Blandford, Massachusetts

Blandford is a town in Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 1,233 at the 2010 census.[1] It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. It was the home of the Blandford Ski Area.

Blandford, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

The First Congregational Church of Blandford, known locally as "The White Church" | |

Seal | |

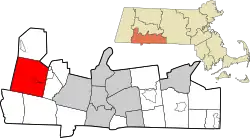

Location in Hampden County in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°10′50″N 72°55′40″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Hampden |

| Settled | 1735 |

| Incorporated | April 10, 1741 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| Area | |

| • Total | 53.4 sq mi (138.4 km2) |

| • Land | 51.6 sq mi (133.6 km2) |

| • Water | 1.9 sq mi (4.8 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,452 ft (443 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,233 |

| • Density | 24/sq mi (9.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 01008 |

| Area code(s) | 413 |

| FIPS code | 25-06085 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0619383 |

| Website | townofblandford |

History

Blandford was first settled in 1735 primarily by Scots-Irish settlers and was officially incorporated on November 10, 1741. Because of these Scots-Irish families, Blandford was originally called "New Glasgow" after Glasgow, Scotland, but was renamed "Blandford" at the time of incorporation. While the petition of incorporation from the settlers asked that the town be named "Glascow" (as misspelled in source document), William Shirley, the newly appointed governor of the province of Massachusetts, ignored their request and named the town "Blandford" after the ship that brought him from England.[2]

The name change came at a cost to the townspeople. The people of Glasgow, Scotland, had promised the settlers a gift of a church bell if they named the town after their city. With the town now named Blandford, the bell was never sent.[2] Today, Glasgow Road near the center of Blandford is a silent reminder of these events.

Settlement came to Blandford and other "hilltowns" some 75 years after the more fertile alluvial lowlands along the Connecticut River were cultivated with tobacco and other commodity crops. In contrast, farming in the hilltowns was of a hardscrabble subsistence nature due to thin, rocky soil following Pleistocene glaciation and a slightly cooler climate, although upland fields were sometimes less subject to unseasonal frosts. Initial settlement in the nearby Pioneer Valley was by English Puritans, whereas Blandford's Scots-Irish settlers were Presbyterian, and their English was still somewhat influenced by Gaelic. Thus there were significant ethnic, religious, economic, and linguistic differences between these adjacent regions of settlement.

Hugh Black was the first settler to arrive in the fall of 1735. James Baird came shortly thereafter. After these two arrived, several other families soon followed, including Reed, McClintock, Taggart, Brown, Anderson, Hamilton, Wells, Blair, Stewart, Montgomery, Boies, Ferguson, Campbell, Wilson, Sennett, Young, Knox and Gibbs. Most of these families first settled in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, in 1727 before coming to Blandford.[2]

But not all of these families were Scots-Irish. For example, the Boies was a family of French origin, originally named Du Bois, who were prominent during the reign of Louis XIV. They were driven from France during the Huguenot persecutions to the northern part of Ireland. In Ireland the spelling of their name changed from Du Bois to the Boies before descendants of the family eventually migrated to the United States and settled in Blandford.[2]

The first meeting house (used both as a church and for town government meetings) was erected in 1740, paid for by certain men—Jacob Lawton, Francis Wells, John Faye, and Francis Brindley (referred to as the proprietors)—who owned the land sold to the settlers. The agreement to build it stipulated that it should have glass windows, though those were not supplied until 12 years later. For 13 years the building had no floor except for a few loose boards, the earth and rocks. The seats were blocks, boards and common benches. The pulpit was nothing but a square box. In 1759 it was voted "to make a pulpit for the minister and to build seats". In 1786 the house was first plastered. It was not until 1805, 65 years after it was commenced, that the meeting house was completed.[2]

In keeping with its Scottish heritage, the church was originally Presbyterian, unlike the Congregational churches that were in most new settlements. Its first pastor was William McClenathan, 1744 to 1747. But the roots of the church were said to have dated back to 1735, when in Hopkinton the settlers then preparing to move to Blandford created "the religious organization which flourished contemporaneously with the early settlement in the wilderness."[2]

