Bazaar of Pristina

The Bazaar of Prishtina (Albanian: Çarshia e Prishtinës; Serbian: Базар у Приштини, romanized: Bazar u Prištini), Kosovo[a], was the core merchandising center of the Old Prishtina since the 15th century, when it was built.[1] It played a significant role in the physical, economic, and social development of Pristina. The Old Bazaar was destroyed during the 1950s and 1960s, following the modernization slogan of "Destroy the old, build the new". In its place, buildings of Kosovo Assembly, Municipality of Prishtina, PTT, and Brotherhood and Unity socialist square were built. Nowadays, instead of PTT building resides the Government of Kosovo building. Only few historical buildings, such as the Bazaar Mosque and ruins of the Bazaar Hammam have remained from the Bazaar complex.[2] Since then, Prishtina has lost part of its identity, and its cultural heritage has been scattered.

History

Bazaars (English marketplace, Turkish pazar, Serbian базар, Albanian çarshia) were unique trading complexes developed in the towns of Kosovo and elsewhere in the Balkans, while the area came under the Ottoman Empire. They were built during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, reaching their final shape in the 19th century.[3] These traditional complexes were developed in two types: the Covered Bazaar or Bezistan and the Open Bazaar. While the first was a closed complex of stores, the second was characterized by consecutive rows of crafts shops, where on Tuesdays merchants exposed their products. Before their construction, people used to expose their crafts on the mosque walls, at the time being practiced only in Albanian towns.

In the 13th century, Pristina was referred to as a “village”, and in 1525 as a town, but was officially recognized only in 1775.[4][5] During the 14th and 15th centuries, it became an important mining and trading center.[6] As a Medieval trading center, the first merchants' shops emerged in the 16th century. In 1660, Evliya Çelebi claims that Pristina had a market area (Bazaar), a hammam, 11 khans and about 300 different shops.[4][7] Shops were located in the Old Bazaar, which in the 18th and 19th century, was the most important economic entity. According to Ammie Boue, in 1830, the Old Bazaar was the central core of Pristina.[8] At this time (1840), Bazaar of Pristina had around 200 crafts shops.[9]

At this time, Pristina was also known for the tradesmen and craftsmen organized fairs. The first and biggest fair was in 1879, where 1200-1500 people were present.[10] Branislav Nušić, the vice-consul of Kingdom of Serbia, after visiting Pristina in 1893-96, claimed that it had the liveliest trade.[11][12] According to Nušić, in 1902 Pristina had 500 shops, 12 khans, 12 mosques, 1 Clock tower, and some warehouses.[13][14] Between two World Wars, Pristina had 240 shops, mostly focused in the Old Bazaar.[7] In the verge of Second World War, there were 365 private crafts shops, practicing about 60 different crafts.[15] After the war, economy was industrialized, and crafts started fading.

Urban and social context of the Bazaar

Urban context

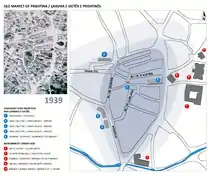

The Old Bazaar of Pristina was located in the core center of Pristina, exactly at the intersection of the two main roads, which influenced its physical, economic, and social developments.[16] These arteries were the east-west direction or Divan-Yoll (today UÇK Street), and the north-south road (Corso, today Mother Teresa boulevard). Divan-Yoll was distinguished for the development of public domain and social life of the inhabitants, while the other road was important for the economic development.[17] Along the north-south artery, a convoy of caravans were passing through to the other important cities of the Balkans, which influenced the development of Pristina.

On the other hand, bazaars were preferable to be located close to rivers, therefore Bazaar of Pristina was located approximately in-between Vellusha and Prishtevka rivers. Nowadays, both these rivers are covered.[18] It was surrounded by Bedri Pejani Street in the west, UÇK Street in the north, Agim Ramadani Street in the east, and Mother Theresa Boulevard in the south.[19] The most crowded area with shops was at the nowadays Government area.[19]

Bazaar was not preliminary planned, but spontaneously developed along the organic network of roads.[20] The main streets intersected at a rhombic square with a Round Fountain in the middle.[21] These narrow roads were paved with cobblestones or macadam, and were kept very clean.[8] In the 1950s, law for cleaning the streets was approved, according to which citizens were supposed to clean their gardens, shops, and streets, and then pile the garbage, which was later taken away by a phaeton.[8] The Bazaar's streets were composed of parallel rows of single-story jointed shops.[22] The residential areas were located outside the Bazaar, in a radial direction.

Architectural context

The bazaar was structured accordingly with the practiced crafts; hence each craft had its own alley.[23] This principle was inherited from the Eastern Roman Empire.[22] Bazaar stores were made of three main materials: adobe, wood, and stone. Masonry was made of adobe and stone. The roof structure, frontal facade, windows and eventually floor and ceiling were made of wood. In both functional and architectural viewpoint, the most important element of the stores was its frontal facade. The bazaar shops’ street facades were characterized by long eaves, large wooden windows, and multifunctional window shutters. During the day, while the shops were open, these wooden shutters they were used as exposition racks.[24] Opening and closing of the frontal shutters beside the door indicated whether the store was open or not for customers.

In general, bazaar shops were architecturally designed as single-story constructions, where the ground floor area was used for crafts-working, exposition, and trading area. Shortly, the same space was used for storing the raw material, manufacturing the artisanal products, and later exposing them for sale.[25] Sometimes, besides the ground floor they also had an upper floor, mostly used as depot. Only during the second half of the 19th century they had two stories above.[22] Among the shops, there were also some small cafes serving coffee, tea, and occasionally rakia.[21]

The residential areas were located outside the Bazaar, in a radial direction, in the organic mahallas of Pristina. Houses were built in ground and first floor levels, which were constructed of strong materials and covered with tiles. Despite the influences of European architecture, their architecture remained native. These houses had great gardens, surrounded by exterior walls for family protection and privacy.

Social context

Bazaar was the most important trade and crafts center. It was famous for its annual trade fairs and goat hide and hair articles. Most notable traders were Jews, who were relatively educated and besides their own language also spoke Turkish, Serbo-Croatian, and Albanian.[10] Bazaar of Pristina was also visited by other traders, mostly by Ragusans (from nowadays Dubrovnik), who became a vast colony. Being in such crossroads, Bazaar served as a linkage of local and other foreign craftsmen.[6]

Craftsmanship and commerce networks were organized in guilds. Guilds were an Ottoman model of the corporate economy organizations.[26] They protected economic, social, political, military, religious, educational and other craftsmen interests. These guilds had a common voluntary fund, which was used to financially support poor and ill craftsmen, to educate young artisans, to establish schools and build some public buildings.[27][28] On the other hand, they controlled the economic life, especially the tanners and bakers guilds, which controlled the prices.[6]

Besides trading, Bazaar of Pristina was also the main place for public encounters.[21] Its shops were also used for blood feud reconciling, selling and purchasing of property, affiancing procedures, setting of marriage dates, developing patriotic feelings, and cultivating trust or Besa.[28] Closeness of shops made people get closer with each other. There was a lot of respect among them.[29] People used to hang around and drink tea with each other in front of their shops.[30] Whenever a new shop opened, people used to throw coins on the ground, believing that this superstitious act would bring fortune. Other signs of good luck were horseshoes, and garlic head or horn.[31]

Important building landmarks

- Bazaar Mosque

Bazaar or Carshı Mosque was initially started in 1389 as a mark of Ottoman forces victory in Kosovo Was, and finished in the beginning of the 15th century, by Sultan Bayazid.[32] It was the first mosque built in Kosovo.[6] By that time, it used to overlook over the covered part of Bazaar. Since then, Bazaar Mosque has gone through significant changes, being initially repaired in 1820 and 1902 by Sulltan Abdylhamid II.[10] As a result, its original look has been modified, but the stone-topped minaret, its distinguishing symbol, has been preserved for more than a half millennium, respectively 600 years.[32] Carshı Mosque is also known as ‘Tas Mosque’, which literally means ‘Stone Mosque’.[32][33] Bazaar It is one of 21 protected buildings in Pristina,[32] listed since 1967.

- Bazaar Hammam

Bazaar or Old Hammam is assumed to have been built in the 15th century, approximately at the same time as the Great Hammam of Pristina.[2] As a public bath for cleaning and recreation, it was an important part of Bazaar.[9] The Old Hammam was located just in front of the Bazaar Mosque. Following the destruction of the Baazar, Hammam was ruined too. Its stone foundations were found during the construction of today’s Kosovo Assembly building, in 1959.[2] Besides of their listing for state protection, they were covered and no further researches of the Hammam building and site have been made.[32]

- Khan

Khans or inns were specific buildings located in Pristina’s Bazaar that offered accommodation for traders and their animals, serving as a facilitation of trade. Khan consisted of two floors. Ground floor was a shelter for animals, whereas the upper one was a shelter for people. There were served coffee, tea, and food. In 1870-1880 Pristina possessed around 10 Khans.[9] Before Second World War there were 3 khans located in Korzo Street in the Old Bazaar.

- Bezistan

In 1830, Pristina had a Covered Bazaar known as Bezistan.[9] Among the inhabitants it was also known as "Kapalı Çarshı", according to the Turkish language. This structure was a distinguished road with parallel consecutive shops, surrounded by walls and closed with huge arched doors at both sides of the road.[9] It was covered with bricks for around 15–20 meters at its entrance.[8] The high security enabled safety provisions while trading valuable goods.[9] The covered complex had nearly 150-200 crafts shops.[10] Interior of the Bezistan was attractive and interesting, thus resembling the bazaars of many oriental kasabas.[10] Covered Bazaar is supposed to have been located in the southern part of the Open Old Bazaar, in-between Carshı Mosque in the east and Korzo Street in the west; nowadays, approximately near the building of Assembly of Kosovo.[10] In its western exit, between the crafts shops, complex was The Round Sadirvanc(“Shadërvani Rrethor”) with one fountain-head and concrete tub.[10] Water from the fountain on the lower part of Bazaar, was used for maintaining the shops and other needs of inhabitants.[10]

- Synagogue

Synagogue, named "Havra-Sinagoga", was located in the southwestern part of the Bazaar, near the end of the Bezistan.[16][19] It was used by Jews for their Saturday rituals. These Jews living in Pristina, were owners of many shops and their houses were lined along the Divan-Yol Street.[8]

- Bazaar Tekke

Bazaar Tekke was located near the western exit of the Covered Bazaar.[34] It has also been destroyed.

Shops and crafts

Shops were decorated and filled with goods. There were shops of moccasin shoes, saddlers, curriers, Albanian fez makers, etc.[10] Among which were from tanning to leather dyeing, belt making and silk weaving, and also military crafts as armorers, smiths, and saddle makers. In 1485 the artisans started producing gunpowder.[6] There were also many cafés and tea shops, sweet-shops, and bakers. There were also other shops were oriental foods were served, kebab stores, butchers, pharmacies, libraries, barbers, watchmakers.[10]

There were around 50 different handicrafts practiced in the Bazaar of Pristina.[6] They were crafted by gifted silversmiths, goldsmiths, coppersmiths, tinsmiths, blacksmiths, gunsmiths, tub-makers, cutlers, potters, farriers, saddlers, boot makers, tailors, quilters, and curries.[7][28] Especially Pristina was known as the center of coppersmiths and pottery crafting, which spread later in other Kosovo cities, such as Prizren, Gjakova, Peja, Gjilan. Copper pots were crafted for domestic and cult purposes. These pots were crafted from copper and brass by forging, smelting and savat techniques. On the other hand, clay pots were crafted for wheat and water preservation (water vessels and jugs). Decorations used in these crafts were wavy zigzag lines, circles, and semicircles.[28]

Saddling was also developed in Pristina, besides Gjakova, Prizren, Gjilan, and Peja. Among the crafts were: horse and oxen gears, such as bridles, halters, tacks, collars, headgear, pads, saddles, stirrups, and cuirasses. These supplies were decorated with beads, charms, tufts, and mirrors.[28]

Pristina was also identified with tailoring and silk processing. Tailors used to make national costumes mostly for wealthy class men and women. Among these items were waistcoats, coats, and robes.[28]

Craftsmen of Pristina manufactured slippers as well. Slippers were made of soft leather (sahtian) fabric, embroidered with golden colored strings on the top. There were also shoe-crafts as leather shoes or moccasins, and clogs adorned with silver or pearly incrustation.[28]

Crafts considered as touristic attractions containing folkloric elements, were supported with suitable shops and lower taxes.[7] Also new crafts emerged as: radio-technicians, electro-technicians, hydro-installers, auto-mechanics, etc.[7] Nowadays, most of handicrafts do not exist or have been transformed into new trades. Some of them are the handicraft of curriers, saddlers, tailors, silk processors, goat wool rug makers, and embroiders potters. On the other hand, even though in a small number, the old craft shops that still exist are blacksmiths and cutlers.[28]

Destruction of the Bazaar

Early destruction

Bazaar and some other parts of Pristina were destroyed by two great fires in 1859 and 1863, just while Pristina was having its peak development.[35][8][10]

In 1912, following the Serbian invasions, many feudal and intellectual Albanian and Turkish families were deported to Turkey. Among them were the main town’s craftsmen. As a result, the shops were abandoned and Bazaar significance started fading.[14]

Destroy the old, and build the new

The peak of communist politics was during the 1950s when the urban development was established under the motto “Destroy the old, build the new’.[36][32] Pristina had eastern features till the end of the Second World War. After this period destruction of these characteristics and old parts of the city took place.[36] The Ottoman bazaar and large parts of the historic center (including mosques, churches, houses) were destroyed.[6]

A significant part of old Pristina was destroyed to be replaced later with newer architecture.[2] Old buildings were substituted with new ones, and streets were widened and paved with cobblestones. Few remaining old buildings, belonging to Ottoman period, were left without institutional care.[37]

"Until the end of World War II, Pristina has been a typical oriental city. After liberation, Pristina experienced rapid development, becoming a modern city. Shops and unstable old structures started disappearing, making space for building high buildings of modern style”.[10]

The so-called “Unstable old structures”, which covered one of the largest bazaars in the region were demolished after the war.[38] This spiritual center of the city has lost its mosque, a catholic church and synagogues. Since the 1945, the story of Pristina is a gray, tragic story of its destruction and many misfortunes. During the communist era, the annihilation of the past was the outcome of non liberal politics.[38]

In the aftermath of World War Two, Yugoslavia was governed by communist authorities who implemented various modernisation drives toward changing the architectural landscape and design of urban settlements.[39] These measures were aimed at altering the panorama of a settlement that was deemed to have elements associated with an unwanted Ottoman past and features deemed as "backward".[39] Starting from the late 1940s, architectural heritage in main urban centres of Kosovo began to be destroyed, mainly conducted by the local government as part of urban modernisation schemes.[40] During the 1950s this process was undertaken by the Urban Planning Institute (Urbanistički zavod) of Yugoslavia with the most prominent example in Kosovo of the socialist modernisation drive being in Pristina.[40] The Ottoman Prishtina bazaar contained 200 shops set in blocks devoted to a craft or guild owned by Albanians grouped around a mosque, located in the centre of Prishtinë.[40] These buildings were expropriated in 1947 and demolished by labour brigades known as Popular Fronts (Albanian: Fronti populluer, Serbian: Narodnifront).[40]

After the Second World War in 1953, Pristina had its first urban plan, made by Serbian architect Partonic, approved. Citizens, eager for modern city, volunteered in the new city order. This was the starting point of the Bazaar destruction where many crafts shops were ruined to make space for the new Municipality Assembly and Parliament of Kosovo.[10] Everything ‘old’ and of Albanian and Turkish roots was destroyed; only a few remained.[10] At that time, some Russian architects insisted on preserving the Bazaar’s architecture. Nevertheless, the system decided to destroy everything.[8]

In 1954, a master plan was approved by Institute for the Protection and Study of Cultural Monuments. The main element of it was the placement of a complex of new municipal and provincial government buildings at its center, where the Ottoman-era bazaar of Pristina was located. In the second half of the 1950s, some of the new buildings intended in Pristina’s master plan were constructed such as: a provincial assemblage building, a city hall, and a new main street with modernist mixed-use buildings.[38] All these buildings were located on the site of Pristina’s destroyed bazaar or next to other condemned Ottoman-era architecture. The destruction of Ottoman-era architecture signified the beginning of modernization.[38]

The most radical transformations in Bazaar of Pristina happened from 1960 to 1970.[14] At this time, its small shops, streets, religious and other public buildings were destroyed for the sake of the new. Thus Pristina lost an important feature of its historic and cultural heritage. On the other hand, the shops’ destruction affected the craftsmen's lives. Some of them never recovered their businesses or migrated abroad.[41]

Pristina was turned into an administrative town, from town of gardens and artisans. In the Bazaar area, new administrative buildings were built.[23] In 1965, there was a public debate held among local experts of architecture and other relevant fields, city officials and citizens, who criticized this Urban Plan, which the architect could not justify. Since then, local experts made corrections and undertook further urban developments of Pristina.[10] In 1966, few roads were paved and new high-rise socialist apartment blocks were built.[28]

Nowadays Bazaar area

Bazaar area in 1960 and 2007 |

Bazaar area in 1960 and 2007 |

Photo gallery

- Old Bazaar of Prishtina before 1960

Narrow streets in the Old Bazaar

Narrow streets in the Old Bazaar Shopping street in Prishtina

Shopping street in Prishtina Shopping street in Prishtina

Shopping street in Prishtina Architecture of the shops

Architecture of the shops Architecture of the shops

Architecture of the shops Old Bazaar of Prishtina

Old Bazaar of Prishtina Shopping in the Old Bazaar

Shopping in the Old Bazaar Exposition of the goods

Exposition of the goods Rhomboid square at the Bazaar

Rhomboid square at the Bazaar Destruction of Bazaar

Destruction of Bazaar Destruction of Bazaar

Destruction of Bazaar Building of Brotherhood and Unity Monument

Building of Brotherhood and Unity Monument Destruction of Bazaar shops

Destruction of Bazaar shops Building of Kosovo Parliament building

Building of Kosovo Parliament building Building of Kosovo Parliament building

Building of Kosovo Parliament building Entrance at Bazaar from Divan-Yol

Entrance at Bazaar from Divan-Yol

See also

Notes

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008. Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 98 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 113 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition. |

References

- CHWB (2008). Heritage of Prishtina (PDF). Prishtinë: CHWB. p. 61. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- ESI (2014). "Foundations of the Old Hammam (listed since 1959)".

- DRANCOLLI, Fejaz (2004). Destruction of Albanian Kulla. Prishtinë. p. 24. ISBN 9951861407.

- CHWB (2008). Heritage of Prishtina (PDF). Prishtinë: CHWB. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- Komuna e Prishtinës (1987). Plani i përgjithshëm urbanistik i Prishtinës deri në vitin 2000. Prishtinë: Komuna e Prishtinës. p. 16.

- WARRANDER, G.; KNAUS V. (2010). Kosovo (II ed.). England: Bradt Travel Guides Ltd. p. 86. ISBN 9781841623313.

- CAKA, Nebi; BYLYKBASHI, Zija (2005). Në udhëkryqe të jetës. Prishtinë: Gjimnazi "Sami Frashëri". p. 138. ISBN 9951470009.

- GASHI, Sanije (2012). Prishtina e fëmijërisë sime. Prishtinë: TEUTA. p. 20. ISBN 9789951855730.

- RIZA, Emin; HALITI (2006). Banesa qytetare kosovare e shek. XVIII-XIX. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. pp. 37–39. ISBN 9951413374.

- SYLEJMANI, Sherafedin (2010). PRISHTINA IME. Prishtinë: JAVA MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION. p. 9. ISBN 9789951471022.

- NUSIC, Branislav (1902). KOSOVO: Opis zemlje i naroda. Pristina: Jedinstvo. p. 47.

- BATAKOVIC, D. (2007). Kosovo and Metohija: Living in the Enclave (PDF). Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. p. 228. ISBN 9788671790529.

- NUSIC, Branislav (1902). KOSOVO: Opis zemlje i naroda. Pristina: Jedinstvo. p. 48.

- ISMAJLI, Rexhep, ed. (2011). Kosova: Vështrim monografik. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. p. 165. ISBN 9789951413961.

- CAKA, Nebi; BYLYKBASHI, Zija (2005). Në udhëkryqe të jetës. Prishtinë: Gjimnazi "Sami Frashëri". p. 140. ISBN 9951470009.

- CHWB (2008). Heritage of Prishtina (PDF). Prishtinë: CHWB. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- CHWB (2008). Heritage of Prishtina (PDF). Prishtinë: CHWB. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- RIZA, Emin; HALITI (2006). Banesa qytetare kosovare e shek. XVIII-XIX. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. p. 37. ISBN 9951413374.

- SYLEJMANI, Sherafedin (2010). PRISHTINA IME. Prishtinë: JAVA MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION. p. 22. ISBN 9789951471022.

- Plani zhvillimor urban. Prishtine: Komuna e Prishtines. 2012.

- SHUJAKU, Valbona (2011). Prishtina Poetic Memories. Kosovo: Re: public. p. 2. ISBN 9789951882408. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- ISMAJLI, Rexhep, ed. (2011). Kosova: Vështrim monografik. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. p. 496. ISBN 9789951413961.

- SHUJAKU, Valbona (2011). Prishtina Poetic Memories. Kosovo: Re: public. p. 1. ISBN 9789951882408. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- SHUJAKU, Valbona (2011). Prishtina Poetic Memories. Kosovo: Re: public. p. 3. ISBN 9789951882408. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- RIZA, Emin; HALITI (2006). Banesa qytetare kosovare e shek. XVIII-XIX. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9951413374.

- ISMAJLI, Rexhep, ed. (2011). Kosova: Vështrim monografik. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. p. 166. ISBN 9789951413961.

- ISMAJLI, Rexhep, ed. (2011). Kosova: Vështrim monografik. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. p. 410. ISBN 9789951413961.

- ISMAJLI, Rexhep, ed. (2013). Kosova: A monographic Survey. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. p. 411. ISBN 9789951615105.

- GASHI, Sanije (2012). Prishtina e fëmijërisë sime. Prishtinë: TEUTA. p. 50. ISBN 9789951855730.

- GASHI, Sanije (2012). Prishtina e fëmijërisë sime. Prishtinë: TEUTA. p. 63. ISBN 9789951855730.

- ISMAJLI, Rexhep, ed. (2011). Kosova: Vështrim monografik. Prishtinë: Akademia e Shkencave dhe Arteve të Kosovës. p. 411. ISBN 9789951413961.

- IKS and EKS. "Trashegimia e Prishtines" (PDF). Express. Prishtine (2006): 8–11.

- HULAJ, Jehona. "S'ka "lekë" për restaurimin e Xhamisë së Çarshisë". ZERI. Prishtine (2014). Archived from the original on 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- SYLEJMANI, Sherafedin (2010). PRISHTINA IME. Prishtinë: JAVA MULTIMEDIA PRODUCTION. p. 74. ISBN 9789951471022.

- Komuna e Prishtinës (1987). Plani i përgjithshëm urbanistik i Prishtinës deri në vitin 2000. Prishtinë: Komuna e Prishtinës. p. 17.

- IKS and ESI. (PDF) (2006). Prishtina: 20 http://www.esiweb.org/pdf/esi_future_of_pristina%20booklet.pdf. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - KALAJA, Besa (2014). "Prishtina e vjetër po zhduket". PREPORTR.

- HERSCHER, Andrew (2006). "Counter-Heritage and Violence" (PDF). Future Anterior. pp. 24–33.

- Herscher 2010, pp. 28–29.

- Herscher, Andrew (2010). Violence taking place: The architecture of the Kosovo conflict. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9780804769358. "Kosovo was a province of the Ottoman empire for five centuries and its territory contained many examples of Ottoman architecture, yet only one Ottoman-era monument, the Sultan Murat Turbe, was classified as “cultural monument” in this period; the other such monuments were drawn from the patrimony of the Serbian Orthodox Church.... Premodernity was reified not only by preservation of its treasured signs, however, but also by the elimination of its obsolete components: an abject heritage whose purpose, in modernization, was to be destroyed. This destruction was also institutionalized in socialist modernization. By the 1950s, this modernization was the responsibility of the Urban Planning Institute (Urbanistički zavod) in the capital cities of all republics. Before then, however, destruction was also planned and managed by local governments as part of urban modernization schemes. In Kosovo, beginning in the late 1940s, the destruction of abject heritage took place in each major city, most prominently in Kosovo’s capital city of Prishtina. The modernization of Prishtina was initiated with the destruction of the Ottoman-era bazaar (čaršija) at the center of the city: in 1947, the provincial government expropriated the buildings in the bazaar in the name of urban renewal and then demolished them.... Laid out in the fifteenth century, Prishtina’s bazaar was composed of some two hundred shops arranged around a mosque (xhami in Albanian, džamija in Serbian); these shops were owned by and operated by members of Prishtina’s Albanian community. The shops were set within blocks, each devoted to a particular guild or craft.... Like other public works at the time in Yugoslavia, the destruction of Prishtina’s bazaar was organized by labor brigades called Popular Fronts (Fronti populluer in Albanian, Narodnifront in Serbian)."

- SHUJAKU, Valbona (2011). Prishtina Poetic Memories. Kosovo: Re: public. p. 4. ISBN 9789951882408. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

External links

- Municipality of Prishtina https://web.archive.org/web/20130106030233/http://kk.rks-gov.net/prishtina/City-guide/City-Map-(1)/Prishtina-e-vjeter.aspx

- Prishtina Poetic Memories https://web.archive.org/web/20140306053337/http://prishtinapoeticmemories.com/indexsh.html