Battle of Forts Clinton and Montgomery

The Battle of Forts Clinton and Montgomery was an American Revolutionary War battle fought in the highlands of the Hudson River valley, not far from West Point, on October 6, 1777. British forces under the command of General Sir Henry Clinton captured Fort Clinton and Fort Montgomery, and then dismantled the first iteration of the Hudson River Chain. The purpose of the attack was to create a diversion to draw American troops from the army of General Horatio Gates, whose army was opposing British General John Burgoyne's attempt to gain control of the Hudson.

| Battle of Forts Clinton and Montgomery | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

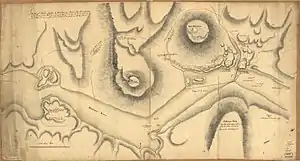

A 1777 military map depicting the battle movements | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 600 men[1] | 2,100 men[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

75 killed and wounded[3] 263 captured[4] |

41 killed 142 wounded[4] | ||||||

The forts were garrisoned by about 600 Continental Army troops under the command of two brothers, General (and Governor of New York) George Clinton, and General James Clinton, while General Israel Putnam led additional troops at nearby Peekskill, New York. (This battle is also sometimes called the "battle of the Clintons" due to the number of participants with that name. The brothers were probably not related to Sir Henry.) Using a series of feints, Henry Clinton fooled Putnam into withdrawing most of his troops to the east, and then he landed over 2,000 troops on the west side of the Hudson to assault the two forts.

After several hours of hiking through the hilly terrain, Clinton divided his troops to stage simultaneous assaults on the two forts. Although the approach to Fort Montgomery was contested by a company armed with a small field piece, they attacked the two forts at nearly the same time and captured them after a relatively short battle. More than half the defenders were killed, wounded, or captured. The British followed up this success with raids as far north as Kingston before being recalled to New York City. The action came too late to be of any assistance to Burgoyne, who surrendered his army on October 17. The only notable consequences of the action were the casualties suffered and the British destruction of the two forts on their departure.

Background

The Hudson River valley was a strategically critical area throughout the American Revolutionary War. Through this area moved supplies, men and materials between the New England states and those further south, something that became even more vitally important when the British largely abandoned New England as an objective of military control later in the war. In June 1777, General John Burgoyne began an attempt to gain control of this key area by moving south from the British province of Quebec. After his early success at Ticonderoga, his campaign become bogged down in logistical difficulties, not reaching Saratoga, New York until mid-September.[5] Burgoyne held expectations that his campaign would be supported by military forces based in New York City under the command of General William Howe, and that the forces would meet at Albany, about 40 miles (64 km) south of Saratoga.[6]

Apparently as result of poor communications with Lord Germain, Britain's Secretary of State for the Colonies and the political official in charge of the conflict, General Howe decided instead to attempt the capture of Philadelphia, and sailed south with much of his army in July, leaving Sir Henry Clinton in command at New York.[7][8] Howe's instructions to General Clinton were primarily to hold New York City, and to only engage in offensive operations that were consistent with that goal. His instructions to Clinton on July 30 included a promise that reinforcements would arrive (but without any promised time), and that Clinton should consider making a move "in favor or General Burgoyne's approaching Albany, with security to Kingsbridge" if the opportunity presented itself.[9] A letter from Howe reached Burgoyne on August 3 informing him of his move to Philadelphia, and of Clinton's instructions.[8] Clinton wrote a letter on September 12 (received by Burgoyne on the 21st, after the Battle of Freeman's Farm) that he would "make a push at [Fort] Montgomery in about ten days" if "you think 2000 men can assist you effectually".[10]

Prelude

British Forces

British forces involved in the battle were:[11]

- British Forces

- (detachment) 17th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons

- 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers)

- 17th Regiment of Foot

- 26th Regiment of Foot

- 52nd Regiment of Foot

- 57th Regiment of Foot

- 63rd Regiment of Foot

- Company, 1st Battalion, 71st Regiment of Foot

- German Forces

- Grenadier Company, 1st Anspach-Beyreuth Regiment

- Regiment von Trumbach (Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel)

