Boötes void

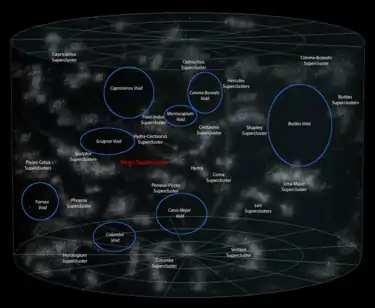

The Boötes void (or the Great Nothing)[1] is an enormous, approximately spherical region of space, containing very few galaxies. It is located in the vicinity of the constellation Boötes, hence its name. Its center is located at approximately right ascension14h 50m and declination 46°.[2]

Description

At nearly 330 million light-years in diameter[3] (approximately 0.27% of the diameter of the observable Universe), or nearly 236,000 Mpc3 in volume, the Boötes void is one of the largest-known voids in the Universe, and is referred to as a supervoid. Its discovery was reported by Robert Kirshner et al. (1981) as part of a survey of galactic redshifts. The center of the Boötes void is approximately 700 million light-years from Earth.[4]

Other astronomers soon discovered that the void contained a few galaxies. In 1987, J. Moody, Robert P. Kirshner, G. MacAlpine, and S. Gregory published their findings of eight galaxies in the void.[5] M. Strauss and John Huchra announced the discovery of a further three galaxies in 1988, and Greg Aldering, G. Bothun, Robert P. Kirshner, and Ron Marzke announced the discovery of fifteen galaxies in 1989. By 1997, the Boötes void was known to contain 60 galaxies.

According to astronomer Greg Aldering, the scale of the void is such that "If the Milky Way had been in the center of the Boötes void, we wouldn't have known there were other galaxies until the 1960s."[6]

The Hercules Supercluster forms part of the near edge of the void.[2]

Using a rough estimate of about 1 galaxy every 10 million light-years (about 4 times further than the Andromeda Galaxy is from Earth), there should be approximately 2,000 galaxies in the Boötes void.[7]

Origins

There are no major apparent inconsistencies between the existence of the Boötes void and the Lambda-CDM model of cosmological evolution.[8] It has been theorized that the Boötes void was formed from the merger of smaller voids, much like the way in which soap bubbles coalesce to form larger bubbles. This would account for the small number of galaxies that populate a roughly tube-shaped region running through the middle of the void.[6]

Confusion with Barnard 68

Boötes void has been often associated with images of Barnard 68, a dark nebula that does not allow light to pass through; however, the images of Barnard 68 are much darker than those observed of Boötes void, as the nebula is much closer and there are fewer stars in front of it, as well as its being a physical mass that blocks light passing through.

See also

Footnotes

- Cowen, Ron (2000). "Big, Bigger... Biggest?". Science News. 158 (7): 104–105. doi:10.2307/3981218. JSTOR 3981218.

- Kirshner, Robert P.; Oemler, Augustus, Jr.; Schechter, Paul L.; Shectman, Stephen A. (Mar 1, 1987). "A survey of the Bootes void". Astrophysical Journal, Part 1. 314: 493–506. Bibcode:1987ApJ...314..493K. doi:10.1086/165080. ISSN 0004-637X.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "A Spongy Universe" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- "The Bootes Void". Archived from the original on 2011-08-07. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- Moody, J. Ward; Kirshner, Robert P.; MacAlpine, Gordon M.; Gregory, Stephen A. (March 1987). "Emission-line galaxies in the Bootes void". The Astrophysical Journal. 314: L33. Bibcode:1987ApJ...314L..33M. doi:10.1086/184846.

- "Filling the void - understanding the formation of the Bootes void in intergalactic space - Brief Article". Discover magazine. August 1995. Archived from the original on 2007-11-19. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- McCracken, Jason (July 30, 2013). "Next Stop: Voids". Blueship. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- "Cosmic_Voids" Retrieved on June 10, 2013

References

- Kirshner, R. P.; Oemler, A. J.; Schechter, P. L.; Shectman, S. A. (1981). "A million cubic megaparsec void in Bootes". The Astrophysical Journal. 248: L57–60. Bibcode:1981ApJ...248L..57K. doi:10.1086/183623.

- Kirshner, R. P.; Oemler, A. J.; Schechter, P. L.; Shectman, S. A. (1987). "A survey of the Bootes void". The Astrophysical Journal. 314: 493. Bibcode:1987ApJ...314..493K. doi:10.1086/165080.