Battle of Carbisdale

The Battle of Carbisdale (also known as Invercarron) took place close to the village of Culrain, Sutherland, Scotland on 27 April 1650 and was part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It was fought by the Royalist leader James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, against the Scottish Government of the time, dominated by Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll and a grouping of radical Covenanters, known as the Kirk Party. The Covenanters decisively defeated the Royalists. The battlefield has been inventoried and protected by Historic Scotland under the Scottish Historical Environment Policy of 2009.[10] Although Carbisdale is the name of the nearest farm to the site of the battle, Culrain is the nearest village.[2]

| Battle of Carbisdale | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms | |||||||

The Royalists were in the field to the left of the village, and fled up the hill in the top-left of this photo | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

300 men (five troops of cavalry and a group of musketeers)[5] 400 clansmen (from Clan Munro and Clan Ross)[5] |

50 cavalry[5] 1,000 infantry (from Orkney)[5] 500 mercenaries (Swedish, German and Danish)[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Two men wounded and one drowned,[6] "low"[7] |

450+ killed + 200 drowned[8] 400+ captured[9] | ||||||

| Designated | 30 November 2011 | ||||||

| Reference no. | BTL19 | ||||||

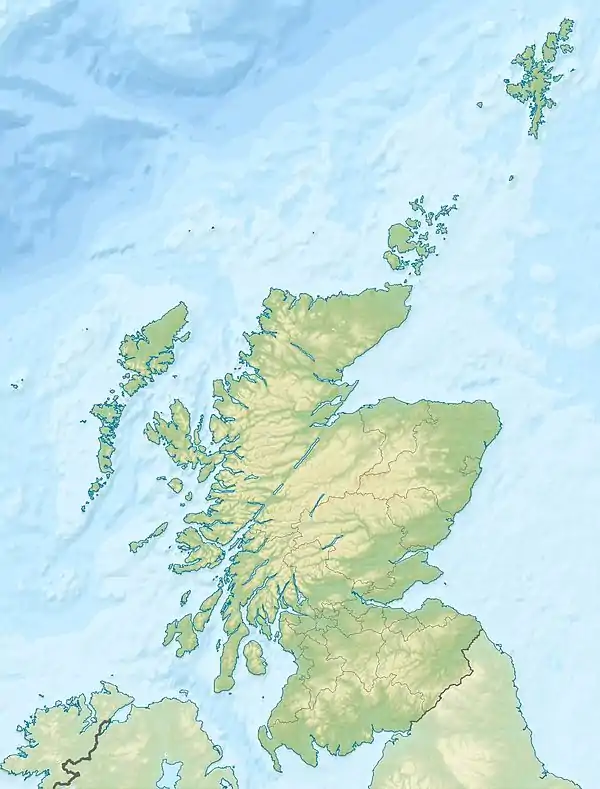

Location within Scotland | |||||||

Charles and Montrose

After the execution of Charles I in January 1649, Scotland entered a period of complex political manoeuvring. His son was immediately proclaimed as Charles II in Edinburgh, though it was soon to be made clear to him that if he were ever to exercise real power he would be obliged to subscribe to a radical Presbyterian agenda. Amongst other things, he would be required to take the Covenants of 1638 and 1643, a move his father had always resisted.[11]

In exile at The Hague, Charles was anxious to take the quickest way back to the throne. He initially favoured calling on the assistance of the Catholic Irish authorities at Kilkenny, until this option was removed by Oliver Cromwell in the summer of 1649. In attacking the Covenanters, Charles hoped to put them in a more accommodating frame of mind. One way of doing this was to take the advice of the ultra-royalist James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, who had led a military campaign against the Covenanters in 1644 and 1645, enjoying some notable successes.[11]

On 20 February 1649 Charles appointed Montrose as Lieutenant-Governor of Scotland and Captain General of all of his forces there. Although he was about to receive a deputation from the government in Edinburgh he was prepared to listen to Montrose's more militant advice, especially as there were already some stirrings against the Covenanters in northern Scotland.[11]

