Biotin deficiency

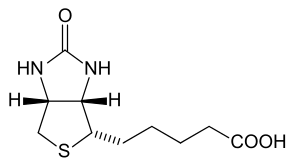

Biotin deficiency is a nutritional disorder which can become serious, even fatal, if allowed to progress untreated. It can occur in people of any age, ancestry, or gender. Biotin is part of the B vitamin family. Biotin deficiency rarely occurs among healthy people because the daily requirement of biotin is low, many foods provide adequate amounts of it, intestinal bacteria synthesize small amounts of it, and the body effectively scavenges and recycles it in the kidneys during production of urine. However, deficiencies can be caused by consuming raw egg whites over a period of weeks to months. Egg whites contain high levels of avidin, a protein that binds biotin strongly. When cooked, avidin is partially denatured and binding to biotin is reduced. However one study showed that 30-40% of the avidin activity was still present in the white after frying or boiling.[1] Genetic disorders such as biotinidase deficiency, multiple carboxylase deficiency, and holocarboxylase synthetase deficiency can also lead to inborn or late-onset forms of biotin deficiency. In all cases – dietary, genetic, or otherwise – supplementation with biotin is the primary method of treatment.

| Biotin deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

| Biotin | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Signs and symptoms

- Rashes including red, patchy ones near the mouth (erythematous periorofacial macular rash)

- Fine and brittle hair

Psychological

- Hallucinations[2]

- Lethargy[2]

- Mild depression, which may progress to profound fatigue and, eventually, to somnolence

- Generalized muscular pains (myalgias)

- Paresthesias

Causes

- Total parenteral nutrition without biotin supplementation: Several cases of biotin deficiency in patients receiving prolonged total parenteral nutrition (TPN) therapy without added biotin have been reported. Therefore, all patients receiving TPN must also receive biotin at the recommended daily dose, especially if TPN therapy is expected to last more than 1 week. All hospital pharmacies currently include biotin in TPN preparations.

- Protein deficiency: A shortage of proteins involved in biotin homeostasis can cause biotin deficiency. The main proteins involved in biotin homeostasis are HCS, BTD (biotinidase deficiency) and SMVT

- Anticonvulsant therapy: Prolonged use of certain drugs (especially highly common prescription anti-seizure medications such as phenytoin, primidone, and carbamazepine), may lead to biotin deficiency; however, valproic acid therapy is less likely to cause this condition.[3] Some anticonvulsants inhibit biotin transport across the intestinal mucosa. Evidence suggests that these anticonvulsants accelerate biotin catabolism, which means that it's necessary for people to take supplemental biotin, in addition to the usual minimum daily requirements, if they're treated with anticonvulsant medication(s) that have been linked to biotin deficiency.

- Severe malnourishment

- Prolonged oral antibiotic therapy: Prolonged use of oral antibiotics has been associated with biotin deficiency. Alterations in the intestinal flora caused by the prolonged administration of antibiotics are presumed to be the basis for biotin deficiency.

- Genetic mutation: Mikati et al. (2006) reported a case of partial biotinidase deficiency (plasma biotinidase level of 1.3 nm/min/mL) in a 7-month-old boy. The boy presented with perinatal distress followed by developmental delay, hypotonia, seizures, and infantile spasms without alopecia or dermatitis. The child's neurologic symptoms abated following biotin supplementation and antiepileptic drug therapy. DNA mutational analysis revealed that the child was homozygous for a novel E64K mutation and that his mother and father were heterozygous for the novel E64K mutation.

Potential causes

- Smoking: Recent studies suggest that smoking can lead to marginal biotin deficiency because it speeds up biotin catabolism (especially in women).

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Excessive consumption of antidiuretics or inadequate levels of antidiuretic hormone

- Intestinal malabsorption caused by short bowel syndrome

- Ketogenic diet

Biochemistry

Biotin is a coenzyme for five carboxylases in the human body (propionyl-CoA carboxylase, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase, pyruvate carboxylase, and 2 forms of acetyl-CoA carboxylase.) Therefore, biotin is essential for amino acid catabolism, gluconeogenesis, and fatty acid metabolism. Biotin is also necessary for gene stability because it is covalently attached to histones. Biotinylated histones play a role in repression of transposable elements and some genes. Normally, the amount of biotin in the body is regulated by dietary intake, biotin transporters (monocarboxylate transporter 1 and sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter), peptidyl hydrolase biotinidase (BTD), and the protein ligase holocarboxylase synthetase. When any of these regulatory factors are inhibited, biotin deficiency could occur.[4]

Diagnosis

The most reliable and commonly used methods for determining biotin status in the body are:

- excretion of 3-hydroxyisovaleric acid and biotin in urine

- activity of propionyl-CoA carboxylase in lymphocytes

Treatment

In the United States, biotin supplements are readily available without a prescription in amounts ranging from 300 to 10,000 micrograms (30 micrograms is identified as Adequate Intake).

Epidemiology

Since biotin is present in many foods at low concentrations, deficiency is rare except in locations where malnourishment is very common. Pregnancy, however, alters biotin catabolism and despite a regular biotin intake, half of the pregnant women in the U.S. are marginally biotin deficient.

See also

References

- Durance TD (1991). "Residual Avid in Activity in Cooked Egg White Assayed with Improved Sensitivity". Journal of Food Science. 56 (3): 707–709. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb05361.x.

- Thompson et al. 2003, p. 315.

- Krause et al. 1982, p. 485.

