Battle of Narva (1944)

The Battle of Narva[nb 1] was a military campaign between the German Army Detachment "Narwa" and the Soviet Leningrad Front fought for possession of the strategically important Narva Isthmus on 2 February – 10 August 1944 during World War II.

| Battle of Narva | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

Soldiers defending the Estonian bank of the Narva River, with the fortress of Ivangorod on the opposite side | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

123,541 personnel[1] 32 tanks[2] 137 aircraft[1] |

200,000 personnel[2][3] 2500 guns 125 tanks[4] 800 aircraft[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

14,000 dead or missing 54,000 wounded or sick 68,000 casualties[5] |

100,000 dead or missing 380,000 wounded or sick[nb 1] 300 tanks 230 aircraft[2] 480,000 casualties[5] | ||||||

| |||||||

The campaign took place in the northern section of the Eastern Front and consisted of two major phases: the Battle for Narva Bridgehead (February to July 1944)[6] and the Battle of Tannenberg Line (July–August 1944).[7] The Soviet Kingisepp–Gdov Offensive and Narva Offensives (15–28 February, 1–4 March and 18–24 March) were part of the Red Army Winter Spring Campaign of 1944.[8] Following Joseph Stalin's "Broad Front" strategy, these battles coincided with the Dnieper–Carpathian Offensive (December 1943 – April 1944) and the Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive (July–August 1944).[8] A number of foreign volunteers and local Estonian conscripts participated in the battle as part of the German forces. By giving its support to the illegal German conscription call, the underground National Committee of the Republic of Estonia had hoped to recreate a national army and restore the independence of the country.[9]

As a continuation of the Leningrad–Novgorod Offensive of January 1944, the Soviet Estonian operation pushed the front westward to the Narva River, aiming to destroy "Narwa" and to thrust deep into Estonia. The Soviet units established a number of bridgeheads on the western bank of the river in February while the Germans maintained a bridgehead on the eastern bank. Subsequent attempts failed to expand their toehold. German counterattacks annihilated the bridgeheads to the north of Narva and reduced the bridgehead south of the town, stabilizing the front until July 1944. The Soviet Narva Offensive (July 1944) led to the capture of the city after the German troops retreated to their prepared Tannenberg Defence Line in the Sinimäed Hills 16 kilometres from Narva. In the ensuing Battle of Tannenberg Line, the German army group held its ground. Stalin's main strategic goal—a quick recovery of Estonia as a base for air and seaborne attacks against Finland and an invasion of East Prussia—was not achieved. As a result of the tough defence of the German forces the Soviet war effort in the Baltic Sea region was hampered for seven and a half months.[10]

Background

Terrain

Terrain played a significant role in operations around Narva. The elevation above sea level rarely rises above 100 meters in the area and the land is cut by numerous waterways, including the Narva and Plyussa Rivers. The bulk of the land in the region is forested and large swamps inundate areas of low elevation. The effect of the terrain on operations was one of channelization; because of the swamps, only certain areas were suitable for large-scale troop movement.[1]

On a strategic scale, a natural choke point was present between the northern shore of Lake Peipus and the Gulf of Finland. The 45-kilometre wide strip of land was entirely bisected by the Narva River and had large areas of wilderness. The primary transportation routes, the Narva–Tallinn highway and railway, ran on an east-west axis near and parallel to the coastline. There were no other east-west transportation routes capable of sustaining troop movement on a large scale in the region.[1]

Preceding actions

On 14 January 1944, the Leningrad Front launched the Krasnoye Selo–Ropsha Offensive, aimed at forcing the German 18th Army back from its positions near Oranienbaum. On the third day of the offensive, the Soviets broke through German lines and pushed westward.[11] The Army Group North evacuated the civilian population of Narva.[12]

Soviet aims

By 1944 it was fairly routine practice for Stavka to assign its operating fronts new and more ambitious missions while the Soviet Armed Forces were conducting major offensive operations. The rationale was that relentless pressure might trigger a German collapse. For the 1943/1944 winter campaign, Stalin ordered the Red Army to conduct major offensives along the entire Soviet-German front in a continuation of the 'Broad Front' strategy he had pursued since the beginning of the war. This was applied in consonance with his long-standing rationale that, if the Red Army applied pressure along the entire front, German defences were likely to break in at least one section. The Soviet winter campaign included major assaults across the entire expanse the front in the Ukraine, Belorussia and against the German Panther Line in the region of the Baltic Sea.[8]

