketcher. His first efforts were primitive. They had a child[-like] quality, but like a child's work, with good quality and character. It was in the country around Toronto, on the Humber River, in the bush near York Mills and on excursions into the country around Lindsay and L[ake] Scugog where he and others went fishing that Thomson first painted.[61][62]

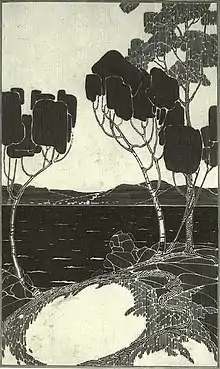

Decorative Landscape - Blessing by Robert Burns, c. 1907. Private collection.

Decorative Landscape - Blessing by Robert Burns, c. 1907. Private collection. Advertisement for the Sydenham Mutual Fire Insurance, Owen Sound, 1910. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Advertisement for the Sydenham Mutual Fire Insurance, Owen Sound, 1910. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound Near Owen Sound, November 1911. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Near Owen Sound, November 1911. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

First ventures to Algonquin Park (1912–13)

It was in 1912 that Thomson's transition from commercial art towards his original style of painting became apparent.[63][64] This transition appears to have been instigated by his first visit to Algonquin Park in May 1912.[65] He acquired his first sketching equipment,[56] but spent most of his trip fishing,[66] save for "a few notes, skylines and colour effects."[56][67] Dating sketches to this trip has sometimes proved difficult.[68] One exception is the sketch Smoke Lake, Algonquin Park, easily dated because Thomson gave it to Bud Callighen around the time of their first meeting.[69][70][71] Charles Hill has also included the "somewhat awkward" Old Lumber Dam, Algonquin Park as likely being made during the trip.[72] Robson identified Drowned Land as being painted on the Mississagi Forest Reserve canoe trip.[73] Also dated to this time are The Canoe and A Northern Lake (1912).[72]

Smoke Lake, Algonquin Park, Spring 1912. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Smoke Lake, Algonquin Park, Spring 1912. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound Old Lumber Dam, Algonquin Park, Spring 1912. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Old Lumber Dam, Algonquin Park, Spring 1912. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa The Canoe, Spring or fall 1912. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

The Canoe, Spring or fall 1912. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto A Northern Lake, Spring or fall 1912. Camp Tanamakoon, Algonquin Park

A Northern Lake, Spring or fall 1912. Camp Tanamakoon, Algonquin Park

In fall 1912 Thomson left Grip Ltd. to join another design firm, Rous & Mann.[74][53][75] Leonard Rossell went on to write, "Those who worked there were all allowed time off to pursue their studies... Tom Thomson, so far as a I know, never took definite lessons from anyone, yet he progressed quicker than any of us. But what he did was probably of more advantage to him. He took several months off in the summer and spent them in Algonquin Park."[76][44]

In October 1912 Thomson was first introduced to Dr. James MacCallum, a frequent visitor of the Ontario Society of Artists' (OSA) exhibitions and The Arts and Letters Club of Toronto.[68][77] MacCallum convinced Thomson to leave his position at Rous and Mann and commit to a career in painting.[74] Lawren Harris later recalled Thomson's major developments around this time:

Thomson began to develop. His work commenced to emerge into the clear Canadian daylight. His work had been tight and sombre, almost a grey monotone in colour. [A. Y.] Jackson's sparkling, vibrant, rich colour opened his eyes, as it did the eyes of the rest of us, and Tom saw the Canadian landscape as he had never seen it before. It amounted to a revelation. From then on nothing could hold him.[78][79]

MacCallum offered to cover Thomson's expenses for a year on the promise that he fully committed himself to painting,[80][81] an offer Thomson eventually accepted after some initial hesitance.[60] MacCallum wrote that when he first saw Thomson's sketches, he recognized their "truthfulness, their feeling and their sympathy with the grim fascinating northland... they made me feel that the North had gripped Thomson as it had gripped me since I was eleven when I first sailed and paddled through its silent places." He further wrote that Thomson's paintings were "dark, muddy in colour, tight and not wanting in technical defects."[82]

Thomson's ventures to the wilderness of Ontario were major sources of inspiration in his art, writing in a letter to MacCallum that the beauty of Algonquin Park was indescribable.[83] His early works, such as Northern Lake (1912–13) and Evening were not outstanding technically, yet they illustrate a particular talent for composition and colour handling.[84] The sale of the former to the Ontario Government in March 1913 for $250 (equivalent to CAD$5,600 in 2018) allowed him to spend more time in the summer and fall of 1913 sketching.[72][85][50] MacCallum described the painting as a "picture [of] one of the small northern lakes swept by a north west wind; a squall just passing from the far shore, the water crisp, sparkingly blue & broken into short, white-caps—a picture full of light, life and vigour."[82] Thomson's sketches from 1913 are often grey, but display greater colour handling than that seen in the earlier sketch of Northern Lake.[84] Most of these sketches are simple with a far off shore.[13] Canvases like Morning Cloud and Moonlight use broken brushwork, a technique he likely learned from MacDonald and Jackson.[13]

Northern Lake, Winter 1912–13. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Northern Lake, Winter 1912–13. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Autumn, Algonquin Park, Fall 1913. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Autumn, Algonquin Park, Fall 1913. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Morning Cloud, Winter 1913-14. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Morning Cloud, Winter 1913-14. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Moonlight, Winter 1913-14. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Moonlight, Winter 1913-14. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Colour and experimentation (1914–15)

Thomson often experienced self-doubt, with A. Y. Jackson recalling that in the fall of 1914, Thomson threw his sketch box into the woods out of frustration,[86][87] and was "so shy he could hardly be induced to show his sketches."[88] While his work from this period still displays "a certain awkwardness," Thomson surpassed his colleagues Jackson and Lismer in his brilliance of colour.[89] In a letter to MacCallum, Jackson wrote,

Tom seems quite enthusiastic and I expect is quite an inspiring man to work with. You need a man with you who tries to do the impossible. To do what you know is easily within your powers never has given rise to a great school of art or anything else.[90]

The sketches produced in 1915 display his increasing tendency towards experimentation and his sensitivity to colour,[91] experimenting with texture and colour in ways that his earlier subdued and precise work had avoided.[89] Beyond his work as a colourist, he developed a technique of presenting contradictory ideas that were simultaneously resolved within the same image. Typically he accomplished this by using the techniques of both Tonalism and Post-Impressionism, later achieving it by joining decorative patterns with bold handling.[92] Jackson wrote regarding this period of Thomson's work, "No longer handicapped by literal representation, he was transposing, eliminating, designing, experimenting, finding happy colour motives amid tangle and confusion and [reveling] in paint. The amount of work he did was incredible."[93]

Over the 1915–16 winter in Toronto, Thomson produced several canvases, including In the Northland; The Birch Grove, Autumn; Autumn's Garland; Opulent October and Spring Ice. The sketches of his work display a two-dimensionality. Thomson's work from this period—like the works of Harris, Lismer and MacDonald—became more decorative. The colour is heightened, with spaces flattened and forms arranged into vertical bands. The branches and trunks of trees are more stylized in nature.[94]

Soft Maple in Autumn, Fall 1914. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Soft Maple in Autumn, Fall 1914. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound Tamaracks, Fall 1914. Private collection

Tamaracks, Fall 1914. Private collection Approaching Snowstorm, Fall 1915. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Approaching Snowstorm, Fall 1915. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Algonquin Park, Fall 1915. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound

Algonquin Park, Fall 1915. Tom Thomson Art Gallery, Owen Sound Forest, October, Fall 1915. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Forest, October, Fall 1915. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Creative peak (1916–17)

In 1916, Thomson left for Algonquin Park earlier than any previous year, evidenced by the large number of snow studies he produced at this time.[95] He produced many sketches which varied in composition, though they all had vivid colour and were applied thickly.[96] Over the following winter, encouragement from Harris, MacDonald and MacCallum saw Thomson move into the most productive portion of his career,[97] writing in a letter that he "got quite a lot done."[98] It was during this time that he produced many of what became his most famous works, including The Jack Pine and The West Wind.[99]

In the last two years of his life especially, Thomson was particularly skilled in observing atmospheric phenomena, such as temperature, humidity, wind and light.[100] Work from this period—such as The Rapids—demonstrate his adeptness at controlling colour and are painted with a particular "crispness and freshness."[101][102] Other paintings—such as Path Behind Mowat Lodge and Tea Lake Dam—illustrate his bold and expressive brushstrokes.[103] The scale of Thomson's later canvases foreshadow the Algoma canvases the members of the Group of Seven painted after the war.[104] Art historians David Silcox and Harold Town have described this period of Thomson's art as moving in the direction of abstraction.[105][106][note 3]

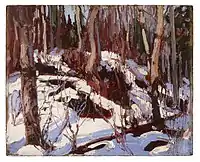

Winter Thaw in the Woods, Fall 1916. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Winter Thaw in the Woods, Fall 1916. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Autumn, Three Trout, Fall 1916. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Autumn, Three Trout, Fall 1916. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Spring Flood, Spring 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

Spring Flood, Spring 1917. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg The Rapids, Spring 1917. Private collection

The Rapids, Spring 1917. Private collection Northern Lights, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Northern Lights, Spring 1917. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Approaching abstraction

Thomson was prolific in the number of sketches he produced—over four hundred across his entire career—providing an opportunity to observe the trends and progression of his style. Starting as a landscape painter, he drew away from typical landscape convention and began to experiment with more excited brushstrokes, clashing paint and more vibrant colours.[108] For artist and Thomson biographer Harold Town, the brevity of Thomson's career hinted at an artistic evolution never fully realized. He cites the 1916 oil painting Unfinished Sketch as "the first completely abstract work in Canadian art," a painting that, whether or not it was intended as a purely non-objective work, presages the innovations of abstract expressionism.[109] Town describes the contents of the painting as being a sky that expresses the frustration Thompson must have experienced in adding paint to the small areas between trees, rocks and thickets.[106] He similarly describes Late Autumn as being another "impatient study" that led to abstract experiment. Of particular importance are the areas between the branches, which are "brusquely smacked into place," as well as a similar foreground to that of Unfinished Sketch.[106]

David Silcox has pointed to Cranberry Marsh as indicating Thomson's move towards abstraction.[110] He has also viewed After the Storm, likely one of Thomson's last paintings, as an indication that Thomson was already responding to the changes happening in Western art, even if he didn't exactly know where it would lead.[111] Examining the painting more closely, the landscape itself dissolves into bare strokes and pure abstraction.[112]

Art historian Joan Murray has expressed reluctance to describe Thomson's sketches as "abstract," given that some of them may have likely been intended as "colour notes for use in the studio," and because some of the sketches were unfinished.[113]

Late Autumn, Fall 1915. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

Late Autumn, Fall 1915. McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg Sketch for Autumn's Garland, Fall 1915. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

Sketch for Autumn's Garland, Fall 1915. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto Cranberry Marsh, Summer 1916. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Cranberry Marsh, Summer 1916. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Algonquin Hillside, Snow, Fall 1916. Private collection

Algonquin Hillside, Snow, Fall 1916. Private collection After the Storm, Summer 1917. Private collection

After the Storm, Summer 1917. Private collection

References

Footnotes

- For more regarding Thomson's photographs, refer to

- Sources disagree on the approximate time of Thomson being hired. Grip supervisor Albert H. Robson wrote in 1932 that he was hired in 1907,[38] but by 1937 Robson was instead writing that he was hired in 1908.[39] Robert Stacey has suggested December 1908.[32] David Silcox has suggested the beginning of 1909.[40] Art historian Joan Murray has suggested December 1908 or January 1909.[41] In curator Charles Hill's investigation, he noted that Thomson is listed in the Toronto City Directory for 1906–09 as working with Legg Bros. Photo Engravers, in 1910 merely as an artist living at 99 Gerrard E., and in 1911 as being at Grip Ltd. Hill supposes that this means Thomson likely began at Grip in late 1909, after the information for the 1910 directory was collected.[42]

- For more regarding Thomson's later abstract tendencies, refer to:

- The painting is on the reverse of Algonquin Hillside, Snow.

