Cadereyta Jiménez massacre

The Cadereyta Jiménez massacre occurred on the Fed 40 on 12–13 May 2012.[1] Mexican officials stated that 49 people were decapitated and mutilated by members of Los Zetas drug cartel and dumped by a roadside near the city of Monterrey in northern Mexico.[2][3] The Blog del Narco, a blog that documents events and people of the Mexican Drug War anonymously, reported that the actual (unofficial) death toll may be more than 68 people.[4] The bodies were found in the town of San Juan in the municipality of Cadereyta Jiménez, Nuevo León at about 4 a.m. on a non-toll highway leading to Reynosa, Tamaulipas.[5][6] The forty-three men and six women killed had their heads, feet, and hands cut off, making their identification difficult.[2] Those killed also bore signs of torture and were stuffed in plastic bags.[7] The arrested suspects have indicated that the victims were Gulf Cartel members,[8] but the Mexican authorities have not ruled out the possibility that they were U.S.-bound migrants.[9] Four days before this incident, 18 people were found decapitated and dismembered near Mexico's second largest city, Guadalajara.[10]

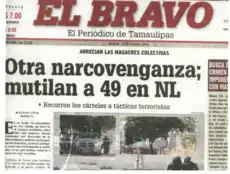

| Cadereyta Jiménez massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of Mexican Drug War | |

Expreso front page on 14 May 2012 | |

| Location | Cadereyta Jiménez, Nuevo León, Mexico |

| Date | 12–13 May 2012 |

Attack type | Mass murder |

| Deaths | 49 |

| Victim | Unsure[N 1] |

| Perpetrators | Los Zetas |

The metropolitan area of Monterrey is an important warehousing center for cocaine, marijuana and other illegal drugs bound for U.S. consumers.[11] The natural gas wells and pipelines running through Cadereyta and the U.S-Mexico border have also been the most tapped by thieves, supplying gasoline and other natural resources to Mexico's criminal underworld. Small towns, ranches, and isolated communities in Nuevo León have long been treasured by drug traffickers.[11] The Mexican drug trafficking organizations have been fighting for the territorial control of the smuggling routes to the United States, and this massacre may be the "latest blow in an escalating war of intimidation among drug gangs."[12] The cartels also fight for the control of local drug markets and extortion rackets, including shakedowns of migrants seeking to reach the United States.[13] In addition, the discovery seems to echo several other mass murder events where the drug cartels have left large numbers of bodies in public places as warnings to their rivals.[14] The authorities have blamed much of the violence on Los Zetas – a cartel originally set up by ex-commandos that deserted the Mexican Army in the 1990s – and the Sinaloa Cartel, an organization originally headed by Joaquín Guzmán Loera (a.k.a. El Chapo), once Mexico's most-wanted drug lord.[15][16]

Background

Gang rivalry

Since 2011, Los Zetas and the Sinaloa cartel have emerged as the two main criminal syndicates in Mexico's drug war, with smaller gangs lining up on either side in a competition that now resembles a "full-scale war."[17] A string of mass slayings have convulsed Mexico in 2011 and 2012. Many of them took place in northern states, where Los Zetas have waged a war against rival drug trafficking organizations for the control of the smuggling routes into the United States.[18] The Los Zetas gang dates back to 1999, when deserters of the Mexican Army Special Forces joined the ranks of the Gulf Cartel. Nonetheless, the two organizations split in early 2010, and have fought for the control of the trafficking routes since then. The powerful Sinaloa Cartel, the Zetas' mortal rivals, has stood up and fought Los Zetas too.[18] Since late April 2012, Los Zetas has been under immense pressure by the alliance between the Gulf cartel and the Sinaloa cartel.[19] In March 2012, thirteen Los Zetas' members were killed and dismembered by the Sinaloa Cartel in a turf war; Los Zetas responded in kind, killing at least 10 members of the Sinaloa cartel in their rival's turf.[19]

Much of the violence between Los Zetas and the Sinaloa cartel is the result of fighting over cocaine supplies from South America.[20] On the supply side, the increased pressures on Sinaloa kingpin Joaquín Guzmán Loera, whose operations in Colombia in 2012 prompted his organization to grab larger shares of cocaine from Peru and Ecuador, threatened the supply-lines of Los Zetas, and triggered tit-for-tat attacks among both cartels.[20] The Sinaloa cartel and Los Zetas are "regional and cultural opposites," because the Sinaloa organization has been moving drugs north from the ranch country parts in Mexico into the U.S. for generations, while Los Zetas are newer arrivals from the more urban eastern coast.[21] In addition, Los Zetas is a transient cartel without real territory or a secure stream of income, while the Sinaloa Cartel has a lucrative cocaine trade and the control of smuggling routes and territories. But the former are heavily armed, while the latter's enforcement arm is weaker.[22] The Sinaloa cartel uses tit-for-tat attacks as a way of bringing down the newcomers; for Los Zetas, it is about maintaining their violent reputation – the organization's most valued asset.[21] Moreover, Los Zetas pose a bigger insurgency threat to the Mexican government than the older cartels in the country because of the brutality of their attacks against the security forces, their disregard for civilians' lives, and their dangerous habits that go beyond the "unspoken codes of older traffickers." The violent reputation of Los Zetas has made northeastern Mexico a no-go zone for many.[23] Los Zetas, unlike the other traditional drug cartels, act like urban guerrillas; a police chief in Mexico explained how the Zetas would make anonymous phone calls to get the police out in the streets, block the road where the police were, and then open fire from all sides.[23] In addition, the goal of Los Zetas differs greatly from other drug trafficking organizations in Mexico. Other cartels focus primarily in drug producing and drug trafficking, while Los Zetas often move into urban areas to diversify their criminal agenda and carry out a number of crimes.[23] Their presence represents a new model for organize crime, unseating many older cartels with their brutal violent tactics that destabilize Mexico.[23]