Breaking through the Narva Isthmus situated between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Peipus was of major strategic importance to the Soviet Armed Forces. The success of the Estonian operation would have provided an unobstructed lane to advance along the coast to Tallinn, forcing the German Army Group North to escape from Estonia for fear of getting cornered. For the Baltic Fleet trapped in an eastern bay of the Gulf of Finland, Tallinn was the closest exit to the Baltic Sea.[1] The ejection of the Army Group North from Estonia would have made Finland subject to air and amphibious attacks originating from Estonian bases. The prospect of an invasion of East Prussia through Estonia[13] appealed even more to Stavka, as it could bring German resistance to a standstill.[14] With the participation of Leonid Govorov, commander of the Leningrad Front, and Vladimir Tributz, commander of the Baltic Fleet, a scheme was prepared to destroy the Army Group North.[14][15] Stalin ordered the capture of Narva at all costs no later than 17 February:[16]

- "It is mandatory that our forces seize Narva no later than 17 February 1944. This is required both for military as well as political reasons. It is the most important thing right now. I demand that you undertake all necessary measures to liberate Narva no later than the period indicated. (signed) I. Stalin"

After the failure of the Leningrad Front, Stalin gave a new order on 22 February: to break through the "Narwa" defence, give a shock at Pärnu, eliminate the German forces in Estonia, direct two armies at Southeast Estonia, keep going through Latvia and open the road to East Prussia and Central Europe. On the same day, the Soviet Union presented Finland with peace conditions.[16] While Finland regarded the terms as unacceptable, the war waging around them appeared dangerous enough to keep negotiating. To influence Finland, Stalin needed to take Estonia.[13] His wish was an order to the commanders of the Leningrad Front, with their heads at stake.[10] After reinforcements, the Narva front acquired the highest concentration of forces at any point on the Eastern Front in March 1944.[17]

Soviet deployments

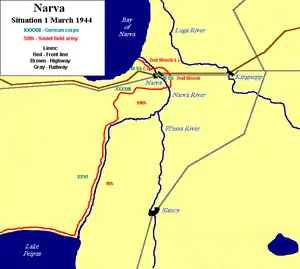

Three Soviet armies were deployed at the maximum concentration of forces in March 1944. The 2nd Shock Army was placed north of Narva, the 59th Army was positioned south of Narva and the 8th Army south of the 59th Army along the 50 km long Narva River stretching down to Lake Peipus. Detailed information on the size of the Soviet forces at the Narva front during the Winter-Spring campaign has not been published by any sources. It is impossible to give an overview on the Soviet strength until the Red Army archival information is made available to non-Russian investigators or published.[1] Estonian historian Hannes Walter has estimated the number of Soviet troops in the Battle of Narva at 205,000,[3] which is in accordance with the number of divisions multiplied by the assumed sizes of the divisions presented by the Estonian historian Mart Laar.[2] The order of battle of the Leningrad Front as of 1 March 1944:[18]

- 2nd Shock Army – Lieutenant General Ivan Fedyuninsky

- 43rd Rifle Corps – Major General Anatoli Andreyev

- 109th Rifle Corps – Major General Ivan Alferov

- 124th Rifle Corps – Major General Voldemar Damberg

- 8th Army – Lieutenant General Filip Starikov

- 6th Rifle Corps – Major General Semyon Mikulski

- 112th Rifle Corps – Major General Filip Solovev

- 59th Army – Lieutenant General Ivan Korovnikov

- 117th Rifle Corps – Major General Vasili Trubachev

- 122nd Rifle Corps – Major General Panteleimon Zaitsev

Separate detachments:

- 8th Estonian Rifle Corps – Lieutenant General Lembit Pärn[19]

- 14th Rifle Corps – Major General Pavel Artyushenko

- 124th Rifle Division – Colonel Mikhail Papchenko

- 30th Guards Rifle Corps – Lieutenant General Nikolai Simonyak

- 46th, 260th and 261st Separate Guards Heavy Tank and 1902nd Separate Self-propelled Artillery regiments[20]

- 3rd Breakthrough Artillery Corps – Major General N. N. Zhdanov

- 3rd Guards Tank Corps – Major General I. A. Vovchenko

At the start of the Narva Offensive (July 1944), the Leningrad Front deployed 136,830 troops,[21] 150 tanks, 2,500 assault guns and 800+ aircraft.[2]

German and Finnish aims

The Oberkommando des Heeres believed it was crucial to stabilize the front on the Narva River. A Soviet breakthrough here would have meant the loss of the northern coast of Estonia and with it loss of control of the Gulf of Finland, giving the Soviet Baltic Fleet access to the Baltic Sea.[1] A breakthrough by the fleet would have threatened German control of the entire Baltic Sea and the shipment of iron ore imports from Sweden. The loss of Narva would have meant fuel derived from the adjacent Kohtla-Järve oil shale deposits (32 kilometers west of Narva on the coast) would be denied to the German war machine.[1] As Colonel General Georg Lindemann said in his daily order to the 11th Infantry Division:[22]

We are standing on the border of our native land. Every step backwards will carry the war through the air and water to Germany.

As Finland was negotiating with the Soviet Union for peace, the Oberkommando des Heeres paid attention to the Narva front, using every means to convince the Finnish Defence Command that their defence was going to hold. The German command informed their Finnish colleagues in detail about the events on the Narva front while a delegation of the Finnish Defence Command visited Narva in spring 1944.[2] Besides being a narrow corridor well suited for defence, the terrain in the area of Narva was dominated by forests and swamps. Directly behind the Narva River lay the city itself, ideally positioned as a bastion from which defending forces could influence combat to both the north and south of the city along the river valley.[1]

This position was the northern segment of the German Panther Line and it was where Generalfeldmarschall Georg von Küchler in charge of the Army Group wanted to set up his defence. Hitler initially refused and replaced von Küchler with Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model as the commander of the Army Group North.[11] Model agreed with von Küchler, and as one of Hitler's favourites he also was allowed more freedom. Using this freedom to his advantage, Model managed to fall back and begin establishing a line along the Narva River with a strong bridgehead on the eastern bank in Ivangorod. This appeased Hitler and followed the German standard operating procedure for defending a river line.[11] On 1 February 1944, the High Command of Army Group North tasked the Sponheimer Group (renamed Army Detachment "Narwa" on 23 February) to defend the segment of the Panther Line at the isthmus between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Peipus at all costs.[1] Stalin presented Finland with his peace terms on 8 February 1944, after the initial Soviet success. With the tactical victories of "Narwa" from mid-February to April, Finland terminated the negotiations on 18 April 1944.[23][2]

Aims of the Estonian resistance movement

During the course of the occupation of Estonia by Nazi Germany, Estonian expectations of regaining their independence began to diminish. Pursuant to the Constitution of Estonia, formally still in force, Estonian politicians formed an underground National Committee of the Republic of Estonia which convened on 14 February 1944. As President Konstantin Päts was currently imprisoned by the Soviet authorities, the acting head of state according to the Constitution was the former Prime Minister Jüri Uluots. The German-appointed Estonian Self-Administration had previously attempted several unsuccessful general mobilisation calls, which were illegal under the Hague Conventions (1899 and 1907) and opposed by Uluots.[24][25] In February 1944 when the Leningrad Front reached the vicinity of Narva and the Soviet return became a real threat, Uluots switched his stand on the German draft. In a radio speech on 7 February, Uluots reasoned that armed Estonians could become useful against both Germans and Soviets. He also hinted that Estonian troops on Estonian soil would have: "... a significance much wider than what I could and would be able to disclose here."[26] Along with other Estonian politicians, Uluots saw resistance against the Soviet Armed Forces as a means of preventing the restoration of Soviet power and restoring Estonia's independence once the war was over.[27] The conscription call was received with popular support and the mobilisation brought together 38,000 men[28] who were formed into seven border guard regiments and the fictitiously named[12] 20th Estonian SS-Volunteer Division,[29][30] commonly referred to among the German Armed Forces as the Estonian Division.[10] Combined with the Finnish Infantry Regiment 200 (voluntary Estonians in the Finnish army) and the conscripts within the Waffen SS, a total of 70,000 Estonian troops were under Nazi German arms in 1944.[24]

Formation of Army Detachment "Narwa"

In February 1944, the L and LIV Army Corps along with the III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps were on the left flank of the 18th Army as they retreated to Narva. On 4 February, the Sponheimer Group was released from the 18th Army and subordinated directly to the Army Group North. In support of the forces already in place, Hitler ordered reinforcements. The Panzer-Grenadier-Division Feldherrnhalle, with over 10,000 troops and their equipment, was airlifted from Belorussia into Estonia via the airfield at Tartu on 1 February. A week later, the 5th Battalion of the Panzergrenadier Großdeutschland Division arrived at the front. The Grenadier Regiment Gnesen (an ad hoc regiment formed from replacement army units in Poland) was sent from Germany and arrived on 11 February. Three days later, the 214th Infantry Division was transferred from Norway. Over the next two weeks various units were added to the group, including the 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division "Nordland", several divisions of the Wehrmacht, the Estonian Division and local Estonian border guard and Estonian Auxiliary Police battalions. Infantry General Otto Sponheimer was replaced by General Johannes Frießner and the Sponheimer Group was renamed Army Detachment "Narwa" on 23 February. The Army Group North ordered the deployment of "Narwa" on 22 February in the following positions: III SS Panzer Corps deployed to Narva, Ivangorod Bridgehead on the east bank of the river and north of Narva; the XXXXIII Army Corps against the Krivasoo Bridgehead south of the city; and the XXVI Army Corps to the sector between the Krivasoo Bridgehead and Lake Peipus. As of 1 March 1944, there were a total of 123,541 personnel subordinated to the Army Group in the following order of battle:[1]

- III SS (Germanic) Panzer Corps – SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner

- XXVI Army Corps – General Anton Grasser

- 11th Infantry Division

- 58th Infantry Division

- 214th Infantry Division

- 225th Infantry Division (Wehrmacht)

- 3rd Estonian Border Guard Regiment (as of 15 April)

- XXXXIII Army Corps – General der Infanterie Karl von Oven

- 61st Infantry Division

- 170th Infantry Division

- 227th Infantry Division

- Feldherrnhalle Panzergrenadier Division

- Gnesen Grenadier Regiment

Separate units:

- Eastern sector, coastal defence (the staff of the 2nd Anti-Aircraft Division as the HQ) – Lieutenant General Alfons Luczny

- Estonian Regiment "Reval"

- 3 Estonian police battalions

- 2 Estonian eastern battalions

Other military units:

- Artillery Command No. 113

- High Pioneer Command No. 32

- 502nd Heavy Tank Battalion

- 752nd Anti-Tank Battalion

- 540th Special Infantry (Training) Battalion

In the summer of 1944, the Panzergrenadier Division Feldherrnhalle and seven infantry divisions were removed from the Narva Front,[2] leaving 22,250 troops at the location.[31]

Combat activity

Formation of bridgeheads

Launching the Kingisepp–Gdov Offensive on 1 February, the Soviet 2nd Shock Army's 109th Rifle Corps captured the town of Kingisepp on the first day.[16] The German 18th Army was forced into new positions on the eastern bank of the Narva River.[1] Forward units of the 2nd Shock Army crossed the river and established several bridgeheads on the west bank to the north and south of the city of Narva on 2 February. The 2nd Shock Army expanded the bridgehead in the Krivasoo Swamp south of Narva five days later, temporarily cutting the Narva–Tallinn Railway behind the III SS Panzer Corps. Govorov was unable to encircle the smaller German Army Group, which called in reinforcements. These came mostly from the newly mobilised Estonians, motivated to resist the looming Soviet return. At the same time, the Soviet 108th Rifle Corps landed units across Lake Peipus 120 kilometres south of Narva and established a bridgehead around the village of Meerapalu. By a coincidence, the I.Battalion, SS Volunteer Grenadier Regiment 45 (1st Estonian), which was headed for Narva, reached the same area. A battalion of the 44th Infantry Regiment (consisting of personnel from East Prussia), the I.Battalion, 1st Estonian and an air squadron destroyed the Soviet bridgehead on 15–16 February. The Mereküla Landing Operation was conducted as the 517-strong 260th Independent Naval Infantry Brigade landed at the coastal borough of Mereküla behind the Sponheimer Group lines. However, the unit was almost completely destroyed.[1][10]

Narva Offensives, 15–28 February and 1–4 March

The Soviet 30th Guards Rifle Corps and the 124th Rifle Corps launched a new Narva Offensive on 15 February.[8] The resistance by units of the Sponheimer Group exhausted the Soviet army, which halted its offensive. Both sides used the pause for bringing in additional forces. The fresh SS Volunteer Grenadier Regiments 45 and 46 (1st and 2nd Estonian) accompanied by units of the "Nordland" Division destroyed the Soviet bridgeheads north of Narva by 6 March. The newly arrived 59th Army attacked westwards from the Krivasoo Swamp and encircled the strong points of the 214th Infantry Division and Estonian 658th and 659th Eastern Battalions. The resistance of the encircled units gave the German command time to move in all available forces and to stop the 59th Army units' advance.[1][10]

6–24 March

The Soviet air force conducted an air raid, leveling the historic town of Narva on 6 March. An air and artillery shock of 100,000 shells and grenades at the "Nordland" and "Nederland" detachments in Ivangorod prepared the way for the 30th Guards Rifle Division's attack on 8 March. Simultaneous pitched battles took place north of the town, where the 14th Rifle Corps supported by the artillery of the 8th Estonian Rifle Corps attempted to re-establish a bridgehead. Regiments of the Estonian SS Division repulsed the attacks, causing great Soviet losses.[1][10]

Soviet air assaults against civilians in Estonian towns were a part of the offensive, aimed at forcing the Estonians away from supporting the German side. The Soviet Long Range Aviation branch assaulted the Estonian capital of Tallinn on the night of 8–9 March. Approximately 40% of the housing was destroyed in the city; 25,000 people were left homeless and 500 civilians were killed. The result of the air raid was the opposite of what the Soviets intended, as people felt disgusted by the Soviet atrocities; more men answered the German conscription call.[1][10]

The Soviet tank attack at Auvere Station was stopped by a squadron of the 502nd Heavy Tank Battalion on 17 March. The ensuing offensive continued for another week[8] until the Soviet forces had suffered enough casualties to switch over to a defensive stance. This enabled "Narwa" to take the initiative.[1][10]

Strachwitz offensive

The Strachwitz Battle Group annihilated the Soviet 8th Army shock troop wedge at the western end of the Krivasoo Bridgehead on 26 March. The German battle group destroyed the eastern tip of the bridgehead on 6 April. Generalmajor Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz von Groß-Zauche und Camminetz, inspired by the success, tried to eliminate the whole bridgehead but was unable to proceed due to the spring thaw that had rendered the swamp impassable for the Tiger I tanks.[32] By the end of April, the parties had mutually exhausted their strengths. Relative calm settled on the front until late July 1944.[1][10]

The Soviets capture Narva

The Soviet breakthrough in Belorussia and Karelian Offensive forced the Army Group North to withdraw a large portion of their troops from Narva to the central part of the Eastern Front and to Finland. As there were insufficient forces for the defence of the former front line at Narva in July, the German army detachment began preparations for withdrawal to the Tannenberg defence line in the Sinimäed Hills 16 kilometres from Narva. The commanders of the Leningrad Front were unaware of the preparations; they designed a new Narva Offensive. Shock troops from the Finnish front were concentrated near the town, giving the Leningrad Front a 4:1 superiority both in manpower and equipment. Before the German forces had implemented their plan, the Soviet 8th Army launched their offensive; the Battle of Auvere was the result. The I.Battalion, 1st Estonian and the 44th Infantry Regiment repulsed the attack, inflicting heavy losses on the 8th Army. The "Nordland" and "Nederland" detachments in Ivangorod left their positions quietly during the night before 25 July. The evacuation was carried out according to the German plans until the 2nd Shock Army resumed the offensive in the morning. Supported by 280,000 shells and grenades from 1360 assault guns, the army crossed the river north of the town. The II.Battalion, 1st Estonian Regiment kept the Soviet shock Army from capturing the highway behind the retreating troops. The defensive operation led to the destruction of the SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Regiment 48 "General Seyffardt" due to tactical errors. The Soviet forces captured Narva on 26 July.[1][10]

Tannenberg Line

The Soviet vanguard 201st and 256th Rifle Divisions attacked the Tannenberg Line and captured part of the Orphanage Hill, the easternmost of the area. The Anti-Tank Company, SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 24 "Danmark" returned the hill to the hands of the "Narwa" the following night. The III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps repulsed subsequent Soviet attempts to capture the hills by tanks on the following day. The SS Reconnaissance Battalion 11 and the I.Battalion, Waffen Grenadier Regiment 47 (3rd Estonian) launched a counterattack during the night before 28 July. The assault collapsed under the Soviet tank fire which destroyed the Estonian battalion. In a pitched battle carried over to the next day without a break in the fighting, the two Soviet armies forced "Narwa" into new positions at the Grenadier Hill, the central one.[1][10]

The climax of the Battle of Tannenberg Line was the Soviet attack of 29 July. The shock units suppressed the German resistance on the Orphanage Hill, while the Soviet main forces suffered heavy casualties in the subsequent assault at the Grenadier Hill. The Soviet tanks encircled it and the Tower Hill, the westernmost one. Steiner, the commander of the III SS Panzer Corps, sent out the remaining seven tanks, which hit the surprised Soviet armour and forced them back. This enabled an improvised battle group led by Hauptsturmführer Paul Maitla to launch a counterattack which recaptured the Grenadier Hill. Of the 136,830 Soviets initiating the offensive on 25 July, a few thousand had remained fit for combat by 1 August. The Soviet tank regiments had been demolished.[1][10]

With swift reinforcements, the two Soviet armies continued their attacks. The Stavka demanded the destruction of the "Narwa" and the capture of Rakvere by 7 August. The 2nd Shock Army was back to 20,000 troops by 2 August while numerous attempts using unchanged tactics failed to break the multinational defence of the "Narwa". Leonid Govorov, the commander of the Leningrad Front terminated the offensive on 10 August.[1][10]