Landing in Orkney

The Committee of Estates had no money to pay troops with. All of the burghs in the south of Scotland had been exasperated by taxes. The former Covenanter general William Baillie had been a member of the Engagers and general John Urry (or Hurry) was now a companion of Montrose. On the opposing side was general David Leslie, 1st Lord Newark who was supported by his lieutenants, Archibald Strachan and James Holborne of Menstrie. Leslie had no more than three thousand foot and fourteen hundred horse who were spread out over the Scottish Highlands. Montrose had hoped to raise as many as 10,000 men in the Highlands alone to support him. However, as it transpired the local clans did not rise up in his support, he had too few foreign troops and there was no sign of any movement in the Scottish Lowlands. By April 1650, Montrose had four to five hundred Danish troops in the Orkneys as well as 1,000 Orcadian men who were far from being a war-like people. Among Montrose's commanders were a number of cavaliers and "soldiers of fortune", including James Crichton, 1st Viscount Frendraught, Sir William Johnston, Colonel Thomas Gray, Harry Graham, John Urry, Hay of Dalgetty, Drummond of Balloch, Ogilvie of Powrie, Menzies of Pitfodels, Douglas the brother of Lord Morton as well as some English Royalists including Major Lisle.[9]

Urry was dispatched with 500 men in advance to find a way of landing on the main land and secured the Ord of Caithness for this purpose with no difficulty. Montrose and the rest of the army followed on around 12 April 1650. They took shelter in the hills where they were safe from the Covenanter horse. Meanwhile, on the opposing side, Leslie held Brahan Castle, the Castle Chanonry of Ross, Eilean Donan Castle and Cromarty Castle. John Gordon, 14th Earl of Sutherland also supported the Covenanters and garrisoned Dunrobin Castle, Skibo Castle and Dornoch Castle. Montrose's movements were rapid, landing in John o' Groats and advancing on Thurso where all of the local gentry, except for the Sinclairs, signed their oath of allegiance. Montrose left Harry Graham with 200 men in Thurso and then marched to Dunbeath Castle which belonged to Sir John Sinclair and took it after a siege of just a few days, leaving a garrison in it. Montrose then joined Urry at the Ord of Caithness with about 800 remaining men, but was denied Sutherland's Dunrobin Castle which was too strong for him to take. Montrose then proceeded inland along Glen Fleet to Lairg and to the foot of Loch Shin. He was hoping for support from the Clan Munro and Clan Ross, but above all from the Clan Mackenzie.[9][12]

Meanwhile, Leslie was heading north to a rendezvous at Brechin and instructed Strachan who commanded the Covenanter troops in Moray to check Montrose's advance. Strachan, with the garrisons of Brahan and Chanonry then came north to Tain where he was joined by more Covenanter troops. He had 220 veteran horse, 36 musketeers as well as a reserve force of 400 Munro and Ross clansmen - who Montrose had hoped would join his force. The Earl of Sutherland was sent north to oppose Harry Graham and in doing so cut off the way of retreat for Montrose in that direction.[9]

Strachan's Ride

On Saturday, 27 April 1650, Strachan marched west from Tain to Wester Fearn, on the southern shore of the Kyle of Sutherland, a few miles south-east of Bonar Bridge. Leslie had only left Brechin on the same day. Montrose had marched down the Strath Oykel to a spot near the head of the Kyle of Sutherland under the side of a steep hill called Craigcaoinichean and was more or less level with Carbisdale. Montrose encamped there for several days waiting for the Mackenzies to arrive. Strachan reached Wester Fearn at about 3pm on 27 April. He knew the position of the enemy and knew that he needed to draw them down from the hill to the flat ground where he could use his cavalry. He therefore concealed most of his horse among the long broom which covered the slopes of Wester Fearn, while the Munros and Rosses went up the River Carron to a place on the heights above Carbisdale where they awaited further orders.[9] Strachan's scout, Andrew Munro, son of John Munro of Lemlair, reported to Strachan that Montrose's horse had been sent out to ascertain his position and Munro advised Strachan to send out a single troop of horse to deceive the enemy into thinking that they were few in number.[13] Strachan accordingly sent a single troop of horse up the valley and Major Lisle's reconnaissance force of 40 horse reported back to Montrose that there was just one troop of horse opposing them. One of Montrose's gentlemen-volunteers, Munro of Achness, assured him of the victory as there was only one troop of horse that opposed them. Montrose then ordered his foot soldiers to advance,[9] but made no special preparations to defend himself,[6] while Strachan was bringing forward the rest of his troops from Wester Fearn.[9]