- Said, H (2011). "Biotin: biochemical, physiological and clinical aspects". Subcellular Biochemistry. 56: 1–19. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2199-9_1. ISBN 978-94-007-2198-2. PMID 22116691. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Possible references

- Adhisivam B, Mahto D, Mahadevan S (March 2007). "Biotin responsive limb weakness". Indian Pediatr. 44 (3): 228–30. PMID 17413203.

- Baykal T, Gokcay G, Gokdemir Y, Demir F, Seckin Y, Demirkol M, Jensen K, Wolf B (2005). "Asymptomatic adults and older siblings with biotinidase deficiency ascertained by family studies of index cases". J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 28 (6): 903–12. doi:10.1007/s10545-005-0161-3. PMID 16435182. S2CID 22277450.

- Boas MA (1927). "The Effect of Desiccation upon the Nutritive Properties of Egg-white". Biochem. J. 21 (3): 712–724.1. doi:10.1042/bj0210712. PMC 1251968. PMID 16743887.

- Dobrowolski SF, Angeletti J, Banas RA, Naylor EW (February 2003). "Real time PCR assays to detect common mutations in the biotinidase gene and application of mutational analysis to newborn screening for biotinidase deficiency". Mol. Genet. Metab. 78 (2): 100–7. doi:10.1016/S1096-7192(02)00231-7. PMID 12618081.

- Forbes GM, Forbes A (1997). "Micronutrient status in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition". Nutrition. 13 (11–12): 941–4. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00334-1. PMID 9433708.

- Genc GA, Sivri-Kalkanoğlu HS, Dursun A, Aydin HI, Tokatli A, Sennaroglu L, Belgin E, Wolf B, Coşkun T (February 2007). "Audiologic findings in children with biotinidase deficiency in Turkey". Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 71 (2): 333–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.11.001. PMID 17161472.

- González EC, Marrero N, Frómeta A, Herrera D, Castells E, Pérez PL (July 2006). "Qualitative colorimetric ultramicroassay for the detection of biotinidase deficiency in newborns". Clin. Chim. Acta. 369 (1): 35–9. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2006.01.009. PMID 16480705.

- Hassan YI, Zempleni J (July 2006). "Epigenetic regulation of chromatin structure and gene function by biotin". J. Nutr. 136 (7): 1763–5. doi:10.1093/jn/136.7.1763. PMC 1479604. PMID 16772434.

- Higuchi R, Mizukoshi M, Koyama H, Kitano N, Koike M (February 1998). "Intractable diaper dermatitis as an early sign of biotin deficiency". Acta Paediatr. 87 (2): 228–9. doi:10.1080/08035259850157732. PMID 9512215.

- László A, Schuler EA, Sallay E, Endreffy E, Somogyi C, Várkonyi A, Havass Z, Jansen KP, Wolf B (2003). "Neonatal screening for biotinidase deficiency in Hungary: clinical, biochemical and molecular studies". J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 26 (7): 693–8. doi:10.1023/B:BOLI.0000005622.89660.59. PMID 14707518. S2CID 12601233.

- Mock DM (February 1999). "Biotin status: which are valid indicators and how do we know?". J. Nutr. 129 (2S Suppl): 498S–503S. doi:10.1093/jn/129.2.498S. PMID 10064317.

- Mock DM (December 1991). "Skin manifestations of biotin deficiency". Semin Dermatol. 10 (4): 296–302. PMID 1764357.

- Möslinger D, Mühl A, Suormala T, Baumgartner R, Stöckler-Ipsiroglu S (December 2003). "Molecular characterisation and neuropsychological outcome of 21 patients with profound biotinidase deficiency detected by newborn screening and family studies". Eur. J. Pediatr. 162 (Suppl 1): S46–9. doi:10.1007/s00431-003-1351-3. PMID 14628140. S2CID 6490712.

- Neto EC, Schulte J, Rubim R, Lewis E, DeMari J, Castilhos C, Brites A, Giugliani R, Jensen KP, Wolf B (March 2004). "Newborn screening for biotinidase deficiency in Brazil: biochemical and molecular characterizations". Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 37 (3): 295–9. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2004000300001. PMID 15060693.

- Schulpis KH, Gavrili S, Tjamouranis J, Karikas GA, Kapiki A, Costalos C (May 2003). "The effect of neonatal jaundice on biotinidase activity". Early Hum. Dev. 72 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1016/S0378-3782(02)00097-X. PMID 12706308.

- Thompson, J, Manore M, Sheeshka J (2010). "Nutrients involved in energy metabolism and blood health". In Bennett G, Swieg C, et al. (eds.). Nutrition: A functional Approach. Toronto: Pearson Canada. p. 353. ISBN 9780321740212.

- Velázquez A (1997). "Biotin deficiency in protein-energy malnutrition: implications for nutritional homeostasis and individuality". Nutrition. 13 (11–12): 991–2. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00345-6. PMID 9433719.

- Weber P, Scholl S, Baumgartner ER (July 2004). "Outcome in patients with profound biotinidase deficiency: relevance of newborn screening". Dev Med Child Neurol. 46 (7): 481–4. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2004.tb00509.x. PMID 15230462.

- Welling DB (August 2007). "Long-term follow-up of hearing loss in biotinidase deficiency". J. Child Neurol. 22 (8): 1055. doi:10.1177/0883073807305789. PMID 17761663. S2CID 39911504.

- Wiznitzer M, Bangert BA (July 2003). "Biotinidase deficiency: clinical and MRI findings consistent with myelopathy". Pediatr. Neurol. 29 (1): 56–8. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(03)00042-0. PMID 13679123.

- Wolf B (2001). "Disorders of biotin metabolism". In Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, et al. (eds.). The metabolic & molecular bases of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 3935–62. ISBN 978-0-07-913035-8.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |