Battle of Myriokephalon

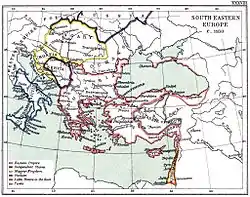

The Battle of Myriokephalon (also known as the Battle of Myriocephalum, Turkish: Miryokefalon Savaşı or Düzbel Muharebesi) was a battle between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Turks in Phrygia in the vicinity of Lake Beyşehir in southwestern Turkey on 17 September 1176. The battle was a strategic reverse for the Byzantine forces, who were ambushed when moving through a mountain pass.

| Battle of Myriokephalon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Byzantine–Seljuq Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Byzantine Empire Kingdom of Hungary Principality of Antioch Principality of Serbia | Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Kilij Arslan II | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000–40,000[3][4] | Unknown (likely smaller) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Approx. 1⁄4 of the army[5] or half of those troops who were directly attacked (left and right wings only),[6] possibly heavy[7][8] | Unknown | ||||||

It was to be the final, unsuccessful effort by the Byzantines to recover the interior of Anatolia from the Seljuk Turks.

Background

Between 1158 and 1161 a series of Byzantine campaigns against the Seljuk Turks of the Sultanate of Rûm resulted in a treaty favourable to the Empire, with the sultan recognising a form of subordination to the Byzantine emperor. Immediately after peace was negotiated the Seljuk sultan Kilij Arslan II visited Constantinople where he was treated by Emperor Manuel I Komnenos as both an honoured guest and an imperial vassal. Following this event there was no overt hostility between the two powers for many years. It was a fragile peace, however, as the Seljuks wanted to push from the arid central plateau of Asia Minor into the more fertile coastal lands, while the Byzantines wanted to recover the Anatolian territory they had lost since the Battle of Manzikert a century earlier.[9]

During the long peace with the Seljuks Manuel was able to concentrate his military power in other theatres. In the west, he defeated Hungary and imposed Byzantine control over all the Balkans. In the east, he recovered Cilicia from local Armenian dynasts and managed to reduce the Crusader Principality of Antioch to vassal status. However, peace with Byzantium also allowed Killij Arslan to eliminate internal rivals and strengthen his military resources. When the strongest Muslim ruler in Syria Nur ad-Din Zangi died in 1174, his successor Saladin was more concerned with Egypt and Palestine than the territory bordering the Empire. This shift in power gave Kilij Arslan the freedom to destroy the Danishmend emirates of eastern Anatolia and also eject his brother Shahinshah from his lands near Ankara. Shahinshah, who was Manuel's vassal, and the Danishmend emirs fled to the protection of Byzantium. In 1175 the peace between Byzantium and the Sultanate of Rûm fell apart when Kilij Arslan refused to hand over to the Byzantines, as he was obliged to do by treaty, a considerable proportion of the territory he had recently conquered from the Danishmends.[10]

March

The army gathered at Lopadion by Manuel was supposedly so large that it spread across ten miles, and marched towards the border with the Seljuks via Laodicea, Chonae, Lampe, Celaenae, Choma and Antioch. Arslan tried to negotiate but Manuel was convinced of his superiority and rejected a new peace.[11] He sent part of the army under Andronikos Vatatzes towards Amasia while his larger force marched towards the Seljuk capital at Iconium (Konya). Both routes were through heavily wooded regions, where the Turks could easily hide and set up ambushes; the army moving towards Amasia was destroyed in one such ambush. The Turks later displayed Andronikos's head, impaled on a lance, during the fighting at Myriokephalon.[12]

The Turks also destroyed crops and poisoned water supplies to make Manuel's march more difficult. Arslan harassed the Byzantine army in order to force it into the Meander valley, and specifically the mountain pass of Tzivritze near the fortress of Myriokephalon. Once at the pass Manuel decided to attack, despite the danger from further ambushes, and also despite the fact that he could have attempted to bring the Turks out of their positions to fight them on the nearby plain of Philomelion, the site of an earlier victory won by his grandfather Alexios. The lack of forage, and water for his troops, and the fact that dysentery had broken out in his army may have induced Manuel to decide to force the pass regardless of the danger of ambush.[13]

