Berber kings of Roman-era Tunisia

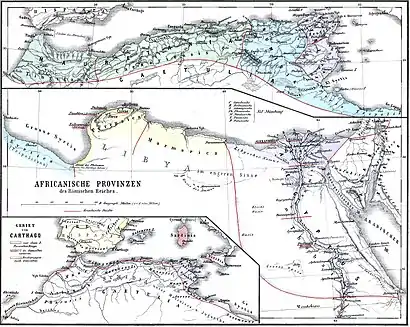

For nearly 250 years, Berber kings of the 'House of Masinissa' ruled in Numidia, which included much of Tunisia, and later in adjacent regions, first as sovereigns allied with Rome and then eventually as Roman clients. This period commenced with the defeat of Carthage by the Roman Army, assisted by Berber cavalry led by Masinissa at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, and it lasted until the year 40 AD, during the reign of the Roman Emperor Gaius, also known as Caligula (37–41 AD).

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Tunisia |

|

|

|

During the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) Rome entered into an alliance with Masinissa, the son of a Berber tribal leader. Masinissa had been driven out of his ancestral realm by a Carthage-backed Berber rival. Following the Roman victory at Zama, Masinissa (r. 202–148 BC) was celebrated as a "friend of the Roman people". He became king of Numidia and ruled for over fifty years. For seven generations his line of kings continued its relationship with an increasingly powerful Roman state.

During this era, the Berbers ruled over many cities as well as extensive land, and the peoples under their governance prospered. Municipal and civic affairs were organized using a combination of Punic and Berber political traditions. One descendant king, a grandson of Masinissa, Jugurtha (r. 118–105 BC), successfully attacked his cousin kings, who were also allies of Rome, and in the course of a long struggle he became an enemy of Rome. In the Roman civil wars after the fall of the Roman Republic (44 BC), Berber kings were courted by the contending political factions for their military support. Berber kings continued to reign, but had become merely clients of Imperial Rome.

One such Berber king married the daughter of Cleopatra of Egypt. He and his son, the last two Berber kings (reigns: 25 BC–40 AD), were not accepted by many of their Berber subjects. During this period, Roman settlers were increasingly taking the traditional pasture lands of transhumant Berber tribes for their own use as farms. The commoner Tacfarinas raised a revolt in defense of Berber land rights and became a great tribal chief as a result of his insurgency (17-24 AD) against Rome.[1][2]

Rome and the Berber kings

In the third and final Punic war (149–146 BC), Roman forces lay siege to the great city of Carthage. When it fell to the Romans the great city had become mostly a burning ruin, and the long rivalry between the two major powers of the western Mediterranean came to an end. Rome annexed Carthage and its immediate vicinity, but the surrounding territories remained in Berber hands, specifically in those of King Masinissa, an ally of Rome. Subsequent independent Berber kings were courted by Rome.

Previously, Carthage had enjoyed fabled wealth through commerce.[3] Accordingly, the Punic city-state had once exerted great economic influence on the surrounding Berber polities and peoples. Yet Carthage directly ruled only an ample territory adjacent to the city and its developed network of trading posts. These Punic enclaves were situated at short intervals along the Mediterranean coast of Africa from Tripolitania westward.[4] Although within a commercial sphere dominated by Carthage, most Berbers lived in territories outside its direct political control.

Comparatively little is known of the most ancient Berber peoples since the few surviving writings from Carthage shed little light on this history, although surviving inscriptions and artifacts do offer some clues and hints. Starting with the Punic Wars, Berbers are, however, mentioned in surviving works of classical Greek and Roman authors and these sources provide some details in the descriptions of Berber events.[5]

During the three Punic Wars, Rome directly entered into permanent relations with the Berber people. In the third war's aftermath, however, Rome turned its attention to the eastern Mediterranean. The fall of the Roman Republic led to the Roman civil wars, whose intermittent military actions and political strife indirectly amplified the significance of the Berber kings. Amid the oscillating demands and shifting fortunes, Berber alliances were sought by rival Roman factions. Berber relations with Rome became multivalent and fluid, characterized variously as a working alliance, functional ambivalence, partisan hostility, veiled maneuvering, and fruitful intercourse. Nevertheless, during these years of Roman civil conflict the political status of the Berber kings continued to erode. From being independent sovereign (Masinissa), the kings had become long-term allies; later their political alliance was required, and eventually they were reduced to Roman clients.[6]

When the last of these civil wars came to an end and the long reign of Augustus (31 BC to 14 AD) commenced, Roman-Berber relations were redefined. Berber kings reigned alongside a triumphant Roman dominion which spanned the entire Mediterranean, and later in 40 AD the last allied Berber kingdom was absorbed by the Empire. Thereafter, probably most Berber peoples lived within the political boundaries of the Roman world.[7]

Nature of the Berber regimes

Circa 220 BC, three large Berber kingdoms had arisen. Markedly influenced by Punic civilization, they had nonetheless endured as separate Berber entities, their culture surviving throughout the long reign of Carthage. West to east these kingdoms were: (1) the Mauri (in modern Morocco) under king Baga; (2) the Masaesyli (in northern Algeria) under Syphax, who then controlled two capitals: to the west Siga (near modern Oran) and to the east Cirta (modern Constantine); and (3) the Massyli (south of Cirta, west and south of nearby Carthage), ruled by Gala [Gaia] (the father of Masinissa). Following the Second Punic War, Massyli and eastern Masaesyli were joined to become Numidia, located in historic Tunisia. Here Masinissa ruled and reigned. Both Rome and the Hellenic states gave Masinissa the honors befitting an admired king.[8]

"Hitherto, the African kingdoms had been temporary tribal coalitions; Masinissa did not wish to be a tribal chieftain, but a true king, with settled subjects, with a proper army and a fleet financed by taxes rather than by irregular and erratic tribal contributions."[9]

Many prosperous cities were governed by the Berbers. A bilingual (Punic and Berber) urban inscription has been found that concerns 2nd-century-BC Numidia. It was excavated from the ancient city of Thugga (modern Dougga, Tunisia), located about 100 kilometers inland from Carthage. The inscription indicates a complex city administration, with the Berber title GLD (cognate to modern Berber Agellid, king or paramount tribal chief) designating the ruling municipal officer. This top position apparently rotated among the selected members of the leading Berber families. Since the Numidian titles of the offices mentioned (GLD, MSSKWI, GZBI, GLDGIML) were not translated into Punic but left in a Berber language, it suggests an indigenous development.[10] These municipal titles were written using letters that represent only the consonant sounds, i.e., without indicating the vowel sounds, a characteristic also of ancient Phoenician and other Semitic scripts, such as Aramaic.[11]

