Bacillus coagulans

Bacillus coagulans is a lactic acid-forming bacterial species. The organism was first isolated and described as Bacillus coagulans in 1915 by B.W. Hammer at the Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station as a cause of an outbreak of coagulation in evaporated milk packed by an Iowa condensary.[1] Separately isolated in 1935 and described as Lactobacillus sporogenes in the fifth edition of Bergey's Manual, it exhibits characteristics typical of both genera Lactobacillus and Bacillus; its taxonomic position between the families Lactobacillaceae and Bacillaceae was often debated. However, in the seventh edition of Bergey's, it was finally transferred to the genus Bacillus. DNA-based technology was used in distinguishing between the two genera of bacteria which are morphologically similar and possess similar physiological and biochemical characteristics.[2][3]

| Bacillus coagulans | |

|---|---|

| |

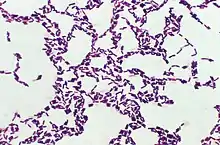

| Gram stain of Bacillus coagulans. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Firmicutes |

| Class: | Bacilli |

| Order: | Bacillales |

| Family: | Bacillaceae |

| Genus: | Bacillus |

| Species: | B. coagulans |

| Binomial name | |

| Bacillus coagulans Hammer, 1915 | |

Bacillus coagulans is a Gram-positive rod (0.9 by 3.0 to 5.0 μm in size), catalase positive, spore-forming, motile, and a facultative anaerobe. It may appear Gram-negative when entering the stationary phase of growth. The optimum temperature for growth is 50 °C (122 °F); range of temperatures tolerated are 30–55 °C (86–131 °F). IMViC tests VP and MR (methyl-red) tests are positive.

Uses

Bacillus coagulans has been added by the EFSA to their Qualified Presumption of Safety list[4] and has been approved for veterinary purposes as GRAS by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Center for Veterinary Medicine, as well as by the European Union, and is listed by AAFCO for use as a direct-fed microbial in livestock production. It is often used in veterinary applications, especially as a probiotic in pigs, cattle, poultry, and shrimp. Many references to use of this bacterium in humans exist, especially in improving the vaginal flora,[5][6][7] improving abdominal pain and bloating in irritable bowel syndrome patients,[8] and increasing immune response to viral challenges.[9] There is evidence from animal research that suggests that Bacillus coagulans is effective in both treating as well as preventing recurrence of clostridium difficile associated diarrhea.[10] One strain of this bacterium has also been assessed for safety as a food ingredient.[11] Spores are activated in the acidic environment of the stomach and begin germinating and proliferating in the intestine. Sporeforming B. coagulans strains are used in some countries as probiotics for patients on antibiotics .[12]

Marketing

Bacillus coagulans is often marketed as Lactobacillus sporogenes or a 'sporeforming lactic acid bacterium' probiotic, but this is an outdated name due to taxonomic changes in 1939. Although B. coagulans does produce L+lactic acid, the bacterium used in these products is not a lactic-acid bacterium, as Bacillus species do not belong to the lactic acid bacteria. By definition, lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) do not form spores. Therefore, using the name Lactobacillus sporogenes is scientifically incorrect.[2]

References

- Hammer, B. W. 1915. Bacteriological studies on the coagulation of evaporated milk. Iowa Agric. Exp. Stn. Res. Bull. 19:119-131

- Bacillus coagulans (Lactobacillus sporogenes) a probiotic ?

- "Official list of bacterial names". Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- The maintenance of the list of QPS microorganisms intentionally added to food or feed - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Biological Hazards

- Sanders, M. E.; Morelli, L.; Tompkins, T. A. (2003). "Sporeformers as Human Probiotics: Bacillus, Sporolactobacillus, and Brevibacillus". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2 (3): 101–110. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00017.x.

- Hong et al., 2005; SCAN

- "LACTOBACILLUS SPOROGENES OR BACILLUS COAGULANS: MISIDENTIFICATION OR MISLABELLING?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-05. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- Hun, L. (2009). "Bacillus coagulans significantly improved abdominal pain and bloating in patients with IBS". Postgraduate Medicine. 121 (2): 119–124. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.03.1984. PMID 19332970.

- Baron, M. (2009). "A patented strain of Bacillus coagulans increased immune response to viral challenge". Postgraduate Medicine. 121 (2): 114–118. doi:10.3810/pgm.2009.03.1971. PMID 19332969.

- Fitzpatrick, LR. (Aug 2013). "Probiotics for the treatment of Clostridium difficile associated disease". World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 4 (3): 47–52. doi:10.4291/wjgp.v4.i3.47. PMC 3740259. PMID 23946887.

- Endres, J. R.; Clewell, A.; Jade, K. A.; Farber, T.; Hauswirth, J.; Schauss, A. G. (2009). "Safety assessment of a proprietary preparation of a novel Probiotic, Bacillus coagulans, as a food ingredient". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 47 (6): 1231–1238. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2009.02.018. PMC 2726964. PMID 19248815.

- Bomko TV, Nosalskaya TN, Kabluchko TV, Lisnyak YV, Martynov AV (2017). "Immunotropic aspect of the Bacillus coagulans probiotic action". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 69 (8): 1033–40. doi:10.1111/jphp.12726. PMID 28397382.

External links

- Hong, H. A.; Duc, L. H.; Cutting, S. M. (2005). "The use of bacterial spore formers as probiotics". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 29: 813–835. Archived from the original on 2009-08-01.

- US National Library of Medicine

- Type strain of Bacillus coagulans at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase