Battle of Kunersdorf

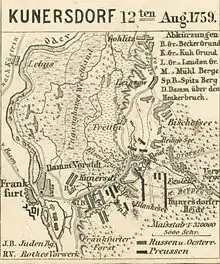

The Battle of Kunersdorf occurred on 12 August 1759 near Kunersdorf (now Kunowice, Poland) immediately east of Frankfurt an der Oder (the second-largest city in Prussia). Part of the Third Silesian War and the wider Seven Years' War, the battle involved over 100,000 men. An Allied army commanded by Pyotr Saltykov and Ernst Gideon von Laudon that included 41,000 Russians and 18,500 Austrians defeated Frederick the Great's army of 50,900 Prussians.

| Battle of Kunersdorf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Silesian War | |||||||

Battle of Kunersdorf, Alexander Kotzebue | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 60,500[1] | 50,900[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 13,477[3]-15,700[4] killed, wounded, captured, and missing | 19,100–21,000 killed, wounded, captured, and missing[5] | ||||||

The terrain complicated battle tactics for both sides, but the Russians and the Austrians, having arrived in the area first, were able to overcome many of its difficulties by strengthening a causeway between two small ponds. They had also devised a solution to Frederick's deadly modus operandi, the oblique order. Although Frederick's troops initially gained the upper hand in the battle, the sheer number of Allied troops gave the Russians and Austrians an advantage. By afternoon, when the combatants were exhausted, fresh Austrian troops thrown into the fray secured the Allied victory.

This was the only time in the Seven Years' War that the Prussian Army, under Frederick's direct command, disintegrated into an undisciplined mass. With this loss, Berlin, only 80 kilometers (50 mi) away, lay open to assault by the Russians and Austrians. However, Saltykov and Laudon did not follow up on the victory due to disagreement. Only 3,000 soldiers from Frederick's original 50,000 remained with him after the battle, although many more had simply scattered and rejoined the army within a few days. This represented the penultimate success of the Russian Empire under Elizabeth of Russia and was arguably Frederick's worst defeat.

Seven Years' War

Although the Seven Years' War was a global conflict, it took on a specific intensity in the European theater based on the recently concluded War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle gave Frederick II of Prussia, known as Frederick the Great, the prosperous province of Silesia as a consequence of the First and Second Silesian Wars. Empress Maria Theresa of Austria had signed the treaty to gain time to rebuild her military forces and forge new alliances; she was intent upon regaining ascendancy in the Holy Roman Empire as well as reacquiring Silesia.[6] In 1754, escalating tensions between Great Britain and France in North America offered France an opportunity to break the British dominance of Atlantic trade. Recognizing the opportunity to regain her lost territories and to limit Prussia's growing power, the Empress put aside the old rivalry with France to form a new coalition. Faced with this turn of events, Britain aligned herself with the Kingdom of Prussia; this alliance drew in not only the British king's territories held in personal union, including Hanover, but also those of his and Frederick's relatives in the Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg and the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel. This series of political maneuvers became known as the Diplomatic Revolution.[7][8][9]

At the outset of the war, Frederick had one of the finest armies in Europe: his troops—any company—could fire at least four volleys a minute, and some of them could fire five.[10] By the end of 1757, the course of the war had gone well for Prussia, and poorly for Austria. Prussia had achieved spectacular victories at Rossbach and Leuthen and reconquered parts of Silesia that had fallen to Austria.[11] The Prussians then pressed south into Austrian Moravia. In April 1758, Prussia and Britain concluded the Anglo-Prussian Convention in which the British committed an annual subsidy of £670,000. Britain also dispatched 7,000–9,000 troops[Note 1] to reinforce the army of Frederick's brother-in-law, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. Ferdinand evicted the French from Hanover and Westphalia and re-captured the port of Emden in March 1758; he crossed the Rhine with his own forces, causing general alarm in France. Despite Ferdinand's victory over the French at the Battle of Krefeld and his brief occupation of Düsseldorf, the successful maneuvering of larger French forces required him to withdraw across the Rhine.[12][13]

While Ferdinand kept the French occupied, Prussia had to contend with Sweden, Russia, and Austria, all of which wanted to carve out a piece of Prussia for themselves. Prussia could lose Silesia to Austria, Pomerania to Sweden, Magdeburg to Saxony, and East Prussia to Poland or Russia: an entirely nightmarish scenario.[14] By 1758, Frederick was increasingly concerned by the Russian advance from the east and marched to counter it. Just east of the Oder river in Brandenburg–Neumark, at the Battle of Zorndorf, on 25 August 1758 a Prussian army of 35,000 men fought a Russian army of 43,000.[15] Both sides suffered heavy casualties but the Russians withdrew, and Frederick claimed victory.[16] At the Battle of Tornow a month later, a Swedish army repulsed the Prussian army, but did not move on Berlin.[17] By late summer, fighting had resulted in a draw. None of Prussia's enemies seemed willing to take the decisive steps to pursue Frederick into Prussia's heartland.[18] The Austrian Feldmarshalleutnant Leopold Josef Graf Daun could have ended the war in October at Hochkirch, but he failed to follow up on his victory with a determined pursuit of Frederick's retreating army. This allowed Frederick time to recruit a new army over the winter.[19]

Situation in 1759

By 1759, Prussia had reached a strategic defensive position; Russian and Austrian troops surrounded Prussia, although not quite at the borders of Brandenburg. Upon leaving winter quarters in April 1759, Frederick assembled his army in Lower Silesia; this forced the main Habsburg army to remain in its staging area in Bohemia. The Russians, however, shifted their forces into western Poland–Lithuania, a move that threatened the Prussian heartland, potentially Berlin itself. Frederick countered by sending Generalleutnant Friedrich August von Finck's army corps to contain the Russians. Finck's corps was defeated at the Battle of Kay on 23 July. Subsequently, Pyotr Saltykov and the Russian forces advanced 110 kilometers (68 mi) west to occupy Frankfurt an der Oder, Prussia's second largest city, on 31 July (on Germany's border with present-day Poland). There he ordered entrenchment of their camp to the east, near Kunersdorf. To make matters worse for the Prussians, an Austrian corps commanded by Feldmarshalleutnant Ernst Gideon von Laudon joined Saltykov on 3–5 August. King Frederick rushed from Saxony, took over the remnants of Generalleutnant Carl Heinrich von Wedel's contingent at Müllrose and moved toward the Oder River. By 9 August, he had 49,000–50,000 troops, enhanced by Finck's defeated corps, and Prince Henry of Prussia's corps moving from the Lausitz region.[20]

Preliminaries

Terrain

The terrain surrounding Kunersdorf suited itself better to defense than offense. Between the Frankfurt dam, a long earthen bulwark that helped to contain the Oder river, and to the north of Kunersdorf itself stretched a 3 km (2 mi) line of knolls; Judenberge (Jews Hill), Mühlberge (Mill Hill) and Walkberge (also spelled Walckberge). None was more than 30 m (98 ft) high. The hillocks were steeper on the north side than the south, but bounded by a marshy, boggy meadow called the Elsbusch, or the Alder wasteland. East of Kunersdorf and the Walkberge, the Hühner Fliess (Fliess means running water) was joined by another stream that tumbled between two more hillocks. Past the Walkberge and beyond the Hühner stood two more promontories at Trettin.[21]

Several ravines intersected the ridge of hillocks: starting at the northeastern end, the Bäckergrund joined the Hühner Fleiss. Just east of the Walkberge a small ravine separated the Walkberge from the Mühlberge. Another narrow roadway cut through the Mühlberge ridge, then a second narrow depression, known as the Kuhgrund (cow hollow), lay west of that. Beyond the Kuhgrund, the ground rose again, then dipped into a fourth hollow in which lay a Jewish settlement known as a shtetl, and the ground rose into the Judenberge; from this point, one could overlook most of Frankfurt and its suburbs. To the southeast lay a variety of small promontories, called the Grosser- and Kleiner-Spitzberge. Like the northwest side of the ridge, this ground was covered with small ponds, streams, marshy fields, and broad meadows. Natural features—ponds, causeways, swamps—would restrict wide movements on some of the terrain.[22] To the east and north of the entire landscape lay the Forest of Reppen. Here the ground itself was sandy and unstable. The scrub forests were threaded with streams, springs, and bogs of all kinds.[23]

Allied dispositions

The Russian army, which before the battle of Kay had about 40,000 men and lost 4800 in the battle, after the battle of Kay had about 35,000 men. After the battle of Kay, it was joined by the Rumyantsev corps of 7,000 men and the Austrian army of General Laudon. On August 4, 1759, according to the inspection, the total number of the Russian army was 41,248 people.[24] This number included the regular army of 33,000 people and irregular—about 8,000 light cavalry of the Cossacks and Kalmyks. During the battle of Kunersdorf Saltykov left a detachment of 266 men in Frankfurt and had 41,000 for the battle. The Austrian army had on 4 August 18,523 men. These figures are reflected in the documents and are used in Russian scientific literature. There are also numerous overestimates of the Russian army, originating from German and English sources—for example 79,000,[25] 64,000,[26] 69,000 and even 88,000[27]—these numbers are not based on documents. For example, the number 79,000 comes from the addition of 55,000 Russians and 24,000 Austrians, and 55,000 Russians are, in turn, the result of an army that had an initial strength of 60,000 people, lost about 5,000 at the battle of Kay. In fact, 60,000 is the total number of all Russian troops in Prussia, including garrisons in different cities, troops for the protection of communications and so on.

A portion of the Russian force remained in Frankfurt as the Allied advanced guard.[1] Saltykov had expected the Austrian commander-in-chief's entire army to arrive; instead a mere wing under Laudon's command came to his aid. Their collaboration was complicated by their personalities. Neither Laudon nor Saltykov had great command of operational arts. Saltykov did not like foreigners; Laudon thought Saltykov was inscrutable. Neither liked conversing through translators, and both mistrusted each other's intentions.[28]

Laudon wanted a fight, so he swallowed his differences and joined the Russians in building fortifications.[28] Saltykov established his troops on a strong position from which to receive the Prussian attack, concentrating his force in the center, which he calculated was the best way to counter-act any attempt by Frederick to deploy his deadly oblique order.[29] Saltykov entrenched himself in a position running from the Judenberge through the Grosser Spitzberge to the Mühlberge, creating a bristling line of fortifications,[30][31] and faced his troops to the northwest; the Judenberge, most heavily fortified, fronted what he believed would be Frederick's approach. He and the Austrian troops were stretched along the ridge that ran from the outskirts of Frankfurt to just north of the village of Kunersdorf.[23] Anticipating that Frederick would rely on his cavalry, the Russians effectively negated any successful cavalry charge by using fallen trees to break up the ground on the approaches.[32]

Saltykov had little concern about the extreme northwestern face of the ridge, which was steep and fronted by the marshy Elsbruch, but a few of the Austrian contingents faced northwest as a precaution.[23] He expected Frederick to attack him from the west, from Frankfurt, and from the Frankfurt outer city. The Russians constructed redans and flèche to protect all the potentially weak points of their fortifications; they built glacis to cover the most shallow of the hills, and scarps and counterscarps to protect seemingly weak points. Abatis not only littered the hillsides, but dotted flat ground. By 10 August, his scouts had told him that Frederick was at the far western edge of Frankfurt.[33] Accordingly, Saltykov took everything he could from the city by way of sustenance, all oxen, sheep, chickens, produce, wine, beer, in a flurry of ransacking.[21]

