Astigmatism (optical systems)

An optical system with astigmatism is one where rays that propagate in two perpendicular planes have different foci. If an optical system with astigmatism is used to form an image of a cross, the vertical and horizontal lines will be in sharp focus at two different distances. The term comes from the Greek α- (a-) meaning "without" and στίγμα (stigma), "a mark, spot, puncture".[1]

| Optical aberration |

|---|

|

Forms of astigmatism

There are two distinct forms of astigmatism. The first is a third-order aberration, which occurs for objects (or parts of objects) away from the optical axis. This form of aberration occurs even when the optical system is perfectly symmetrical. This is often referred to as a "monochromatic aberration", because it occurs even for light of a single wavelength. This terminology may be misleading, however, as the amount of aberration can vary strongly with wavelength in an optical system.

The second form of astigmatism occurs when the optical system is not symmetric about the optical axis. This may be by design (as in the case of a cylindrical lens), or due to manufacturing error in the surfaces of the components or misalignment of the components. In this case, astigmatism is observed even for rays from on-axis object points. This form of astigmatism is extremely important in vision science and eye care, since the human eye often exhibits this aberration due to imperfections in the shape of the cornea or the lens.

.png.webp)

Third-order astigmatism

In the analysis of this form of astigmatism, it is most common to consider rays from a given point on the object, which propagate in two particular planes. The first plane is the tangential plane. This is the plane which includes both the object point under consideration and the axis of symmetry. Rays that propagate in this plane are called tangential rays. Planes that include the optical axis are meridional planes. It is common to simplify problems in radially-symmetric optical systems by choosing object points in the vertical ("y") plane only. This plane is then sometimes referred to as the meridional plane.

The second plane used in the analysis is the sagittal plane. This is defined as the plane, orthogonal to the tangential plane, which contains the object point being considered and intersects the optical axis at the entrance pupil of the optical system. This plane contains the chief ray, but does not contain the optic axis. It is therefore a skew plane, in other words not a meridional plane. Rays propagating in this plane are called sagittal rays.

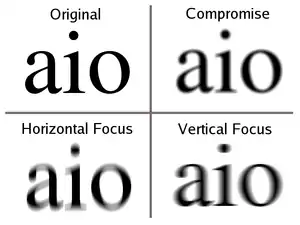

In third-order astigmatism, the sagittal and transverse rays form foci at different distances along the optic axis. These foci are called the sagittal focus and the transverse focus, respectively. In the presence of astigmatism, an off-axis point on the object is not sharply imaged by the optical system. Instead, sharp lines are formed at the sagittal and transverse foci. The image at the transverse focus is a short line, oriented in the direction of the sagittal plane; images of circles centered on the optic axis, or lines tangential to such circles, will be sharp in this plane. The image at the sagittal focus is a short line, oriented in the tangential direction; images of spokes radiating from the center are sharp at this focus. In between these two foci, a round but "blurry" image is formed. This is called the medial focus or circle of least confusion. This plane often represents the best compromise image location in a system with astigmatism.

The amount of aberration due to astigmatism is proportional to the square of the angle between the rays from the object and the optical axis of the system. With care, an optical system can be designed to reduce or eliminate astigmatism. Such systems are called anastigmats.

Astigmatism in systems that are not rotationally symmetric

If an optical system is not axisymmetric, either due to an error in the shape of the optical surfaces or due to misalignment of the components, astigmatism can occur even for on-axis object points. This effect is often used deliberately in complex optical systems, especially certain types of telescope. Some telescopes deliberately use non-spherical optics to overcome this phenomenon.[3]

In the analysis of these systems, it is common to consider tangential rays (as defined above), and rays in a meridional plane (a plane containing the optic axis) perpendicular to the tangential plane. This plane is called either the sagittal meridional plane or, confusingly, just the sagittal plane.

Ophthalmic astigmatism

In optometry and ophthalmology, the vertical and horizontal planes are identified as tangential and sagittal meridians, respectively. Ophthalmic astigmatism is a refraction error of the eye in which there is a difference in degree of refraction in different meridians.[4] It is typically characterized by an aspherical, non-figure of revolution cornea in which the corneal profile slope and refractive power in one meridian is less than that of the perpendicular axis.

Astigmatism causes difficulties in seeing fine detail. Astigmatism can be often corrected by glasses with a lens that has different radii of curvature in different planes (a cylindrical lens), contact lenses, or refractive surgery.[5]

Astigmatism is quite common. Studies have shown that about one in three people suffers from it.[6][7][8] The prevalence of astigmatism increases with age.[9] Although a person may not notice mild astigmatism, higher amounts of astigmatism may cause blurry vision, squinting, asthenopia, fatigue, or headaches.[10][11][12]

There are a number of tests that are used by ophthalmologists and optometrists during eye examinations to determine the presence of astigmatism and to quantify the amount and axis of the astigmatism.[13] A Snellen chart or other eye chart may initially reveal reduced visual acuity. A keratometer may be used to measure the curvature of the steepest and flattest meridians in the cornea's front surface.[14] Corneal topography may also be used to obtain a more accurate representation of the cornea's shape.[15] An autorefractor or retinoscopy may provide an objective estimate of the eye's refractive error and the use of Jackson cross cylinders in a phoropter may be used to subjectively refine those measurements.[16][17][18] An alternative technique with the phoropter requires the use of a "clock dial" or "sunburst" chart to determine the astigmatic axis and power.[19][20]

Astigmatism may be corrected with eyeglasses, contact lenses, or refractive surgery.[21][22][23] Various considerations involving ocular health, refractive status, and lifestyle frequently determine whether one option may be better than another. In those with keratoconus, toric contact lenses often enable patients to achieve better visual acuities than eyeglasses. If the astigmatism is caused by a problem such as deformation of the eyeball due to a chalazion, treating the underlying cause will resolve the astigmatism.

Misaligned or malformed lenses and mirrors

Grinding and polishing of precision optical parts, either by hand or machine, typically employs significant downward pressure, which in turn creates significant frictional side pressures during polishing strokes that can combine to locally flex and distort the parts. These distortions generally do not possess figure-of-revolution symmetry and are thus astigmatic, and slowly become permanently polished into the surface if the problems causing the distortion are not corrected. Astigmatic, distorted surfaces potentially introduce serious degradations in optical system performance.

Surface distortion due to grinding or polishing increases with the aspect ratio of the part (diameter to thickness ratio). To a first order, glass strength increases as the cube of the thickness. Thick lenses at 4:1 to 6:1 aspect ratios will flex much less than high aspect ratio parts, such as optical windows, which can have aspect ratios of 15:1 or higher. The combination of surface or wavefront error precision requirements and part aspect ratio drives the degree of back support uniformity required, especially during the higher down pressures and side forces during polishing. Optical working typically involves a degree of randomness that helps greatly in preserving figure-of-revolution surfaces, provided the part is not flexing during the grind/polish process.

Deliberate astigmatism in optical systems

Compact disc players use an astigmatic lens for focusing. When one axis is more in focus than the other, dot-like features on the disc project to oval shapes. The orientation of the oval indicates which axis is more in focus, and thus which direction the lens needs to move. A square arrangement of only four sensors can observe this bias and use it to bring the read lens to best focus, without being fooled by oblong pits or other features on the disc surface.

In 3D PALM/STORM, a type of optical super-resolution microscopy, a cylindrical lens can be introduced into the imaging system to create astigmatism, which allows measurement of the Z position of a diffraction-limited light source.[24]

Laser line levels use a cylindrical lens to spread a laser beam from a point into a line.

See also

- Anastigmat (lens type)

- Stigmatism

References

- Harper, Douglas (2001). "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- Frederic Eugene Wright (1911). The Methods of Petrographic-microscopic Research, Their Relative Accuracy and Range of Application. Carnegie institution of Washington.

- Sacek, Vladimir (July 14, 2006). "Telescope astigmatism". Amateur Telescope Optics. Archived from the original on 19 September 2008. Retrieved Oct 16, 2008.

- "Facts About Astigmatism | National Eye Institute". nei.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "Astigmatism Laser Eye Surgery". The Irish Times.

- Kleinstein RN, Jones LA, Hullett S, Kwon S, et al. (2003). "Refractive Error and Ethnicity in Children". Arch. Ophthalmol. 121 (8): 1141–7. doi:10.1001/archopht.121.8.1141. PMID 12912692.

- Garcia CA, Oréfice F, Nobre GF, Souza Dde B, Rocha ML, Vianna RN (2005). "[Prevalence of refractive errors in students in Northeastern Brazil.]". Arq Bras Oftalmol (in Portuguese). 68 (3): 321–5. doi:10.1590/S0004-27492005000300009. PMID 16059562.

- Bourne RR, Dineen BP, Ali SM, Noorul Huq DM, Johnson GJ (June 2004). "Prevalence of refractive error in Bangladeshi adults: results of the National Blindness and Low Vision Survey of Bangladesh". Ophthalmology. 111 (6): 1150–60. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.046. PMID 15177965.

- Asano K, Nomura H, Iwano M, et al. (2005). "Relationship between astigmatism and aging in middle-aged and elderly Japanese". Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 49 (2): 127–33. doi:10.1007/s10384-004-0152-1. PMID 15838729.

- Eyetopics.com

- Medicinenet.com

- Hipusa.com Archived May 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Hipusa.com Archived April 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Stlukeseye.com Archived March 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Emedicine.com Archived February 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Graff T (June 1962). "[Control of the determination of astigmatism with the Jackson cross cylinder.]". Klin Monatsblätter Augenheilkd Augenarztl Fortbild (in German). 140: 702–8. PMID 13900989.

- Del Priore LV, Guyton DL (November 1986). "The Jackson cross cylinder. A reappraisal". Ophthalmology. 93 (11): 1461–5. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33545-0. PMID 3808608.

- Brookman KE (May 1993). "The Jackson crossed cylinder: historical perspective". J Am Optom Assoc. 64 (5): 329–31. PMID 8320415.

- Quantumoptical.com

- Nova.edu

- "Contact Lenses for Vision Correction". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2018-09-01. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "Eyeglasses for Vision Correction". American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2015-12-12. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- "LASIK eye surgery". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Huang, Bo (Feb 8, 2008). "Three-dimensional Super-resolution Imaging by Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy". Science. 319 (5864): 810–813. Bibcode:2008Sci...319..810H. doi:10.1126/science.1153529. PMC 2633023. PMID 18174397.

External links

- Astigmatism Articles

- Paul van Walree's Astigmatism and field curvature