Casualties

During the Soviet era, the losses in the battle of Narva were not released by the Soviets.[2] In recent years, Russian authors have published some figures[14][33] but not for the whole course of the battles.[2] The number of Soviet casualties can only be estimated indirectly.[1][2]

The Army Detachment "Narwa" lost 23,963 personnel as dead, wounded and missing in action in February 1944.[31] During the following months through to 30 July 1944, an additional 34,159 German personnel were lost, 5,748 of them dead and 1,179 missing in action.[1] The total German casualties during the initial phase of the campaign was approximately 58,000 men, 12,000 of them dead or missing in action. From 24 July to 10 August 1944, the German forces buried 1709 men in Estonia.[2][34] Adding the troops missing in action, the number of dead in the period is estimated at approximately 2,500. Accounting the standard ratio of 1/4 of the wounded as irrecoverable losses, the number of German casualties in the later period of the battle was approximately 10,000. The total German casualties during the Battle of Narva is estimated at 14,000 dead or missing and 54,000 wounded or sick.[2]

Aftermath

Baltic Offensive

On 1 September, Finland announced the cessation of military cooperation with Germany to sign an armistice with the Soviet Union.[23] On 4 September, Finland opened access for the Soviets to Finnish waters. With the Soviet offensive at Riga threatening to complete their encirclement, the Army Group North started preparations for the withdrawal of troops from Estonia in an operation codenamed Aster. The possible transportation corridors were thoroughly prepared using maps at headquarters.[2][35] On 17 September 1944, a naval force under Vice-Admiral Theodor Burchardi began evacuating elements of the German formations and Estonian civilians. Within six days, around 50,000 troops and 1,000 prisoners had been removed.[36] The elements of the 18th Army in Estonia were ordered to withdraw into Latvia.

The Soviet 1st, 2nd and 3rd Baltic Fronts launched their Baltic Offensive on 14 September. The operation was aimed at cutting off the Army Group North in Estonia. After much argument, Adolf Hitler agreed to allow the total evacuation of the troops in mainland Estonia. The 2nd Shock Army launched its Tallinn Offensive on 17 September from the Emajõgi River Front in South Estonia. At midnight on 18 September, the Army Detachment "Narwa" left its positions in the Tannenberg Line. The 8th Army reconnaissance reported the evacuation five hours after it had been completed and the Soviets started to chase the troops towards Estonian harbours and the Latvian border. The III SS Panzer Corps reached Pärnu by 20 September, while the II SS Corps retreated southwards to form the 18th Army's rearguard.[36] The Soviet armies advanced to take Tallinn on 22 September. The Soviets had demolished the harbour at Haapsalu by 24 September. The German Panzer Corps evacuated Vormsi Island just off the coast on the following day, successfully completing the evacuation of mainland Estonia with only minor casualties.[1] The 8th Army went on to take the remaining West Estonian archipelago in the Moonsund Landing Operation. The Baltic Offensive resulted in the expulsion of the German forces from Estonia, a large part of Latvia, and Lithuania.

During the withdrawal from Estonia, the German command released thousands of native Estonian conscripts from military service. The Soviet command began conscripting Baltic natives as areas were brought under Soviet control.[38] While some ended up serving on both sides, thousands joined the Forest Brothers partisan detachments to avoid conscription.

Army Group North land lines of communication were permanently severed from Army Group Centre and it was relegated to the Courland Pocket, an occupied Baltic seashore area in Latvia. On 25 January, Adolf Hitler renamed Army Group North the "Courland", implicitly realising that there was no possibility of restoring a new land corridor between Courland and East Prussia.[39] The Red Army commenced the encirclement and reduction of the pocket, enabling the Soviets to focus on operations towards East Prussia. The Army Group Courland retained a possibility of being a major threat. Operations by the Red Army against the Courland Pocket continued until the surrender of Army Group Courland on 9 May 1945, when close to 200,000 Germans were taken prisoner there.

Outcome for Finland

The lengthy German defence during the Battle of Narva denied the Soviets the use of Estonia as a favorable base for amphibious invasions and air attacks against Helsinki and other Finnish cities. Stavka's hopes of assaulting Finland from Estonia and forcing it into capitulation were diminished. Finnish Chief of Defence Carl Gustav Emil Mannerheim repeatedly reminded the German side that in the event their troops in Estonia retreated, Finland would be forced to make peace even on extremely unfavourable terms. Thus, the prolonged Battle of Narva helped Finland avoid a Soviet occupation, sustained its capacity for resistance and enabled them to enter negotiations for the Moscow Armistice on their own terms.[4][14][16][10][31]