Army numbers and organisation

Byzantines

All sources agree that the Byzantine force was of exceptional size. The historian John Haldon estimates the army at 25,000–30,000 men, while John Birkenmeier puts it at around 35,000 men.[3][14] The latter number is derived from the fact that sources indicated a supply train of 3,000 wagons accompanied the army, which was enough to support 30,000–40,000 men.[4] Birkenmeier believes that the army contained 25,000 Byzantine troops with the remainder composed of an allied contingent of Hungarians sent by Manuel's kinsman Béla III of Hungary and tributary forces supplied by the Principality of Antioch and Serbia.[15][16]

The Byzantine army was divided into a number of divisions, which entered the pass in the following order: a vanguard, largely of infantry (the other divisions being composed of a mix of infantry and cavalry); the main division (of eastern and western Tagmata); then the right wing (largely composed of Antiochenes and other Westerners), led by Baldwin of Antioch (Manuel's brother-in-law); the baggage and siege trains; the Byzantine left wing, led by Theodore Mavrozomes and John Kantakouzenos; the emperor and his picked troops; and finally the rear division under the experienced general Andronikos Kontostephanos.[4][17]

Seljuks

No estimates of Seljuk numbers for the battle have been possible. Primary sources have provided figures for other Seljuk campaigns. In 1160, John Kontostephanos defeated a force of 22,000 Seljuk Turks and about 20,000–24,000 Turks invaded the Maeander river valley in 1177.[4][18] However, modern historians have estimated that the various Seljuk successor states (such as the Sultanate of Rum) could field at most 10,000–15,000 men.[19] This is likely a closer estimate for the possible Seljuk strength at Myriokephalon considering the much larger and united Seljuk Empire fielded around 20,000–30,000 men at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.[20] The Sultanate of Rum was much smaller territorially than the Seljuk Empire and probably had smaller armies, for example, its army at the Battle of Dorylaeum in 1097 has been estimated at between 6,000–8,000 men.

The Seljuk army consisted of two main sections: the askars of the sultan and of each of his emirs, and an irregular force of Turkoman tribesmen. The askari (Arabic for 'soldier') was a full-time soldier, often a mamluk, a type of slave-soldier though this form of nominal slavery was not servile. They were supported by payments in cash or though a semi-feudal system of grants, called iqta'. These troops formed the core of field armies and were medium to heavy cavalry; they were armoured, and fought in coherent units with bow and lance. In contrast, the Turkoman tribesmen were semi-nomadic irregular horsemen, who served under their own chieftains. They lived off their herds and served the sultan on the promise of plunder, the ransom of prisoners, for one-off payments, or if their pasturelands were threatened. These tribesmen were unreliable as soldiers, but were numerous, and were effective as light mounted archers, adept at skirmish tactics.[21]

Battle

The Byzantine vanguard was the first to encounter Arslan's troops, and went through the pass with few casualties, as did the main division. Possibly the Turks had not yet fully deployed in their positions.[22] These divisions sent their infantry up onto the slopes to dislodge the Seljuk soldiers, who were forced to withdraw to higher ground. The following divisions did not take this precaution, also they were negligent in not maintaining a defensive formation of closed ranks and they did not deploy their archers effectively.[23] By the time the first two Byzantine divisions exited the far end of the pass, the rear was just about to enter; this allowed the Turks to close their trap on those divisions still within the pass. The Turkish attack, descending from the heights, fell especially heavily on the Byzantine right wing. This division seems to have quickly lost cohesion and been broken, soldiers fleeing one ambush often running into another. Heavy casualties were sustained by the right-wing and its commander, Baldwin, was killed.[24] The Turks then concentrated their attacks on the baggage and siege trains, shooting down the draught animals and choking the roadway. The left-wing division also suffered significant casualties and one of its leaders, John Kantakouzenos, was slain when fighting alone against a band of Seljuk soldiers.[25] The remaining Byzantine troops were panicked by the carnage in front of them and the realisation that the Turks had also begun to attack their rear. The sudden descent of a blinding dust-storm did nothing to improve the morale or organisation of the Byzantine forces, though it must have confused the Seljuk troops also. At this point, Manuel seems to have suffered a crisis of confidence and reputedly sat down, passively awaiting his fate and that of his army.[26]