- Colonial Forces

- Loyal American Regiment

- Emmerich's Chasseurs

- New York Volunteers

- King's American Regiment

- King's Orange Rangers

American defenses

The highland region of the Hudson River valley (near West Point) was defended by Continental Army troops and state militia under the command of Major General Israel Putnam, who was based at Peekskill. Several miles upriver from Peekskill, just above the Popolopen Gorge where Popolopen Creek enters the Hudson, the Americans had placed a chain across the Hudson to prevent British naval vessels from sailing further upriver. The chain's western end was guarded by Fort Montgomery (named for the late General Richard Montgomery), which also overlooked the gorge to the south. Also on the west side of the river, south of the gorge, they had established Fort Clinton (probably named for General James Clinton).[12][13] Fort Montgomery, which was still undergoing construction, was under the command of General (and Governor of New York) George Clinton, while Fort Clinton was under the command of his older brother James. Their combined forces numbered about 600.[1]

The primary camp at Peekskill, which any British naval movements would need to pass, had roughly 600 men. Of the men at the three sites, about 1,000 were regular troops, while the remainder were short-term New York militia. Putnam's forces had originally been larger, but General Washington had ordered some of Putnam's troops to assist either his (Washington's) defense against Howe or Gates' defense against Burgoyne, and a number of local militia companies had been dismissed when Howe's movements became known.[14] Putnam received word of the arrival of transports in New York on September 29, and wrote Governor Clinton for assistance, who immediately came south from Kingston to take charge of the forts.[15]

British movements

In mid-September (around the time he wrote the letter to Burgoyne), Sir Henry Clinton had around 7,000 men, including around 3,000 poorly trained Loyalists, to defend New York City.[16] His letter to Burgoyne had been predicated on the expectation that the expected reinforcements would arrive in time for him to make a move up the Hudson within ten days.[17] On September 29, he received a letter from Burgoyne (written after Freeman's Farm) in response to his that was a direct plea for action.[15]

Burgoyne to Sir Henry Clinton, September 23, 1777[15]

By the end of September, 1,700 additional troops were landed from the fleet arriving at New York. On October 3, Sir Henry started up the Hudson River with 3,000 men in three frigates and a number of smaller vessels.[18] The next day, he landed some troops near Tarrytown as a feint to draw Putnam's troops from Peekskill. These troops marched about and then reboarded the ships, which continued north. He then made a similar feinting maneuver at Verplanck's Point, just three miles (4.8 km) south of Peekskill on October 5, where he dislodged a poorly manned American outpost.[19] These feinting maneuvers completely fooled Putnam, who drew his troops back into the eastern highlands and sent messages across the Hudson for reinforcements.

Shortly before this last movement, Sir Henry received a dispatch from Burgoyne. In it, Burgoyne explicitly appeals to Clinton for instruction on whether he should attempt to advance or retreat, based on the likelihood of Clinton's arrival at Albany for support.[19] He indicated that if he did not receive a response by October 12, he would be forced to retreat.[20] (Clinton's response, not written until October 7, was a markedly formal response, indicating that he was providing the requested diversion, and had no expectation of reaching Albany, adding that "Sir Henry Clinton cannot presume to give any Orders to General Burgoyne", as Burgoyne outranked him.[21] Fortunately for Clinton none of the three copies of this letter reached Burgoyne; all of the messengers carrying them were captured.)[21]

Battle

On the foggy morning of October 6, Sir Henry Clinton landed 2,100 men at Stony Point on the west side of the Hudson and, with the assistance of a Loyalist guide, marched them up onto a local rise called the "Timp". After descending the other side to a place called Doodletown, they encountered a scouting party that Governor Clinton had sent out for reconnaissance, which retreated toward Fort Clinton after a brief exchange of fire. Sir Henry then divided his force into two attack groups to take the forts.[22] A force of about 900 men under Lieutenant Colonel Campbell, composed of the 52nd and 57th regiments, a detachment of Hessian chasseurs, and about 400 Loyalists led by Beverley Robinson, began the 7 miles (11 km) trek around the gorge toward Fort Montgomery, while Sir Henry waited with the remaining 1,200 men at Doodletown before starting on the trail to Fort Clinton in order to give Campbell time to make the longer journey before beginning simultaneous attacks on the two forts.[2]

Governor Clinton, when alerted to the first skirmish, had immediately sent to Putnam for reinforcements. Shortly after sending that message he learned from scouts that Sir Henry's forces were divided. While waiting for reinforcements (that never came because of Sir Henry's successful feints) his brother James sent 100 men from Fort Clinton toward Doodletown, while he sent another company from Fort Montgomery to oppose Campbell's force.[2]

Fort Montgomery

The detachment from Fort Montgomery numbered about 100 men, and included a small artillery piece commanded by Captain John Lamb. Setting up a defensive position about one mile (1.6 km) from the fort, they engaged Campbell's tired forces with spirit. While they were eventually forced to retreat, they were able to spike the field piece before abandoning it to the British. After another stand closer to the fort, supported by 12-pound piece, they again retreated (again not before spiking the cannon). Due to this dogged defense, Campbell was not in position until about one hour before sunset (having left Doodletown at around 10 am).[2] Offered the chance to surrender, Governor Clinton refused, and the battle was joined.[23]

Campbell arrayed the Loyalists on the left, the German chasseurs in the center, and the British regiments on the right. Despite vigorous defense and the death of Colonel Campbell, the British forces broke into the fort, where they engaged in a near massacre to avenge the loss of Campbell and other officers.[23] James Clinton narrowly escaped being killed by bayonet when his orderly book deflected the weapon's point. He and a portion of the fort's garrison escaped into the woods north of the fort.[24]

Fort Clinton

The main approach to Fort Clinton was via a narrow strip of land about 400 yards (370 m) wide between a small lake and the river. In addition to being covered by the fort's cannons, Governor Clinton had protected the approach by placing abatis to impeded the British advance.[23] Sir Henry sent the 63rd Foot around the lake to attack the fort from the northwest. At the same time he first sent the light companies of the 7th and 26th regiments and a company of Anspach grenadiers against the main works, followed by the 26th Foot and a detachment from the 17th Light Dragoons, and then the remaining British and German companies. As at Fort Montgomery, the defenders were eventually overwhelmed. Those who surrendered, however, were not subjected to the savagery that took place to the north.[24] A number of the garrison, including General Clinton, escaped by scrambling down the embankment to the river, where gunboats took them to safety across the river.[25]

Aftermath

Casualties

The British casualties were 41 killed and 142 wounded.[4] The Americans had 26 officers and 237 enlisted men captured[4] and about 75 killed and wounded apart from wounded prisoners; most of them from the garrison of Fort Clinton.[3] The Americans were also forced to destroy a number of boats in the area, as unfavorable winds prevented them from escaping upriver. The next day Sir Henry sent a small detachment to Fort Constitution, a small outpost opposite West Point, and demanded its surrender. The lightly manned garrison at first refused, but it retreated on October 8 in the face of a larger attack force.[25]

Governor Clinton and General Putnam strategized on their next move. Clinton opted to move north with troops on the western shore, as a defense against attacks further upriver, while Putnam would take steps to defend against attacks to the east.[25]