Masinissa and Syphax

The Berber king Masinissa (c. 240–148 BC)[12] was both well known and well regarded in Rome for many decades. He was the first and the most important of the early Berber leaders to establish major relations with the Roman state. His family became, what may be considered, the royal family of Numidia and its vicinity for eight generations: the House of Masinissa.[13] A bilingual inscription (in Punic and Libyan) from the city of Thugga, made a few years after his death, commences:

"The citizens of Thugga have built this temple to king Masinissa, son of the king Gaia, son of the sufete Zilasan, in the year ten of Micipsa." Here the office translated to "king" was written GLD (cognate with modern Berber "agellid" [paramount tribal chief]). The throne came to Masinissa in a roundabout way (from father to uncle to cousin to him). The "sufete" (Hebrew: Shophet) was a Punic title often translated as "judge" as in the biblical Book of Judges, Hebrew being a sister Semitic language to Punic. King Micipsa was the son of Masinissa.[14][15]

Masinissa served as a young cavalry commander for Carthage in Hispania during the early years of the Second Punic War (218–201 BC). There, he met discreetly with the Roman general Scipio and eventually sided with Rome. On the death of his father, King Gala [Gaia], Masinissa sailed home to Massyli, where he fought for the throne against usurpers. A neighboring Berber king Syphax invaded the kingdom, but Masinissa escaped to continue his struggle from the outlying farmlands and mountains. When Scipio's armies later landed in Africa, Masinissa and his cavalry joined them. At the Battle of Zama in 202, Masinissa led Numidian and Italian cavalry on the right wing of the Roman forces. During the battle, his cavalry engaged in fighting disappeared from Scipio's view, but at a crucial moment suddenly reappeared, attacking the Punic forces and gaining victory. Hannibal's defeat here ended the long conflict.[16]

The Roman writer Livy (59 BC – 17 AD) in his history of Rome, Ab urbe condita, devotes a half-dozen pages to Masinissa's character and career, both turbulent and admired, eventful and long in duration.[17] Livy writes: "Since Masinissa was by far the greatest of all the kings of his time and rendered much the most valuable service to Rome, I feel that it is worthwhile to digress a little in order to tell [his] story...."[18] Livy informs us of Masinissa's early military services to Carthage and of his and Carthage's victory over the Masaesyli led by Syphax. Next in Hispania, Masinissa led cavalry units for Carthage against Rome. Here he switched sides to ally with Rome, after meeting with Scipio Africanus, the celebrated Roman general. There followed the death of his father Gala, King of the Massyli, upon which he returned home to find an usurper taking over his father's kingdom. Masinissa then became a guerilla chief in the mountains of Africa, regaining his kingdom after a persistent struggle. Sooner after, Syphax staged an invasion, defeating Masinissa and seizing the Massyli kingdom with Masinissa escaping into the bush. Later, his forces came upon the army of Scipio, recently landed in Africa. The Romans defeated Carthaginian forces in battle and Syphax was captured. Masinissa sends envoys to Rome who meet with the Senate. Carthage was forced to recall Hannibal from Italy to defend the African capital. Nearby, Hannibal fought the Battle of Zama (202 BC) against Scipio's Roman army, with Masinissa at the head of cavalry on Scipio's right flank. Following victory over Hannibal, Masinissa was restored to his kingdom, Massyli along with surrounding Numidia, where he ends up ruling for fifty years.[19]

That the Roman author Livy admired Masinissa is clear from his many favorable comments about the Berber king (constantissima fides). A modern Latin scholar summarizes as follows, citing Livy's Ab urbe condita:

"Masinissa is in fact a foreigner with almost all the Roman virtues. He is religious, for he tells Scipio that he was awaiting any chance to [leave Carthage for Rome] which 'the kindness of the immortal gods offered'. As a general he shows forethought, but also boldness. At Scipio's command, he controls his wayward passions by administering poison to Sophoniba [wife of Syphax]. Above all, his valour is conspicuous; even at age ninety-two, just before the Third Punic War, he leads his army to defeat the Carthaginians. Masinissa is one of Livy's great heroes, and throughout the fourth decade [Livy's books XXX to XL] he is mentioned in speeches as an example to the peoples of the East of all that a king-ally should be. Hasdrubal is made to say: 'There is greater talent of nature and mind in Masinissa that in any previous member of his race.' And Livy calls him 'by far the greatest king of his day'."[20]

Regarding Sophoniba, her story provides a perspective on the rivalry between the two kings, Syphax of Masaesyli (west Numidia) and Masinissa of Massyli (east Numidia).[21] Her story also sheds light on the relationship between Carthage and the Berbers, with particular reference to Rome. Livy (59 BC – 17 AD), the Roman historian, presents a rather detailed portrait of these circumstances, especially events following the defeat of her husband Syphax. Such details may shed light on the personality of Masinissa, or at least on the world in which he lived. Yet ancient historians were not unfamiliar with propaganda and their readers expected them to recreate scenes, giving memorable, probable versions of what might have happened.[22]

Sophoniba was the young and beautiful daughter of Hasdrubal Gisco, a leading general of Carthage. To secure the allegiance of the Berber kingdom of Massyli, she was pledged to Masinissa, but when he turned to Rome she was given instead to his rival, the Berber king Syphax of neighboring Masaesyli, for a similar purpose. Syphax then invaded Massyli, forcing Masinissa to flee. As the Second Punic War neared its climax (which would be at Zama), Scipio landed his Roman armies in Africa, where Masinissa joined him. Syphax was quickly defeated, with Masinissa triumphant.[23] Here Sophoniba's attentions win the affection of Masinissa and his allegiance; he quickly marries her, to present the Romans with a fait accompli. Days later Scipio persuades him that the politics of the Rome–Carthage conflict make his marriage to Sophoniba impossible;[24] she must be taken to Rome. Sophoniba tells Masinissa that the bond between Carthaginian and Berber, both of Africa, is against Rome. Reluctantly accepting that their marriage must end, she pleads with him that she not be humiliated. Masinissa agrees and gives her poison, which she takes.[25][26] Hers may be compared to Dido's suicide 650 years earlier, but there Dido died to avoid marriage to the Mauretani Berber leader Hiarbus. Here, however, Sophoniba married first Syphax, then Masinissa; it was not the Berber husband she refused; she rejected the ordeal of being paraded in a Roman triumph.[27]

