Brittonic languages

The Brittonic, Brythonic or British Celtic languages (Welsh: ieithoedd Brythonaidd/Prydeinig; Cornish: yethow brythonek/predennek; Breton: yezhoù predenek) form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family; the other is Goidelic.[1] The name Brythonic was derived by Welsh Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython, meaning Ancient Britons as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon or Gael.

| Brittonic | |

|---|---|

| Brythonic, British Celtic | |

| Geographic distribution | Wales, Cornwall, Cumbria plus other areas in the west of England, Strathclyde, Brittany, Galicia |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Proto-language | Common Brittonic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | bryt1239 |

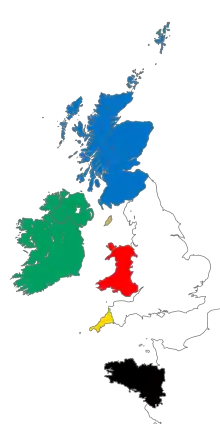

The Brittonic-speaking community around the sixth century. | |

The Brittonic languages derive from the Common Brittonic language, spoken throughout Great Britain south of the Firth of Forth during the Iron Age and Roman period. Also, North of the Forth, the Pictish language is considered to be related; it could be a Brittonic language, but it may have been a sister language. In the 5th and 6th centuries emigrating Britons also took Brittonic speech to the continent, most significantly in Brittany and Britonia. During the next few centuries the language began to split into several dialects, eventually evolving into Welsh, Cornish, Breton and Cumbric. Welsh and Breton continue to be spoken as native languages, while a revival in Cornish has led to an increase in speakers of that language. Cumbric is extinct, having been replaced by Goidelic and English speech. The Isle of Man and Orkney may also have originally spoken a Brittonic language, but this was later supplanted by Goidelic on the Isle of Man and Norse on Orkney. Due to emigration, there was a Brittonic community in the Kingdom of the Suebi in Galicia. There is also a community of Brittonic language speakers in Y Wladfa (the Welsh settlement in Patagonia).

Name

The names "Brittonic" and "Brythonic" are scholarly conventions referring to the Celtic languages of Britain and to the ancestral language they originated from, designated Common Brittonic, in contrast to the Goidelic languages originating in Ireland. Both were created in the 19th century to avoid the ambiguity of earlier terms such as "British" and "Cymric".[2] "Brythonic" was coined in 1879 by the Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython.[2][3] "Brittonic", derived from "Briton" and also earlier spelled "Britonic" and "Britonnic", emerged later in the 19th century.[4] It became more prominent through the 20th century, and was used in Kenneth H. Jackson's highly influential 1953 work on the topic, Language and History in Early Britain. Jackson noted that by that time "Brythonic" had become a dated term, and that "of late there has been an increasing tendency to use Brittonic instead."[3] Today, "Brittonic" often replaces "Brythonic" in the literature.[4] Rudolf Thurneysen used "Britannic" in his influential A Grammar of Old Irish, though this never became popular among subsequent scholars.[5]

Comparable historical terms include the Medieval Latin lingua Britannica and sermo Britannicus[6] and the Welsh Brythoneg.[2] Some writers use "British" for the language and its descendants, though due to the risk of confusion, others avoid it or use it only in a restricted sense. Jackson, and later John T. Koch, use "British" only for the early phase of the Common Brittonic language.[5]

Before Jackson's work, "Brittonic" (and "Brythonic") were often used for all the P-Celtic languages, including not just the varieties in Britain but those Continental Celtic languages that similarly experienced the evolution of the Proto-Celtic language element /kʷ/ to /p/. However, subsequent writers have tended to follow Jackson's scheme, rendering this use obsolete.[5]

The name "Britain" itself comes from Latin: Britannia~Brittania, via Old French Bretaigne and Middle English Breteyne, possibly influenced by Old English Bryten(lond), probably also from Latin Brittania, ultimately an adaptation of the native word for the island, *Pritanī.[7][8]

An early written reference to the British Isles may derive from the works of the Greek explorer Pytheas of Massalia; later Greek writers such as Diodorus of Sicily and Strabo who quote Pytheas' use of variants such as Πρεττανική (Prettanikē), "The Britannic [land, island]", and nēsoi brettaniai, "Britannic islands", with *Pretani being a Celtic word that might mean "the painted ones" or "the tattooed folk", referring to body decoration (see below).[9]

Evidence

Knowledge of the Brittonic languages comes from a variety of sources. The early language's information is obtained from coins, inscriptions, and comments by classical writers as well as place names and personal names recorded by them. For later languages, there is information from medieval writers and modern native speakers, together with place names. The names recorded in the Roman period are given in Rivet and Smith.[10]

Characteristics

The Brittonic branch is also referred to as P-Celtic because linguistic reconstruction of the Brittonic reflex of the Proto-Indo-European phoneme *kʷ is p as opposed to Goidelic c. Such nomenclature usually implies acceptance of the P-Celtic and Q-Celtic hypothesis rather than the Insular Celtic hypothesis because the term includes certain Continental Celtic languages as well. (For a discussion, see Celtic languages.)

Other major characteristics include:

- The retention of the Proto-Celtic sequences am and an, which mostly result from the Proto-Indo-European syllabic nasals.

- Celtic /w/ (written u in Latin texts and ou in Greek) became gw- in initial position, -w- internally, whereas in Gaelic it is f- in initial position and disappears internally:

- Proto-Celtic *windos "white, fair" became Welsh gwyn (masculine), gwen (feminine), Cornish gwynn, Breton gwenn. Contrast Irish fionn "fair".

- Proto-Celtic *wassos "servant, young man" became Welsh, Cornish and Breton gwas. Contrast Middle Irish foss.

Initial s-:

- Initial s- followed by a vowel was changed to h-:

- Welsh hen "old", hir "long", hafal "similar"

- Breton hen "ancient", hir "long", hañval "similar"

- Cornish hen "ancient", hir "long", haval "similar"

- Contrast Irish sean "old", síor "long", samhail "similarity"

- Initial s- was lost before /l/, /m/ and /n/:

- *slemon became Welsh llyfn, Cornish leven and Breton levn "smooth". Contrast Irish sleamhain "smooth, slimy"

- *smeru became Welsh mêr, Cornish mer, and Breton mel "marrow". Contrast Irish sméar

- The initial clusters sp-, sr-, sw- became f-, fr-, chw-:

- *sɸera became Welsh ffêr "ankle", Cornish fer "shank, lower leg" and Breton fer "ankle". Contrast Old Irish seir "heel, ankle"

- *srogna "nostril" became Welsh ffroen, Cornish frig and Breton froen. Contrast Irish srón

- *swīs "you" (plural) became Welsh chwi, Cornish hwy and Breton c'hwi. Contrast Old Irish síi

Lenition:

- Voiceless stops become voiced stops in intervocalic position:

- Voiced plosives /d/, /ɡ/ (later /j/, then lost), /b/, and /m/ became soft spirants in an intervocalic position and before liquids:

- Welsh dd [ð], th [θ], f [v]

- Cornish dh [ð], th [θ], v [v]

- Breton z, zh [z] or [h], v

Voiceless spirants:

- Geminated voiceless plosives transformed into spirants; /pː/ (pp), /kː/ (cc), /tː/ (tt) became /ɸ/ (later /f/), /x/ (ch/c'h), /θ/ (th/zh) before a vowel or liquid:

- *cippus > Breton kef, Cornish kyf, Welsh cyff, "tree trunk"

- *cattos > Breton kazh, Cornish kath, Welsh cath, "cat" vs. Irish cat

- *bucca > Breton boc'h, Cornish bogh, Welsh boch, "cheek"

- Voiceless stops become spirants after liquids:

- *artos "bear" > Welsh/Cornish arth, Breton arzh, compare Old Irish art

Nasal assimilation:

- Voiced stops were assimilated to a preceding nasal:

- Brittonic retains original nasals before -t and -k, whereas Goidelic alters -nt to -d, and -nk to -g:

- Breton kant "hundred" vs. Irish céad, Breton Ankou (personification of) Death, Irish éag 'die'

Classification

The family tree of the Brittonic languages is as follows:

- Common Brittonic ancestral to:

- Western Brittonic languages ancestral to:

- Southwestern Brittonic languages ancestral to:

| Common Brittonic | |||

| Western Brittonic | Southwestern Brittonic | ||

| Cumbric | Welsh | Cornish | Breton |

Brittonic languages in use today are Welsh, Cornish and Breton. Welsh and Breton have been spoken continuously since they formed. For all practical purposes Cornish died out during the 18th or 19th centuries, but a revival movement has more recently created small numbers of new speakers. Also notable are the extinct language Cumbric, and possibly the extinct Pictish. One view, advanced in the 1950s and based on apparently unintelligible ogham inscriptions, was that the Picts may have also used a non-Indo-European language.[12] This view, while attracting broad popular appeal, has virtually no following in contemporary linguistic scholarship.[13]

History and origins

The modern Brittonic languages are generally considered to all derive from a common ancestral language termed Brittonic, British, Common Brittonic, Old Brittonic or Proto-Brittonic, which is thought to have developed from Proto-Celtic or early Insular Celtic by the 6th century BC.[14]

Brittonic languages were probably spoken before the Roman invasion at least in the majority of Great Britain south of the rivers Forth and Clyde, though the Isle of Man later had a Goidelic language, Manx. Northern Scotland mainly spoke Pritennic, which became the Pictish language, which may have been a Brittonic language like that of its neighbours. The theory has been advanced (notably by T. F. O'Rahilly) that part of Ireland spoke a Brittonic language, usually termed Ivernic, before it was displaced by Primitive Irish, although the authors Dillon and Chadwick reject this theory as being implausible.

During the period of the Roman occupation of what is now England and Wales (AD 43 to c. 410), Common Brittonic borrowed a large stock of Latin words, both for concepts unfamiliar in the pre-urban society of Celtic Britain such as urbanization and new tactics of warfare as well as for rather more mundane words which displaced native terms (most notably, the word for "fish" in all the Brittonic languages derives from the Latin piscis rather than the native *ēskos - which may survive, however, in the Welsh name of the River Usk, Wysg). Approximately 800 of these Latin loan-words have survived in the three modern Brittonic languages.

It is probable that at the start of the Post-Roman period Common Brittonic was differentiated into at least two major dialect groups – Southwestern and Western (also we may posit additional dialects, such as Eastern Brittonic, spoken in what is now the East of England, which have left little or no evidence). Between the end of the Roman occupation and the mid 6th century the two dialects began to diverge into recognizably separate varieties, the Western into Cumbric and Welsh and the Southwestern into Cornish and its closely related sister language Breton, which was carried to continental Armorica. Jackson showed that a few of the dialect distinctions between West and Southwest Brittonic go back a long way. New divergencies began around AD 500 but other changes that were shared occurred in the 6th century. Other common changes occurred in the 7th century onward and are possibly due to inherent tendencies. Thus the concept of a Common Brittonic language ends by AD 600. Substantial numbers of Britons certainly remained in the expanding area controlled by Anglo-Saxons, but over the fifth and sixth centuries they mostly adopted the English language.[15][16][17]

The Brittonic languages spoken in what is now Scotland, the Isle of Man and what is now England began to be displaced in the 5th century through the settlement of Irish-speaking Gaels and Germanic peoples. The displacement of the languages of Brittonic descent was probably complete in all of Britain except Cornwall and Wales and the English counties bordering these areas such as Devon by the 11th century. Western Herefordshire continued to speak Welsh until the late nineteenth century, and isolated pockets of Shropshire speak Welsh today.

The regular consonantal sound changes from Proto-Celtic to Welsh, Cornish, and Breton are summarised in the following table. Where the graphemes have a different value from the corresponding IPA symbols, the IPA equivalent is indicated between slashes. V represents a vowel; C represents a consonant.

| Proto-Celtic | Late Brittonic | Welsh | Cornish | Breton |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *b- | *b- | b | b | b |