King George's War (1744–1748; third of the four French & Indian Wars) led to conflict between the settlers and local Native Americans. In 1744 four garrisons were built due to growing tension and fears of the settlers. In 1746, Rev. William McClenathan went to Hartford and Adam Knox went to Northampton to procure soldiers. The tense situation extended into 1749. In spring, the settlers, except for four families, fled to neighboring towns. Upon returning in the fall the townspeople built three new forts. These forts were used through 1750 as a place for common shelter at night, and settlers went armed to their work and church. Fortunately no serious confrontations appear to have occurred between the settlers and the Natives in this period.[2]

The settlers were so poor that they frequently asked for assistance from the men that had sold them their land, and often petitioned the General Court for money grants and remission of taxes. Among the various forms of relief provided, the court once gave 40 bushels of salt to the town.[2]

But the townspeople also found relief in other ways. In 1757, due to a conflict between Rev. Morton and the town, a church council meeting was held. The town agreed to pay the tavern owned by Mr. Root where the meeting was held for "Each Meal of Vittles", lodging and "the strong Drink that the Council drink while they are Hear on our Business."[2]

"Strong drink" was apparently not confined to just church council meetings. At town-meetings those attending frequently took a recess of an hour for the purpose of refreshing themselves at the tavern. Tradition says that in those times the man who could drink the most and walk the straightest was a hero. And family gatherings were noted as typically having a liberal standing supply. Along with other parts of the country, by 1840 drinking alcoholic beverages had fallen out of favor and total abstinence took hold "more or less" in Blandford.[2]

While alcohol may have been common, attitudes toward religion were very traditional. The leaders of the Presbyterian church music were chosen at town meetings and were encouraged to conduct it in "the good old way". In 1771 the question was raised whether the singing should be carried on with the beat and was rejected. Caleb Taylor, of Westfield, was the first singing-master, and when he named the tune and sang with the beat, many were so shocked at what they termed the "indecency of the method" that they left the church.[2]

Eventually the community decided to leave behind the suggestive beat of Presbyterian music and converted in 1800 to the more conservative Congregational Church. The reason: "from the inconvenience attending to its first form".[2]

Blandford was actively involved in the American Revolutionary War, providing both men and material throughout to the American cause. When the first alarm came from Lexington, Massachusetts, in 1775, site of the Battle of Lexington, 36 men from Blandford and the neighboring town of Chester set out, under the command of Captain John Ferguson of Blandford, to assist their fellow patriots.[2]

During the Revolutionary War, General Henry Knox led a detachment of troops that hauled cannon from Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain over the Berkshires and through Blandford, eventually on to Boston to bluff the British into withdrawing from the city. His route is now called the Henry Knox Trail.

Blandford was opposed to the War of 1812, and sent Jedediah Smith as a delegate to the Northampton Convention. Approximately 65 men from Blandford served in several regiments in the Civil War, notably the 1st Cavalry and various Massachusetts regiments such as the 27th, 31st, 37th, 46th, among others.[2]

Population density in Blandford and other hilltowns was limited by outmigration by about 1800 as more productive land in western New York and the Northwest Territory became available. However, emigrants were typically young men and women, while the older generation and usually one or two children usually remained in place and farms were not yet abandoned. Then the Industrial Revolution drew additional workers away from hilltown farms, especially after 1850 when steam engines fueled by local wood or by coal began to replace water power. Hilltown farms began to be abandoned about this time and slowly reverted to forest, leaving stone walls and cellar holes behind as farm buildings rotted away. In other cases farming became a part-time way of life and industrial wages enabled buying manufactured goods, whereas previously virtually everything used on subsistence farms was homemade or bartered for.

As a result of these factors, by 1880 the population of Blandford had fallen to 979 from 1,418 only 30 years earlier. But even in 1879 Blandford remained an active, if declining, community.