A modern historian characterizes Masinissa, noting in particular his "tremendous ideal" of uniting the Berber peoples, which motivated many of his actions during his long reign:

"Masinissa, who was thirty-seven years old at Zama, preserved his vigour into a ripe old age: at eighty-eight he still commanded his army in battle, mounting his horse unaided and riding bareback. But he had other outstanding qualities besides physical vigour. Fearless and unscrupulous, diplomatic and masterful, he conceived the tremendous ideal of welding the native tribes of North Africa into a nation. He successfully developed agriculture and commerce, and encouraged the spread of Punic civilization. His fame soon exceeded the confines of Africa; he cultivated relations with the Greek world, and at Delos at least three statues were erected in his honour. Throughout he remained a faithful ally of Rome...."[28]

The isle of Delos was long famous as a cultural center of Ancient Greece, where its deities and acclaimed mortals were honored. The three statues of Masinissa at Delos mentioned in the above text were erected on behalf of the kingdom of Bithynia in Anatolia, the isle of Rhodes, and the city of Athens. The Numidian king Masinissa was "treated, by the Romans as well as the Carthaginians, with all the honour due to Hellenistic monarchs." "He was a hero on a large scale." "As an established king, [Masinissa] carefully cultivated the image of the perfect Hellenistic monarch through his coinage and the participation of at least one of his sons in the Panathenaic games."[29]

After the Battle of Zama (202 BC), Masinissa became famous and was held in high esteem as a friend of the Roman people. For over fifty years he ruled as King of Numidia (lands west of Carthage) until his death in 148 BC.[30][31] During his reign farming and trade prospered, and the vital pulse of Berber culture quickened. Government institutions were established, evidently having an independent Berber origin, although informed by Punic civil traditions; indeed, Masinissa encouraged the cultural influence of Carthage. "The state, the life of the cites, art, religion, writing—all underwent a rapid process of Punicization."[32] The language used at court was Punic.[29] "He successfully developed agriculture and commerce, and encouraged the spread of Punic civilization."[33]

Masinissa also cultivated a grand vision of uniting all the Berbero-Libyan peoples from the frontiers of Egypt to the Atlantic. His expansionist actions were directed mainly against the surviving city-state of Carthage. Eventually Masinissa's aggressive actions achieved several major acquisitions of lands previously held by Carthage, not only at the borders of Numidia and Carthage, but extending also well south of Punic territory, and including Mediterranean seaports in Tripolitania to the east of Carthage. Indeed, his last war against Carthage turned out to be a prelude to the Third Punic War (149–146 BC). Here, Rome intervened and eventually besieged and destroyed Carthage.[34][35][36]

A not altogether novel view was that "Rome destroyed Carthage to prevent Masinissa from seizing it and becoming a Mediterranean power."[37] Confronting with the Roman siege, Carthage entrusted the defense of the city to Hasdrubal, a grandson of Masinissa. Accordingly, suspicions arose among the Romans about the role of the elderly yet still able king, now in his nineties.

"Masinissa caused slight anxiety. It was a grandson of his that was organizing the defense of Carthage, and the king himself, who saw the fruits of his ambitions now snatched from his grasp, was somewhat cold when asked for assistance; when later he proffered it, he was told abruptly that the Romans would let him know when they needed help."[38]

The ancient Numidian king died during this Third Punic War. The Greek historian Polybius (c. 200–118 BC) praised him highly in his Histories, in a text that might be regarded as an obituary for the celebrated Berber leader:

"Massanissa, the king of the Numidians in Africa, one of the best and most fortunate men of our time, reigned for over sixty years, enjoying excellent health and attaining a great age, for he lived till ninety.... And he could also continue to ride hard by night and day without feeling any the worse. [When] he died, he left a son of four years old... besides nine other sons. Owing to the affectionate terms they were all on he kept his kingdom during his whole life free from all plots and from any taint of domestic discord. But his greatest and most godlike achievement was this. While Numidia had previously been a barren country thought to be naturally incapable of producing crops, he first and alone proved that it was as capable as any other country of bearing all kinds of crops.... It is only proper and just to pay this tribute to his memory on his death."[39]

Yet Polybius continues: "Scipio arrived in Cirta two days after the king's death and set everything in order." This closing remark might be interpreted as a sign of the great affection and care given this long-term friend of Rome, or merely as an important Roman politician-soldier's prudent attention to state interests after the death of an important ally in time of war, or both. Livy gives the Roman view of the king's character when he imagines Hasdrubal saying of the young Numidian: "Masinissa was a man of far loftier spirit and far greater ability than had ever been seen in anyone of his nation....he had often given evidence to friends and enemies alike of a valour rare amongst men."[40]

Micipsa, Jugurtha, Hiempsal

Micipsa, Mastanabal, and Gulussa were Masinissa's three sons, among whom he divided his kingdom of Numidia, but only Micipsa survived; his two brothers soon fell victim to disease. Micipsa's reign lasted thirty years (148-118 BC). He continued the alliance with Rome, during which Numidia enjoyed relative peace and prosperity. His two sons, Adherbal and Hiempsal, were raised to assume the throne, but when they were still young their older cousin Jugurtha, Mastanabal's illegitimate son, joined the household. Jugurtha's evident talents were a cause of concern to Micipsa, who accordingly sent him to Hispania to serve the Romans in their war against Numantia, which ended in 133 BC. As a warrior Jugurtha performed very well, winning great favor among the Roman commanders, one of whom, Scipio Aemilianus, wrote a favorable letter to Micipsa. Upon his return Micipsa adopted Jugurtha and made him co-heir with his own two young sons. Sallust's rendering of Scipio's letter:

"Your nephew Jugurtha has distinguished himself in the Numantine War above everyone else, which I'm sure will give you pleasure. I hold him in affection for his services and will do all I can to make him equally esteemed by the Roman Senate and People. As your friend I congratulate you personally; you have in him a man worthy of yourself and of his grandfather Masinissa."[41]

At Micipsa's death in 118, the three became rulers of adjacent lands carved out of Numidia. Yet Jugurtha's suspicions were soon aroused. He had Hiempsal killed; then defeated Adherbal in battle. Rome intervened and, due to bribes paid by Jugurtha, merely caused the lands to be redivided. Eventually Jugurtha again attacked Adherbal, besieging him in the city of Cirta. Rome again sent its agents to broker a settlement. But in 112 Jugurtha accepted the city's terms of surrender; nonetheless Adherbal was tortured and killed, and Italian traders were slaughtered. Jugurtha then became king of all Numidia.[42] Whether or not he intended to "unite all the Berbers in a patriotic war" following the vision of Masinissa (see above) is uncertain.[43]