The emperor was eventually roused by his officers, re-established discipline and organised his forces into a defensive formation; when formed up, they pushed their way past the wreck of the baggage and out of the pass.[26] Debouching from the pass they rejoined the unscathed van and main divisions, commanded by John and Andronikos Angelos, Constantine Makrodoukas and Andronikos Lampardas. Whilst the rest of the army had been under attack in the pass the troops of the van and main divisions had constructed a fortified encampment. The rear division, under Andronikos Kontostephanos, arrived at the camp somewhat later than the emperor, having suffered few casualties.[27]

The night was spent in successfully repulsing further attacks by Seljuk mounted archers.[26] Niketas Choniates states that Manuel considered abandoning his troops but was shamed into staying by the scathing words of an anonymous soldier and the disapproval of a shocked Kontostephanos.[28] However, this would appear to be hyperbole on the historian's part as Manuel would have placed himself in much greater danger by flight than if he remained in the midst of his army. The following day, the Turks circled the camp firing arrows; Manuel ordered two counterattacks, led by John Angelos and Constantine Makrodoukas respectively, but there was no renewal of a general action.[29]

Outcome

Both sides, it appears, had suffered casualties, though their extent is difficult to quantify. Modern historians have postulated that about half of the Byzantine army was engaged and around half of those became casualties.[30][31] As the Byzantine army moved back through the pass after the battle it was seen that the dead had been scalped and their genitals mutilated, "It was said that the Turks took these measures so that the circumcised could not be distinguished from the uncircumcised and the victory therefore disputed and contested since many had fallen on both sides."[32] Most importantly Manuel's siege equipment had been captured and destroyed. The Byzantines, without any means of attacking Iconium, were now no longer in a position to continue the campaign. Also the Seljuk Sultan was keen for peace to be restored as soon as possible; he sent an envoy named Gabras, together with gifts of a Nisaean warhorse and a sword, to Manuel in order to negotiate a truce.[33] As a result of these negotiations, the Byzantine army was to be allowed to retreat unmolested on condition that Manuel destroy his forts and evacuate the garrisons at Dorylaeum and Sublaeum in the Byzantine-Seljuk borderlands.[34] However, despite Kilij Arslan's protestations of good faith, the retreat of the Byzantine army was harassed by the attacks of Turkoman tribesmen (over whom Kilij Arslan probably had very little control). This, taken with an earlier failure by the sultan to keep his side of a treaty signed in 1162, gave Manuel an excuse to avoid observing the terms of this new arrangement in their entirety. He therefore demolished the fortifications of the less important fortress of Sublaeum but left Dorylaeum intact.[35]

Manuel himself compared his defeat to that of Manzikert, sending a message to Constantinople ahead of his army likening his fate to that of Romanos Diogenes. However, in the same message he: "Then extolled the treaties made with the sultan, boasting that these had been concluded beneath his own banner which had waved in the wind in view of the enemy's front line so that trembling and fear fell upon them."[36] It is notable that it was the sultan who initiated peace proposals by sending an envoy to Manuel and not the reverse. The conclusion that Kilij Arslan, though negotiating from a position of strength, did not consider that his forces were capable of destroying the Byzantine army is inescapable. A possible reason for Kilij Arslan's reluctance to renew the battle is that a large proportion of his irregular troops may have been far more interested in securing the plunder they had taken than in continuing the fight, thus leaving his army seriously weakened.[37]