Strachan then organised his force into four divisions: the first consisted of about 100 horse and which he led in person; the second consisted upwards of 80 and was commanded by General Hacket; the third, also horse, numbered about 40 and was led by Captain Hutcheson; the fourth division included the musketeers, the Munros and Rosses, and was commanded by Colonel John Munro of Lemlair, Ross of Balnagowan and Quarter-Master Shaw.[6]

Carbisdale

Strachan's plan was to advance with his own division to make it look as though his whole strength was just one hundred horse.[6] Strachan's one hundred dragoons then suddenly attacked Montrose's 40 horse who were forced backwards onto Montrose's foot soldiers who had not been deployed for battle and were easily thrown into confusion. Montrose's foot soldiers amounted to no more than 1200, 400 of whom were Danes and Germans, and the rest raw levies from Orkney. They were not accustomed to receiving a cavalry charge unsupported and while the German and Danish mercenaries fell back in some order,[9] discharging a volley into the advancing horse,[6] the Orcadians fell back in disorder. Strachan's reserves, including his musketeers then fell upon the Royalists. Menzies of Pitfoddels was shot dead at Montrose's side. The remnants of his Royalist army tried to make a stand on the hillside on the wooded slopes of Craigcaoinichean. Buchan states that the Munros and Rosses then came down from the hills, convinced at last to take their share in the victory.[9] However, historian C.I Fraser of Reelig states that the Munro clan had no cause to be hesitant about their part in this action and that John Buchan has done less than justice to it.[14]

The Orcadians were cut down or drowned trying to cross the Kyle of Sutherland. Montrose had been wounded several times and his horse was shot from underneath him. He escaped on Crichton of Frendraught's horse, provided to him by Crichton himself.[9] Among the officers killed on Montrose's side were Thomas Ogilvey, Laird of Powrie, Gilbert Menzies, Laird of Pitfoddels, John Douglas, youngest son of William, Earl of Morton, Colonel J. Gordon, Major Lisle, Major Biggar, Major Guthrie, Captain Stirling (another source says he was executed), Capitain Powell, Captain Swan (another account says that he was banished but this could have been another man with the same name), Captain Erskine, Captain Garrie and Lieutenant Home (Holme). There were also about 450 common soldiers killed and another 200 drowned.[8]

According to Buchan, Urry was captured with 58 officers and nearly 400 soldiers.[9] According to the Montrose Memoirs, those taken prisoner were Urry, along with: Crichton, Viscount Frendraught, Colonel Thomas Gray, Lieutenant-Colonel Stewart, Lieutenant-Colonel James Hay, Major Affleck, Captain John Spottiswood, Captain William Ross (banished to France for life), Captain Mortimer, Rittmaster Wallensius (possibly a Dane), Peter Suanes, Captain of Dragoons, Captain Warden (possibly an Englishman), Captain Auchinleck (possibly the same person recorded as Captain Affleck), Captain Lawson, Captain-Lieutenant Gustavus (possibly a Swede), Lieutenant Verkin (a foreigner), Lieutenant Andrew Glen, Lieutenant Rob Touch, Ernestus Buerham (possibly a Dane or Holsteiner), Laurence Van Luitenberge (possibly Dutch), Lieutenant David Drummond (banished to France), Lieutenant John Drummond, Lieutenant James Dun, Lieutenant Alexander Stewart, Cornet Ralph Marlie (Murray), Cornet Henrick Erlach (possibly a Holsteiner), Cornet Daniel Bennicke (possibly a Holsteiner), Ensign Robert Graham, Ensign Adrian Ringwerthe (possibly a Holsteiner), Ensign Hans Boaz (possibly a Holsteiner), 2 Quartermasters, 6 Sergeants, 15 Corporals, 2 Trumpeters, 3 Drummers and 386 common soldiers.[15]

Strachan's force suffered just two men wounded and one trooper drowned.[6] His scout had been John Munro of Lemlair while Montrose's scout had been Robert Munro of Achness and historians have therefore speculated whether Munro of Achness had lured Montrose into a trap by giving him false information.[5] According to the Montrose Memoirs, Munro of Achness and his three sons all escaped death or capture at Carbisdale and do not appear in the Parliamentary records of proceedings against Montrose's followers.[16] However, historian Alexander Mackenzie states that Robert Munro of the Assynt, Inveran and Achness branch of the family, along with his two nephews, Hugh and John, were banished to the New England states of North America by Oliver Cromwell for having fought as Royalists at the Battle of Worcester just one year later in 1651.[17]

