Battle of Zama

The Battle of Zama was fought in 202 BC near Zama, now in Tunisia, and marked the end of the Second Punic War. A Roman army led by Publius Cornelius Scipio, with crucial support from Numidian leader Masinissa, defeated the Carthaginian army led by Hannibal.

| Battle of Zama | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Punic War | |||||||

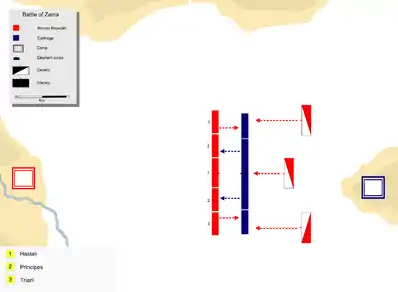

Movements of the opposing armies before the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Kingdom of Numidia |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Publius Cornelius Scipio Massinissa of Numidia Gaius Laelius | Hannibal | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

35,100 men • 29,000 infantry • 6,100 cavalry[2] |

40,000 men • 36,000 infantry • 4,000 cavalry 80 war elephants[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

4,000–5,000 1,500–2,500 Romans killed 2,500+ Numidians killed[3] |

33,500–40,000 Polybius and Livy:

Appian:[4]

| ||||||

Location within modern Tunisia | |||||||

After defeating Carthaginian and Numidian armies at the battles of Utica and the Great Plains, Scipio imposed peace terms on the Carthaginians, who had no choice but to accept them. At the same time, the Carthaginians recalled Hannibal's army from Italy. Confident in Hannibal's forces, the Carthaginians broke the armistice with Rome. Scipio and Hannibal confronted each other near Zama Regia. Hannibal had 36,000 infantry to Scipio's 29,000. One third of Hannibal's army were citizen levies, and the Romans had 6,100 cavalry to Carthage's 4,000, as most of the Numidian cavalry that Hannibal had employed with great success in Italy had defected to the Romans.

Hannibal also employed 80 war elephants. The elephants opened the battle by charging the main Roman army. Scipio's soldiers avoided the elephants by opening their ranks and drove them off with missiles. The Roman and Numidian cavalry subsequently defeated the Carthaginian cavalry and chased them from the battlefield. Hannibal's first line of mercenaries attacked Scipio's infantry and were defeated. The second line of citizen levies and the mercenaries' remnants assaulted and inflicted heavy losses on the Roman first line. The Roman second line joined the struggle and pushed back the Carthaginian assault. Hannibal's third line of veterans, reinforced by the citizen levies and mercenaries, faced off against the Roman army, which had been redeployed into a single line. The combat was fierce and evenly matched. Finally, Scipio's cavalry returned to the battle and attacked Hannibal's army in the rear, routing and destroying it.

The Carthaginians lost 20,000–25,000 killed and 8,500–20,000 captured. Scipio lost 4,000–5,000 men, and 1,500–2,500 Romans and 2,500 Numidians were killed. Defeated on their home ground, the Carthaginian ruling elite sued for peace and accepted humiliating terms, ending the 17-year war.

Prelude

Crossing the Alps, Hannibal reached the Italian peninsula in 218 BC and won several major victories against the Roman armies. The Romans failed to defeat him in the field and he remained in Italy, but following Scipio's decisive victory at the Battle of Ilipa in Spain in 206 BC, Iberia had been secured by the Romans. In 205 BC Scipio returned to Rome, where he was elected consul by unanimous vote. Scipio, now powerful enough, proposed to end the war by directly invading the Carthaginian homeland.[5] The Senate initially opposed this ambitious design of Scipio, persuaded by Quintus Fabius Maximus that the enterprise was far too hazardous. Scipio and his supporters eventually convinced the Senate to ratify the plan, and Scipio was given the requisite authority to attempt the invasion.[6]:270

Initially, Scipio received no levy troops, and he sailed to Sicily with a group of 7,000 heterogeneous volunteers.[7]:96 He was later authorized to employ the regular forces stationed in Sicily, which consisted mainly of the remnants of the 5th and 6th Legion, exiled to the island as a punishment for the humiliation they suffered at the Battle of Cannae.[7]:119

Scipio continued to reinforce his troops with local defectors.[6]:271 He landed at Utica and defeated the Carthaginian army at the Battle of the Great Plains in 203 BC. The panicked Carthaginians felt that they had no alternative but to offer peace to Scipio, and having the authority to do so, Scipio granted peace on generous terms. Under the treaty, Carthage could keep its African territory but would lose its overseas empire, by that time a fait-accompli. Masinissa was to be allowed to expand Numidia into parts of Africa. Also, Carthage was to reduce its fleet and pay a war indemnity. The Roman Senate ratified the treaty. The Carthaginian senate recalled Hannibal, who was still in Italy (although confined to the south of the peninsula) when Scipio landed in Africa, in 203 BC.[8] Meanwhile, the Carthaginians breached the armistice agreement by capturing a stranded Roman fleet in the Gulf of Tunis and stripping it of supplies. The Carthaginians no longer believed a treaty advantageous, and rebuffed it under much Roman protest.[9]

