Balantidiasis

Balantidiasis is a protozoan infection caused by infection with Balantidium coli.[1]

| Balantidiasis | |

|---|---|

| |

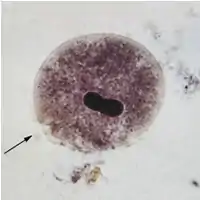

| Balantidium coli as seen in a wet mount of a stool specimen. The organism is surrounded by cilia. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

Symptoms and signs

Usually asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals, but the symptoms of balantidiasis include:

- Intermittent diarrhea

- Constipation

- Vomiting

- Abdominal pain

- Anorexia

- Weight loss

- Headache

- Colitis

- Marked fluid loss

The most common ones are intermittent diarrhea and constipation or inflammation of the colon combined with abdominal cramps and bloody stools.

Transmission

Balantidium is the only ciliated protozoan known to infect humans. Balantidiasis is a zoonotic disease and is acquired by humans via the feco-oral route from the normal host, the pig, where it is asymptomatic. “Contaminated water is the most common mechanism of transmission. Equally dangerous, however, is the ingestion of contaminated food.” [2]

Morphology

Balantidium coli exists in either of two developmental stages: trophozoites and cysts.[3] In the trophozoite form, they can be oblong or spherical, and are typically 30 to 150 µm in length and 25 to 120 µm in width.[4] It is its size at this stage that allows Balantidium coli to be characterized as the largest protozoan parasite of humans.[3] Trophozoites possess both a macronucleus and a micronucleus, and both are usually visible.[3] The macronucleus is large and sausage-shaped while the micronucleus is less prominent.[4] At this stage, the organism is not infective but it can replicate by transverse binary fission.[3]

In its cyst stage, the parasite takes on a smaller, more spherical shape, with a diameter of around 40 to 60 µm.[4] Unlike the trophozoite, whose surface is covered only with cilia, the cyst form has a tough wall made of one or more layers.[3] The cyst form also differs from the trophozoite form because it is non-motile and does not undergo reproduction.[3] Instead, the cyst is the form that the parasite takes when it causes infection.[3]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of balantidiasis can be an intricate process, partly because the related symptoms may or may not be present. However, the diagnosis of balantidiasis can be considered when a patient has diarrhea combined with a probable history of current exposure to pigs (since pigs are the primary reservoir), contact with infected persons, or anal intercourse.[5] In addition, the diagnosis of balantidiasis can be made by microscopic examination of stools in search of trophozoites or cysts,[6] or colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy to obtain a biopsy from the large intestines which may provide evidence for the presence of trophozoites.

Prevention

Preventative measures require effective personal and community hygiene. Some specific safeguards include the following:

- Purification of drinking water.

- Proper handling of food.

- Careful disposal of human feces.

- Monitoring the contacts of balantidiasis patients.

Treatment

Balantidiasis can be treated with tetracycline,[7] carbarsone, metronidazole, or diiodohydroxyquin.

History

The first study to generate balantidiasis in humans was undertaken by Cassagrandi and Barnagallo in 1896.[8] However, this experiment was not successful in creating an infection and it was unclear whether Balantidium coli was the actual parasite used.[8] The first case of balantidiasis in the Philippines, where it is the most common, was reported in 1904.[9][4] Currently, Balantidium coli is distributed worldwide but less than 1% of the human population is infected.[10][4] Pigs are a major reservoir of the parasite, and infection of humans occurs more frequently in areas where pigs comingle with people.[10] This includes places like the Philippines, as previously mentioned, but also includes countries such as Bolivia and Papua New Guinea.[10][11] But pigs are not the only animal where the parasite is found. For example, Balantidium coli also has a high rate of incidence in rats.[12] In a Japanese study that analyzed the fecal samples in 56 mammalian species, Balantidium coli was found to be present not just in all the wild boars tested (with wild boars and pigs being considered the same species), it was also found in five species of non human primate: Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), White-handed gibbon (Hylobates lar), Squirrelmonkey (Saimiri sciurea), Sacred baboon (Comopithecus hamadryas), and Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata).[13] In other studies, Balantidium coli was also found in species from the orders Rodentia and Carnivora.[13]

References

- Schuster FL, Ramirez-Avila L (October 2008). "Current World Status of Balantidium coli". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21 (4): 626–38. doi:10.1128/CMR.00021-08. PMC 2570149. PMID 18854484.

- Dwight D., Bowman (December 9, 2013). Georgi's Parasitology For Veterinarians. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders.: Saunders; 10 edition.

- Ramachandran, Ambili. "Morphology." The Parasite: Balantidium coli The Disease: Balantidiasis. 23 May 2003. Stanford University. 16 May 2009 <http://www.stanford.edu/group/parasites/ParaSites2003/Balantidium/Morphology.htm>.

- Roberts, Larry S., and John Janovy Jr. Gerald D. Schmidt & Larry S. Roberts' Foundations of Parasitology. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009.

- Ferry T, Bouhour D, De Monbrison F, et al. (May 2004). "Severe peritonitis due to Balantidium coli acquired in France". Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 23 (5): 393–5. doi:10.1007/s10096-004-1126-4. PMID 15112068. S2CID 20552666.

- Walzer PD, Judson FN, Murphy KB, Healy GR, English DK, Schultz MG (January 1973). "Balantidiasis outbreak in Truk". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 22 (1): 33–41. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1973.22.33. PMID 4684887.

- "Balantidiasis: Treatment & Medication - eMedicine Infectious Diseases". Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- McCarey AG (March 1952). "Balantidiasis in South Persia". Br Med J. 1 (4759): 629–31. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4759.629. PMC 2023172. PMID 14905008.

- Mason CW (1919). "A Case of Balantidium coli Dysentery". Journal of Parasitology. 5 (3): 137–8. doi:10.2307/3271167. JSTOR 3271167.

- Parasites and Health: Balantidiasis Balantidium coli. Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine DPDx - Balantidiasis. 5 Dec. 2008. CDC Division of Parasitic Diseases. 16 May 2009 >.

- Ramachandran, Ambili. "Epidemiology of Balantidiasis." The Parasite: Balantidium coli The Disease: Balantidiasis. 23 May 2003. Stanford University. 16 May 2009 <http://www.stanford.edu/group/parasites/ParaSites2003/Balantidium/Epidemiology.htm>.

- Prevention, CDC - Centers for Disease Control and. "CDC - Balatidiasis - Biology". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- Nakauchi, Kiyoshi. "The Prevalence of Balantidium coli Infection in Fifty-Six Mammalian Species." Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 61 (1999): 63-65.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |