Battle of Lützen (1632)

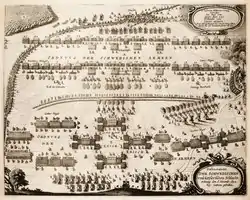

The Battle of Lützen (16 November 1632) was one of the most important battles of the Thirty Years' War.

| Battle of Lützen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years' War | |||||||

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18031.tif.jpg.webp) Death of Gustav II Adolf in the Battle of Lützen painting by C. Wahlbom, 1855 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Protestant German States | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Gustavus Adolphus † Dodo zu Knyphausen Robert Munro Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar |

Albrecht von Wallenstein Gottfried zu Pappenheim (DOW) Heinrich Holk | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

19,000 men 12,800 infantry 6,200 cavalry 60 guns |

22,000 men 10,000 infantry 7,000 cavalry, plus 3,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry on arrival 24 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~10,000 casualties[1] | ~12,000 casualties[1] | ||||||

Lützen Location within Saxony-Anhalt  Lützen Lützen (Germany) | |||||||

Though losses were about equally heavy on both sides, the battle was a Protestant victory, but cost the life of one of the most important leaders of the Protestant side, the Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus, which led the Protestant cause to lose direction. The Imperial field marshal Pappenheim was also fatally wounded.

The loss of Gustavus Adolphus left Catholic France as the dominant power on the "Protestant" (anti-Habsburg) side, eventually leading to the founding of the League of Heilbronn and the open entry of France into the war.

The battle was characterized by fog, which lay heavy over the fields of Saxony that morning. The phrase "Lützendimma" (Lützen fog) is still used in the Swedish language in order to describe particularly heavy fog.

Prelude to the battle

Two days before the battle, on 14 November (in the Gregorian calendar, 4th in the Julian calendar) the Roman Catholic general Albrecht von Wallenstein decided to split his men and withdraw his main headquarters back towards Leipzig. He expected no further move that year from the Swedish army, since unseasonably wintry weather was making it difficult to camp in the open countryside.

However, Gustavus Adolphus' army marched out of camp towards Wallenstein's last known position and attempted to catch him by surprise. This attempted trap was sprung prematurely on the afternoon of 15 November, by a small force left by Wallenstein at the Rippach stream, about 5–6 kilometres south of Lützen. The resulting skirmish delayed the Swedish advance by two or three hours, thus when night fell the two armies were still separated by about 2–3 kilometres (1–2 miles). In their attempt to achieve surprise the Swedes had abandoned the 3-pounder cannons that normally were attached to each of their infantry brigades, denying them the crucial firepower advantage that they had enjoyed in previous battles.[2]

Wallenstein had learned of the Swedish approach on the afternoon of 15 November. Seeing the danger, he dispatched a note to General Pappenheim ordering him to return as quickly as possible with his army corps. Pappenheim received the note after midnight, and immediately set off to rejoin Wallenstein with most of his troops. During the night, Wallenstein deployed his army in a defensive position along the main Lützen-Leipzig road, which he reinforced with trenches. He anchored his right flank on a low hill, on which he placed his main artillery battery.

Battle

Morning mist delayed the Swedish army's advance, but by 9 am the rival armies were in sight of each other. Because of a complex network of waterways and further misty weather, it took until 11 am before the Protestant force was deployed and ready to launch its attack.

Gustavus Adolphus rode his war-horse Streiff, a brown Oldenburg that he had purchased from Colonel Streiff von Lauenstein for the sum of 1000 riksdaler (the sum for a regular horse was about 70-80 riksdaler). Its saddle of gold embroidered red velvet was a gift from the King's wife, Maria Eleonora. Protecting the King's body was a buff coat made of moose hide - the old musket wound on his shoulder blade making it impossible for him to wear the pistol-proof plate cuirass normally worn by important officers at that time. This would have serious consequences later.[3]

Pappenheim's return and fall

Initially, the battle went well for the Protestants, who managed to outflank Wallenstein's weak left wing. After a while, Pappenheim arrived with 2,000–3,000 cavalry and halted the Swedish assault. However, during the charge, Pappenheim was fatally wounded by a small-calibre Swedish cannonball. At the same time, Pappenheim's counterattack collapsed. He died while being evacuated from the field in a coach.

Gustavus Adolphus' disappearance and death

The cavalry action on the open Imperial left wing continued, with both sides deploying reserves in an attempt to gain the upper hand. Soon afterwards, towards 1:00 pm, Gustavus Adolphus was himself killed while leading a cavalry charge on this wing.[4] First, a bullet crushed his left arm below the elbow, while simultaneously his horse suffered a shot to the neck that made it hard to control. In the mix of fog and smoke from the burning town of Lützen the king and his small escort rode astray behind enemy lines and were attacked by a squadron of Imperial cuirassiers. He sustained yet another shot in the back, suffered several sword stabs through the torso and fell from his horse. As he lay dying on the ground, he received a final, fatal shot to the temple.[3]

His fate remained unknown for some time. However, when the gunnery paused and the smoke cleared, his horse was spotted between the two lines, Gustavus himself not on it and nowhere to be seen. His disappearance stopped the initiative of the hitherto successful Swedish right wing, while a search was conducted. His partly stripped body[4] was found an hour or two later, and was secretly evacuated from the field in a Swedish artillery wagon.

Struggle in the center

Meanwhile, the veteran infantry of the Swedish center had continued to follow orders and tried to assault the strongly entrenched Imperial center and right wing. Their attack was a catastrophic failure. A gap opened in the centre of the Swedish line, which was exploited by Imperial cavalry charging from behind the cover of their own infantry. Two of the oldest and most experienced infantry units of the Swedish army, the 'Old Blue' Regiment and the Yellow or 'Court' Regiment were effectively wiped out in these assaults; remnants from them streamed to the rear. Soon most of the Swedish front line was in chaotic retreat.

The royal preacher, Jakob Fabricius, rallied a few Swedish officers around him and started to sing a psalm. This act had many of the soldiers halt in hundreds. The foresight of Swedish third-in-command Major General Dodo zu Innhausen und Knyphausen also helped stanch the rout: he had kept the Swedish second or reserve line well out of range of Imperial gunfire, and this allowed the broken Swedish front line to rally.

Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar

By about 3 PM, the Protestant second-in-command Bernhard of Saxe-Weimar, having learned of the king's death, returned from the left wing and assumed command over the entire army. He vowed to win the battle in retribution for Gustavus or die trying, but contrary to popular legend tried to keep the king's fate secret from the army as a whole. (Although rumours were circulating much earlier, it was only the following day that Bernhard collected his surviving officers together and told them the truth.)

The result was a grim struggle, with terrible casualties on both sides. Finally, with dusk falling, the Swedes captured the linchpin of Wallenstein's position, the main Imperial artillery battery. The Imperial forces retired back out of its range, leaving the field to the Swedes. At about 6 pm, Pappenheim's infantry, about 3,000–4,000 strong, after marching all day towards the gunfire, arrived on the battlefield. Although night had fallen, they wished to counterattack the Swedes. Wallenstein, however, believed the situation hopeless and instead ordered his army to withdraw to Leipzig under cover of the fresh infantry.

After the battle

The body of Gustav II Adolf was plundered of its clothes and gold jewellery and left on the battlefield dressed only in his shirts and long stockings.

His buff coat was taken as a trophy to the emperor in Vienna. It was returned to Sweden in 1920, in recognition of relief efforts by the Swedish Red Cross during and after the First World War.

The king's horse, Streiff, followed the procession with the king's body through northern Germany. When Streiff died at Wolgast in 1633, his hide was saved and sent to Stockholm and Sweden where it was mounted on a wooden model. "The Hero-king's war horse" would soon be displayed in the Royal Armoury as a monument to the King. Today Streiff is permanently displayed in the Royal Armoury in Stockholm, Sweden.[3]

Gustavus Adolphus' funeral cortege from Lützen to Stockholm

After the fateful Battle of Lützen the dead Gustavus Adolphus was first taken to Meuchen to be cleaned and then to Weissenfels for embalming. The embalmed body was dressed in a beautiful gold and silver woven dress and brought in solemn procession to the port town Wolgast. The corpse was kept there for several months. Not until the summer 1633 it was time for the departure to Sweden. The dead king was then brought in a procession down to the sea side. It consisted of people from Sweden and the nearby areas. Banners from all counties and principalities, the blood banner and the head banner were carried. The armor (kyrisset), the sword and the horse (livhästen) functioned as symbols for the dead king. The widow, Maria Eleonora, rode in a coach, but Gustavus Adolphus' young daughter Christina did not participate. The procession ended by the water, where the ship Stora Nyckeln was to bring the dead across the sea to the Swedish town Nyköping.

When the ship arrived to Nyköping, there were rumours of dreadful portents. A shoemaker's wife was said to have given birth to a freak and a calf with two heads had been born. The royal corpse was kept in Nyköping until the funeral in summer 1634. When it was time for the final journey to Stockholm, a ceremony was held at Nyköping Castle where the king's old teacher Johan Skytte held a speech and the bishop Johannes Rudbeckius read a sermon dedicated to the king's daughter Christina.

In the procession to Stockholm there were eight war trophies from Lützen and several trophy banners from Leipzig, marking Sweden's status as a great power. Five black-dressed members of the privy council (riksämbetsmän) carried the regalia before the royal corpse, which lay on a bier adorned with black cloth. Right behind the bier came the king's brother in law, the Count Palatine Johan Casimir with his sons Karl Gustav and Adolf Johan. This time both the grieving Dowager Queen, Maria Eleonora and the king's seven-year-old daughter Christina attended. The sorrowful procession moved slowly across the country towards the capital.

Gustavus Adolphus's funeral in Stockholm 1634

The streets of Stockholm were arranged for the funeral. The burghers had been told to white lime the houses along the procession route and trophies from Lützen and Leipzig had been placed out. On the funeral day, 22 June, the participants gathered outside town. The dead king was taken off his coach and carried into the capital to the Church. Bishops and priests welcomed the procession in the outskirts of the town and along the road from the gate to the church money were thrown to the people. When the procession reached the Riddarholms church the blood banner was placed over the entrance to the tomb and the bier with Gustavus Adolphus was placed in the middle of the choir. A grand ceremony was held by the Bishop Johannes Botvidi, with a sermon dedicated to the Dowager Queen Maria Eleonora. When the ceremony was over the dead king was placed in the tomb. The end of the ceremony was promulgated by cannons firing over the town for two hours.[5][6]

Aftermath

Strategically and tactically speaking, the Battle of Lützen was a Protestant victory. Having been forced to assault an entrenched position, Sweden lost about 6,000 men including badly wounded and deserters, many of whom may have drifted back to the ranks in the following weeks. The Imperial army probably lost slightly fewer men than the Swedes on the field, but because of the loss of the battlefield and general theatre of operations to the Swedes, fewer of the wounded and stragglers were able to rejoin the ranks.

The Swedish army achieved the main goals of its campaign. The Imperial onslaught on Saxony was halted, Wallenstein chose to withdraw from Saxony into Bohemia for the winter, and Saxony continued in its alliance with the Swedes.[7] However, without Gustavus Adolphus to unify the German Protestants, their war effort lost direction. As a result, the Catholic Habsburgs were able to restore their balance and subsequently regain some of the losses Gustavus Adolphus had inflicted on them.

Crucially, Gustavus Adolphus's death enabled the Catholic French to gain much firmer control of the anti-Habsburg alliance. Sweden's new regency was forced to accept a far less dominant role than it had held before the battle. The war was eventually concluded at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

Memorial

Near the spot where Gustavus Adolphus fell, a granite boulder was placed in position on the day after the battle. A canopy of cast iron was erected over this "Swedes' stone" (German: Schwedenstein) in 1832, and close by, a chapel, built by Oskar Ekman, a citizen of Gothenburg (d. 1907), was dedicated on 6 November 1907.[8][9] The fallen king is remembered every year in Sweden, on Gustavus Adolphus Day 6 November, with serene celebrations and special pastries.

Archaeology

In 2011, a mass grave containing the remains of 47 soldiers were found in an area where a Swedish unit known as the Blue Brigade was reportedly defeated in a surprise attack by a Catholic cavalry unit. Examination of the remains determined that more than half of the soldiers had been hit by gunfire, an unusually high number for this time period.[10]

Date

At this time, the Catholic Holy Roman Empire used the Gregorian calendar, but Protestant Sweden still used the Julian calendar. Hence the Battle of Lützen occurred on 16 November for the Catholics but on 6 November for the Swedes. In Sweden, the death of Gustavus Adolphus has a long tradition of being commemorated on 6 November, Gustavus Adolphus Day, despite the country's adoption of the Gregorian calendar in the 18th century.

Napoleon

In May 1813, the Emperor Napoleon was visiting the 1632 battlefield, playing tour guide with his staff by pointing to the sites and describing the events of 1632, in detail from memory. When he heard the sound of cannon, he immediately cut the tour short and went to conduct his own Battle of Lützen.

See also

References

Sources

- Brzezinski, Richard (2001). Lützen 1632: The Clash of Empires. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-552-7.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grönhammar, Ann; Nestor, Sofia (2011) [2007]. The Royal Armoury in the cellar vaults of the Royal Palace. Stockholm: HathiTrust Digital Library. ISBN 978-9187594304.

- Grundberg, Malin (2005). Ceremoniernas makt: Maktöverföring och genus i Vasatidens kungliga ceremonier [The Power of Ceremonies: Power Transfer and Gender in the Vasa era Royal Ceremonies] (in Swedish). Lund: Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-73-9.

- Klussmann, Uwe (26 July 2011). "Der Löwe aus Mitternacht" [The Lion from Midnight]. spiegel.de (in German). Spiegel Online. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Nicklisch, Nicole; et al. (2017). "The face of war: Trauma analysis of a mass grave from the Battle of Lützen (1632)". PLOS One. Public Library of Science, PLOS One. 12 (5): e0178252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0178252. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28542491.

- Rangström, Lena (2015). Dödens teater: Kungliga svenska begravningar genom fem århundraden [Death Theater: Royal Swedish funerals through five centuries] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Atlantis. ISBN 978-91-7353-785-8.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schürger, André (2015). The archaeology of the Battle of Lützen: An examination of 17th century military material culture (Thesis). Glasgow: University of Glasgow. OCLC 936224650.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Vol. 2: 1500 - 1774. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851096671.

- Wedgwood, C.V. (1997) [1938]. The Thirty Years War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-5332-5.

- Weir, William (2004). 50 Battles That Changed the World: The Conflicts That Most Influenced the Course of History. Savage, MD: Barnes & Noble. p. 320. ISBN 0-7607-6609-6.

- Weiss, Daniel (2017). "Last Stand of the Blue Brigade". Archaeology. New York: Archaeological Institute of America. 70 (5): 14. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 31 August 2017 – via Master File Complete at ebsco.com (subscription required)

- anon. "Battle of Breitenfeld". Early 17th century Drill, Illustrated & Animated. syler.com, hosted by Perfect Privacy LLC, FL. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Lützen (1632). |

- The Great and Famous Battle of Lutzen PDF file on aquinas.edu