Further British action

Captain James Wallace had begun clearing the river of American-laid obstacles following the battle. By October 13 he was able to report that the river was clear as far north as Esopus.[26] Sir Henry had by then returned to New York due to illness, leaving General John Vaughan in charge at the forts. Due to delays in sending transports with reinforcements north, a flotilla carrying Vaughan and 1,700 men did not depart until October 15, with orders from Clinton to "proceed up Hudson's river, to feel for General Burgoyne, to assist his operations".[27] They anchored that evening near Esopus. (It has been speculated that this movement had an effect on the surrender negotiations then ongoing at Saratoga. Due to the slow pace of horse-based communications, it seems unlikely that General Gates was aware of this movement until after the surrender terms were agreed on October 17.)[27] Vaughan's troops burned Esopus the next day, and then sailed further north, where they raided the Livingston estate, seat of the noted Patriot family. The fleet was pursued by Putnam on the eastern shore. Putnam's forces, which had grown considerably due to the arrival of militia companies from Connecticut, posed a significant enough threat to Vaughan that he then withdrew back to the boats.[28]

On October 17, Sir Henry received a request for 3,000 men from General Howe (probably sent after Washington's failed attack on Germantown) to support the occupation of Philadelphia. As the New York garrison was already thinned by the operation on the Hudson, Clinton recalled Vaughan and the garrison holding the two forts. The forts were destroyed and the troops evacuated on October 26.[28]

Legacy

The site of Fort Clinton was largely demolished to make way for U.S. Route 9W and the Bear Mountain Bridge, which was completed in 1924.[29][30] What remains is preserved within the bounds of Bear Mountain State Park, which also includes the ghost town of Doodletown.[31] Fort Montgomery is a National Historic Landmark, a designation it received in 1972, when it was also placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[32][33] It is now located in the Fort Montgomery State Historic Site.[34]

Notes

- Nickerson (1967), p. 347

- Nickerson (1967), p. 348

- Carrington (1876), p. 359

- Clinton, p. 77

- Ketchum (1997), p. 348

- Ketchum (1997), p. 87

- Ketchum (1997), p. 82

- Ketchum (1997), p. 283

- Nickerson (1967), p. 340

- Nickerson (1967), p. 320

- "American War of Independence, 1775–1783". 2007-12-14. Archived from the original on 2007-12-14. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 334–336

- Roseberry (1981), p. 239

- Nickerson (1967), p. 337

- Nickerson (1967), p. 343

- Nickerson (1967), p. 338

- Nickerson (1997), p. 341

- Ketchum (1997), p. 383

- Nickerson (1967), p. 344

- Nickerson (1967), p. 345

- Ketchum (1997), p. 384

- Nickerson (1967), pp. 346–347

- Nickerson (1967), p. 349

- Nickerson (1967), p. 350

- Nickerson (1967), p. 351

- Nickerson (1967), p. 391

- Nickerson (1967), p. 392

- Nickerson (1967), p. 405

- Severo (1998)

- NYS Bear Mountain Bridge page

- Bear Mountain attractions brochure

- Fort Montgomery NHL summary listing

- National Register Information System

- Fort Montgomery National Historic Site main page

References

- Carrington, Henry Beebee (1876). Battles of the American revolution, 1775–1781: historical and military criticism, with topographical illustration. A.S. Barnes. OCLC 191278171.

- Clinton, Henry (1954). The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton's Narrative of his Campaigns, 1775–1782. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1997). Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-6123-9. OCLC 41397623.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2000). Saratoga 1777: Turning Point of a Revolution. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-862-4. OCLC 43419003.

- Nickerson, Hoffman (1967) [1928]. The Turning Point of the Revolution. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat. OCLC 549809.

- Roseberry, Cecil R (1981). From Niagara to Montauk: the scenic pleasures of New York State. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-496-9.

- Savas, Theodore P; Dameron, J. David (2006). A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution. New York: Savas Beattie. ISBN 978-1-932714-12-8.

- Severo, Richard (May 24, 1998). "Revolutionary Fort Held Hostage to Decay and Apathy". The New York Times.

- "Fort Montgomery". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-12. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "Fort Montgomery State Historic Site". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on 2011-08-26. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- "Bear Mountain Bridge". New York State Bridge Authority. Archived from the original on 2009-01-10. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- "Bear Mountain Attractions brochure" (PDF). Palisades Parks Conservancy. Retrieved 2009-05-16.