Citations

- Silcox (2015), p. 60.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 181.

- Silcox (2015), pp. 59–60.

- Silcox (2006), p. 127.

- Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 181–85.

- Brown (1998), pp. 151, 158.

- Dejardin (2011).

- Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 181–82.

- Murray (1999), p. 110.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 182.

- Murray (2006), p. 92.

- Davies (c. 1930).

- Hill (2002), p. 123.

- Murray (1999), p. 25.

- Hill (2002), p. 125.

- Hill (2002), p. 132.

- Thomson (1917a).

- Hill (2002), pp. 141–42.

- Murray (1994), p. 7.

- Murray (1998), p. 85.

- Murray (1999), p. 116.

- Corbeil et al. (2000).

- Webster-Cook & Ruggles (2002), p. 145.

- Webster-Cook & Ruggles (2002), pp. 145–46.

- Reid (1971).

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 215.

- Silcox (2015), p. 63.

- Thomson (1912).

- Murray (2002a), p. 297.

- Silcox (2015), p. 15.

- Hill (2002), p. 113.

- Stacey (2002), p. 50.

- Silcox (2015), p. 7.

- Stacey (2002), p. 51.

- Stacey (2002), pp. 47–63.

- Silcox (2015), p. 68.

- Thomson (1946).

- Robson (1932), p. 138.

- Robson (1937), p. 5.

- Silcox (2015), p. 9.

- Murray (2002b), p. 310.

- Hill (2002), p. 113 n. 16.

- King (2010), p. 14.

- Rossell (c. 1951), p. 3.

- Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 94, 210.

- Reid (2002), pp. 65–83.

- Stacey (2002), p. 59–60.

- Silcox (2015), p. 68, 71.

- Silcox (2015), p. 47, 71.

- Stacey (2002), p. 60.

- McKay (2011), p. 185.

- Silcox (2015), p. 71.

- Stacey (2002), p. 58.

- Rossell (c. 1951), p. 1.

- Hill (2002), p. 117.

- Hill (2002), p. 118.

- Mortimer-Lamb (1919).

- Lismer (1919).

- Jackson (1924).

- Jackson (1933).

- Hill (2002), p. 115.

- Lismer (c. 1942).

- Silcox (2015), p. 10.

- Silcox (2006), p. 23.

-

- Hunter (2002), p. 25

- Silcox (2006), p. 20

- Silcox (2015), p. 10

- Stacey (2002), p. 57

- Hunter (2002), pp. 25–26.

- Jackson (1931).

- Hill (2002), p. 119.

- Northway (1970), p. 6.

- Addison (1974), p. 75.

- Davies (1935), pp. 35–36.

- Hill (2002), p. 120.

- Robson (1937), p. 6.

- Wadland (2002), p. 95.

- Klages (2016), p. 23.

- Stacey (2002), p. 57–58.

- MacCallum (1918), p. 375.

- Silcox (2006), p. 212.

- Harris (1964).

- Silcox (2006), p. 21.

- Silcox (2015), p. 11.

- MacCallum (1918), p. 376.

- Thomson (1914).

- Silcox (2015), p. 11.

- Silcox (2015), p. 12.

- Davies (1935), pp. 74–75.

- Jackson (1958), p. 31.

- Jackson (1917).

- Hill (2002), p. 127.

- Murray (1999), p. 34.

- Hill (2002), p. 133.

