Battle of Ohaeawai

The Battle of Ohaeawai was fought between British forces and local Māori during the Flagstaff War in July 1845 at Ohaeawai[1] in the North Island of New Zealand. Te Ruki Kawiti, a prominent rangatira (chief) was the leader of the Māori forces.[4] The battle was notable in that it established that the fortified pā could withstand bombardment from cannon fire and that frontal assaults by soldiers would result in serious troop losses.

| Battle of Ohaeawai | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Flagstaff War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Māori | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Lieutenant Colonel Henry Despard: 58th Regiment ~ 10 officers and 200 men;[1][2] 96th Regiment - 'a company';[3] 99th Regiment ~ 7 officers and 150 men;[1][2] Tāmati Wāka Nene ~ 400 warriors HMS Hazard ~ 10 officers and men[1] Auckland Volunteer Militia ~ 30 men[1] |

Te Ruki Kawiti ~ 150 warriors Pene Taui ~ 150 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 33 dead, 66 wounded | light | ||||||

Kawiti's success at Ohaeawai Pā

After the Battle of Te Ahuahu a debate occurred between Te Ruki Kawiti and the Ngatirangi chief Pene Taui as to the site of the next battle; Kawiti eventually agreed to the request to fortify Pene Taui's Pā at Ohaeawai.[5] In the winter months of 1845 Lieutenant Colonel Despard led a combined force of troops from the 58th, 96th, and 99th Regiments, Royal Marines and Māori allies in an attack on Pene Taui's Pā at Ohaeawai,[6] which had been fortified by Kawiti.

The British troops arrived before the Ohaeawai Pā on 23 June and established a camp about 500 metres (1,600 ft) away. On the summit of a nearby hill (Puketapu) they built a four-gun battery. They opened fire next day and continued until dark but did very little damage to the palisade. The next day the guns were brought to within 200 metres (660 ft) of the pā. The bombardment continued for another two days but still did very little damage. Partly this was due to the elasticity of the flax covering the palisade.[7] Since the introduction of muskets the Māori had learnt to cover the outside of the palisades with layers of flax (Phormium tenax) leaves, making them effectively bulletproof as the velocity of musket balls was dissipated by the flax leaves.[7] However the main fault was a failure to concentrate the cannon fire on one area of the defences, so as to create a breach in the palisade.[7]

In English, it translates as, “This is a sacred memorial to the soldiers and sailors of the Queen who fell in battle here at Ohaeawai in the year of Our Lord 1845. This burying place was laid out by the Maoris after the making of peace.”

After two days of bombardment without effecting a breach, Despard ordered a frontal assault. He was, with difficulty, persuaded to postpone this pending the arrival of a 32-pound naval gun which came the next day, 1 July. However an unexpected sortie from the pā resulted in the temporary occupation of the knoll on which Tāmati Wāka Nene had his camp and the capture of Nene's colours—the Union Jack. The Union Jack was carried into the pā. There it was hoisted, upside down, and at half-mast high, below the Māori flag, which was a Kākahu (Māori cloak).[1] This insulting display of the Union Jack was the cause of the disaster which ensued.[5] Infuriated by the insult to the Union Jack, Colonel Despard ordered an assault upon the pā the same day. The attack was directed to the section of the pā where the angle of the palisade allowed a double flank from which the defenders of the pā could fire at the attackers; the attack was a reckless endeavour.[8] The British persisted in their attempts to storm the unbreached palisades and five to seven minutes later 33 were dead and 66 injured.[9] The casualties included Captain Grant of the 58th Regiment and Lieutenant Phillpotts of HMS Hazard.[10] The scalp of Lieutenant Phillpotts was brought to the tohunga Te Atua Wera, who made divinations and composed a song foretelling victory against the British.[11]

Shaken by the loss of a third of his troops, Despard decided to abandon the siege. However, his Māori allies contested this decision. Tāmati Wāka Nene persuaded Despard to wait for a few more days. More ammunition and supplies were brought in and the shelling continued. On the morning of 8 July the pā was found to have been abandoned, the occupants having disappeared in the night. When they had a chance to examine it the British officers found it to be even stronger than they had feared.[12]

The defenders of the pā had four iron cannons on ship-carriages including a carronade that was loaded with a bullock-chain, and fired at close quarters at the attacking soldiers. The colonial forces captured these cannons, one of which had been destroyed by a shot from a British cannon.[13]

The drawing by Mr Symonds of the 99th Regiment describes Ohaeawai's inner palisade as being 3 metres (9.8 ft) high, built using Puriri logs. In front of the inner palisade was a ditch in which the warriors could shelter and reload their muskets then fire through gaps in the two outer palisades.[14]

Relying on the report of her husband Henry who observed the battle, Marianne Williams commented on the ingenuity of the construction of the war pā:

It is quite astonishing how they seem to defy the British in their fortifications. They have double fences, ditches, and loop holes, their houses sunk underground; and as the great guns of the British are fired through their pa with so little loss to the rebels, it is supposed that they have large holes, in which they secure themselves. The fence round the pa is covered between every paling with loose bunches of flax, against which the bullets fall and drop; in the night they repair every hole made by the guns.[15]

The pā was duly destroyed and the British retreated once again to the Bay of Islands. Te Ruki Kawiti and his warriors escaped[12] and proceeded to construct an even stronger pā at Ruapekapeka. The Battle of Ohaeawai was presented as a victory for the British force, notwithstanding the death of about a third of the soldiers. The reality of the end of the Battle of Ohaeawai was that Kawiti and his warriors had abandoned the pā in a tactical withdrawal; with the Ngāpuhi moving on to build the Ruapekapeka Pā from which to engage the British force on a battle field chosen by Kawiti.

Hone Heke did not participate in the Battle of Ohaeawai as he was recovering from the wounds he received at the Battle of Te Ahuahu.

Model for the gunfighter pa

After the battle, models were made of the design of the pā, with one being sent to Britain where it sat forgotten in a museum. Other Māori tribes of New Zealand became aware of the techniques used in the design of the Ohaeawai Pā in order to blunt the effectiveness of cannon and musket fire and to create firing trenches located within the inner palisade and communication trenches linking to ruas—shelters dug into the ground and covered with earth.[16] The design of the Ohaeawai Pā, and the pā subsequently built by Kawiti at Ruapekapeka, became the basis of what is now called the gunfighter pā.[17][18][19]

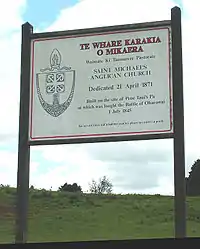

Site of the battle

While the place at which the battle was fought is now called, Ngawha, it was known as Ohaeawai at the time of the battle.[20] Cowan identifies that "the site of the Ohaeawai pa is now occupied by a Maori church and burying-ground. The scene of the battle is five miles from Kaikohe and two miles from the Township of Ohaeawai. A Maori church of old-fashioned design is seen on the left as one travels from Kaikohe; it stands on a gentle rise a short distance west of the main road. The locality is usually called Ngawha, from the hot springs in the neighbourhood, but it is the true Ohaeawai; the European township which has appropriated the name should properly be known as Taiamai. The church occupies the centre of the olden fortification, and a scoria-stone wall, 7 ft. high, encloses the sacred ground."[21]

The church was built on the site of the Ohaeawai pā in 1870.[10]

See also

References

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 8: The Storming-Party at Ohaeawai". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 60–72.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 9: The Capture of Rua-Pekapeka". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 73–87.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 7: The Attack on Ohaeawai". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. p. 50.

- Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at war, 1815-1914: an encyclopedia of British military history. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-925-6.

- Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). "Hekes War in the North". No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand. pp. 38–43. Retrieved 10 Oct 2012.

- Cowan, James (1955). "Ground Plan of Ohaeawai Pā". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). Retrieved 10 Oct 2012.

- Cowan, James (1955). "Flax-masked Palisade". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). Retrieved 10 Oct 2012.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 112.

- King, Marie (1992). "A Most Noble Anchorage - The Story of Russell & The Bay of Islands". The Northland Publications Society, Inc., The Northlander No 14 (1974). Retrieved 9 Oct 2012.

- "New Zealand - Has the Work Died Out?". The Church Missionary Gleaner. 20: 115. 1870. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Binney, Judith. "Penetana Papahurihia". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Chapter 8: The Storming-Party at Ohaeawai", The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, James Cowan, 1955

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 8: The Storming-Party at Ohaeawai". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. p. 71.

- Thomas Hutton, copied from a drawing taken by Mr Symonds of the 99th Regt. (1845). "Plan of Ohaeawai pa". New Zealand History Online. Retrieved 4 Oct 2011.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol. II, The Life of Henry Williams - Letter of Mrs. Williams to Mrs. Heathcote, July 5, 1845. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 115.

- "The Battle for Kawiti's Ohaeawai Pa", James Graham, HistoryOrb.com

- "The Modern Gun-Fighter's Pa (From notes supplied by the late Tuta Nihoniho)". New Zealand Electronic Text Collection. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Gunfighter pā, c1845". New Zealand history online. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Gunfighter Pa" (Tolaga Bay), Historic Places Trust website

- Best, Elsdon (1927). "Old Forts of the Taiamai District, Bay of Islands". The Pa Maori. Whitcombe and Tombs Limited.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Volume I: 1845–1864". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 73–144.

Sources

- Belich, James (1988). The New Zealand wars. Penguin

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 112.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Volume I: 1845–1864". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 73–144.

- Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). Hekes War in the North. No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand Library. pp. 38–46.