Prussian plans

While Saltykov plundered the city and prepared for Frederick's assault from the west, the Prussians reached Reitwein, some 28 km (17 mi) north of Frankfurt on 10 August, and built pontoon bridges during the night. Frederick crossed the Oder in the night and the next morning, and moved southward toward Kunersdorf; the Prussians established a staging area near Göritz (also spelled Gohritz on the old maps), about 9.5 km (6 mi) north-northeast of Kunersdorf late on 11 August with about 50,000 men; of these, 2,000 were deemed unfit for service and stayed behind to guard the baggage.[34]

Frederick conducted a perfunctory reconnaissance of his enemy's position, accompanied by a forest ranger and an officer who had previously been stationed in Frankfurt.[35] He also consulted a peasant who, though garrulous, was uninformed about military needs: the peasant told the King that a natural obstacle between the Red Grange (a large farmstead between Kunersdorf and Frankfurt's outer city) and Kunersdorf was unpassable; what the peasant did not know was that the Russians had been there long enough to construct a causeway linking these two sections. Looking to the east through his telescope, Frederick saw some wooded hills, called the Reppen Forest, and he believed he could use them to screen an advance, much like he had done at Leuthen. He did not send scouts to reconnoiter the land or question locals about the ground in the forest. Furthermore, through his glass he could see that the Russians were facing west and north, and their fortifications were stronger on the west. He decided all the Allies were facing northwest and that the forest was readily passable.[33]

After his perfunctory reconnaissance, Frederick returned to his camp to develop his battle plan. He planned to direct a diversionary force, commanded by Finck, to the Hühner Fliess, to demonstrate in front of what he believed to be the main Russian line. He would march with his main army to the southeast of the Allied position, circling around Kunersdorf, screened by the Reppen Forest. This way, he thought, he would surprise his enemy, forcing the Allied army to reverse fronts, which is a complicated maneuver for even the best trained troops. Frederick could then employ his much feared oblique battle order, feinting with his left flank as he did so. Ideally, this would allow him to roll up the Allied line from the Mühlberge.[33]

Final dispositions

Late in the afternoon on the 11th, wily Saltykov realized Frederick was not advancing on him from Frankfurt, and changed his plans. He inverted his flanks: instead of having the left wing at the shtetl and the right at Mühlberge, he reversed his flank with the right at the shtetl.[33] Then the Russians set fire to Kunersdorf. Within hours, the only thing left was the stone church and some walls. While Frederick developed his plan to outflank Saltykov by maneuvering behind him, Saltykov outfoxed him.[33][35][36]

Battle

Prussian activities began at 2:00 am on 12 August. Troops were roused and, within the hour, they set off. Finck's corps had the shortest distance to travel, and the five brigades arrived at the assigned post, the high ground northeast of the Walkeberge, by dawn; Karl Friedrich von Moller established the artillery park on the highest ground at Trettin, and pointed it at the Walkberge, on the hills north of the Hühner Fleiss. Finck's infantry and cavalry demonstrated in front of the five Russian regiments as a diversion, while the remainder of Frederick's army continued in a 37 km (23 mi) semi-circle around the eastern flank of the Russian line, to approach from the village from the southeast. The grueling march took up to eight hours.[37][38] Frederick intended to flank his opposition, and attack what he assumed would be its weakest side, but again, he sent no reconnaissance, not a single hussar or dragoon, to confirm his assumptions.[39]

Mid-way in the march, Frederick finally realized he would end up facing his enemy, instead of approaching from behind. Furthermore, a row of ponds forced him to break his line into three narrow columns, exposing it to full Russian fire power.[40] Frederick changed his dispositions; the Prussian right vanguard would concentrate east of the ponds of Kunersdorf and make an assault on the Mühlberge. Frederick calculated that he could turn the Austrian-Russian flank, and push the Russians off the Mühlberge heights. His redeployment took time, and the apparent hesitation in the assault confirmed to Saltykov what Frederick planned; he moved more troops around so the strongest line would face the Prussian onslaught.[41]

Frederick's army became bogged down in the Reppen Forest. The day was already hot and sultry, and the men were already tired. The trees were thick and the ground was unstable and oozy in some parts, which made the movement of the heavy guns difficult. Delay after delay slowed them down. The carriages pulling the biggest guns, traveling with the bulk of the army, were too wide to cross the narrow forest bridges and the columns had to be reshuffled in the woods. The Russians could hear them, but thought they were scouting parties, albeit noisy ones; they calculated Finck's column was the primary force. Between 5:00 am. and 6:00 am., only Finck's demonstrating corps, to the north by Trettin, were visible to the Russians. Finck's right wing moved out of the hills toward the mill on Hühner Fleiss; more Prussians from Finck's left and center prepared to attack the Walkberge. Finck's artillery awaited Frederick's signal, but the bulk of Frederick's army still crashed about in the woods.[36]

Assault on the Mühlberge

Finally, at 8:00 am., some of Frederick's army emerged from the woods, with most of Generalleutnant Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz's cavalry and the rest of his artillery; a short time later, the rest of the Prussians emerged from the woods, and the Russians realized it was not a scouting party, but the main army. The Prussians stood ranked for battle, which now began in earnest. Finck's artillery park had been in place since dawn and, at 11:30 am, Moller initiated bombardment of the Russian position from the northern and northeastern ends of the Russian line (now the Russian left). In error, the Russian artillery had faced their batteries to the meadows beyond the Mühlberge, not the ravine, and had to be reset. For 30 minutes, the two sides bombarded each other.[42]

At about noon, Frederick sent his first wave of soldiers toward the Russian position on the Mühlberge. Frederick favored mixed troops in such conditions, and his forward troops included grenadiers and musketeers, and some cuirassiers. The Prussian artillery batteries created an arc of fire on the Russian sector by the Walkberge and the Kleiner Spitzberge; the infantry could safely move under this arc. They advanced into the crevasse between the two hills; when they came within 34 m (112 ft) of the Russian guns on the Mühlberge, they charged at point-blank range. Some of Shuvalov's Observation Corps, stationed on the summit, took substantial losses—perhaps 10 percent—before the Prussian grenadiers overwhelmed them.[Note 2][40] Prussian losses were also high. Frederick sent 4,300 men into this assault, immediately losing 206 of Prince Henry's cuirassiers. Although Saltykov sent his own grenadiers to shore up the Russian defense, the Prussians carried the Mühlberge, capturing between 80 and 100 enemy cannons, which they immediately deployed against the Russians. For the moment, the Prussians held the position.[40][42]