Troop deployment

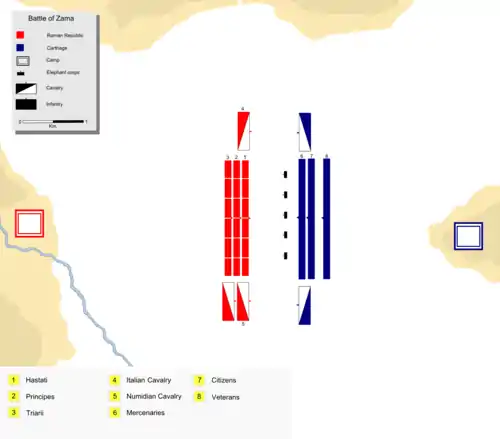

Hannibal led an army comprising Spanish mercenaries, Gallic allies, local citizens and veterans, and Numidian cavalry from his Italian campaigns. Scipio led a pre-Marian Roman army quincunx, along with a body of Numidian cavalry.

The battle took place at Zama Regia, near Siliana 130 km southwest of Tunis. Hannibal was first to march and reach the plains of Zama Regia, which were suitable for cavalry maneuvering. This also gave an edge in turn to Scipio, who relied greatly on his Roman heavy cavalry and Numidian light cavalry. Hannibal deployed his troops facing northwest, while Scipio deployed his troops in front of the Carthaginian army facing southeast.[10]

Hannibal's army consisted of 36,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry and 80 war elephants, while Scipio had a total of 29,000 infantry and 6,100 cavalry.[2] Putting his cavalry on the flanks, with the inexperienced Carthaginian cavalry on the right and the Numidians on the left, Hannibal aligned the rest of his troops in three straight lines behind his elephants.[11] The first line consisted of mixed infantry of mercenaries from Gaul, Liguria and the Balearic Islands. In his second line he placed the Carthaginian and Libyan citizen levies, while his veterans from Italy, including mercenaries from Gaul and Hispania, were placed in the third line.[12] Hannibal intentionally held back his third infantry line, in order to thwart Scipio's tendency to pin the Carthaginian center and envelop his opponent's lines, as he had done at the Battle of Ilipa.[9] Livy states that Hannibal deployed 4,000 Macedonians in the second line. Their presence is widely discounted as Roman propaganda, although T. Dorey suggests that there may be a grain of truth here if the Carthaginians recruited a trivial and unofficial number of mercenaries from Macedonia.[13]

Scipio deployed his army in three lines: the first was composed of the hastati, the second of principes and the third of the triarii. The stronger right wing was composed of the Numidian cavalry and commanded by Masinissa, while the left was composed of Italian cavalry under the command of Laelius. The greatest concern for Scipio was the elephants. He came up with an ingenious plan to deal with them.

Scipio knew that elephants could be ordered to charge forward, but they could only continue their charge in a straight line.[14] He believed that if he opened gaps in his troops, the elephants would simply pass between them without harming any of his soldiers. He created lanes between the regiments across the depth of his forces and hid them with maniples of skirmishers. The plan was that when the elephants charged, these lanes would open, allowing them to pass through the legionaries' ranks and be dealt with at the rear of the army.

Hannibal and the Carthaginians had relied on cavalry superiority in previous battles such as Cannae, but Scipio, recognizing their importance, held the cavalry advantage at Zama. This was due in part to his raising of a new cavalry regiment in Sicily and careful courting of Masinissa as an ally.

Hannibal most likely believed that the combination of the war elephants and the depth of the first two lines would weaken and disorganize the Roman advance. This would have allowed him to complete a victory with his reserves in the third line and overlap Scipio's lines. Though this formation was well-conceived, it failed to produce a Carthaginian victory. The two men are said to have met face-to-face before the battle. Hannibal offered a treaty that would give up any claims to overseas territories to ensure the sovereignty of Carthage. Scipio refused, saying that it was either unconditional surrender or battle.

