Aspergillus nidulans

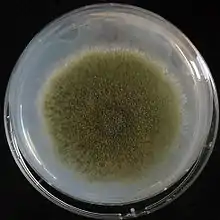

Aspergillus nidulans (also called Emericella nidulans when referring to its sexual form, or teleomorph) is one of many species of filamentous fungi in the phylum Ascomycota. It has been an important research organism for studying eukaryotic cell biology[1] for over 50 years,[2] being used to study a wide range of subjects including recombination, DNA repair, mutation, cell cycle control, tubulin, chromatin, nucleokinesis, pathogenesis, metabolism,[3] and experimental evolution.[4] It is one of the few species in its genus able to form sexual spores through meiosis, allowing crossing of strains in the laboratory. A. nidulans is a homothallic fungus, meaning it is able to self-fertilize and form fruiting bodies in the absence of a mating partner. It has septate hyphae with a woolly colony texture and white mycelia. The green colour of wild-type colonies is due to pigmentation of the spores, while mutations in the pigmentation pathway can produce other spore colours.

| Aspergillus nidulans | |

|---|---|

| |

| A. nidulans with wild-type green spores, grown under laboratory conditions. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Trichocomaceae |

| Genus: | Aspergillus |

| Species: | A. nidulans |

| Binomial name | |

| Aspergillus nidulans G Winter 1884 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Emericella nidulans | |

Genome

The A. nidulans genome was sequenced in a collaboration between Monsanto and the Broad Institute.[5] A sequence with 13-fold coverage was publicly released in March 2003;[5] analysis of the annotated genome was published in Nature in December 2005.[6] It is 30 million base pairs in size and is predicted to contain around 9,500 protein-coding genes on eight chromosomes.

Recently, several caspase-like proteases were isolated from A. nidulans samples under which programmed cell death had been induced. Findings such as these play a key role in determining the evolutionary conservation of the mitochondrion within the eukaryotic cell, and its role as an ancient proteobacterium capable of inducing cell death.

Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction occurs in two fundamentally different ways. This is by outcrossing (heterothallic sex), in which two distinct individuals contribute nuclei, or by homothallic sex or self-fertilization (selfing) in which both nuclei are derived from the same individual. Selfing in A. nidulans involves activation of the same mating pathways characteristic of sex in outcrossing species, i.e. self-fertilization does not bypass required pathways for outcrossing sex but instead requires activation of these pathways within a single individual.[7] Fusion of haploid nuclei occurs within reproductive structures termed cleistothecia, in which the diploid zygote undergoes meiotic divisions to yield haploid ascospores.

Use in pharmaceutical research

Anidulafungin[8] is a semisynthetic lipopeptide antifungal drug of echinocandin B subclass, derived from a fermentation product of A. nidulans var. echinulatus strain A 32204, was discovered in Germany in 1974;[9] echinocandins destabilize the fungal cell wall by inhibiting the synthesis of an integral component called glucan, via the noncompetitive inhibition of the enzyme 1,3-β glucan synthase.[10][11]

References

- Osmani SA, Mirabito PM (2004). "The early impact of genetics on our understanding of cell cycle regulation in Aspergillus nidulans". Fungal Genet Biol. 41 (4): 401–10. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2003.11.009. PMID 14998523.

- Martinelli, S. D.; J. R. Kinghorn (1994). Aspergillus: 50 years on. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-81762-4.

- Nierman WC, May G, Kim HS, Anderson MJ, Chen D, Denning DW (2005). "What the Aspergillus genomes have told us". Med Mycol. 43. Suppl 1 (s1): S3–5. doi:10.1080/13693780400029049. PMID 16110785.

- Schoustra SE, Slakhorst, M, Debets, AJM, Hoekstra, RF (2005). "Comparing artificial and natural selection in rate of adaptation to genetic stress in Aspergillus nidulans". J Evol Biol. 18 (4): 771–778. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.535.8579. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.00934.x. PMID 16033548.

- "Aspergillus nidulans Project Information". Broad Institute. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- Galagan JE; et al. (2005). "Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae". Nature. 438 (7071): 1105–15. doi:10.1038/nature04341. PMID 16372000.

- Paoletti M, Seymour FA, Alcocer MJ, Kaur N, Calvo AM, Archer DB, Dyer PS (August 2007). "Mating type and the genetic basis of self-fertility in the model fungus Aspergillus nidulans". Curr. Biol. 17 (16): 1384–9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.012. PMID 17669651.

- "Anidulafungin EMA Europa" (PDF).

- Nyfeler R, Keller-Schierlein W (1974). "Metabolites of microorganisms. 143. Echinocandin B, a novel polypeptide-antibiotic from Aspergillus nidulans var. echinulatus: isolation and structural components". Helv Chim Acta. 57 (8): 2459–2477. doi:10.1002/hlca.19740570818. PMID 4613708.

- Morris MI, Villmann M (September 2006). "Echinocandins in the management of invasive fungal infections, part 1". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 63 (18): 1693–703. doi:10.2146/ajhp050464.p1. PMID 16960253.

- Morris MI, Villmann M (October 2006). "Echinocandins in the management of invasive fungal infections, Part 2". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 63 (19): 1813–20. doi:10.2146/ajhp050464.p2. PMID 16990627.