Blandford Center, the site of the early settlements, in 1879 had a population of about 300 with two churches, one hotel, two stores, a post office, a school, fairgrounds and two cemeteries, with a focus on agriculture. Due to poor soils, production of grain was limited and hay the primary crop. Instead of raising crops, farmers purchased large quantities of grain for stock raising and manufactured butter and cheese. Agriculture was noted as having limited profitability.[2]

Three miles away stood North Blandford, once a substantial manufacturing location due to its excellent water power provided by numerous mountain streams. In the 1850s there were several woolen mills, paper mills, tanneries and other manufacturers. By 1879 that had declined which lead to the Waite & Son cattle-card factory, Diamond Cheese Factory, and two small tanneries. In addition, North Blandford had a church, school, two stores, post office and a population of about 300 as well.[2]

Cheese and butter making were important businesses in Blandford throughout the 19th century. Their introduction was attributed to Amos Collins, a Connecticut merchant, who had settled in Blandford in 1807. He was so successful that by the time he left Blandford in 1816, Collins had gained a comfortable fortune.[2]

By 1879 the town was known to be rich in minerals such as carbonate of lime, chromate of iron, steatite, crystallized actinolite, mamillary chalcedony, kyanite, rose quartz, mica, sulphuret of iron and others. One story was that John Baird discovered lead and silver ore near the north line of town around 1795. Due to a "superstitious belief" he did not pursue his discoveries, did not reveal their location, and the secret died with him. After his death many fruitless efforts were undertaken to try to locate it.[2]

Blandford sits along an important travel corridor. The Eighth Massachusetts Turnpike Association, laid out in 1800, passed through Blandford onto Chester, as did the Eleventh Turnpike Association running from the south line of the state to Becket via the Pittsfield Road.[2] Today the Massachusetts Turnpike, Interstate 90, bisects the town, although there is no exit.

Not just turnpikes passed through Blandford, so did trolleys – though briefly. In 1912 electrified street railways (trolley car lines) covered Massachusetts, connecting towns and densely blanketing urban areas like Boston as in virtually all major American cities. They offered inexpensive, frequent and fast transportation, with some lines that connected urban areas (interurbans) regularly exceeding 50 mph (80 km/h). Thousands and thousands of miles of these lines were built at huge expense over a few decades across the United States but would soon be made obsolete by inexpensive autos, namely the Ford Model T. By the late 1940s few of these lines remained. Tiny remnants of this once huge network still exist as the street-level portions of the T, Boston's subway system.[3]

The last significant line built in Massachusetts, by the Berkshire Street Railway, was from East Lee to Huntington via Blandford, opening August 15, 1917. The Berkshire suspended service on this 24-mile (39 km) route in October 1918 for the winter months. It was never reopened when a request for operating subsidies from local communities was rejected. Today, the right of way for this line, including the ties for the rails, the bases of the wooden poles that carried the overhead electric lines, viaducts for carrying the trolleys over streams and gullies, and foundations for its buildings, can still be found in the forest—most easily around North Blandford.[3]

Geography

The town is located near the eastern edge of the Berkshire Hills, above an ancient rift zone where the Connecticut River Valley is downfaulted about 1,000 feet (300 m). The town's elevations range from about 400 feet (120 m) above sea level along streams approaching the Westfield River (a major tributary of the Connecticut) to hilltops as high as 1,700 feet (520 m). Elevations increase to the west with expansive views eastward across the Connecticut River Valley as far as Mount Monadnock in southern New Hampshire. Local relief is as high as 500 feet (150 m) near streams flowing into the Westfield River, but away from these streams the town is characterised by rolling uplands.

Abandoned fields and pastures have reverted to forests of beech, birch, maple, hemlock, pine and oak. Land reserved for woodlots and never cleared was repeatedly logged; however, logging has fallen off in recent decades so forests are reclaiming some old growth qualities and animal species that have been absent or rare for some 200 years are returning.

Blandford has significant water resources in its streams and ponds. The city of Springfield has reserved the upper watershed of the Little River, a tributary of the Westfield, as the city's main water supply, Cobble Mountain Reservoir.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the town of Blandford has a total area of 53.4 square miles (138.4 km2), of which 51.6 square miles (133.6 km2) are land and 1.9 square miles (4.8 km2), or 3.48%, are water.[1] All of the town except for its southwest corner is part of the Westfield River watershed, although the river itself passes north and east of the town. The southwest corner of Blandford drains via Otis Reservoir to the Farmington River, which like the Westfield is a tributary of the Connecticut River.

