Battle of the Windmill

The Battle of the Windmill was a battle fought in November 1838 in the aftermath of the Upper Canada Rebellion. Loyalist forces of the Upper Canadian government and American troops, aided by the Royal Navy and U.S. Navy,[2] defeated an invasion attempt by a Hunter Patriot para-military unit based in the United States, which had the intention of using the beachhead as a launchpad for further offensives into Canada. Canadian, British, and American troops thwarted the invasion, successfully defending Canadian soil and forced the invaders to surrender. Others still in the U.S. were captured and arrested by U.S. officials.

| Battle of the Windmill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Patriot War, Rebellions of 1837 | |||||||

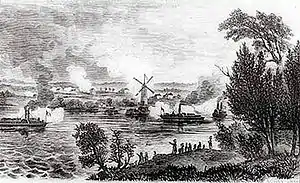

Contemporary engraving of the Battle of the Windmill as seen from the American shore. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Hunters' Lodges |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Nils von Schoultz | Henry Dundas | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 250 Hunter invaders |

British: 1,133 Canadian militia 500 British regulars Royal Navy American: U.S. Army U.S. Navy[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

53 dead 61 wounded 136 captured |

17 dead 60 wounded | ||||||

- The "Battle of the Windmill" is also a fictional battle in the book Animal Farm.

Background

After a rebellion by disaffected Upper Canadians was suppressed in 1837, the majority of the rebel leaders fled to the United States. Popular sentiment in the States held that Canadians were eager to overthrow British rule and form a republic patterned after the American model.

An organization known as the Hunter Patriots was formed to assist the rebellion. Organized in neo-Masonic secret lodges, and with widespread support in the northern border states from Vermont to Wisconsin, the Patriot Hunters aimed to invade Canada and lead an army of insurgent Canadians against the British colonial government. In reality, much of the Canadian population was loyal to existing British institutions and decidedly against the prospects of revolution or invasion.

In November 1838, a group of Hunter Patriots decided that it was time to invade Canada and restart the rebellion. They chose as their target the town of Prescott, on the north bank of the St. Lawrence River downriver from Kingston. Prescott is the site of Fort Wellington, a British military fortification that commanded the St. Lawrence River and was serving as a fortified depot for the Upper Canadian militia. To initiate the strike, a large group of Hunters assembled in Sackets Harbor, New York and descended the river to Ogdensburg in civilian vessels. Overall military command of the invading forces was held by John Birge, a senior member of the Hunter organization in New York state. [3]

Attempted seizure of Prescott

Early in the morning of November 12, a force of about 250 men attempted to land in Prescott. However, the British had infiltrated the Hunter organization, and had advance warning of the attack. With the element of surprise gone, and with the town militia ready to repel a landing, the Hunter forces abandoned the landing. Their vessels ran aground on a mud flat where the Oswegatchie River flows into the St. Lawrence off Ogdensburg.

Later in the morning, Bill Johnston, Admiral of the Hunter navy, arrived and freed the stranded vessels, which then ran downriver to Windmill Point, a promontory located approximately two miles east of Prescott. Here, most of the Hunter forces landed to occupy the hamlet of Newport and its most prominent feature, a large, stone windmill building that enjoyed a panoramic view of the St. Lawrence River as far west as Brockville and eastwards over the Gallop Rapids. The commanders of the Hunters appointed a Swedish immigrant with some military experience, Nils von Schoultz, to command the Hunter forces while the Hunter leadership withdrew to Ogdensburg to collect reinforcements and supplies.

First assault

The windmill was built of thick stone and stood 60 feet (18 m) high on top of a 30-foot (9.1 m) bluff. Although the attackers had not planned to use the structure, it provided an ideal fortified position. Its height prevented the British forces from approaching unobserved, and its thick stone walls were impervious to small arms and to small field and naval artillery. Early on the morning of 13 November, a force under the command of the militia officers Colonel Plomer Young, Colonel Richard Fraser, Captain George Greenfield Macdonell,[4][5] and Colonel Ogle Gowan and comprising a handful of British infantry from the 83rd Regiment and approximately 600 Canadian militiamen invested the Hunter position around Newport and attacked. The attack failed, leaving 13 regulars and militiamen killed and 70 wounded. The Hunters suffered about 18 killed and some wounded.

The next several days were a standoff. As time passed, von Schoultz's position became desperate. Promised reinforcements and supplies never arrived as the United States Navy aided the Royal Navy in blocking egress from Ogdensburg. Law enforcement and military officials in Ogdensburg secured available vessels, and most of the prominent Hunter leaders fled from town to avoid arrest.

Second assault

Heavy artillery from Kingston, as well as sizeable detachments of British Army regulars, Canadian militia and U.S. Army regulars,[6] tried to strengthen the Canadian forces. An artillery bombardment of the windmill was conducted on November 16. Royal Navy gunboats and steamers, and ships of the U.S. navy blocked the Hunters from escaping, and Hunter casualties mounted, so von Schoultz unconditionally surrendered.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the battle, almost all of the Hunters were captured and were transported to Kingston for trial. Eleven people, including the Hunter leader Nils von Schoultz, were executed; another 60 were sentenced to transportation to Australia. 40 were acquitted, and another 86 were later pardoned and released. Von Schoultz enjoyed the legal counsel of John A. Macdonald, a prominent young Kingston lawyer who would later become the architect of Canada's Confederation in 1867 and Canada's first prime minister.

The site of the battle was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1920.[7][8]

Further reading

- Graves, Donald E. (Donald Graves) (2001). Guns Across the River: The Battle of the Windmill, 1838. Friends of Windmill Point. ISBN 1-896941-21-4

References

- Bonthius, Andrew (2003). "The Patriot War of 1837–1838: Locofocoism With a Gun?". Labour/Le Travail. 52: 10–11. doi:10.2307/25149383. JSTOR 25149383. S2CID 142863197.

- Bonthius, Andrew (2003). "The Patriot War of 1837–1838: Locofocoism With a Gun?". Labour/Le Travail. 52: 10–11. doi:10.2307/25149383. JSTOR 25149383. S2CID 142863197.

- Guns Across the River: The Battle of the Windmill, 1838 by Donald Graves

- "Remembering the Battle of the Windmill". Recorder & Times.

- "The Battle of the Windmill: A soldier's version". Recorder & Times.

- Bonthius, Andrew (2003). "The Patriot War of 1837–1838: Locofocoism With a Gun?". Labour/Le Travail. 52: 10–11. doi:10.2307/25149383. JSTOR 25149383. S2CID 142863197.

- Battle of the Windmill, Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada

- Battle of the Windmill. Canadian Register of Historic Places.