| *-bb- | *-b- | b | b | b |

| *-VbV- | *-VβV- > -VvV- | f /v/ | v | v |

| *d- | *d- | d | d | d |

| *-dd- | *-d- | d | d | d |

| *-VdV- | *-VðV- | dd /ð/ | dh /ð/ | z /z/ or lost |

| *g- | *g- | g | g | g |

| *-gg- | *-g- | g | g | g |

| *-VgV- | *-VɣV- > -VjV- | (lost) | (lost) | (lost) |

| *ɸ- | (lost) | (lost) | (lost) | (lost) |

| *-ɸ- | (lost) | (lost) | (lost) | (lost) |

| *-xt- | *-xθ- > -(i)θ | th /θ/ | th /θ/ | zh /z/ or /h/ |

| *j- | *i- | i | i | i |

| *-j | *-ð | -dd /ð/ | -dh /ð/ | -z /z/ or lost |

| *k- | *k- | c /k/ | k | k |

| *-kk- | *-x- | ch /x/ | gh /h/ | c'h /x/ or /h/ |

| *-VkV- | *-g- | g | g | g |

| *kʷ- | *p- | p | p | p |

| *-kʷ- | *-b- | b | b | b |

| *l- | *l- | ll /ɬ/ | l | l |

| *-ll- | *-l- | l | l | l |

| *-VlV- | *-l- | l | l | l |

| *m- | *m- | m | m | m |

| *-mb- | *-mm- | m | m | m |

| *-Cm- | *-m- | m | m | m |

| *-m- | *-β̃- | f /v/, w | v | ñv /-̃v/ |

| *n- | *n- | n | n | n |

| *-n- | *-n- | n | n | n |

| *-nd- | *-nn- | n, nn | n, nn | n, nn |

| *-nt- | *-nt- | nt, nh | nt | nt |

| *-pp- | *-ɸ- > -f- | ff | f | f |

| *r- | *r- | rh /r̥/ | r | r |

| *sr- | *fr- | ffr /fr/ | fr | fr |

| *-r- | *-r- | r | r | r |

| *s- | *h-, s | h, s | h, s | h or lost, s |

| *-s- | *-s- | s | s | s |

| *sl- | *l- | ll /ɬ/ | l | l |

| *sm- | *m- | m | m | m |

| *sn- | *n- | n | n | n |

| *sɸ- | *f- | ff /f/ | f | f |

| *sw- | *hw- | chw /xw/ | hw /ʍ/ | c'ho /xw/ |

| *t | *t | t | t | t |

| *-t- | *-d- | d | d | d |

| *-tt- | *-θ- | th /θ/ | th /θ/ | zh /z/ or /h/ |

| *w- | *ˠw- > ɣw- > gw- | gw | gw | gw |

| *-VwV- | *-w- | w | w | w |

| *-V | *-Vh | Vch /Vx/ | Vgh /Vh/ | Vc'h /Vx/ or /Vh/ |

Remnants in England, Scotland and Ireland

Place names and river names

The principal legacy left behind in those territories from which the Brittonic languages were displaced is that of toponyms (place names) and hydronyms (river names). There are many Brittonic place names in lowland Scotland and in the parts of England where it is agreed that substantial Brittonic speakers remained (Brittonic names, apart from those of the former Romano-British towns, are scarce over most of England). Names derived (sometimes indirectly) from Brittonic include London, Penicuik, Perth, Aberdeen, York, Dorchester, Dover and Colchester.[18] Brittonic elements found in England include bre- and bal- for hills, while some such as combe or coomb(e) for a small deep valley and tor for a hill are examples of Brittonic words that were borrowed into English. Others reflect the presence of Britons such as Dumbarton – from the Scottish Gaelic Dùn Breatainn meaning "Fort of the Britons", or Walton meaning a tun or settlement where the Wealh "Britons" still lived.

The number of Celtic river names in England generally increases from east to west, a map showing these being given by Jackson. These names include ones such as Avon, Chew, Frome, Axe, Brue and Exe, but also river names containing the elements "der-/dar-/dur-" and "-went" e.g. "Derwent, Darwen, Deer, Adur, Dour, Darent, Went". These names exhibit multiple different Celtic roots. One is *dubri- "water" [Bret. "dour", C. "dowr", W. "dŵr"], also found in the place-name "Dover" (attested in the Roman period as "Dubrīs"); this is the source of rivers named "Dour". Another is *deru̯o- "oak" or "true" [Bret. "derv", C. "derow", W. "derw"], coupled with 2 agent suffixes, *-ent- and *-iū; this is the origin of "Derwent", " Darent" and "Darwen" (attested in the Roman period as "Deru̯entiō"). The final root to be examined is "went". In Roman Britain, there were three tribal capitals named "U̯entā" (modern Winchester, Caerwent and Caistor St Edmunds), whose meaning was 'place, town'.[19]