The battle

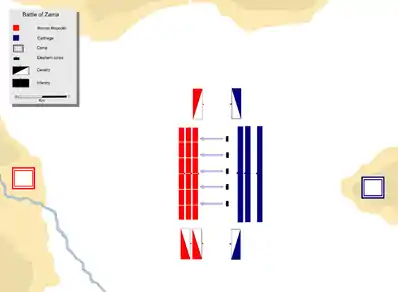

At the outset of the battle, Hannibal unleashed his elephants and skirmishers against the Roman troops in order to break the cohesion of their lines and exploit the breaches that could be opened.[15] The attack was met by Roman skirmishers. In addition, Scipio ordered the cavalry to blow loud horns to frighten the beasts, which partly succeeded, and several rampaging elephants turned towards the Carthaginian left wing and disordered it completely. Seizing this opportunity, Masinissa led his Numidian cavalry and charged at the Carthaginian left wing, which was also composed of Numidian cavalry, and was unknowingly lured off the field. Meanwhile, the rest of the elephants were carefully lured through the lanes and funneled to the rear of the Roman army, where they were dealt with. Scipio's plan to neutralize the threat of the elephants had worked; his troops then fell back into traditional Roman battle formation. Laelius, the commander of the Roman left wing, charged against the Carthaginian right. The Carthaginian cavalry, acting on the instructions of Hannibal, allowed the Roman cavalry to chase them in order to lure them away from the battlefield so that they wouldn't attack the Carthaginian armies in the rear.[16]

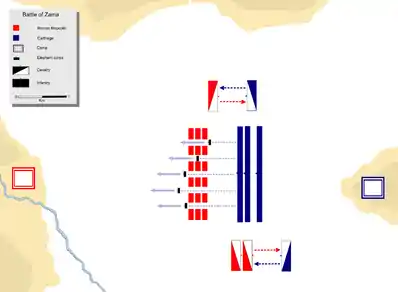

Scipio now marched with his center towards the Carthaginian center, which was under the direct command of Hannibal. Hannibal moved forward with two lines; the third line of veterans was kept in reserve. After a close contest, his first line was pushed back by the Roman hastati.[14] Hannibal ordered his second line not to allow the first line in their ranks. The bulk of them managed to escape and position themselves on the wings of the second line on Hannibal's instructions.[8] Hannibal now charged with his second line. A furious struggle ensued and the Roman hastati were pushed back with heavy losses. Scipio reinforced the hastati with the second-line principes.[10]

Hannibal begins the battle with his war elephants charging at Roman front. Scipio orders his cavalry to blow loud horns to terrify the charging beasts. The panicked elephants turn on the Carthaginian left wing and rampage through it.

Hannibal begins the battle with his war elephants charging at Roman front. Scipio orders his cavalry to blow loud horns to terrify the charging beasts. The panicked elephants turn on the Carthaginian left wing and rampage through it. Roman right wing charges and routs the Carthaginian cavalry, followed by the Roman left wing routing the Carthaginian right wing. The remaining elephants are lured through the lanes and killed.

Roman right wing charges and routs the Carthaginian cavalry, followed by the Roman left wing routing the Carthaginian right wing. The remaining elephants are lured through the lanes and killed. Carthaginian cavalry routed off the field. Scipio attacks Hannibal's first and second lines of infantry and routs both.

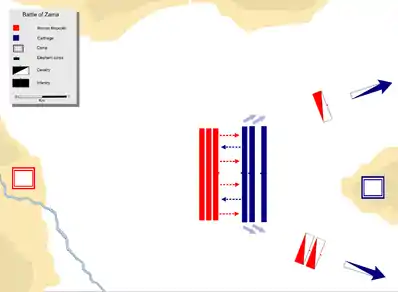

Carthaginian cavalry routed off the field. Scipio attacks Hannibal's first and second lines of infantry and routs both. Scipio and Hannibal rearrange their troops into a single line and the battle remains a stalemate until the Roman cavalry returns and attacks Hannibal's infantry from the rear.

Scipio and Hannibal rearrange their troops into a single line and the battle remains a stalemate until the Roman cavalry returns and attacks Hannibal's infantry from the rear.

With this reinforcement the Roman front renewed their attack and defeated Hannibal's second line. Again, it was not allowed to merge with the third line and was forced to the wings, along with the first line. Carthaginian cavalry carried out Hannibal's instructions well and there was no sign of Roman cavalry on the battlefield. Once the Carthaginian cavalry was far enough away, they turned and attacked the Roman cavalry but were eventually routed. At this point there was a pause in the battle as both sides redeployed their troops. Scipio played for time as he redeployed his forces in a single line with the hastati in the middle, the principes in the inner wings and the triarii on the outer wings. Hannibal waited for Scipio to attack. The resulting clash was fierce and bloody, with neither side achieving superiority. Scipio was able to rally his men.[14] The battle finally turned in the Romans' favor when the Roman cavalry returned to the battlefield and attacked the Carthaginian line from behind. The Carthaginian infantry was encircled and annihilated. Thousands of Carthaginians, including Hannibal, managed to escape the slaughter.[9] Hannibal experienced a major defeat that put an end to all resistance on the part of Carthage. In total, as many as 20,000 of Hannibal's troops were killed at Zama, while 20,000 more were taken prisoner. The Romans suffered 2,500 dead.[17]

Aftermath

Soon after Scipio's victory at Zama the war ended, with the Carthaginian senate suing for peace. Unlike the treaty that ended the First Punic War, the terms Carthage acceded to were so punishing that it was never able to challenge Rome for supremacy of the Mediterranean again. The treaty bankrupted Carthage and destroyed any chance of its being a military power in the future. Scipio returned to Rome a hero and was almost immediately granted a Triumph by the senate.