The Blandford town center is in the east-central part of the town, along Massachusetts Route 23. Via MA 23 and U.S. Route 20, Blandford is 21 miles (34 km) west of Springfield, the largest city in western Massachusetts. Pittsfield is 27 miles (43 km) to the northwest via local roads.

Points of interest

Porter Memorial Library (Massachusetts)

The Porter Memorial Library is a public library,[4] established in 1891.[5] In fiscal year 2008, the town of Blandford spent 1.46% ($35,908) of its budget on its public library—some $28 per person.[6]

Other points of interest

- Blandford is home to the Blandford Ski Area, a small ski mountain opened by the Springfield Ski Club and since 2017 owned by Ski Butternut Ski Resort. 2015–16 marks its 80th year of operation. In 2017–2018 season it was not open due to renovations.

- The Blandford Fairgrounds plays host to the annual Labor Day weekend Blandford Fair. Home to old fashioned agricultural exhibits and competitions, a fun filled midway, and many musical acts each year. This fair is made possible by the hard work of many volunteers each year.[7]

- South of the fairgrounds is an historic white church building, that has just recently began to host services.

- The oldest cemetery adjacent to Route 23 includes gravesites for original settlers, some born in Ireland.

- The Blandford Club, a private nine-hole golf course with tennis facilities, was established in 1909 and recently celebrated 100 years of operation. It is located at 17 North Street, right past the historic White Church of Blandford.[8]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,418 | — |

| 1860 | 1,256 | −11.4% |

| 1870 | 1,026 | −18.3% |

| 1880 | 979 | −4.6% |

| 1890 | 871 | −11.0% |

| 1900 | 836 | −4.0% |

| 1910 | 717 | −14.2% |

| 1920 | 479 | −33.2% |

| 1930 | 545 | +13.8% |

| 1940 | 479 | −12.1% |

| 1950 | 597 | +24.6% |

| 1960 | 636 | +6.5% |

| 1970 | 863 | +35.7% |

| 1980 | 1,038 | +20.3% |

| 1990 | 1,187 | +14.4% |

| 2000 | 1,214 | +2.3% |

| 2010 | 1,233 | +1.6% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States Census records and Population Estimates Program data.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18] | ||

As of the census[19] of 2000, there were 1,214 people, 456 households, and 350 families residing in the town. The population density was 23.5 people per square mile (9.1/km2). There were 526 housing units at an average density of 10.2 per square mile (3.9/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 98.76% White, 0.49% African American, 0.16% Native American, 0.25% Asian, and 0.33% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.33% of the population.

There were 456 households, out of which 33.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 65.4% were married couples living together, 6.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 23.2% were non-families. Of all households 19.5% were made up of individuals, and 6.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.03.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 24.1% under the age of 18, 6.6% from 18 to 24, 27.8% from 25 to 44, 31.8% from 45 to 64, and 9.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.1 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $52,935, and the median income for a family was $59,375. Males had a median income of $37,708 versus $32,917 for females. The per capita income for the town was $24,285. About 1.7% of families and 3.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.0% of those under age 18 and 5.9% of those age 65 or over.

Notable people

- George Ashmun, born in Blandford, United States congressman from Massachusetts[20]

- Winifred E. Lefferts (also known as Winifred Lefferts Arms), painter, designer and philanthropist

- Charles A. Taggart, awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Civil War

See also

References

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Blandford town, Hampden County, Massachusetts". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- History of the Connecticut Valley (1879) pp. 1074-1081

- From Boston to the Berkshires – Pictorial Review of Electric Transportation in Massachusetts. Boston Street Railway Association (1990)

- http://mblc.state.ma.us/libraries/directory/index.php Retrieved 05-18-2010

- Report of the Free Public Library Commission of Massachusetts. v.9 (1899)

- July 1, 2007, through June 30, 2008; cf. The FY2008 Municipal Pie: What's Your Share? Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Board of Library Commissioners. Boston: 2009. Available: Municipal Pie Reports Archived January 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blandford, Massachusetts. |

- Town of Blandford official website

- MHC Reconnaissance Town Survey Report: Blandford Massachusetts Historical Commission, 1982.