- Murray (1999), p. 70.

- Jackson (1919).

- Hill (2002), p. 135.

- Hill (2002), p. 137.

- Silcox (2015), p. 16.

- Silcox (2006), p. 20.

- Thomson (1917b).

- Silcox (2015), p. 17.

- Silcox (2018), p. 181.

- Hill (2002), p. 141.

- Silcox (2015), p. 17.

- Silcox (2015), pp. 17–18.

- Hill (2002), p. 139.

- Silcox (2015), pp. 17–18, 44, 52, 57, 62, 68, 73.

- Silcox & Town (2017), p. 148.

- Silcox (2015), p. 51.

- Silcox (2015), p. 43.

- Silcox & Town (2017), pp. 148–49.

- Silcox (2015), p. 43–44, 68.

- Silcox (2015), p. 51–52.

- Silcox (2015), p. 52.

- Murray (2015), "From the Studio Building to Algonquin Park and Home Again".

Sources

Primary sources

- Davies, Blodwen. "Tom Thomson's Sketchbox" (c. 1930). Blodwen Davies collection, Series: 11, ID: MG30-D38. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- ——— (1935). A Study of Tom Thomson: The Story of a Man Who Looked for Beauty and for Truth in the Wilderness. Toronto: Discuss Press.

- Harris, Lawren S. (1964). The Story of the Group of Seven. Toronto: Rous and Mann Press.

- Jackson, A. Y. (4 August 1917). "Tom Thomson". Letter to Mrs. Henry Jackson.

- ——— (1919). Foreword. Catalogue of an Exhibition of Paintings by the Late Tom Thomson, March 1 to March 21, 1919. By Arts Club of Montreal.

- ———. "A. Y. Jackson to Norah Thomson" (May 21, 1924) [Letter]. Norah De Pencier, Series: 1, ID: MG30-D322. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- ——— (5 May 1931). "Algonquin Park". Letter to Blodwen Davies.

- ———. "A. Y. Jackson to Marius Barbeau" (March 31, 1933) [Letter]. Marius Barbeau Collection, Box: 19. Ottawa: Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- ——— (1958). A Painter's Country. Toronto: Clarke Irwin.

- Lismer, Arthur. "A. Lismer to J. E. H. MacDonald" (March 21, 1919) [Letter]. Arthur Lismer, Box: 11, ID: MG30-D111. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- ———. "Tom Thomson" (c. 1942). Arthur Lismer, Fonds: Arthur Lismer, Box: 2, ID: MG30-D184. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- MacCallum, James (31 March 1918). "Tom Thomson: Painter of the North". Canadian Magazine. pp. 375–85.

- Robson, Albert H. (1932). Canadian Landscape Painters. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- ——— (1937). Tom Thomson: Painter of Our North Country, 1877-1917. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- Rossell, Leonard. "Reminiscences of Grip, Members of the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson" (c. 1951). Tom Thomson Collection, File: T485.R82, ID: MG30-D284. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

- Thomson, George. "George Thomson to J. M. MacCallum" (July 19, 1917a) [Letter]. Dr. James M. MacCallum Papers, Series: George Thomson correspondence, Box: 1, File: 6, ID: MG30-D38. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada Archives.

- Thomson, Henry (19 October 1946). "Letter to McCurry with a typed copy of draft letter from Ralph Thomson to Blodwen Davies". Letter to H. O. McCurry.

- Thomson, Tom (17 October 1912). "Letter to McRuer". Letter to Dr. M. J. (John) McRuer.

- ———. "Letter to Dr. James MacCallum" (October 6, 1914) [Letter]. Dr. James M. MacCallum Papers, Series: Tom Thomson correspondence, Box: 1, File: 5. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada Archives.

- ———. "Letter to T. J. Harkness" (April 16, 1917b) [Letter]. Tom Thomson correspondence 1912–17, Fonds: Tom Thomson, Series: 1, ID: MG30-D284. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada.

Secondary sources

- Addison, Ottelyn; Harwood, Elizabeth (1969). Tom Thomson: The Algonquin Years. Toronto: Ryerson Press.

- ——— (1974). Early Days in Algonquin Park. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 978-0-07077-786-6.

- Brown, W. Douglas (1998). "The Arts and Crafts Architecture of Eden Smith". In Latham, David (ed.). Scarlet Hunters: Pre-Raphaelitism in Canada. Toronto: Archives of Canadian Art. ISBN 978-1-89423-400-9.

- Corbeil, Marie-Claude; Moffatt, Elizabeth A.; Sirois, P. Jane; Legate, Kris M. (2000). "The Materials and Techniques of Tom Thomson". Journal of the Canadian Association for Conservation. 25: 3–10.

- Dejardin, Ian A. C. (2011). Painting Canada: Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven. London: Dulwich Picture Gallery. ISBN 978-0-85667-686-4.

- Forsey, William C. (1975). The Ontario Community Collects: A Survey of Canadian Painting from 1766 to the Present. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario.

- Hill, Charles (2002). "Tom Thomson, Painter". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 111–143. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Hunter, Andrew (2002). "Mapping Tom". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 19–46. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- King, Ross (2010). Defiant Spirits: The Modernist Revolution of the Group of Seven. Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55365-807-8.

- Klages, Gregory (2016). The Many Deaths of Tom Thomson: Separating Fact from Fiction. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-45973-196-7.

- McKay, Marylin J. (2011). Picturing the Land: Narrating Territories in Canadian Landscape Art, 1500-1950. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-77353-817-7.

- Mortimer-Lamb, Harold (29 March 1919). "Letter to the editor, with attached draft article". Studio Magazine.

- Murray, Joan (1994). Tom Thomson: The Last Spring. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55002-218-6.

- ——— (1998). Tom Thomson: Design for A Canadian Hero. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-55002-315-2.

- ——— (1999). Tom Thomson: Trees. Toronto: McArthur & Co. ISBN 978-1-55278-092-3.

- ——— (2002a). "Tom Thomson's Letters". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 297–306. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- ——— (2002b). "Chronology". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 307–317. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- ——— (2006). Rocks: Franklin Carmichael, Arthur Lismer, and the Group of Seven. Toronto: McArthur & Co. pp. 92–7. ISBN 978-1-55278-616-1.

- ——— (2015). "Thomson-Algonquin / Algonquin-Thomson". tomthomsoncatalogue.org. Tom Thomson Catalogue. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Northway, Mary L. (1970). Nominigan: The Early Years. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Reid, Dennis (1971). "Photographs by Tom Thomson (1970)". National Gallery of Canada Bulletin/Galerie Nationale du Canada Bulletin. 16: 2–36.

- ——— (2002). "Tom Thomson and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Toronto". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 65–83. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Silcox, David P. (2006). The Group of Seven and Tom Thomson. Richmond Hill: Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55407-154-8.

- ——— (2015). Tom Thomson: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute. ISBN 978-1-48710-075-9.

- ———; Town, Harold (2017). The Silence and the Storm (Revised, Expanded ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 978-1-44344-234-3.

- ——— (2018). "A Radical Shift at Six Mile Lake". In Milroy, Sarah; Dejardin, Ian A. C. (eds.). David Milne: Modern Painting. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 179–81. ISBN 978-1-78130-061-9.

- Stacey, Robert (2002). "Tom Thomson as Applied Artist". In Reid, Dennis; Hill, Charles C. (eds.). Tom Thomson. Toronto/Ottawa: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 47–63. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Wadland, John (2002). "Tom Thomson's Places". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 85–109. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.

- Webster-Cook, Sandra; Ruggles, Anne (2002). "Technical Studies on Thomson's Materials and Working Methods". In Reid, Dennis (ed.). Tom Thomson. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario/National Gallery of Canada. pp. 145–51. ISBN 978-1-55365-493-3.