August Wesley

August Anselm Wesley (born Wesslin); (3 August 1887; last rumoured to be alive 1942) was a Finnish journalist, trade unionist and revolutionary who was the chief of the Red Guards general staff in the 1918 Finnish Civil War. He later served as a lieutenant in the British organized Murmansk Legion and the Estonian Army.

August Wesley | |

|---|---|

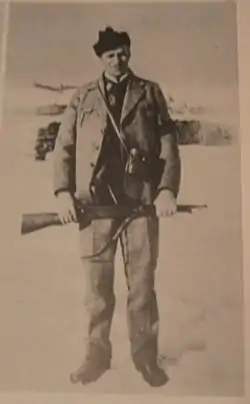

August Wesley in the Finnish Civil War | |

| Native name | August Anselm Wesslin |

| Born | 3 August 1887 Tampere, Grand Duchy of Finland |

| Died | unknown Leningrad, Soviet Union |

| Allegiance | Red Finland Great Britain Estonia |

| Years of service | 1917–1920 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | |

Life

Early years and the Finnish Civil War

August Anselm Wesslin was born in the industrial town of Tampere and emigrated to the United States in 1904 at the age of seventeen.[1] He was an active member of the Socialist Party of America, working as an speaker among the Finnish-American workers. Wesley studied at the Work People's College in Duluth, Minnesota, where he also worked as a teacher in the mid-1910s.[2] He was a journalist in the Finnish-language daily Industrialisti, which was linked to the Industrial Workers of the World.[3] Wesley held the United States citizenship, but as the country joined World War I in 1917, Wesley returned to Finland to avoid the draft.

Wesley moved to Joensuu, in the remote province of North Karelia, the hometown of his spouse, Fanny Käyhkö (1897–1978). Wesley worked as a district party secretary of the Social Democratic Party.[4] During the 1917 general strike, he was the head of the local strike committee and was soon elected commander of the Joensuu Red Guard.[5] As the civil war started in late January 1918, the White Guards took control in Joensuu. Many of the Reds were captured, but Wesley managed to leave the town. He sneaked across the front line to the Red controlled southern Finland and headed to the capital city of Helsinki. He became the commander of the Helsinki Red Guard, and on 16 February, Wesley was named the chief of the Red Guards general staff, the second highest person in the Red Guards hierarchy.[6]

In the Murmansk Legion

After the decisive loss at the Battle of Tampere on 6 April, Wesley was dismissed as Kullervo Manner was given the dictatorial powers.[7] Before the socialist faction fell in late April, Wesley fled to Soviet Russia. He moved to the East Karelia and joined the Murmansk Legion, which was a British organized unit comprising Finnish Red Guard fighters who had fled to Russia. During the Allied North Russia Intervention, Wesley served as an interpreter and an intelligence officer, ranked as a British Navy lieutenant.[8]

Following the German surrender, the status of the Murmansk Legion changed as the Allies and Soviet Russia became enemies. The Finnish commander of the Murmansk Legion, Verner Lehtimäki, stayed loyal to the Bolshevik government, but Wesley, Oskari Tokoi, and Karl Emil Primus-Nyman openly supported the Allies. They urged the Finnish working-class to reject communism and join them in pursuit of a democratic socialist Finland.[9] The exiled Communist Party of Finland declared the three traitors and outlaws.[10]

Afterwards, Wesley revealed Lehtimäki's mutiny plan and his intentions of attacking Finland. As a result, Lehtimäki and some others, like Iivo Ahava, were dismissed from the Legion and joined the Bolshevik side.[8]

Life in Estonia

The Murmansk Legion was disbanded in late 1919. Great Britain and the United States now set a precondition for the recognition of Finland's independence; the government of Finland had to allow the legioneers to return home safely and they could not be punished for their actions. This agreement, however, excluded the Red Guard leaders such as Wesley. He was given permission to move to Britain, but Wesley chose to stay in Estonia. He joined the Estonian Army, where he served as a lieutenant in the War of Independence. After the war, Wesley settled in Tallinn where he first worked for the ministry of social affairs and later as a journalist in the newspaper Vaba Maa.[11][12]

Wesley also translated literature to Estonian and Finnish. One of his translations is the 1937 Estonian version of Laozi's famous work, Tao Te Ching.[13]

During the 1920s and 1930s, Wesley contacted the Finnish government several times asking to return to Finland, but the answer was always the same; the general pardon did not apply to the Red Guard leaders. When the Soviet Union occupied Estonia in June 1940, Wesley went underground. He was last seen in Narva in 1941.[12] According to some newspaper sources, Wesley starved to death in the Siege of Leningrad in 1942.

References

- "August Wesslin". Ellis Island Foundation. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- "Michiganin osavaltiossa Yhdysvalloissa. Työväen Opiston opettajat" (in Finnish). Finnish Labour Museum. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Wasastjerna, Hans R (1957). History of the Finns in Minnesota. Duluth, Minnesota: Minnesota Finnish-American Historical Society. p. 238.

- Partanen, Jukka (2012). Isänmaa ja raja. Suojeluskunnat Pohjois-Karjalassa 1917–1944. Saarijärvi: Pohjois-Karjalan Sotilaspoikien Perinnekilta. p. 32. ISBN 978-952-93143-0-0.

- Palmær, Carsten; Mankinen, Raimo (1973). Finlands röda garden. En bok om klasskriget 1918 (PDF). Gothenburg: Oktoberförlaget. pp. 22–23. ISBN 917-24201-4-6.

- Svechnikov, Mikhail (1925). Vallankumous ja kansalaissota Suomessa. Helsinki: Otava.

- "Sisällissodassa vastakkain kaksi kouluttamatonta armeijaa" (in Finnish). Svinhufvud – Suomen itsenäisyyden tekijät ja vaiheet. 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Kotakallio, Juha (2015). Hänen majesteettinsa agentit: Brittitiedustelu Suomessa 1918–41. Helsinki: Atena. pp. 32–37. ISBN 978-952-30004-7-6.

- Aatsinki, Ulla (2009). Tukkiliikkeestä kommunismiin. Lapin työväenliikkeen radikalisoituminen ennen ja jälkeen 1918. Tampere: University of Tampere. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-951-44757-4-0.

- Lackman, Matti (2015). "Från krigskommunism till upproret i Tallinn. Kommunisternas upprorsverksamhet 1919–1924 och dess inverkan på Finlands säkerhet". Historisk Tidskrift för Finland (in Swedish). 2015 (3): 249. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- "Wesley, August" (in Estonian). Eesti biograafiline andmebaas ISIK. 2004. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- "Memento: August Wesley" (in Estonian). Museum of Occupation. 2005. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- Krull, Hasso (2013). "Tõlkeklassika: Laozi "Daodejing"". Ninniku (in Estonian). 2013 (13). Retrieved 11 April 2017.