Attempt to restore Estonian Government

The lengthy German defence prevented a swift Soviet breakthrough into Estonia and gave the underground National Committee of the Republic of Estonia enough time to attempt to re-establish Estonian independence. On 1 August 1944, the national committee pronounced itself Estonia's highest authority and on 18 September 1944, acting head of state Uluots appointed a new government led by Otto Tief. Over the radio in English, the government declared its neutrality in the war. The government issued two editions of the Riigi Teataja (State Gazette) but did not have time to distribute them. On 21 September, the national forces seized the government buildings in Toompea, Tallinn and ordered the German forces to leave.[40][41] The flag of Estonia was hoisted at the tower of Pikk Hermann, to be removed by the Soviets four days later. The Estonian Government in Exile served to carry the continuity of the Estonian state forward until 1992, when it handed its credentials over to the incoming President, Lennart Meri.

Civilian refugees

The delay of the Soviet advance allowed over 25,000 Estonians and 3,700 Swedes to flee to neutral Sweden and 6,000 Estonians to Finland. Thousands of refugees died on boats and ships sunk in the Baltic Sea.[24] In September, 90,000 soldiers and 85,000 Estonian, Finnish and German refugees and Soviet prisoners of war were evacuated to Germany. The sole German cost of this evacuation was the loss of a steamboat. More German naval evacuations followed from Estonian ports, where up to 1,200 people were drowned in Soviet attacks.[24]

Soviet reoccupation

Soviet rule of Estonia was re-established by force, and sovietisation followed, mostly carried out in 1944–1950. The forced collectivisation of agriculture began in 1947 and was completed after the deportation of 22,500 Estonians in March 1949. All private farms were confiscated and farmers were made to join the collective farms. Besides the armed resistance of the Forest Brothers, a number of underground nationalist schoolchildren groups were active. Most of their members were sentenced to long terms of imprisonment. The punitive actions decreased rapidly after Stalin's death in 1953; from 1956 to 1958, many of the deportees and political prisoners were allowed to return to Estonia. Political arrests and numerous other crimes against humanity were committed throughout the occupation period until the late 1980s. Nevertheless, the attempt to integrate Estonian society into the Soviet system failed. Although the armed resistance was defeated, the population remained anti-Soviet. This helped the Estonians to organise a new resistance movement in the late 1980s, regain their independence in 1991, and then rapidly develop a modern society.[42]

References and notes

Footnotes

- Estonian: Narva lahing; German: Schlacht bei Narva; Russian: Битва за Нарву

References

- Toomas Hiio (2006). "Combat in Estonia in 1944". In Toomas Hiio; Meelis Maripuu; Indrek Paavle (eds.). Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 1035–1094.

- Mart Laar (2006). Sinimäed 1944: II maailmasõja lahingud Kirde-Eestis (Sinimäed Hills 1944: Battles of World War II in Northeast Estonia) (in Estonian). Tallinn: Varrak.

- Hannes Walter. "Estonia in World War II". Mississippi: Historical Text Archive. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- F.I.Paulman (1980). "Nachalo osvobozhdeniya Sovetskoy Estoniy". Ot Narvy do Syrve (From Narva to Sõrve) (in Russian). Tallinn: Eesti Raamat. pp. 7–119.

- Doyle, Peter (2013). World War II in Numbers. A & C Black. p. 105. ISBN 9781408188194.

- McTaggart, Pat (2003). "The Battle of Narva, 1944". In Command Magazine (ed.). Hitler's army: the evolution and structure of German forces. Cambridge, MA: Combined Books. pp. 294, 296, 297, 299, 302, 305, 307.

- McTaggart, Pat (2003). "The Battle of Narva, 1944". In Command Magazine (ed.). Hitler's army: the evolution and structure of German forces. Cambridge, MA: Combined Books. p. 306.

- David M. Glantz (2001). The Soviet-German War 1941–1945: Myths and Realities. Glemson, South Carolina: Strom Thurmond Institute of Government and Public Affairs, Clemson University.

- Romuald J. Misiunas, Rein Taagepera The Baltic States, Years of Dependence, 1940–1980. p. 66. University of California Press, 1983

- Laar, Mart (2005). "Battles in Estonia in 1944". Estonia in World War II. Tallinn: Grenader. pp. 32–59.

- Kenneth W. Estes. A European Anabasis – Western European Volunteers in the German Army and SS, 1940–1945. Chapter 5. "Despair and Fanaticism, 1944–45" Columbia University Press

- Robert Sturdevant (10 February 1944). "Strange Guerilla Army Hampers Nazi Defence of Baltic". Times Daily. Florence, Alabama.

- Евгений Кривошеев; Николай Костин (1984). "I. Sraženie dlinoj v polgoda (Half a year of combat)". Битва за Нарву, февраль-сентябрь 1944 год (The Battle for Narva, February–September 1944) (in Russian). Tallinn: Eesti raamat. pp. 9–87.

- В.Бешанов (2004). Десять сталинских ударов (Ten Shocks of Stalin). Харвест, Minsk.

- Иван Иванович Федюнинский (1961). Поднятые по тревоге (Risen by Agitation) (in Russian). Воениздат, Moscow.

- David M. Glantz (2002). The Battle for Leningrad: 1941–1944. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1208-4.

- L. Lentsman (1977). Eesti rahvas Suures Isamaasõjas (Estonian People in Great Patriotic War) (in Estonian). Tallinn: Eesti Raamat.

- Боевой состав Советской Армии на 1 марта 1944 г. Archived 14 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (Order of battle of the Soviet Army on 1 March 1944)

- 8th & 14th Rifle Corps may have been under the 42nd Army, but the source above does not list it as such.

- Операция "Нева-2" http://www.rkka.ru/memory/baranov/6.htm chapter 6, Baranov, V.I., Armour and people, from a collection "Tankers in the combat for Leningrad"Lenizdat, 1987 (Баранов Виктор Ильич, Броня и люди, из сборника "Танкисты в сражении за Ленинград". Лениздат, 1987)

- G.F.Krivosheev (1997). Soviet casualties and combat losses in the twentieth century. London: Greenhill Books.

- Gruppen-Befehl für den Küstenschutz. (Detachment Orders to the Coastal Defence. In German). 9 February 1944. Berlin Archives MA RH24-54/122

- Toomas Hiio; Meelis Maripuu; Indrek Paavle, eds. (2006). "Chronology of events in 1939–1945". Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 1191–1237.

- Estonian State Commission on Examination of Policies of Repression (2005). "Human Losses". The White Book: Losses inflicted on the Estonian nation by occupation regimes. 1940–1991 (PDF). Estonian Encyclopedia Publishers. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2013.

- Lauri Mälksoo (2006). "The Government of Otto Tief and Attempt to Restore the Independence of Estonia in 1944: A Legal Appraisal.". Toomas Hiio, Meelis Maripuu, Indrek Paavle (Eds.). Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 1095–1106.

- Taagepera pp. 70

- "Year 1944 in Estonian History". Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009.

- Lande, D. A. (2000). Resistance!: Occupied Europe and Its Defiance of Hitler. MBI. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7603-0745-8.

- "20. Waffen-Grenadier-Division der SS (estnische Nr. 1)". Axis History Factbook.

- Toomas Hiio & Peeter Kaasik (2006). "Estonian units in the Waffen-SS". In Toomas Hiio; Meelis Maripuu & Indrek Paavle (eds.). Estonia 1940–1945: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity. Tallinn. pp. 927–968.

- Steven H. Newton (1995). Retreat from Leningrad: Army Group North, 1944/1945. Atglen, Philadelphia: Schiffer Books. ISBN 0-88740-806-0.

- Otto Carius (2004). Tigers in the Mud: The Combat Career of German Panzer Commander Otto Carius. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2911-7.

- V. Rodin (5 October 2005). "Na vysotah Sinimyae: kak eto bylo na samom dele. (On the Heights of Sinimäed: How It Actually Was)" (in Russian). Vesti. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Unpublished data by the German War Graves Commission

- Felix Steiner (1980). Die Freiwilligen der Waffen-SS: Idee und Opfergang (Volunteers of Armed SS. In German). Schütz, Oldendorf, Preuss

- Mitcham, S. German Defeat in the East 1944 – 45, Stackpole, 2007, p.149

- D. Muriyev, Preparations, Conduct of 1944 Baltic Operation Described, Military History Journal (USSR Report, Military affairs), 1984–9, page. 27

- On 25 January, Hitler renamed three army groups: the North became the Courland; the Centre became the North and the A became Army Group Centre

- "The Otto Tief government and the fall of Tallinn". Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2006. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009.

- Estonia. Sept.21 Bulletin of International News by Royal Institute of International Affairs Information Dept.

- "Phase III: The Soviet Occupation of Estonia from 1944". In: Estonia since 1944: Reports of the Estonian International Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Against Humanity, pp. VII–XXVI. Tallinn, 2009

Further reading

- McTaggart, Pat (2003). "The Battle of Narva, 1944". In Command Magazine (ed.). Hitler's Army: the evolution and structure of German forces. Cambridge, MA: Combined Books. pp. 287–308. ISBN 978-0306812606.

- Miljan, Toivo (2004). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4904-4.