Brittonicisms in English

Some, including J. R. R. Tolkien, have argued that Celtic has acted as a substrate to English for both the lexicon and syntax. It is generally accepted that Brittonic effects on English are lexically few aside from toponyms, consisting of a small number of domestic and geographical words, which may include bin, brock, carr, comb, crag and tor.[20][21][22] Another legacy may be the sheep-counting system Yan Tan Tethera in the west, in the traditionally Celtic areas of England such as Cumbria. Several Cornish mining words are still in use in English language mining terminology, such as costean, gunnies, and vug.[23]

Those who argue against the theory of a more significant Brittonic influence than is widely accepted point out that many toponyms have no semantic continuation from the Brittonic language. A notable example is Avon which comes from the Celtic term for river abona[24] or the Welsh term for river, afon, but was used by the English as a personal name.[25] Likewise the River Ouse, Yorkshire contains the word usa which merely means 'water'[26] and the name of the river Trent simply comes from the Welsh word for a trespasser (an over-flowing river).[27]

It has been argued that the use of periphrastic constructions (using auxiliary verbs such as do and be in the continuous/progressive) in the English verb, which is more widespread than in the other Germanic languages, is traceable to Brittonic influence. Others, however, find this unlikely due to the fact that many of these forms are only attested in the later Middle English period; these scholars claim a native English development rather than Celtic influence.[28] Ian G. Roberts postulates Northern Germanic influence, despite such constructions not existing in Norse.[29] Literary Welsh has the simple present Caraf = I love and the present stative (al. continuous/progressive) Yr wyf yn caru = I am loving, where the Brittonic syntax is partly mirrored in English (Note that I am loving comes from older I am a-loving, from still older ich am on luvende "I am in the process of loving"). In the Germanic sister languages of English there is only one form, for example ich liebe in German, though in colloquial usage in some German dialects, a progressive aspect form has evolved which is formally similar to those found in Celtic languages, and somewhat less similar to the Modern English form, e.g. "I am working" is ich bin am Arbeiten, literally: "I am on the working". The same structure is also found in modern Dutch (ik ben aan het werk), alongside other structures (e.g. ik zit te werken, lit. "I sit to working"). These parallel developments suggest that the English progressive is not necessarily due to Celtic influence; moreover, the native English development of the structure can be traced over 1000 years and more of English literature.

Some researchers (Filppula et al., 2001) argue that other elements of English syntax reflect Brittonic influences.[27][30] For instance, in English tag questions, the form of the tag depends on the verb form in the main statement (aren't I?, isn't he?, won't we? etc.). The German nicht wahr? and the French n'est-ce pas?, by contrast, are fixed forms which can be used with almost any main statement. It has been claimed that the English system has been borrowed from Brittonic, since Welsh tag questions vary in almost exactly the same way.[27][30]

Brittonic effect on the Goidelic languages

Far more notable, but less well known, are Brittonic influences on Scottish Gaelic, though Scottish and Irish Gaelic, with their wider range of preposition-based periphastic constructions, suggest that such constructions descend from their common Celtic heritage. Scottish Gaelic contains several P-Celtic loanwords, but as there is a far greater overlap in terms of Celtic vocabulary, than with English, it is not always possible to disentangle P- and Q-Celtic words. However some common words such as monadh = Welsh mynydd, Cumbric *monidh are particularly evident.

Often the Brittonic influence on Scots Gaelic is indicated by considering Irish language usage, which is not likely to have been influenced so much by Brittonic. In particular, the word srath (anglicised as "Strath") is a native Goidelic word, but its usage appears to have been modified by the Brittonic cognate ystrad whose meaning is slightly different. The effect on Irish has been the loan from British of many Latin-derived words. This has been associated with the Christianisation of Ireland from Britain.

References

Notes

- History of English: A Sketch of the Origin and Development of the English Language. Macmillan. 1893. Retrieved 2013-07-07 – via Internet Archive.

- "Brythonic, adj. and n.". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. June 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- Jackson, p. 3.

- "Brittonic, adj. and n.". OED Online. Oxford University Press. June 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 305. ISBN 1851094407. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 306. ISBN 1851094407. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Britain". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Chadwick, Hector Munro, Early Scotland: The Picts, the Scots and the Welsh of Southern Scotland, Cambridge University Press, 1949 (2013 reprint), p. 68

- Cunliffe, Barry (2012). Britain Begins. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 4.

- Rivet, A; Smith, C (1979). The place names of Roman Britain. B.T. Batsford. ISBN 978-0713420777

- Brown, Ian (2007). The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: From Columba to the Union (until 1707). Edinburgh University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7486-1615-2. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- Jackson, 1955

- Driscoll, 2011

- Koch, John T. (2007). An Atlas for Celtic Studies. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-309-1.

- R. Fleming, Britain After Rome (2011), p. 45-119.

- H. Tristram, "Why Don't the English Speak Welsh? Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine", in Higham (ed.), Britons in Anglo-Saxon England (2007), p. 192-214.

- D. White, "On the Areal Pattern of 'Brittonicity' in English and Its Implications" (Austin, Texas, 2010).

- op. cit.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic, p. 413. Brill, Leiden-Boston. ISBN 978-90-04-17336-1

- Coates, Richard, ‘Invisible Britons: The View from Linguistics’, in Britons in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Nick Higham, Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies, 7 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007), pp. 172–91 (pp. 177-80).

- Kastovsky, Dieter, ‘Semantics and Vocabulary’, in The Cambridge History of the English Language, Volume 1: The Beginnings to 1066, ed. by Richard M. Hogg (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 290–408 (pp. 318-19).

- D. Gary Miller, External Influences on English: From Its Beginnings to the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 19–20.

- Dictionary of Mining, Mineral, and Related Terms by American Geological Institute and U S Bureau of Mines (pages 128, 249, and 613)

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Coates, Richard, ‘Invisible Britons: The View from Linguistics’, in Britons in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. by Nick Higham, Publications of the Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies, 7 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007), pp. 172–91 (pp. 177-80).

- A. Room (ed.) 1992: Brewer's Dictionary of Names, Oxford: Helicon, p. 396-7.

- Hickey, Raymond. 'Early Contact And Parallels Between English and Celtic.' in 'Vienna English Working Papers'.

- John Insley, "Britons and Anglo-Saxons," in Kulturelle Integration und Personnenamen in Mittelalter, De Gruyter (2018)

- Roberts, Ian G. Verbs and diachronic syntax: a comparative history of English and French Volume 28 of Studies in natural language and linguistic theory Volume 28 of NATO Asi Series. Series C, Mathematical and Physical Science.

- van Gelderen, Elly. A History of the English Language.

Sources

- Aleini M (1996). Origini delle lingue d'Europa.

- Dillon M and Chadwick N (1967). Celtic Realms.

- Filppula, M., Klemola, J. and Pitkänen, H. (2001). The Celtic roots of English, Studies in languages, No. 37, University of Joensuu, Faculty of Humanities, ISBN 952-458-164-7.

- Hawkes, J. (1973). The first great civilizations: life in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley and Egypt, The history of human society series, London: Hutchinson, ISBN 0-09-116580-6.

- Jackson, K., (1994). Language and history in early Britain: a chronological survey of the Brittonic languages, 1st to 12th c. A. D, Celtic studies series, Dublin: Four Courts Press, ISBN 1-85182-140-6.

- Jackson, K. (1955), "The Pictish Language", in Wainwright, F.T., The Problem of the Picts, Edinburgh: Nelson, pp. 129–166

- Rivet A and Smith C (1979). The Placenames of Roman Britain.

- Schrijver, P. (1995), Studies in British Celtic Historical Phonology. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-820-4.

- Willis, David. 2009. "Old and Middle Welsh". In Ball, Martin J., Müller, Nicole (ed). The Celtic Languages, 117–160, 2nd Edition. Routledge Language Family Series.New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-88248-2.

- Driscoll, S T 2011. Pictish archaeology: persistent problems and structural solutions. In Driscoll, S T, Geddes, J and Hall, M A (eds) Pictish Progress: new studies on northern Britain in the early Middle Ages, Leiden and Boston: Bril pp 245–279.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Brythonic Celtic Languages Division |

- Coates, Richard (2007) Invisible Britons: the view from linguistics. (archived)