Aftermath

Myriokephalon, although a significant defeat for the Byzantines, did not materially affect the capabilities of the Byzantine army. This is underlined by the notable victory the Byzantines won over the Seljuks at Hyelion and Leimocheir on the Meander River the following year. Ironically, this battle was a reverse of Myriokephalon, with a Seljuk army blundering into a classic ambush laid by the Byzantine general John Komnenos Vatatzes. Manuel continued to meet the Seljuks in smaller battles with some success, and concluded a probably advantageous peace with Kilij Arslan in 1179.[38] However, like Manzikert, Myriokephalon was a pivotal event and following it the balance between the two powers in Anatolia gradually began to shift, and subsequently, Byzantium was unable to compete for dominance of the Anatolian interior.[39]

Myriokephalon had more of a psychological impact than a military impact, as it proved that the Empire could not destroy Seljuk power in central Anatolia, despite the advances made during Manuel's reign. Essentially, the problem was that Manuel had allowed himself to be distracted by a series of military adventures in Italy and Egypt, instead of dealing with the more pressing issue of the Turks. This had given the Sultan many years in which to eliminate his rivals, enabling him to build up a force capable of facing the Byzantine army in the field. Without the years required to build up Seljuk military power, the battle could not have taken place. Furthermore, during the campaign, Manuel made several serious tactical errors, such as failing to scout out the route ahead effectively and ignoring the advice of his senior officers. These failings caused him to lead his forces straight into a classic ambush. However, in defence of Manuel's generalship it is clear that he organised his army in a very effective manner. The army was composed of a number of 'divisions', each of which was self-reliant and could act as a small independent army; it has been argued that it was this organisation which allowed the greater part of his army to survive the ambush inflicted on it.[40]

An important facet of Manuel's dispositions was that the vanguard was composed of infantry. Infantry are far better troops than cavalry when operating in mountainous terrain and it appears that the infantry van was meant to dislodge any Seljuk soldiery from the high ground dominating the pass. They signally failed to sweep the Seljuks from the pass and this failure was a major cause of the Byzantine defeat. Added to this there seems to have been a failure in generalship by the commanders of the right and left wings, who did not deploy their troops as effectively as had the commanders of the two leading divisions.[41]

After Manuel's death, the empire drifted into anarchy, and it was never again in a position to mount a major offensive in the east. The defeat of Myriokephalon marked the end of Byzantine attempts to recover the Anatolian plateau, which was now lost to the empire forever.[42]

See also

References

- Treadgold1997, p. 635.

- The battle was decisive in that it saved the Seljuk Sultanate but the military balance between the two belligerents was not greatly affected by its outcome. The bulk of Byzantine Asia Minor was retained for more than a century after the battle. Magdalino 1993, p. 99. "Whatever he [Manuel] said in the moment of defeat, it was not a disaster on the scale of Manzikert… Even Choniates admits that the frontier in Asia Minor did not collapse."

- Haldon 2001, p. 198.

- Birkenmeier, p. 180.

- Hendy 1985, p. 128.

- Birkenmeier 2002, p. 131.

- Magdalino 1993, p. 98. "The defeat which it suffered in the narrows of Tzibritze, a day's march from Konya, near the ruined fort of Myriokephalon, was correspondingly humiliating. The Turks made great slaughter, took great quantity of booty, and came close to capturing the Emperor himself who gratefully accepted the sultan's offer of a truce in return of demolishing Dorylaion and Sublaion."

- Bradbury 2004, p. 176. "With Manuel were Hungarian allies and his brother-in-law Baldwin of Antioch. Baldwin charged but was killed. The Byzantines suffered heavy losses. Kilij Arslan offered terms and the Byzantines were allowed to withdraw."

- Magdalino, pp. 76–78

- Magdalino, pp. 78 and 95–96

- Angold 1984, p. 192.

- Choniates 1984, p. 103.