After capturing the cannons, the Prussians raked the retreating Russians with fire from their own pieces. The Russians were slaughtered by the score, losing most of five large regiments to injury and death. By 1:00 pm, the Russian left flank had been defeated and driven back on Kunersdorf itself, leaving behind small, disorganized groups capable of only token resistance. In panic, some of the Russians even fired on the Margrave of Baden-Baden's troops, which also wore blue coats (although of a lighter blue), mistaking them for Prussians. Saltykov fed in more units, including a force of Austrian grenadiers led by Major Joseph De Vins, and gradually the situation stabilized.[41]

Attack stalled

The Prussian position at Kunersdorf was not substantially better than it had been a few hours earlier, but it was, at least, defensible; the Russian position, on the other hand, was substantially worse. While Frederick's principal force had assaulted the Mühlberge, Johann Jakob von Wunsch, with 4,000 men, had retraced his steps from Reitwein to Frankfurt and had captured the city by mid-day.[43] The Prussians had effectively blocked the Allies from moving east, west or south, and the terrain blocked them from moving north; if they tried such a foolhardy move, Moller's artillery would rake them with enfilade fire. The King's brother, Prince Henry, and several other generals encouraged Frederick to stop there. The Prussians could defend Frankfurt from their vantage point on the Mühlberge and in the city itself. To descend into the valley, cross the Kuhgrund and ascend Spitzberge against frightful fire was foolhardy, they argued. Furthermore, the weather was blisteringly hot and the troops had endured forced marches to reach the theater and the battlefield. They were exhausted and low on water. The men had not had a hot meal in several days, having bivouacked the night before without fires.

Despite those arguments, Frederick wanted to press his initial success. He had won half the battle and wanted the whole victory. He decided to continue the fight.[44] He transferred his artillery to the Mühlberge, and ordered Finck's battalions to assault the Allied salient from the northwest, while his main strike force would cross the Kuhgrund.[33][40][45]

To complete Frederick's battle plan, the Prussians would have to descend from the Mühlberge to the lower Kuhgrund, cross the spongy field, and then assault the well-defended higher ground.[33] This is where Saltykov had concentrated his men, making the Grosser Spitzburg nearly impregnable. At this point in his plan, Frederick intended to have the second half of a pincer movement ready to squeeze the Russian left. The rearmost forces were supposed to have advanced straight against the Russians from the south, while the right wing did the same from the north. The right was where it was supposed to be, with the exception of one of the support formations for the right wing, which was held up by misinformation about the ground: a couple of bridges that crossed the Huhner Fleiss were too narrow for the artillery teams. The left was still out of position.[41]

Anticipating Frederick's plan, Saltykov had reinforced the salient with reserves from the west and southwest; these reserves included most of Laudon's fresh infantry.[44] Finck made no progress at the salient and the Prussian attack at the Kuhgrund was thwarted with murderous fire along their very narrow front.[40] Watching from the luxury of the Kleiner Spitzberge immediately east of the village, Saltykov judiciously fed in reinforcements from other sectors, and awaited results. Once, in the fierce fighting, it looked like the Prussians might break through, but gradually the Allied superiority of 423 artillery pieces could be brought to bear on the struggling Prussians. The Allied grenadiers held their lines.[44]

The Prussian left had been held up by a variety of problems, mostly relating to the inadequately-scouted terrain. Two small ponds and several streams trisected the ground between the Prussian front and the Russians, which the Russians had also littered with abatis. Tats required the Prussian line to break into small columns that could march along narrow passages between the water and marshy ground, diminishing the legendary firepower of the Prussian line of attack. Outside the shtetl, the Prussians tried to break through the Russian line; they got as far as the Jewish cemetery at the eastern base of Judenberge, but lost two thirds of Krockow's 2nd Dragoons in the process: 484 men and 51 officers gone in minutes.

The 6th Dragoons lost another 234 men and 18 officers as well.[41] Other regiments battling through the Russians and the terrain had comparable losses. Despite these problems, they continued to slog through the Russian positions, advancing toward the Kuhgrund outside what remained of Kunersdorf's wall.[46]

Cavalry attack

The battle culminated in the early evening hours with a Prussian cavalry charge, led by von Seydlitz, upon the Russian centre and artillery positions, a futile effort. The Prussian cavalry suffered heavy losses from cannon fire and retreated in complete disorder. Seydlitz himself was badly wounded and, in his absence, Generalleutnant Dubislav Friedrich von Platen assumed command. Under Frederick's orders,[47] Platen organized a last-ditch effort. His scouts had discovered a crossing past the chain of ponds south of Kunersdorf, but it lay in full view of the artillery batteries on the Grosser Spitzberge. Seydlitz, still following the action, noted that it was foolish to charge a fortified position with cavalry. His assessment was correct,[44] but Frederick had apparently lost his ability to think objectively.[47]

The strength of Frederick's cavalry lay in its ability to attack at a full gallop, with riders knee to knee and horses touching at the shoulders. The units sent against the position shattered; they had to attack piecemeal because of the manner in which the ground was naturally formed. Before any further action could take place, Laudon himself led the Austrian cavalry's counterattack around the obstacles and routed Platen's cavalry. The fleeing men and horses trampled their own infantry around the base of the Mühlberge. General panic ensued.[44]

The cavalry attack against fortified positions had failed.[40] The Prussian infantry had been on its feet for 16 hours, half that in a forced march over muddy and uneven terrain, and the other half in slogging battle against formidable odds, in hot weather.[48] Despite the apparent futility, the Prussian infantry repeatedly attacked the Spitzberge, each time with greater losses; the 37th Infantry lost 992 men and 16 officers, more than 90 percent of its force.

The King himself led two attacks of the 35th Infantry and lost two of his horses in the effort. He was mounting a third when the animal was shot in the neck and fell to the ground, nearly crushing the King. Two of Frederick's adjutants pulled him from under the horse as it fell. A ball smashed the gold snuff box in his coat, and this box, plus his heavy coat,[49] probably saved his life.[47]

Evening action

By 5:00 pm, neither side could make any gains; the Prussians held tenaciously to the captured artillery works, too tired to even retreat: they had pushed the Russians from the Mühlberge, the village, and the Kuhgrund, but no further. The Allies were in a similar state, except they had more cavalry in reserve and some fresh Austrian infantry. This part of Laudon's forces, late arrivals to the scene and largely unused, came into action at about 7:00 pm. To the exhausted Prussians holding the Kuhgrund, the swarm of fresh Austrian reserves was the final stroke. Although such isolated groups as Hans Sigismund von Lestwitz's regiment put up a bold front, these groups lost heavily and their stubborn defense could not stop the chaos of the Prussian retreat. Soldiers threw their weapons and gear aside and ran for their lives.[50]

The battle was lost for Frederick—it had actually been lost for the Prussians for a couple of hours—but he had not accepted this fact. Frederick rode among his melting army, snatched a regimental flag,[51] trying to rally his men: Children, my children, come to me. Avec moi, Avec moi! They did not hear him, or if they did, they chose not to obey.[47] Watching the chaos and seeking the coup de grâce, Saltykov threw his own Cossacks and Kalmyks (cavalry) into the fray. The Chuguevski Cossacks surrounded Frederick on a small hill, where he stood with the remnants of his body-guard—the Leib Cuirassiers—determined to either hold the line or to die trying. With a 100-strong hussar squadron, Rittmeister (cavalry captain) Joachim Bernhard von Prittwitz-Gaffron cut his way through the Cossacks and dragged the King to safety. Much of his squadron died in the effort. As the hussars escorted Frederick from the battlefield, he passed the bodies of his men, lying on their faces with their backs slashed open by Laudon's cavalry. A dry thunderstorm created a surreal effect.[48][52][53]

Aftermath

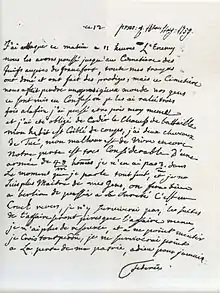

That evening back in Reitwein, Frederick sat in a peasant hut and wrote a despairing letter to his old tutor, Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein:

This morning at 11 o'clock I have attacked the enemy. ... All my troops have worked wonders, but at a cost of innumerable losses. Our men got into confusion. I assembled them three times. In the end I was in danger of getting captured and had to retreat. My coat is perforated by bullets, two horses of mine have been shot dead. My misfortune is that I am still living ... Our defeat is very considerable: To me remains 3,000 men from an army of 48,000 men. At the moment in which I report all this, everyone is on the run; I am no more master of my troops. Thinking of the safety of anybody in Berlin is a good activity ... It is a cruel failure that I will not survive. The consequences of the battle will be worse than the battle itself. I do not have any more resources, and—frankly confessed—I believe that everything is lost. I will not survive the doom of my fatherland. Farewell forever![49]

Frederick also decided to turn over command of the army to Finck. He told this unlucky general he was sick. He named his brother as generalissimo and insisted his generals swear allegiance to his nephew, the 14-year-old Frederick William.[54]

Casualties

Before the battle, both armies had been reinforced by smaller units; by the time of the battle, the Allied forces had about 60,000 men, with another 5,000 holding Frankfurt, and the Prussians had almost 50,000. The Russians and Austrians lost about 15,000 men (approx. 5,000 killed), although some sources suggest a slightly higher number, perhaps 15,600 or 15,700, about 26 percent.[55][4] Christopher Duffy places Russian losses at 13,477; in addition, the Russians had lost about 4,000 at the Battle of Kay a week earlier.[3] Sources differ on Prussian losses. Duffy maintains 6,000 killed and 13,000 wounded, a casualty rate of more than 37 percent.[56] Gaston Bodart represents losses at 39 percent,[55] and that two thirds (12,000)[57] of the 19,000 casualties were deaths.[3] Frank Szabo places Prussian losses at 21,000.[58] Following the battle, the victorious Cossack troops plundered corpses and slit the throats of the wounded; this no doubt contributed to the death rate.[59]

The Prussians lost their entire horse artillery, an amalgam of cavalry and artillery in which the crews rode horses into battle, dragging their cannons behind them, one of Frederick's notable inventions.[Note 3] The Prussians also lost 60 percent of their cavalry, killed or wounded, animals and men. The Prussians lost 172 of their own cannons plus the 105 they had captured from the Russians in the late morning on the Mühlberge. They also lost 27 flags and two standards.[59][60][Note 4]

Staff losses were significant. Frederick lost eight regimental colonels.[59] Of his senior command, Seydlitz was wounded and had to relinquish command to Platen, nowhere near his equal in energy and nerve; Wedel was wounded so badly he never fought again; Georg Ludwig von Puttkamer, commander of the Puttkamer Hussars, lay among the dead.[61][62] Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, later the inspector general and major general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War,[63] was wounded at the battle.[64] Ewald Christian von Kleist, the famous poet of the Prussian army, was badly injured in the latter moments of the assault on the Walkeberge. By the time he was injured, Major Kleist was the highest-ranking officer in his regiment.[65][66] Generalleutnant August Friedrich von Itzenplitz died of his wounds on 5 September, Prince Charles Anton August von Holstein-Beck on 12 September, and Finck's brigade commander, Generalmajor George Ernst von Klitzing, on 28 October in Stettin.[62] Prussia was at its last gasp and Frederick despaired of preserving much of his remaining kingdom for his heir.[54]

Impact on Russo-Austro alliance

Although still wary of one another, the Russian and Austrian commanders were satisfied with the result of their cooperation. They had outfought Frederick's army in a test of nerve, courage and military skills. Elizabeth of Russia promoted Saltykov to Generalfeldmarschall and awarded a special medal to everyone involved. She also sent a sword of honor to Laudon, but the price of the rout was high: 26 percent Austrian and Russian losses would not usually qualify as a victory. The storming of field works typically resulted in a disproportionate number of killed over wounded. The conclusion of the battle in hand-to-hand struggle also increased casualties on both sides. Finally, subsequent cavalry charges and the stampeding flight of men and horses had caused many more injuries.

Regardless of the losses, Saltykov and Laudon remained on the field with intact armies, and with extant communications between one another.[67] The Prussian defeat remained without consequences when the victors did not capitalize on the opportunity to march against Berlin, but retired to Saxony instead. If Saltykov had sought the coup de grâce in the last hour of the battle, he did not follow through with it.[68]

Within days, Frederick's army had reconstituted itself. Approximately 26,000 men, most of the survivors, were scattered over the territory between Kunersdorf and Berlin. Four days after the battle, though, most of the men turned up at the headquarters on the Oder River or in Berlin, and Frederick's army recovered to a strength of 32,000 men and 50 artillery pieces.[56]

Elizabeth of Russia continued her policy of providing support to Austria, considering it vital to Russian interests, but with decreasing effectiveness. Distance constrained the Russian supply lines,[69] and despite Austrian headquarters' agreement to supply the Russian troops through their own lines, Russian troops took little part in the remaining battles of 1759 and 1760. The Russian army did not fight another major battle until they stormed Kolberg in 1761, allowing the Prussians to focus on the Austrians.[56] In 1762, the death of Elizabeth, and the ascension of her nephew, Peter, an admirer of Frederick's, saved the Prussians[70] when he immediately withdrew Russia from hostilities.[71]

Assessment

Most military historians agree that Kunersdorf was Frederick's greatest, and most catastrophic, loss. They generally attribute it to three major problems: his indifference to the Russian practices of the "art of war", his lack of information about the terrain, and his inability to realize that the Russians had surmounted the obstacles of location. Frederick complicated his fate by violating every principle of war he had espoused in his own writing.[33]

First, Frederick had assumed he could use his trade-mark oblique order attack, but his reconnaissance had been incomplete. The Russians had been there for two weeks, had dug in to prepare for Frederick's arrival, and their fortifications bristled with abatis and guns.[31] When he did arrive, Frederick had made limited efforts to assess the terrain and there was no operational reason for him not to have sent some of his cavalry to scout the area, except, perhaps, that his hussars, previously often used in reconnaissance, were being converted by Seydlitz into heavy cavalry.[35] In the two weeks they had to prepare for the battle, the Russians and the Austrians had discovered, and reinforced, a causeway between the lakes and the marshland that allowed them to present Frederick with a united southeastern front. This effectively cancelled any advantage of the oblique battle order employed so successfully at Rossbach and Leuthen. Furthermore, the Russians utilized several natural defensive positions. The chain of hillocks could be enhanced by the construction of redans; the Russians were able to shape abutments from which to fire down upon the Prussians; they also constructed bastions, especially on the Spitzberge. Despite the murderous fire, Frederick's troops eventually turned the Russian left, but to little benefit. The terrain allowed the Russians and Austrians to form a compact front up to 100 men deep, shielded by the hills and marshes.[67]

Second, Frederick's most egregious mistake was his refusal to consider the recommendations of his trusted staff. Brother Henry, a superb tactician and strategist in his own right, reasonably suggested halting the battle at mid-day, after the Prussians had secured the first height and Wunsch, the city. Wunsch could not move across the river; only one bridge remained, and Laudon's cavalry guarded it fiercely.[72] Regardless, from these vantage points, the Prussians would be unassailable, and eventually, the Austro-Russian force would have to withdraw. Furthermore, Henry argued, the troops were exhausted from several days of marching, the weather was appallingly hot, they did not have enough water, and they had not had a good meal in several days.[73] Instead of holding his secure position, though, Frederick forced his tired troops to descend the hill, cross the low ground, and ascend the next hill, in the face of heavy fire.[33] The Prussian cavalry effort initially drove back the Russian and Austrian squadrons, but the fierce cannon and musketry fire from the united Allied front inflicted staggering losses on Frederick's much-vaunted horsemen. Furthermore, he committed perhaps the gravest of errors in sending his cavalry into battle piecemeal and against entrenched positions.[67]

Third, he acted on the ground of his enemy's choosing, not of his own, and on the basis of meager information and almost no understanding of the ground, he broke all the military tactical rules of his own devising. He had thrown his infantry into the teeth of gun fire; he compounded this folly by committing his cavalry piecemeal in pointless charges across soft, spongy ground that was divided by streams, requiring them to attack in long, drawn out lines, rather than en masse; of course, he could not send his cavalry en masse because several natural features—ponds, causeways, swamps—made this impossible on some of the terrain.[22]

The catastrophic loss was due to more than these three issues, though. Indeed, he violated his own rules of strategy and tactics because he faced an enemy he despised, and this brought out the worst of his generalship.[74] In this way, the loss at Kunersdorf was similar to that of the Battle of Hochkirch. There, the British envoy traveling with the Prussian Army attributed Frederick's loss to the contempt in which he held the Austrians and his unwillingness to give credit to intelligence that did not agree with his imagination;[75] certainly, this contempt for the Austrians and the Russians contributed to his loss at Kunersdorf as well.[50] Yet, as Herbert Redman notes, "... seldom in military history has a battle been so completely lost by an organized army in such a short space of time."[50] The loss was not only due to Frederick's unwillingness to accept that the Russians, whom he despised, and the Austrians, whom he despised only slightly less, had any military acumen. At Hochkirch, Frederick demonstrated good leadership by rallying his troops against the surprise attack; Prussian discipline and the bonds of regimental cohesion had prevailed. Importantly, the Prussian army at Kunersdorf was not the same army that had fought at Hochkirch, because it had already fought, and lost, there. Over the winter, Frederick had cobbled together a new army, but it was not as well-trained, well-disciplined, and well-drilled as his old one. He failed to accept this. Arguably Frederick's worst defeat, at Kunersdorf, his army panicked and discipline disintegrated before his eyes, especially in the last hour of the battle. The few regiments that held together, such as that of Lestwitz, were the exception. Frederick had demanded more of his men than they could bear.[54]

Sources

Notes

- Anderson (2007, p. 301) places the total at 7,000; Szabo (2013, pp. 179–182) mentions 9,000.

- Recent archeological excavations in the area suggest that the Prussian assault may have been broader than has been historically assumed: Polish archeologists have discovered the remains of a Russian mounted grenadier, identified by his insignia as a member of the Observation Corps, away from the locus of presumed fighting by the summit, far closer to the mill. The plethora of additional insignia (Prussian and Russian) and the varying kinds of ammunition suggest that intense fighting occurred beyond the narrow assault line originally assumed, and extended well into the meadows beyond the Mühlberge.(Pudruczny & Wrzosek 2014, pp. 45–46).

- Frederick reorganized these mobile batteries later in the year and they participated in the Battle of Maxen, another Prussian loss.(Hedberg 1987, pp. 11–13)

- As an example of the cavalry losses, the Zieten Hussars regimental notations reported: "Dead are Major von Heinicke, Rittmeister von Frankenberg, Lieutenant von Möllendorf, Kornet Offenius. Badly wounded, Rittmeister von Reitzenstein, Lieutenants von Schenk, Korshagen, von Gröben, von Bohlse, and von Schulz, and the Kornet von Schulz. Lightly wounded are nine others; 21 officers are out of action. Of the non commissioned officers and hussars are 140 dead or wounded. 109 horses dead, 65 wounded, 20 missing" (Geschichte 1874, p. 133).

Citations

- Blanning 2016, p. 257.

- Duffy 2015b, p. 189.

- Duffy 1996, p. 235.

- Weigley 2004, p. 191.

- Franz A. J. Szabo. The Seven Years War in Europe: 1756–1763. Routledge. 2013. p. 238

- Wilson 2016, pp. 478–479.

- Horn 1957, pp. 440–464.

- Black 1990, pp. 301–323.

- Berenger 2014, pp. 80–89.

- Anderson 2007, p. 302.

- Asprey 1986, p. 43.

- Szabo 2013, pp. 179–182.

- Anderson 2007, p. 301.

- Simms 2013, p. 99.

- Asprey 1986, pp. 494–499.

- Szabo 2013, pp. 162–169.

- Asprey 1986, p. 500.

- Szabo 2013, pp. 195–202.

- Blanning 2016, p. 253.

- Rink 2014, pp. 727–728.

- Carlyle 1892, p. 250.

- Pudruczny & Wrzosek 2014, pp. 34–35.

- Szabo 2013, p. 236.

- N.Korobkow. Siebenjähriger Krieg 1756–1762. S. 229

- 1759 schlacht kay&f=false Die schlacht bei Kunersdorf am. 12. august 1759

- Studies in Battle Command

- Werner Hahn. Kunersdorf am 12 Aug. 1759

- Showalter 2012, pp. 242–245.

- Weigley 2004, pp. 190–191.

- Showalter 2012, p. 244.

- Pudruczny & Wrzosek 2014, p. 34.

- Pudruczny & Wrzosek 2014, p. 35.

- Szabo 2013, p. 237.

- Showalter 2012, pp. 242–243.

- Showalter 2012, p. 243.

- Redman 2015, pp. 287–289.

- Stephenson n.d., p. 13.

- Redman 2015, p. 289.

- Duffy 2015a, pp. 50–56.

- Holmes & Pimlott 1999, pp. 124–126.

- Redman 2015, p. 291.

- Redman 2015, p. 290.

- Lloyd 1781, p. 145.

- Szabo 2013, p. 238.

- Showalter 2012, pp. 245–246.

- Redman 2015, p. 292.

- Redman 2015, p. 293.

- Duffy 2015b.

- Petersdorff 1911, p. np.

- Redman 2015, p. 294.

- Showalter 2012, p. 247.

- Showalter 2012, pp. 248–250.

- Killy 2005, p. 80.

- Redman 2015, p. 295.

- Bodart & Kellogg 1916, p. 72.

- Wanke 2005, p. 5.

- Bodart & Kellogg 1916, p. 20.

- Franz A. J. Szabo. The Seven Years War in Europe: 1756–1763. Routledge. 2013. p. 238

- Showalter 2012, p. 249.

- Eberhardt 1903, p. 31.

- Poten 1888, pp. 777–779.

- Laubert 1900, p. 93.

- Fleming, Thomas (February–March 2006). "The Magnificent Fraud". American Heritage.

- "General von Steuben". Valley Forge (National Historical Park Pennsylvania). National Park Service. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- Duffy 2015a, p. 52.

- Carlyle 1892, pp. 166–167.

- Langer & Pois 2004, pp. 18–19.

- Showalter 2012, p. 250.

- Lloyd 1781, p. 157.

- Fraser 2001, p. 420.

- Weigley 2004, pp. 192–193.

- Lloyd 1781, p. 150.

- Lloyd 1781, p. 143.

- Langer & Pois 2004, pp. 22–24.

- Blanning 2016, p. 252.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Fred (2007). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-42539-3.

- Asprey, Robert B. (1986). Frederick the Great: The Magnificent Enigma. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 978-0-89919-352-6.

- Berenger, Jean (2014). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1273–1700. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-89569-5.

- Black, Jeremy (1990). "Essay and Reflection: On the 'Old System' and the 'Diplomatic Revolution' of the Eighteenth Century". The International History Review. 12 (2): 301–323. doi:10.1080/07075332.1990.9640547. ISSN 0707-5332.

- Blanning, Tim (2016). Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8129-8873-4.

- Bodart, Gaston; Kellogg, Vernon Lyman (1916). Losses of Life in Modern Wars, Austria-Hungary: France. Clarendon Press. OCLC 875334380.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1892). Frederick the Great. Dana Estes.

- Duffy, Christopher (1996). The Army of Frederick the Great. Emperor's Press. ISBN 978-1-883476-02-1.

- Duffy, Christopher (2015a). Frederick the Great: A Military Life. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-40849-9.

- Duffy, Christopher (2015b). Russia's Military Way to the West: Origins and Nature of Russian Military Power 1700–1800. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-40840-6.

- Eberhardt (1903). Die schlacht von Kunersdorf am 12. august 1759: vortrag gehalten in der Militärischen gesellschaft zu Berlin am 24. jan. 1903 (in German). Ernst Siegfried; Mittler und sohn.

- Fraser, David (2001). Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. Fromm International. ISBN 978-0-88064-261-3.

- Geschichte des Zieten'schen Husaren-Regiments (Brandenburgisches Husaren Regiment Nr. 3 1741–1874) (in German). Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn. 1874. OCLC 924072896.

- Hedberg, Jonas (1987). Kungl. artilleriet: det ridande artilleriet (in Swedish). Militärhistor. Förl. ISBN 978-91-85266-39-5(summary in English)

- Holmes, Richard; Pimlott, John, eds. (1999). The Hutchinson Atlas of Battle Plans: Before and After. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-57958-203-6.

- Horn, D.B. (1957). "The Diplomatic Revolution". In Lindsay, J. O. (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 7, The Old Regime, 1713–1763. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-04545-2.

- Killy, Walther (2005). Dictionary of German Biography (DGB): Plett – Schmidseder. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-096630-5.

- Langer, Philip; Pois, Robert (2004). Command Failure in War: Psychology and Leadership. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-11093-0.

- Laubert, Manfred (1900). Die Schlacht bei Kunersdorf am 12. August 1759 (in German). Mittler. OCLC 823779178.

- Lloyd, Henry (1781). The History of the Late War in Germany. T. and J. Egerton. OCLC 722607771.

- Petersdorff, Herman von (1911). Friedrich der Grosse: ein Bild seines Lebens und seiner Zeit (in German). Gebrüder Paetel. OCLC 678293780.

- Poten, Bernhard von (1888). "Puttkamer, George Ludwig von". In Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ed.). Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German). 26. Duncker & Humblot. pp. 777–779.

- Pudruczny, Grzegorz; Wrzosek, Jakub (9 February 2014). "Lone Grenadier: An Episode from the Battle of Kunersdorf, 12 August 1759". Journal of Conflict Archaeology. 9 (1): 33–47. doi:10.1179/1574077313Z.00000000030. S2CID 162383374. (subscription required)

- Redman, Herbert J. (2015). Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' War, 1756–1763. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7669-5.

- Rink, Martin (2014). "Battle of Kunersdorf". In Zabecki, David T. (ed.). Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 27–728. ISBN 978-1-59884-981-3.

- Showalter, Dennis E. (2012). Frederick the Great: A Military History. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-78303-479-6.

- Simms, Brendan (2013). Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy, from 1453 to the Present. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01333-3.

- Stephenson, Scott (n.d.). "Old Fritz Stumbles: Frederick the Great at Kunersdorf, 1759". Studies in Battle Command. Combat Studies Institute, US Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, KS. pp. 13–20. ISBN 978-1-4289-1465-0.

- Szabo, Franz A.J. (2013). The Seven Years War in Europe: 1756–1763. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-88696-9.

- Wanke, Paul (2005). Russian/Soviet Military Psychiatry, 1904–1945. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-35460-8.

- Weigley, Russell F. (2004). The Age of Battles: The Quest for Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-21707-3.

- Wilson, Peter (2016). Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-91592-3.

Web resources

- Fleming, Thomas (February–March 2006). "The Magnificent Fraud". American Heritage.

- "General von Steuben". Valley Forge (National Historical Park Pennsylvania). National Park Service. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Kunersdorf. |

- Barrow, Stephen A. (2016). Death of a Nation: A New History of Germany. Book Guild Publishing. ISBN 978-1-910508-81-7.

- Carlisle, Thomas (1873). "Chapter 4". History of Friedrich II of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great. Volume 29. Scribner. OCLC 834348912.

- Clark, Christopher (2009). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-190402-3.

- Jomini, General Baron Antoine Henri de (2013). Treatise On Grand Military Operations: Or A Critical And Military History Of The Wars Of Frederick The Great. Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908902-73-3. OCLC 4597887. – particularly Volume 2, Chapter 17

- Jones, Archer (2001). The Art of War in the Western World. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06966-6.

- Kohlrausch, Friedrich (1844). A History of Germany: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. Chapman and Hall. OCLC 610585185. – particularly Chapter XXXI

- Longman, Frederick William (2012). Frederick the Great and the Seven Years' War. Longmans, Green, and Company. ISBN 978-1-245-79345-2.

- Napoleon I (Emperor of the French) (1823). Memoirs of the history of France during the reign of Napoleon. Historical miscellanies, dictated to the count de Montholon. – particularly Chapter 5

- Nolan, Cathal (2017). The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-991099-1.

- Zabecki, David T. (2014). Germany at War: 400 Years of Military History [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-981-3.

Web resources

- Colaiacomo, Alessandro . Battle of Kunersdorf Kronoskaf Seven Years War. Accessed 21 September 2017.