To the west of Numidia was the Berber Kingdom of Mauretania (in modern Algeria), under the reign of Bocchus I. Jugurtha married his daughter. Farther west, Tingis (modern Tangier) was the capital of another Berber realm comprising western Mauretania, under its king, Bogud, brother of Bocchus I. To the south of Numidia and Mauritania and Africa Province lay the lands of the Berber Gaetulians, who were not politically united. On these lands Berber pastoralist managed their flocks, and in lean years would naturally seek better pasturage. A major advantage sought by Rome in its Numidian alliance was leverage in dealing with these other Berbers, in order to maintain the peace.[44] "[T]he policy of Rome appears to have been to co-opt the tribal leaders, and through them to control the tribes."[45]

Africa Province became the scene of military actions involving key Roman leaders toward the end of the Roman Republic (c.510–44 BC). Here Numidia played a significant role. That "a political and military importance was given to this state, such as no other client-state of Rome ever possessed... is shown by the share of Numidia in the civil wars of Rome."[46] This appears to follow Livy's assessment of Masinissa given above. A modern Maghribi historian puts it differently: "The Berber princes let themselves be drawn into alliances with the leaders of the warring Roman factions."[47] As a side result, Roman soldiers came to know first-hand the fertile agricultural lands of the Province, where many would arrange to retire as veterans.

Jugurtha (r.118–105 BC), the Berber king of Numidia (to the west of the Province) and grandson of the revered king Masinissa (r. 202–148 BC), was well known to his Roman allies. In part due to the favors he gave to Roman politicians, Jugurtha had managed to enlarge the scope of his power; yet eventually his dealings resulted in a notorious bribery scandal at Rome. Jugurtha's assassinations of his regal cousins, his military aggression and overreach, and his slaughter of Italian traders at Cirta led to war with Rome.[49]

The war's prosecution involved the hands-on participation of two controversial Roman political and military leaders. Gaius Marius celebrated his triumph due to his success in finishing Rome's long war against Jugurtha. A wealthy novus homo and populares, Marius was the first Roman general to enlist proletari (landless citizens) into his army; as a politician he was chosen Consul an unprecedented seven times (107, 104–100, 86), but his career ended badly. On the opposing side politically, the optimate Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix, later Consul (88, 80), and Dictator (82–79), had served as quaestor under Marius in Numidia. In 106 Sulla had persuaded Bocchus I of Mauritania to hand over Jurgurtha, which ended the war. This conflict was later (c. 40 BC) described by the ancient Roman political writer Sallust (86–35), in his well-known monograph Belum Jugurthinum.[50][51]

Thereafter Hiempsal II (r. 106–60), a nephew of Jugurtha, became king of Numidia.[52] During an armed phase of political-economic struggle for Rome between populares led by Marius and optimates under Sulla, Hiempsal II apparently favored the aristocratic Sulla. In 88 BC after Sulla's army entered Rome nearly unopposed, the aging Marius was forced to flee to Africa to seek asylum. King Hiempsal welcomed Marius, but decided to hold his guest prisoner. Marius sensed the danger and effected his escape.[53]

Later Hiempsal lost his crown for several years. The populares being led by Marius and Cinna, allies of Cinna deposed Hiempsal favor of "a Numidian pretender named Iarbus". But Cinna was killed, and a shift in the Roman struggle favored the optimate Sulla, who emerged victorious in November of 82. Marius committed suicide, and Sulla sent the young Pompey to Numidia to restore Hiempsal to the throne.[54]

Juba, Bocchus, Juba, Ptolemy

Decades later, the Numidian king Juba I (r. 60–46) played a significant role in Rome's civil wars, contested by arms between Pompey and Julius Caesar. Juba I was king by descent, being in the line of the famous Masinissa (240–148), per Mastanabal (king 148–140), via Jugurtha's half-brother Gauda (king, 106–88), by Gauda's son Hiempsal II (king thereafter, 88–62), who was the father of Juba I.[55][56] In 47 BC, Julius Caesar and his forces landed in Africa in pursuit of Pompey's remnant army, which was headquartered at Utica near Carthage. There Caesar's enemies Pompey and Cato enjoyed the support of Juba I.

Juba I had long held a personal animus against Julius Caesar dating back to an incident when Caesar was praetor (62 BC) in Africa; the story is related by the ancient Roman writer Suetonius and regarded King Hiempsal II, father of Juba I. Caesar judged as unfair and oppressive the King's treatment of his noble vassal Masintha and effectively interfered, not without physical altercation between Caesar and Juba I.[57]

Cato 'Uticensis', a praetor in 54 and a political leader of Caesar's optimate opponents. was at Utica with Juba I. Cato was widely admired, but also widely mocked.[58] Caesar's nearby victory at the Battle of Thapsus almost put an end to this Roman civil war. Cato committed suicide by his sword.[59] Juba I, his kingdom lost, also committed suicide.[60][61] Caesar annexed Numidia for Rome.

The Berber kings of Mauretania, Bocchus II of the east (roughly the modern Algerian coast), and his brother Bogud of the west (capital at Tingi, modern Tangier), had both favored Julius Caesar (100–44 BC), whom Juba I had worked to oppose. Both had significantly aided Caesar's campaigns: Bogud fought with Caesar in the second Hispanic War; in Africa, Bocchus II captured the Numidian capital city of Cirta from Juba I. In the final Roman civil war (c. 34–30), the contest lay between Octavius and Marcus Antonius. Bocchus II favored Octavius, Julius Caesar's adopted son, later renowned as Augustus, but Bogud inclined to Antonius. The victory of Augustus cost Bogud his kingdom. Bocchus II remained king, yet before he died, Bochus II willed his kingdom to Rome.[55][62]

Augustus (imperial rule: 31 BC – 14 AD) controlled the Roman state following the civil wars that marked the end of the Republic (c. 510–44 BC). He established a quasi-constitutional regime known as the Principate, commonly included as the first phase of the Empire. Roman actions in Africa throughout the period of civil war are harshly criticized by a modern Maghribi historian, Abdallah Laroui, who notes the cumulative lands lost by Berbers to Romans, and how the Romans had steadily steered events to their benefit.[63]

About 26 BC, the emperor Augustus at Rome moved to "restore" the Berber royal line stemming from Masinissa by installing Juba II (son of the defeated Juba I) on the throne, not as King of Numidia, but of Mauritania (west of Numidia).[64] Captured as a youth by the Romans, Juba II had been raised and educated in proximity to the court of Augustus, who became his personal friend. Juba II was installed in power as a client king of the Empire, an amicus romani ("friend of Rome"). His domain was "an artificial monarchy: imposed by Rome on an area which his family had never governed."[65]