Hannibal inially returned to Carthage and went into civilian politics; under his leadership Carthage experienced a rapid post-war economic recovery. This startled the Romans, who considered the Carthaginian general a great potential threat as long as he lived. Hannibal still had many enemies both inside and outside of Carthage. Due to pressure from both Rome and domestic political rivals, Hannibal voluntarily stepped down from power and went into exile. For the rest of his life, he traveled across the Mediterranean, offering his service to any polity waging war against Rome. Though many were eager to accept his offer, Hannibal ultimately failed to check Roman expansion. In 184BC, facing imminent capture, Hannibal chose suicide instead.[18][19]

One provision of the treaty ending the Second Punic War was that the Carthaginians were not allowed to make war without Roman consent. This allowed the Romans to establish a casus belli for the Third Punic War about 50 years later, after the Carthaginians defended themselves from Numidian encroachments, against which the Romans did not initially intervene. By then, Carthaginian power was a shadow of its former self. Though they fought with some success early on, the Carthaginians simply could not defeat the by-then very aged Masinissa once the armies of his Roman allies arrived in Africa. Unable to field a viable force in open combat and abandoned by all of their Punic allies, the Carthaginians commenced a spirited defense of their home city which, after an extended siege, was captured and completely destroyed in 146 BC. Only 55,000 of the city’s inhabitants survived, almost all of whom were sold into slavery by the Romans.[10]

Notes

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 406. supports the 19 October date.

However, Cary, M. (1967). History of Rome: Down to the Reign of Constantine. London: Macmillan. p. 173. gives the date as "summer of 202". - Lazenby, Hannibal's War, pp.220–221

- "Appian, The Punic Wars 10". Livius. Retrieved 2021-01-09.

- Appian, Appian

- Livy, 28.40

- Bagnall, Nigel, The Punic Wars

- Liddell Hart, Basil Henry, Scipio

- Davis, William Stearns, Readings in Ancient History – Illustrative Extracts from the Sources, p. 79, ISBN 1-4067-4833-1

- Delbrück, Hans, History of the Art of War: Warfare in antiquity, p. 393, ISBN 0-8032-9199-X

- Nardo, Don, The battle of Zama, p. 30, ISBN 1-56006-420-X

- Carey, Hannibal's Last Battle, p.116

- Frontinus, Sextus Julius (1925), Bennet, Charles E (ed.), Stratagemata, Classical library, Loeb, p. 114, ISBN 0-674-99192-3,

...novissimos Italicos constituit, quorum et timebat fidem et segnitiam verebatur, quoniam plerosque eorum ab Italia invitos extraxerat

- Dorey, TA (1957), "Macedonian Troops at the Battle of Zama", The American Journal of Philology, 78, pp. 185–7

- Africanus, Scipio; Hart, BH Liddell; Grant, Michael, Greater Than Napoleon, p. 263, ISBN 0-306-81363-7

- Scullard, Howard Hayes (1930), Scipio Africanus in the second Punic war, CUP Publisher Archive

- Goldsworth, Adrian (2006), The Fall of Carthage, The Punic Wars 265–146 BC, Phoenix, p. 304

- Adrian Goldsworthy, The Fall of Carthage, The Punic Wars 265–146 BC, Phoenix, 2006, pp. 305–307

- www.biography.com/.amp/military-figure/hannibal

- www.historynet.com/why-hannibal-lost.htm

References

- Paul K. Davis (2001-06-14). 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9.

- Hans Delbruck (1990). Warfare in antiquity. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9199-7.

- Theodore Ayrault Dodge (2004-03-30). Hannibal: A History of the Art of War Among the Carthaginians and Romans Down to the Battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., with a Detailed Account of the Second Punic War. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81362-7.

- Steven James. "The Army and Fleet of Publius Scipio's African Campaign: 204 BC".

- Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart (1926). Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon. Greenhill Press. ISBN 978-1-85367-132-6.

- Robert F. Pennel; Ancient Rome from the earliest times down to 476 A.D; 1890

- Polybius; The general history of Polybius, Volume 2; W. Baxter for J. Parker, 1823

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Zama. |

- The Battle of Zama

- Battle of Zama from UNRV History