- Choniates 1984, p. 101; Haldon 2001, pp. 141–142.

- Birkenmeier, p. 132.

- The Hungarian troops were commanded by Palatine Ampud, and Leustach Rátót, Voivode of Transylvania.Markó, László (2000), Great Honours of the Hungarian State, Budapest: Magyar Könyvklub, ISBN 963-547-085-1

- Birkenmeier, p. 151.

- Choniates 1984, p. 102; Haldon 2001, p. 142.

- Birkenmeier, p. 54.

- Nicolle, p.24

- Haldon, p.85

- Heath (1978), pp. 32-39

- Haldon 2001, p. 142.

- Choniates 1984, p. 102

- Choniates 1984, p. 102; Haldon 2001, pp. 142–143.

- Choniates 1984, p. 104.

- Haldon 2001, p. 143.

- Choniates 1984, p. 105.

- Choniates 1984, pp. 105–106. Manuel may have had the fate of Romanos Diogenes in mind and have had some apprehension of being captured. His situation was, however, very different to that of Diogenes. Unlike the case of the earlier emperor, Manuel's troops had not dispersed from the battlefield but had drawn together following their defeat and were still capable of defending themselves.

- Choniates 1984, p. 106. It is notable that the two generals leading the counterattacks commanded units which had suffered negligible losses the previous day. It is probable that the Byzantine counter-attacks achieved little because, once in open country, the Seljuks were reluctant to come to close combat with the more heavily armoured Byzantine cavalry, and the Byzantines were unwilling to pursue too far for fear of further ambushes.

- Hendy 1985, p. 128.

- Birkenmeier 2002, p. 131.

- Choniates 1984, p. 107. Presumably, the scalping took place because the Turks wore their hair in a distinctive style.

- Choniates 1984, p. 107. The "Gabras" who acted as emissary was possibly Iktiyar ad-Din Hasan ibn Gabras, who was Kilij Arslan's vizier. He was a member of the Gabras family of Greek origin that had ruled Trebizond earlier in the 12th century. There were a number of prominent Greek aristocrats in Seljuk employ, including Manuel's first cousin John Tzelepes Komnenos.

- Angold 1984, pp. 192–193.

- Treadgold 1997, p. 649.

- Choniates 1984, p. 108.

- Finlay 1877, p. 195.

- Angold 1984, p. 193; Magdalino 1993, pp. 99–100.

- Brand, p. 12

- Birkenmeier, p. 132

- Choniates 1984, p. 102.

- Haldon, p. 144

Further reading

Primary sources

- Choniates, Niketas (1984), Historia, English translation: Magoulias, H. (O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniates), Detroit, ISBN 0-8143-1764-2

Secondary sources

- Angold, Michael (1984), The Byzantine Empire 1025–1204: A Political History, Longman, ISBN 978-0-58-249060-4

- Birkenmeier, John W. (2002), The Development of the Komnenian Army: 1081–1180, Boston: Brill, ISBN 90-04-11710-5

- Bradbury, Jim (2004), The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-22126-9

- Brand, Charles M. (1989). "The Turkish Element in Byzantium, Eleventh–Twelfth Centuries". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. Washington, District of Columbia: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. 43: 1–25. doi:10.2307/1291603. JSTOR 1291603.

- Finlay, George (1877), A History of Greece, Volume III, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Haldon, John (2001), The Byzantine Wars, Stroud: Tempus, ISBN 0-7524-1777-0

- Heath, I. (2019) Armies and Enemies of the Crusades 1096-1291, 2nd ed., Wargames Research Group ISBN 9780244474881

- Hendy, Michael (1985), Studies in the Byzantine Monetary Economy c. 300–1450, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-24715-2

- Magdalino, Paul (1993), The Empire of Manuel I Komnenos, 1143–1180, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30571-3

- Nicolle, David (2003), The First Crusade 1096–99: Conquest of the Holy Land, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-8417-6515-5

- Treadgold, Warren (1997), A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2630-2