Death of Montrose

Montrose was without food or shelter for two or three days.[9] He managed to avoid capture, disguised as a shepherd, until he finally made it to Ardvreck Castle, seat of MacLeod of Assynt. There is a strong tradition that MacLeod had served with Montrose at the siege of Inverness in 1645 and Montrose would have gone to Ardvreck expecting a place of refuge. However, when Montrose arrived MacLeod was away and he was met instead by MacLeod's wife, Christian Munro, daughter of Munro of Lemlair who had fought on the opposite side at Carbisdale. Montrose was confined in the vaulted cellars of the castle along with Major Sinclair, who had been found wandering in the hills.[5] MacLeod was given a £25,000 reward for turning Montrose over to his enemies.[18] He was taken to Edinburgh where he was hanged on 21 May.[5] After execution his body was dismembered, the quarters were publicly displayed in Aberdeen, Glasgow, Perth and Stirling and the head on the Tolbooth in Edinburgh, where it remained for eleven years.[19] After the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, Montrose's remains were given one of the grandest state funerals ever held in Scotland. In 1707, Montrose's great-grandson, also called James Graham, the 4th Marquess, was created the 1st Duke of Montrose.[3]

References

- Lynch, Michael, ed. (2011). Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-19-923482-0.

- "Battle of Carbisdale". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Way, George of Plean; Squire, Romilly of Rubislaw (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. Glasgow: HarperCollins (for the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). p. 149. ISBN 0-00-470547-5.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2008-07-30). Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization. ISBN 9780313359200.

- "The 1st Marquis of Montrose Society - Battle of Carbisdale". montrose-society.org.uk. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1899). "The Munros of Limlair". History of the Munros of Fowlis. Inverness: A. & W, Mackenzie. pp. 488-489.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2008-07-30). Wars of the Age of Louis XIV, 1650-1715: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization. ISBN 9780313359200.

- Wishart, George; Murdoch, Alexander Drimmie; Simpson, Harry Fife Morland (1893). "Appendix I". The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose, 1639-1650. London and New York City: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 493.

- Buchan, John (1913). "The Last Campaign". The Marquis of Montrose. London: T. Nelson Publishers. pp. 233-246.

- "Inventory battlefields". Historic Scotland. Retrieved 2012-04-12.

- Buchan, John (1913). "The Years of Exile". The Marquis of Montrose. London: T. Nelson Publishers. pp. 217-232.

- Wedgwood, C. V (1998). Montrose. Gloucester: Sutton Publishing. pp. 138–140. ISBN 0750917539.

- Wishart, George; Murdoch, Alexander Drimmie; Simpson, Harry Fife Morland (1893). "Deeds of Montrose". The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose, 1639-1650. London and New York City: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 307.

- Fraser, C.I. of Reelig (1954). The Clan Munro. Stirling: Johnston & Bacon. p. 26. ISBN 0-7179-4535-9.

- Wishart, George; Murdoch, Alexander Drimmie; Simpson, Harry Fife Morland (1893). "Appendix I". The Memoirs of James, Marquis of Montrose, 1639-1650. London and New York City: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 493-495.

- Wishart, George; Murdoch, Alexander Drimmie; Simpson, Harry Fife Morland (1893). "Chapter IX". p. 310.

- Mackenzie (1898). pp. 465-466 and 560.

- Keay, John; Keay, Julia (1994). Collins Enclyclopaedia of Scotland. Hammersmith, London: HarperCollins Publisher. p. 136. ISBN 0002550822.

- Cavendish 2000.

Bibliography

- Cavendish, Richard (2000). The Execution of Montrose. 50. History Today.

Further reading

- Cown, E., Montrose-For Covenant and King, 1995.

- Hewison, J. K. The Covenanters, 1913.

- Hutton, R., Charles the Second, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, 1989.

- Napier, M., Memoirs of the Marquis of Montrose, 1852.

- Reid, S., The Campaigns of Montrose, 1990.

- Stevenson, D., Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Scotland, 1644-1651, 1977.