Juba II was also "a Greek man of letters", an able author of books on the culture and history of Africa, including his Libyka (written circa 25–5 BC) on the Berber peoples, and later a popular book on Arabia. Unfortunately, only scattered pieces of these works remain.[66] He married well: Cleopatra Selene II, the daughter of Marcus Antonius, consul (44, 34 BC) and triumvir (43–38, 37–33 BC), and Cleopatra, the Ptolemaic Queen of Egypt; she also had been raised at Rome. Their new capital of Greco-Roman style, Iol Caesarea, was established on the sea coast. Though intended to serve as a buffer between Roman Africa and Berber tribes (both those settled or long accustomed to transhumance within the province, and those south of the frontier), Juba II was never accepted by the more tribal elements among his kingdom's Gaetulian Berbers; many of them not only resisted taxation but also joined an armed, anti-Roman insurgency. Yet Juba II did enjoy a long reign (r. 25 BC – 23 AD) under Roman sponsorship and support.[67][68][69]

The unpopular reign of his son Ptolemy [Ptolemaeus] (r.23–40 AD) provoked an increase in Berber support for the rebel forces of Tacfarinas (see below). Ptolemy himself assisted the armies of the Roman governor of Numidia against this wide-scale insurgency (17–24 AD).[70] Later, in 40 AD on a visit to Rome, Ptolemy was assassinated by order of the notorious Emperor Caligula. Following his death, the Gaetulians of Mauritania rebelled, which Rome eventually quelled. Ptolemy's kingdom and other lands to the west were annexed by the Empire as the Provinces of Mauritania Caesaria (approximately the central and western coast of modern Algeria), and Mauritania Tingitana (northern Morocco).[71][72] Thus ended, in its seventh generation, the royal line of Masinissa.

Tacfarinas and the land

Tacfarinas was not born a king or into a royal or a noble bloodline, but a Berber commoner who fought against the Roman Empire in order to maintain tribal grazing rights to land. As a result, he became the tribal chief of his people, the Musulamii. Eventually he led a large tribal confederacy, with assistance from neighboring Berber kingdoms, which for many years sustained a major conflict against Rome.[73]

Events of the insurgency of Tacfarinas, which persisted during the years 17 to 24, and of the Roman campaign against him, appear in the well-known Annals of the Roman historian Tacitus (c.55–c.117).[74] Parallels have been drawn to a previous Roman campaign in Numidia against the Berber king Jugurtha (r. 118–105),[75] recorded by the Roman historian Sallust.[76] It has been long alleged that both historians allow ancient Roman political concerns to distort and obscure the reality of the Berber situation and the Berber leaders.[77]

Tacfarinas, as a commoner of Numidia, served for a time in the Roman Army occupying its imperial Africa Province, but he later deserted. His loyalty lay with his tribe the Musulamii, pastoralists who practiced transhumance, i.e., wintering their herds in the dryer south, but in summer moving their livestock herds northward to better-watered lands.[78]

Throughout the Empire news of the fertile soils of Africa eventually spread, which was an invitation to people looking for agricultural opportunities. Accordingly, many ordinary Italians and various peoples of the Empire immigrated there to work and live; the wealthy sent agents with investment funds to purchase and manage the land; those with political influence might have been similarly favored. Ownership of public land was considered Roman by right of conquest; for local private real estate, citizens had to pay the Roman stipendium tax.[79][80]

Lands of the north, formerly open to summer seasonal grazing, began to be taken and transformed into farms. Hence in late spring tribes of pastoral Berbers arrived at what they considered their customary grazing lands, only to be told that the land was now entirely owned by another, a planter, who refused them permission to graze and water their herds. The new, often large, agricultural operations produced grain for export, which quickly became highly profitable. The two opposing sides were firmly committed to their own interests.[81][82][83]

In the countryside Tacfarinas raised and led an armed revolt. At first the Romans dismissed him as a bandit. Using Roman methods, Tacfarinas trained the tribal warriors into military formations, and his initial success made him tribal chief. Other Berber tribes from Numidia and Mauretania joined him. The Roman Army, tasked to defeat him, offered battle. Tacfarinas accepted, but was routed. The next year Tacfarinas began attacking and looting the new settlers and villages, as told in the account given by Tacitus. Then the insurgents surrounded a Roman regular battalion, who abandoned its commander yet survived the battle, though disgraced; this battalion was later decimated as punishment by the Roman governor. Grown wealthy with loot, Tacfarinas set up a permanent base, where he was attacked and defeated by the Romans, but he escaped into the desert.[84]

Tacfarinas raised new forces from the countryside, but also offered to negotiate land for peace. "The Numidian leader took up arms to force the all-powerful emperor to recognize his people's right to land."[85][86] The Emperor Tiberius was furious at this no-account commoner, who by offering terms acted like a king. Instead, the Romans offered pardon to rebels who surrendered and also set up counter-insurgency style operations, with many strategic forts and small armed patrols, which checked the rebels for a while. Tiberius, misperceiving the situation, awarded the Roman commander a victory triumph in the year 22. Nonetheless, Tacfarinas renewed the fight as strong as ever. He led the forces of his tribe, together with allies from Numidia and Mauretania, with additional assistance from the Berber Garamentes. Tacfarinas also spread persuasive anti-Roman propaganda. In the year 24, however, following field intelligence, Roman forces surprised the secret camp of Tacfarinas, who died fighting.[87][88] In the south of Africa Province, smaller-scale Berber insurgencies continued, off and on, hot and cold, for centuries.[89][90]

See also

References

- For the geography of Tunisia and other background, see History of Tunisia.

- For reference sources, see the footnoted sections that follow.

- Theodor Mommsen writes of the ancient city-state: "From a financial point of view, Carthage held in every respect the first place among the states of antiquity.... Polybius calls it the wealthiest city in the world." Romische Geschicht (Leipzig 1854–1856) at Bk. III, Ch. I, [Par. 22]; translated as The History of Rome (London 1864; reprint London: Dent 1911) at II: 17–18.

- Carthage had also directly ruled in various Mediterranean islands and in lands of Hispania, but these were already lost as a result of the Second Punic War.

- Cf. Abdallah Lauroui, in his L'Histoire du Maghreb: Un essai de synthèse (Paris: Librairie François Maspero 1970), translated as The History of the Maghreb. An Interpretive Essay (Princeton University 1977), 30.

- Berber leaders are called "princes". E.g., Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970; Princeton Univ. 1977), 30.

- Cf. Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (1971), 30–36.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), 24–27 (kingdoms).

- Susan Raven, Rome in Africa (London: Evans Brothers 1969; new ed., London: Longman 1984), 47.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), 37–40 (Berber urban offices).

- Subsequently, Hebrew and Arabic indicate the vowel sounds by the addition of "diacritical points" usually placed above the letters. Isaac Taylor, The Alphabet. An account of the origin and development of letters (London 1883, reprint Madras 1991) at I: 159–161.

- Livy (59-A.D.17), Ab urbe condita at XXIV, 48; Books XXI-XXX translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt, edited by Betty Radice, as The War with Hannibal (Penguin 1965, 1972) at 290. Here the modern edition's footnote makes Masinissa ten years older than his age in Livy's text, giving him a birth date circa 240.

- Masinissa is discussed by Mouloud Gaid in his Aguellids et Romains en Berberie (Alger: Sned 1962; 2d ed. Alger: Opu 1985). Gaid (at 24) provides a diagram including the Kings of Numidia, which may also be called the "House of Masinissa":

- Kings of Numidia (with dates of reign) {relation (to Masinissa by default)}, and events [sources]

- Zilassan {grandfather}, not yet King of Numidia, but a local Sufete [Brett & Fentress (1996), 39]

- Gaï (died 208) {father}, King of Numidia [Brett & Fentress (1996), 39]

- Ousalces (died 207) {uncle (brother to Gaï)}, [Brett & Fentress (1996), 289, n70 (text on p. 48)]

- Capusca (r. 207–207) {cousin (son of Ousalces)}, [Brett & Fentress (1996), 289, n70 (text on p. 48)]

- Lacumaces (r. 207–202) {cousin}, under regency of Mazaetullus, rival to Gaï (mostly ruled by his rival Syphax) [Livy, XXIX, 29–32]

- Masinissa (r. 202–148), King of Massyli & Masaesyli (see Syphax below) [Ilevbare, Carthage, Rome & the Berbers (1980), 175]

- Micipsa (r. 148–118) {son}, [Sallust, 5-6]

- Gulussa (r. 148–c.140) {son}, died of disease [Sallust, 5–6]

- Mastanabel (r. 148–c.140) {son}, died of disease [Sallust, 5–6]

- (Misagènes, Masgaba, Stembanos {other sons}; Asdrubal {daughter})

- Hasdrubal the Boeotarch (c. 149) {grandson}, commander of Carthage during Roman siege [Scullard (1935, 1991), 311]

- Adherbal (r. 118–112) {grandson (by Micipsa)}, killed at Cirta by Jugurtha [Sallust, 5–6, & 25]

- Hiempsal I (r. 118–116) {grandson (by Micipsa)}, killed at Thirmida by Jugurtha [Sallust, 5–6, & 13]

- Jugurtha (r. 118–105) {illegitimate grandson (by Mastanabel)}, [Sallust, 5–6]

- Massiva (died 110) {grandson (by Gulussa)}, killed at Rome by Jugurtha, as potential rival [Sallust, 35]

- Gauda (r. 105) = {grandson (by Mastanabal, half-brother to Jugurtha)} [Sallust, 65]

- Oxynta

- Hiempsal II (r. 106–60) {great-grandson (by Gauda via Mastanabal)}, deposed by Hiarbas (82-80), restored by Pompey (80) [Brett & Fentress (1996), 43] [Ilevbare (1980), 175]

- Juba I (r. 60–46) {great-grandson (by Hiempsal II)}, defeated in Roman civil war at Battle of Thapsus in 46, Numidia in 46 being annexed to Rome by Julius Caesar [B&F (1996), 43]

- Kings of Western Massyli and Masaesyli ("western Numidia")

- Kings of Mauretania (west of Numidia)

- Baga (during Second Punic War (218–201)) {evidently not related to Masinissa} [Ilevbare, Carthage, Rome & the Berbers (1980), 175]

- Bocchus I (circa 105 [118–81]) {father-in-law to Jugurtha, evidently not related to Masinissa} [Sallust, 81] [B&F on p. 42] [Ilevbare, 175]

- Bogud I (80–50, of western Mauretania) {brother of Bocchus I, evidently not related to Masinissa} [Ilevbare (1980), 175]

- Bocchus (Sosus) (80–50, of Eastern Mauretania) {evidently not related to Masinissa} [Ilevbare (1980), 175]

- Bogud II (50–38, of Western Mauretania) {evidently not related to Masinissa} [Ilevbare (1980), 175]

- Bocchus II (50–33) {evidently not related to Masinissa} died c.33, willed his kingdom to Rome [Brett & Fentress (1996), 43]

- Juba II (r. 25 BC – 23 AD) {great, great great-grandson (by Juba I)} installed by Augustus as client king of Rome [B&F (1996) 43]

- Ptolemy (r. 23–40) {great, great, great great-grandson (by Juba II)} unpopular, killed by Caligula [Brett & Fentress (1996), 43, 47]

- (Mauretania was annexed by Rome in A.D. 40, and made a Roman Province in 43)

- Kings of Numidia (with dates of reign) {relation (to Masinissa by default)}, and events [sources]

- Michael Brett and Elizabeth Fentress, The Berbers (Oxford: Blackwell 1996), 39. Regarding Berber laws of succession, Brett and Fentress remark: "The original rule may have been that the eldest agnate succeeded: at the death of Masinissa's father, Gaia, the kingdom passed to Gaia's brother, Oezalces, and from him to his son, Capussa, who died in combat. Only then did it return to Gaia's line." That is, to Masinissa. Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), 289, note 70 (text on 48).

- This inscription is also discussed at Accounts of the Berbers in the article Early History of Tunisia.

- H. H. Scullard, A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC (London: Methuen 1935, 4th ed. 1980; reprint: Routledge, London 1991), 237.

- Livy, his Ab urbe condita [History of Rome from its Foundation] at XXIX, 29–34; Books XXI–XXX translated as The War with Hannibal (Peguin 1965, 1972), 604–612 (digression).

- Livy, Ab urbe condita at XXIX, 29; translated as The War with Hannibal (Penguin 1965, 1972), p. 604.

- Livy, The War with Hannibal (Penguin 1965, 1972), 290–291, 340 (with Carthage against Syphax, and against Rome in Spain), 455 (his nephew captured and released by Scipio), 519, 543–545 (Masinissa and Scipio), 604–612 (from his father's death to Scipio's early victory), 632, 640 (Syphax captured, the Roman Senate), 661–663 (the Battle of Zama).

- P. G. Walsh, Livy. His Historical Aims and Methods (Cambridge University 1961; reprint: Bristol Classical Press 1989), 87.

- The ancient names of these two regions may simply refer to the west and the east of Numidia. Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (Oxford: Blackwell 1996), 26.

- Cf. P. G. Walsh, Livy. His Historical Aims and Methods (Cambridge University 1961; reprint: Bristol Classical Press 1989), chapter II "The traditions of ancient historiography", 20–45.

- This occurs before the decisive Battle of Zama, where Scipio with Masinissa will defeat Hannibal.

- Here, an oblique reference to Homer's poem the Iliad may be suggested, to the dispute between Achilles and Agamemnon over the young woman Briseis. Homer, The Iliad, Book I, in translation by E. V. Rieu (Penguin 1950), 23–39.

- Livy (59 BC – 17 AD), his Ab urbe condita [History of Rome from its Foundation] at XXX, 12–15, also XXIX, 29–34, and XXX, 8–16; Books XXI–XXX translated as The War with Hannibal (Peguin 1965, 1972), 633–637, also 604–612, and 626–638.

- Cf. Polybius (c.200–118), The Histories XIV, 1 & 7, translated in part as The Rise of the Roman Empire (Penguin Books 1979), 452 and 461.

- Cf. Soren, Khadar, Slim, Carthage (1990), 18–19, 28, 120, 242.

- H. H. Scullard, A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC (London: Methuen 1935, 4th ed. 1980; reprint: Routledge, London 1991), 307.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (Oxford: Blackwell 1996), 27.

- S. A. Handford, "Introduction", 29, to his translation of Sallust, The Jugurthine War (Penguin 1963).

- Following Zama (202) Rome allowed Masinissa rule over Numidia, i.e., to take the lands of the defeated Berber king Syphax and to recover any other lands Masinissa or his ancestors had once possessed. H. H. Scullard, A History of the Roman World. 753 to 146 BC (London: Methuen 1935, 4th ed. 1980; reprint: Routledge, London 1991), 307–308.

- Abdallah Laroui, L'Histoire du Maghreb: Un essai de synthèse (Paris: Librairie François Maspero 1970), translated as The History of the Maghrib. An Interpretive Essay (Princeton University 1977), 52.

- Scullard, A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC (1935, 4th ed. 1980; 1991), 307.

- Jamil M. Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (Cambridge University 1971), 28,29.

- Scullard, A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC (1935, 1980, 1991), 307,308.

- H. L. Havell, Republican Rome (London: George G. Harrap 1914; reprint: Oracle 1996), 316–317.

- Laroui, The History of the Maghrib. An Interpretive Essay (Paris 1970; Princeton University 1977), 54.

- Scullard, A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC (1935, 1980, 1991), 311–312.

- Polybius, The Histories, XXXVI, 16, a fragment translated in The Histories of Polybius (Loeb Classical Library 1927), volume VI, 381.

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, XXIX, 31, translated in part as The War with Hannibal (London: Penguin 1965, 1972), 606. This Hasdrubal was the son of Gisco, the father of Sophoniba, and a military leader in Carthage during the Second Punic War; here he was said to be speaking to the Berber King Syphax, Masinissa's early rival.

- Sallust (86–36), Bellum Iugurthinum (late 40s B.C.E.), 5–8, translated as The Jugurthine War (Penguin 1963), 39 (Micipsa's two sons and nephew Jugurtha), 40–42 (Jugurtha in Hispania), 42 (letter quoted, Jugurtha adopted and made heir).

- Sallust, Bellum Iugurthinum, 10–25, translated as The Jugurthine War (Penguin 1963), 44–46 (Micipsa dies, Hiempsal murdered, Adherbal defeated), 47–53 (Adherbal and Jugurtha at Rome, which splits the lands), 57–62 (Jugurtha attacks Adherbal at Cirta, who appeals to Rome again), 62 (Adherbal tortured and killed, Italians at Cirta slaughtered).

- Abdallah Laroui, L'Histoire du Maghreb: Un essai de synthèse (Paris: Librairie François Maspero 1970), translated as The History of the Maghrib. An Interpretive Essay (Princeton University 1977), 30.

- Theodor Mommsen, Römanische Geschichte, volume 5 (Leipzig 1885, 5th ed. 1904), translated as The Provinces of the Roman Empire (London: R. Bentley & Sons 1886; London: Macmillan 1909; reprint: Barnes & Noble 1996), 307.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), 50 and et seq.; also 42 (Bocchus I, father-in-law of Jugurtha).

- Mommsen, The Provinces of the Roman Empire (1885, 1996), 307.

- Abdallah Laroui, L'Histoire du Maghreb: Un essai de synthèse (Paris: Librairie François Maspero 1970), translated as The History of the Maghrib. An Interpretive Essay (Princeton University 1977), 30.

- H. L. Havell, Republican Rome (London: George G. Harrap 1914; reprint: Oracle 1996), 536 and Plate LXIV, coin no. 11.

- Abun-Nasr describes Numidia then as a Roman protectorate. A History of the Maghrib (1971), 30.

- Sallust, Belum Iugurthinum, 113, translated as The Jugurthine War (Penguin 1964), 147–148 (Jugurtha captured and then sent in chains to Rome).

- Abdallah Laroui, in his L'Histoire du Maghreb: Un essai de synthèse (Paris: Librairie François Maspero 1970), translated as The History of the Maghrib. An Interpretive Essay (Princeton University 1977), 30, makes this comment:

"The history of the long war waged by Roman armies is as much the history of the inner contradictions of the Roman republic... as of Jugurtha's revolt. Jugurtha's action may or may not have been a conscious effort to unite all the Berbers in a patriotic war; Sallust's account offers no proof either way, since to him Jugurtha was a mere pretext for airing a moral judgment on Rome and its leaders."

. - Dates of his father's reign are said to start in 106 or 105 and to end the same year, or to end later in 88. Thereafter Hiempsal II became king. Cf. Ilevbare, Carthage, Rome and the Berbers (Ibadan University 1980), 175.

- Plutarch (c.46–120), Bioi Paralleloi [Parallel Lives], translated by John Dryden, revised, as Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (New York: Random House, The Modern Library [no date]), "Caius Marius", 494–525, 520–521.

