Bethel, Ohio

Bethel is a village in Clermont County, Ohio, United States.[6] The population was 2,711 at the 2010 census. Bethel was founded in 1798 by Obed Denham as Denham Town, in what was then the Northwest Territory. Bethel is the home of the first movie theater in Ohio which was founded in 1908 by Aaron Little.

Bethel, Ohio | |

|---|---|

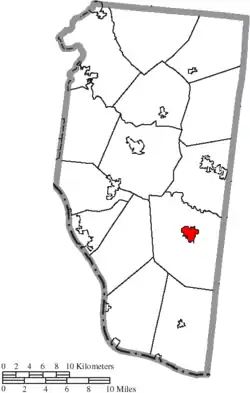

Location of Bethel, Ohio | |

Location of Bethel in Clermont County | |

| Coordinates: 38°57′47″N 84°4′54″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Clermont |

| Township | Tate |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.43 sq mi (3.71 km2) |

| • Land | 1.43 sq mi (3.70 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.01 km2) |

| Elevation | 883 ft (269 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 2,711 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 2,811 |

| • Density | 1,969.87/sq mi (760.40/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 45106 |

| Area code(s) | 513 |

| FIPS code | 39-06068[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1064426[2] |

| Website | bethel-oh |

Gallery

Bethel corporation limit sign.

Bethel corporation limit sign. Looking west on East Plane Street in Bethel.

Looking west on East Plane Street in Bethel. The Starlite Drive-In.

The Starlite Drive-In. The Starlite Drive-In.

The Starlite Drive-In.

History

Bethel was originally called Plainfield, and under the latter name was platted in 1798.[7] The town site was replatted in 1802 under the name Bethel.[7] The present name is after Bethel, a city in the Hebrew Bible.[8] A post office in Bethel has been in operation since 1815.[9] Bethel, along with other townships in the tri-state area near Cincinnati, has been a target for Ku Klux Klan membership and recruitment.[10]

"White Sunday" (June 14, 2020)

Bethel gained national attention in June 2020, when opposing advocacy groups clashed and Black Lives Matter demonstrators became the victims of acts of violence from the counter-protesters, some carrying guns.[11] The local protest, a part of the larger George Floyd protests, attracted counter-protesters from outside of Bethel, including several motorcycle gangs, Back-the-Blue groups, and Second Amendment advocates. On the day of the protest, 250 motorcycles arrived and occupied the area reserved for the demonstration.[12] In front of local police officers, one Black Lives Matter protester was assaulted. The protester has pressed charges as of Tuesday, June 16, 2020.[13] Counter-protesters were recorded screaming racial slurs at several of the Black Lives Matter demonstrators, including repeated use of the term "nigger". Black Lives Matter demonstrators also had their signs ripped from their hands and torn up by the counter-protesters while local police stood by watching.[14]

Geography

Bethel is located at 38°57′47″N 84°4′54″W (38.963171, -84.081787).[15]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 1.41 square miles (3.65 km2), of which 1.40 square miles (3.63 km2) is land and 0.01 square miles (0.03 km2) is water.[16]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 634 | — | |

| 1880 | 582 | −8.2% | |

| 1890 | 625 | 7.4% | |

| 1900 | 850 | 36.0% | |

| 1910 | 1,201 | 41.3% | |

| 1920 | 1,340 | 11.6% | |

| 1930 | 1,312 | −2.1% | |

| 1940 | 1,604 | 22.3% | |

| 1950 | 1,932 | 20.4% | |

| 1960 | 2,019 | 4.5% | |

| 1970 | 2,214 | 9.7% | |

| 1980 | 2,231 | 0.8% | |

| 1990 | 2,407 | 7.9% | |

| 2000 | 2,637 | 9.6% | |

| 2010 | 2,711 | 2.8% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 2,811 | [4] | 3.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[17] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 2,711 people, 1,052 households, and 681 families living in the village. The population density was 1,936.4 inhabitants per square mile (747.6/km2). There were 1,182 housing units at an average density of 844.3 per square mile (326.0/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 97.3% White, 0.4% African American, 0.1% Native American, 0.1% Asian, 0.4% Pacific Islander, 0.1% from other races, and 1.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.0% of the population.

There were 1,052 households, of which 39.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.3% were married couples living together, 18.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 35.3% were non-families. 30.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.56 and the average family size was 3.16.

The median age in the village was 33.8 years. 29% of residents were under the age of 18; 9.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.4% were from 25 to 44; 22.4% were from 45 to 64; and 12.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the village was 46.5% male and 53.5% female.

2000 census

As of the census[5] of 2000, there were 2,637 people, 1,012 households, and 682 families living in the village. The population density was 1,969.2 people per square mile (759.8/km2). There were 1,099 housing units at an average density of 820.7 per square mile (316.7/km2). The racial makeup of the village was 98.29% White, 0.11% African American, 0.19% Native American, 0.19% Asian, and 1.21% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.72% of the population.

There were 1,012 households, out of which 40.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.5% were married couples living together, 15.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.6% were non-families. 29.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.22.

In the village, the population was spread out, with 31.9% under the age of 18, 8.5% from 18 to 24, 30.9% from 25 to 44, 15.8% from 45 to 64, and 13.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females there were 87.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.9 males.

The median income for a household in the village was $31,385, and the median income for a family was $38,448. Males had a median income of $31,829 versus $23,844 for females. The per capita income for the village was $15,071. About 16.4% of families and 20.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 26.9% of those under age 18 and 20.1% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Bethel has a public library, a branch of the Clermont County Public Library.[18]

Notable people

- Libbie C. Riley Baer (1849–1929), poet

- Ulysses S. Grant - President of the United States and Commanding General of the United States Army

- Ulysses S. Grant Jr. - attorney and entrepreneur, a son of President Grant

- Thomas Morris - U.S. Senator from Ohio

- Steven M. Newman - the World Walker

- Dick Scott - Cincinnati Reds pitcher[19]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Description of the town of Bethel, Ohio".

- Everts, Louis H. (1880). History of Clermont County, Ohio, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. p. 324.

- Overman, William Daniel (1958). Ohio Town Names. Akron, OH: Atlantic Press. p. 13.

- "Clermont County". Jim Forte Postal History. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- "KKK Recruiting in Tri-State?". fox19.com. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- Glynn, Erin; Knight, Cameron (June 15, 2020). "Bethel police investigating 10 incidents after counter-protesters descended on BLM march". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- "Opposing advocacy groups clash in Bethel Sunday afternoon". WCPO-TV. June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Rex Chapman [@RexChapman] (June 15, 2020). "A BLM protestor was sucker punched directly in front of a police-officer — and not a damn thing was done by the officer to protect and serve the protestor.

Madness..." (Tweet) – via Twitter. - "What Happened In Bethel, Ohio?". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved 2020-07-05.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-07-02. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Locations". Clermont County Public Library. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Allen, Lee (2006). The Cincinnati Reds. Kent State University Press, p. 70. ISBN 978-0-87338-886-3.