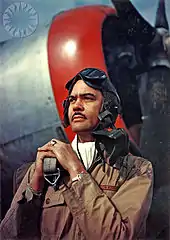

Benjamin O. Davis Jr.

Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr. (December 18, 1912 – July 4, 2002) was a United States Air Force general and commander of the World War II Tuskegee Airmen.

Benjamin O. Davis Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 18, 1912 Washington, D.C., United States |

| Died | July 4, 2002 (aged 89) Washington, D.C., United States |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1936–1970 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 99th Pursuit Squadron 332nd Fighter Group Tuskegee Airmen 51st Fighter Wing Thirteenth Air Force |

| Battles/wars | World War II Korean War Second Taiwan Strait Crisis Vietnam War |

| Awards | Air Force Distinguished Service Medal Army Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star Legion of Merit Distinguished Flying Cross Air Medal Army Commendation Medal Langley Gold Medal |

| Other work | Federal Sky Marshal Program Assistant Secretary of Transportation |

He was the first Black Brigadier general in the United States Air Force. On December 9, 1998, he was advanced to four-star general by President Bill Clinton. During World War II, Davis was commander of the 99th Fighter Squadron and the 332nd Fighter Group, which escorted bombers on air combat missions over Europe. Davis flew sixty missions in P-39, Curtiss P-40, P-47 and P-51 Mustang fighters. Davis followed in his father's footsteps in breaking racial barriers, as Benjamin O. Davis Sr. was the first Black general in the United States Army.

Biography

Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr. was born in Washington, D.C. on December 18, 1912, the second of three children born to Benjamin O. Davis Sr. and Elnora Dickerson Davis. His father was a U.S. Army officer, and at the time he was stationed in Wyoming serving as a lieutenant with an all-white cavalry unit. Benjamin O. Davis Sr. served 41 years before he was promoted to brigadier general in October 1940. Elnora Davis died from complications after giving birth to their third child (Elnora) in 1916. At the age of 13, in the summer of 1926, the younger Davis went for a flight with a barnstorming pilot at Bolling Field in Washington, D.C. The experience led to his determination to become a pilot himself.

After attending the University of Chicago, he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York in 1932. He was sponsored by Representative Oscar De Priest (R-IL) of Chicago, at the time, the only black member of Congress. During the four years of his Academy term, Davis was racially isolated by his White classmates, few of whom spoke to him outside the line of duty. He never had a roommate. He ate by himself. His classmates hoped that this would drive him out of the Academy. The "silent treatment" had the opposite effect. It made Davis more determined to graduate. Nevertheless, he earned the respect of his classmates, as evidenced by the biographical note beneath his picture in the 1936 yearbook, the Howitzer:

The courage, tenacity, and intelligence with which he conquered a problem incomparably more difficult than plebe year won for him the sincere admiration of his classmates, and his single-minded determination to continue in his chosen career cannot fail to inspire respect wherever fortune may lead him.[1]

He graduated in 1936, 35th in a class of 276. He was the academy's fourth black graduate after Henry Ossian Flipper (1877), John Hanks Alexander (1887), and Charles Young (1889). When he was commissioned as a second lieutenant, the Army had only two black officers who weren't chaplains – Benjamin O. Davis Sr. and Benjamin O. Davis Jr.[2] After graduation he married Agatha Scott.

At the start of his junior year at West Point, Davis had applied for the Army Air Corps but was rejected because it did not accept blacks. He was instead assigned to the all-black 24th Infantry Regiment (one of the original Buffalo Soldier regiments) at Fort Benning, Georgia. He was not allowed inside the base officers' club.

He later attended the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning, and then was assigned to teach military tactics at Tuskegee Institute, a historically black college in Tuskegee, Alabama. This was something his father had done years before, as a way for the Army to avoid having a black officer in command of white soldiers.

Early in 1941, the Roosevelt administration, in response to public pressure for greater black participation in the military as war approached, ordered the War Department to create a black flying unit. Captain Davis was assigned to the first training class at Tuskegee Army Air Field (hence the name Tuskegee Airmen), and in March 1942 earned his wings as one of five black officers to complete the course. He was the first black officer to solo an Army Air Corps aircraft.

In July that year, having been promoted to lieutenant colonel, he was named commander of the first all-black air unit, the 99th Pursuit Squadron.

The squadron, equipped with Curtiss P-40 fighters, was sent to Tunisia in North Africa in the spring of 1943. On June 2, they saw combat for the first time in a dive-bombing mission against the German-held island of Pantelleria as part of Operation Corkscrew.[3] The squadron later supported the Allied invasion of Sicily.

In September 1943, Davis was deployed to the United States to take command of the 332nd Fighter Group, a larger all-black unit preparing to go overseas. Soon after his arrival, there was an attempt to stop the use of black pilots in combat. Senior officers in the Army Air Forces recommended to the Army chief of staff, General George Marshall, that the 99th (Davis's old unit) be removed from combat operations as it had performed poorly. This infuriated Davis as he had never been told of any deficiencies with the unit. He held a news conference at The Pentagon to defend his men and then presented his case to a War Department committee studying the use of black servicemen.

Marshall ordered an inquiry but allowed the 99th to continue fighting in the meantime. The inquiry eventually reported that the 99th's performance was comparable to other air units, but any questions about the squadron's fitness were answered in January 1944 when its pilots shot down 12 German planes in two days while protecting the Anzio beachhead.

Colonel Davis and his 332d Fighter Group arrived in Italy soon after that. The four-squadron group, which was called the Red Tails for the distinctive markings of its planes, were based at Ramitelli Airfield and flew many missions deep into German territory. By summer 1944 the Group had transitioned to P-47 Thunderbolts. In the summer of 1945, Davis took over the all-black 477th Bombardment Group, which was stationed at Godman Field, Kentucky.

During the war, the airmen commanded by Davis had compiled an outstanding record in combat against the Luftwaffe. They flew more than 15,000 sorties, shot down 112 enemy planes, and destroyed or damaged 273 on the ground at a cost of 66 of their own planes and losing only about twenty-five bombers. Davis himself led dozens of missions in P-47 Thunderbolts and P-51 Mustangs. He received the Silver Star for a strafing run into Austria and the Distinguished Flying Cross for a bomber-escort mission to Munich on June 9, 1944.

.jpg.webp)

In July 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 ordering the racial integration of the armed forces. Colonel Davis helped draft the Air Force plan for implementing this order. The Air Force was the first of the services to integrate fully.

Davis attended Air War College, served at the Pentagon and in overseas posts over the next two decades. Noteworthy is that during his time at the Pentagon, he drafted the staffing package and gained approval to create the Air Force Thunderbird flight demonstration team.[4] He again saw combat in 1953 when he assumed command of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing (51 FIW) and flew an F-86 Sabre in Korea. He served as director of operations and training at Far East Air Forces Headquarters, Tokyo, from 1954 until 1955, when he assumed the position of vice commander of Thirteenth Air Force (13 AF), with additional duty as commander of Air Task Force 13 (Provisional), Taipei, Taiwan. During his time in Tokyo, he was temporarily promoted to the rank of brigadier general.

In April 1957 General Davis arrived at Ramstein Air Base, Germany, as chief of staff of Twelfth Air Force (12 AF), U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE). When the Twelfth Air Force was transferred to James Connally Air Force Base, Texas in December 1957, he assumed new duties as deputy chief of staff for operations, Headquarters U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), Wiesbaden Air Base, Germany. While in Germany he was temporarily promoted to major general in 1959, and his promotion to brigadier general was made permanent in 1960.

In July 1961, he returned to the United States and Headquarters U.S. Air Force, where he served as the director of manpower and organization, deputy chief of staff for programs and requirements, having his promotion to major general made permanent early the next year; and in February 1965 he was assigned as assistant deputy chief of staff, programs and requirements. He remained in that position until his assignment as chief of staff for the United Nations Command and U.S. Forces in Korea (USFK) in April 1965, at which time he was promoted to lieutenant general. He assumed command of the Thirteenth Air Force (13 AF) at Clark Air Base in the Republic of the Philippines in August 1967.

Davis was assigned as deputy commander in chief, U.S. Strike Command, with headquarters at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, in August 1968, with additional duty as commander in chief, Middle-East, Southern Asia and Africa. He retired from active military service on February 1, 1970. On December 9, 1998, Davis Jr. was promoted to general, U.S. Air Force (retired), with President Bill Clinton pinning on his four-star insignia.[5] In the late 1980s he began to work on his autobiography, Benjamin O. Davis Jr.: American: An Autobiography.

Dates of rank

General Davis' effective dates of promotion are:[5]

| Second Lieutenant, June 12, 1936 | |

| First Lieutenant, June 19, 1939 | |

| Captain, October 9, 1940 (temporary); June 12, 1946 (permanent) | |

| Major, May 13, 1942 (temporary); | |

| Lieutenant colonel, May 29, 1942 (temporary); July 2, 1948 (permanent) | |

| Colonel, May 29, 1944 (temporary); July 27, 1950 (permanent) | |

| Brigadier General, October 27, 1954 (temporary); May 16, 1960 (permanent) | |

| Major General, June 30, 1959 (temporary); January 30, 1962 (permanent) | |

| Lieutenant General, April 30, 1965 | |

| General, December 9, 1998 (retired list) |

Decorations and honors

At the time of Davis's retirement, he held the rank of lieutenant general, but on December 9, 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded him a fourth star, raising him to the rank of full general. After retirement, he headed the federal sky marshal program, and in 1971 was named Assistant Secretary of Transportation for Environment, Safety, and Consumer Affairs. Overseeing the development of airport security and highway safety, Davis was one of the chief proponents of the 55 mile per hour speed limit enacted nationwide by the U.S. government in 1974 to save gasoline and lives. He retired from the Department of Transportation in 1975, and in 1978 served on the American Battle Monuments Commission, on which his father had served decades before. In 1991, he published his autobiography, Benjamin O. Davis Jr.: American (Smithsonian Institution Press). He is a 1992 recipient of the Langley Gold Medal from the Smithsonian Institution.

Military Decorations

His military decorations included:[5]

The Air Force Distinguished Service Medal

The Air Force Distinguished Service Medal The Army Distinguished Service Medal

The Army Distinguished Service Medal The Silver Star

The Silver Star The Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters

The Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters The Distinguished Flying Cross

The Distinguished Flying Cross The Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters

The Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters The Army Commendation Medal with two oak leaf clusters

The Army Commendation Medal with two oak leaf clusters The Philippine Legion of Honor

The Philippine Legion of Honor- The 1992 Langley Gold Medal

- The 2007 Congressional Gold Medal

Face and obverse of the 1913 Langley Medal awarded to Glenn Hammond Curtiss

Face and obverse of the 1913 Langley Medal awarded to Glenn Hammond Curtiss

Honors

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Davis on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[6]

- Benjamin O. Davis Jr Aerospace Technical High School Detroit, Michigan, and Benjamin O. Davis Jr. Middle School in Compton, California, as well as the former Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Aviation High School in Cleveland, Ohio, are all named in his honor. Benjamin O. Davis High School of the Aldine Independent School District in Houston, Texas, opened in 2012.[7]

- The Benjamin O. Davis Jr. Award is presented to senior members of the Civil Air Patrol – United States Air Force Auxiliary who successfully complete the second level of professional development, complete the technical training required for the Leadership Award, and attend Squadron Leadership School, designed "to enhance a senior member's performance at the squadron level and to increase understanding of the basic function of a squadron and how to improve squadron operations."[8][9][10]

- In 2015, West Point named a newly constructed barracks after him.[11]

- He was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum in 1996.[12]

- On 1 November 2019, the airfield at the United States Air Force Academy, in Colorado Springs, Colorado was re-named Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. Airfield.[13]

Death

Davis's wife Agatha died on March 10, 2002.[14] Davis, who had been suffering from Alzheimer's disease, died at age 89 on July 4, 2002 at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. He was interred with Agatha on July 17, at Arlington National Cemetery.[15] A Red Tail P-51 Mustang, similar to the one he had flown in World War II, flew overhead during his funeral service. Bill Clinton said, "General Davis is here today as proof that a person can overcome adversity and discrimination, achieve great things, turn skeptics into believers; and through example and perseverance, one person can bring truly amazing change".

See also

References

- Holbert, Tim G.W. (Summer 2003). "A Tradition of Sacrifice: African-American Service in World War II". World War II Chronicles. World War II Veterans CommitteeIikiii Iiiii (XXI). Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- Lee, Ulysses. The Employment of Negro Troops (PDF). Center of Military History. p. 50. ISBN 9780160429514. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- Moye, J. Todd (2010). Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780199741885.

- "AIR FORCE HISTORY: Gen. Benjamin O. Davis Jr". Tinker Air Force Base.

- "General Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr". Biographies. United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 2004-02-10.

- Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

- "District's newest high school, ninth grade school to be named after General Benjamin Oliver Davis Jr." Archived June 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2014-07-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "General Benjamin O. Davis Jr. Award". Capnhq.custhelp.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-07. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- "Civil Air Patrol – Benjamin O. Davis Jr. Award Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine: Fact Sheet".

- Hill, Michael, "West Point names barracks for black graduate who was shunned Archived May 13, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Associated Press, 10 May 2015

- "San Diego Air & Space Museum - Historical Balboa Park, San Diego". Sandiegoairandspace.org. 2017-10-01. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- https://www.usafa.org/News/DavisAirfield. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Davis, Agatha Scott". Washington Post.

- Burial Detail: Davis, Benjamin O (Section 2, Grave E-311-RH) – ANC Explorer

Further reading

- Applegate, Katherine. The Story of Two American Generals Benjamin O. Davis Jr. and Colin L. Powell, Gareth Stevens Pub., 1995

- Sandler, Stanley. Segregated Skies: All-Black Combat Squadrons of WW II, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benjamin O. Davis, Jr.. |