- H. H. Scullard, From the Gracchi to Nero. A history of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 (London: Methuen 1959; 4th ed. 1976), 72 (Marius flees to Africa), and 80–81 (Sulla's victory; Hiempsal and Iarbus, Pompey).

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), 43.

- Duane W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene (New York: Routledge 2003), 265 ("Numidian royal line").

- Suetonius (69–140), De vita Caesarum per chapter 1, "Julius Caesar", 71; translated by Robert Graves as The Twelve Caesars (Baltimore: Penguin 1957), 39.

- Cato's posthumous title 'Uticensis' refers to the Punic city of Utica, where he died. This Cato was a descendant of the famous Cato the Elder (234–149, Consul 195). Ironically, it was this elder Cato's fanatic hatred of Carthage that spurred Rome to later destroy the Punic city-state (146 BC). Bowder, ed., Who was Who in the Roman World (Cornell Univ. 1980), 52–53.

- H. L. Havel, Republican Rome (London 1914, reprinted 1996), 522–524. Cato Uticensis was a controversial figure, admired by his political faction as a defender of the ancient Republic, but mocked by his opponents as a defender of aristocratic privilege, whose intransigence pushed Rome into civil war. His claim would be as a martyr of republican liberty. Havel (1914, 1996), 524.

- Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970, Princeton University 1977), 30.

- Havel, Republican Rome (1914, 1996), 523. Juba's end was singular. Retreating to a villa after the battle, he and a Roman army veteran both ate well, then—escape being hopeless—choose to fight each other to the death. Juba won. On his order, a slave then slew him. Ibid.

- Theodor Mommsen, Römische Geschichte, band 5 (Leipzig 1885), translated as The Provinces of the Roman Empire (London 1886, reprint New York 1996), 310–311 [in Chap. XIII "The African Provinces"].

- "The Roman senate supervised, intrigued, and fomented internecine wars in order to weaken the Numidian kings and make them into docile clients." Abdallah Laroui, L'Histoire du Maghreb: Un essai de synthèse (Paris: Librairie François Maspero 1970), translated as The History of the Maghrib. An Interpretive Essay (Princeton University 1977), 54.

- Numidia had already been annexed by Julius Caesar (see above: Juba I).

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), quote on p. 45.

- Duane W. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene (New York: Routledge 2003), Libyka, 183–211, On Arabia, 227–243.

- Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (1971), 31.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), 43–46.

- Theodor Mommsen,Römische Geschichte, band 5 (Leipzig 1885), translated as The Provinces of the Roman Empire (London 1886, 1909; reprint Barnes & Noble 1996) at II: 307-311 (Caesar's African policy), 311–313 (Juba II).

- Tacitas, The Annals of Imperial Rome (Penguin 1956, rev. 1989), 168–170 (IV, 24–27).

- H. H. Scullard, From the Gracchi to Nero. A history of Rome from 133BC to AD68 (1959, 4th ed. 1976), 306.

- Brett and Fentress, The Berbers (1996), 47.

- On Tacfarinas: Marguerite Rachet, Rome et les Berberes (Bruxelles: Latomus Revue d'Etudes Latines 1970), 82–143.

- Cornelius Tacitus, Ab excessu divi Augusti (c.105–117), translated as The Annals of Imperial Rome (London: Penguin 1956, rev. 1989). Tacfarinas appears in five entries spread across Books II, III, IV, totaling close to six pages in the Penguin edition.

- See above, in this article.

- Sallust (86–c.35), Bellum Iugurthinum (c.44–40), translated as The Jugurthine War (Penguin 1963).

- E.g., Abdallah Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970; Princeton University 1977), 31, note 9.

- Tacitus, The Annals of Imperial Rome ([c.AD 117]; Penguin 1956, rev. 1989), 103 (II,50).

- A. Mahjoubi and P. Salama, "The Roman and post-Roman period in North Africa" 261–285: 270–272, in G. Mokhtar, editor, General History of Africa, vol. II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa (Paris: UNESCO 1990).

- See History of Roman era Tunisia, subsection Agricultural lands.

- Hédi Slim, Ammar Mahjoubi, Khaled Belkhoha, Abdelmajid Ennabli, L'Antiquité (Tunis: Sud Éditions 2010), 169–170 (e.g., Roman colonists, land registration), 192–195 (agriculture, from Punic variety to Roman monoculture). [Histoire Générale de la Tunisie, Tome 1].

- A. Mahjoubi and P. Salama, "The Roman and post-Roman period in North Africa" 261–285, 261, in G. Mokhtar, editor, General History of Africa, vol. II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa (Paris: UNESCO 1990).

"[T]he areas traditionally roamed by the nomads were steadily reduced and limited.... [A]ll the autochthonous nomads, and all the sedentary inhabitants who did not live in the few cities spared... were either reduced to abject poverty or driven into the steppes and the desert." Ibid.

- H. H. Scullard, From the Gracchi to Nero (London: Methuen 1959, 4th ed. 1976), 289. Scullard cites Ronald Symes, "Tacfarinas, the Musulamii and Thubursicu", 113–130, in Studies in Roman Economic and Social History (Princeton Univ. 1951).

- Cornelius Tacitus, Ab excessu divi Augusti (c.105–117), translated as The Annals of Imperial Rome (London: Penguin 1956, rev. 1989), 103 (II,50), 129–130 (III,19–21).

- A. Mahjoubi and P. Salama, "The Roman and post-Roman period in North Africa", 261-285: 261-262 (quote), 269-272, in G. Mokhtar, editor, General History of Africa, vol. II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa (Paris: UNESCO 1990).

- Abdallah Laroui, The History of the Maghrib (Paris 1970; Princeton University 1977), 33-34, 55; cf. 382.

- Tacitus, The Annals of Imperial Rome ([c.AD 117]; Penguin 1956, rev. 1989), 154-155 (III,72-74), 168-170 (IV,22-25).

- Hédi Slim, Ammar Mahjoubi, Khaled Belkhoha, Abdelmajid Ennabli, L'Antiquité (Tunis: Sud Éditions 2010), 165-167 (Tacfarinas). [Histoire Générale de la Tunisie, Tome 1].

- A. Mahjoubi and P. Salama, "The Roman and post-Roman period in North Africa" 261-285: 261-262, in G. Mokhtar, editor, General History of Africa, vol. II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa (Paris: UNESCO 1990).

- Cf. Hédi Slim, Ammar Mahjoubi, Khaled Belkhoha, Abdelmajid Ennabli, L'Antiquité (Tunis: Sud Éditions 2010), 167-169. [Histoire Générale de la Tunisie, Tome 1].