The drug violence in the state of Nuevo León and all across Mexico has left more than 50,000 people dead since President Felipe Calderón took office in 2006.[24] His military-led approach shortly after taking office spiraled the violence in the country, and has eroded the support of Calderon's conservative National Action Party (PAN), which did not regain the presidential seat in the 2012 presidential elections.[24] The city of Monterrey was long been a bastion of the PAN, and the local business community has been "livid" about the violence in their city. Surveys showed that voters thought that the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which ruled Mexico uninterruptedly from 1929 to 2000, is likely to control and put down the violence. Its 71-year rule was "tainted by corruption," and critics have accused the PRI of making deals with the cartels to maintain peace in the country.[24]

Modus operandi

In the 1990s, the drug cartels in Mexico did not cut off the heads of the victims.[25] Instead, they used different "codes of murder" established between the mafias. A bullet through the back of the head, for example, signified that the victim was a traitor; a bullet through the temple, however, signified that the victim was member of a rival drug gang.[25] Now, decapitation is a tactic often used by the criminal organizations in Mexico—primarily by Los Zetas and its two main rivals, the Gulf and Sinaloa cartels. The first public decapitation was carried out by La Familia Michoacana in September 2006, when several gunmen opened the doors of a bar in the Mexican state of Michoacán and threw five severed heads on the dance floor.[25] The practices of beheading victims in Mexico is believed to have come from Guatemala in the year 2000, when Los Zetas extended their criminal network into Central America and eventually incorporated with the elite jungle military squad known as the Kaibiles.[26] The Kaibiles had been trained to intimidate the local population with beheadings during the Guatemalan Civil War (1960–1996).[26] Others see the link with the religious cult of the Santa Muerte ("Holy Death").[26] Wherever it stems from, decapitations is "now a staple in the lexicon of violence" in the Mexican Drug War.[26]

Intended to terrorize the civil population and intimidate rival cartels, the public display of butchered bodies has replaced the traditional Mexican drug cartel practice of burying people in clandestine mass graves, as in the municipality of San Fernando, Tamaulipas.[27] These new cartel tactics were used for the first time by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel in September 2011 when they dumped over 30 bodies on a busy avenue in the state of Veracruz.[27] Los Zetas, however, responded with their own butchery by leaving 26 corpses in the state of Jalisco and over a dozen in Sinaloa. These kinds of tactics are media measures taken by organized crime to solicit the attention of the public and their rival groups.[27] In earlier instances, some of the victims turned out to be students, bakers, and brick layers—none of them with criminal records. In effect, anyone who can be abducted from the streets is fair game for use in these mass slayings designed to "cause terror."[17] Moreover, the new tactic of leaving huge body dumps may be used by the cartels to draw law enforcement into a territory to disrupt the activities of a cartel's rival in its home or disputed territory.[17]

The two-year rivalry between Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel has killed thousands of people since early 2010, and has grown increasingly bloody in recent months after the participation of gunmen loyal to Joaquín Guzmán Loera of the Sinaloa cartel. Guzmán, Mexico's most-wanted drug lord, has allied with the Gulf cartel to fight off Los Zetas and take control of their territories.[11] The organized crime groups often leave multiple bodies in public places as warnings to their rivals; these criminal groups have been fighting for the control of the drug corridors to the United States, the local drug markets in cities, extortion rackets, and human smuggling.[28] Violence has erupted in several parts of Mexico between Los Zetas and the Sinaloa Cartel, who fight to take over each other's territories.[29][30]

Cartels' retaliation attacks

On 20 September 2011, violence erupted between Los Zetas and the Sinaloa cartel in Veracruz, a strategic smuggling state with a giant gulf port.[31] Two trucks containing 35 dead bodies were found at an underpass near a shopping mall in Boca del Río,[32] having reportedly been abandoned there by armed men in the middle of the highway.[33][34][35] All of the victims were alleged to be members of Los Zetas,[36] but it was later proven that only six of them had been involved in minor crime incidents, and none of them were involved with organized crime.[37] The Blog del Narco reported on 21 September 2011 that the message left behind was supposedly signed by Gente Nueva, an enforcer group of Joaquín Guzmán Loera, the top boss of the Sinaloa cartel;[38] However, the Jalisco New Generation Cartel also claimed responsibility, and announced they were planning to take over Veracruz.[39] On 6 October 2011, again in Boca del Río, 32 bodies were found by the Mexican authorities in three different houses.[40][41] Four further bodies were confirmed separately by the state government of Veracruz.[42] The discoveries led to the resignation of Reynaldo Escobar Pérez, the State Justice Attorney General.[43] One day after the resignation, 10 more bodies were found throughout the city of Veracruz.[44] The Jalisco New Generation Cartel was also responsible for 67 killings in Veracruz on 7 October 2011.[45]

Los Zetas retaliated against their enemies in the state of Sinaloa on 23 November 2011 and left 26 bodies in several abandoned vehicles in Sinaloa.[46][47] In the early hours of the morning in Culiacán, Sinaloa, they had set a vehicle ablaze.[48] A dozen charred and handcuffed bodies were in the vehicle.[48] At 07:00 hours, another burning vehicle was discovered in the northern city limits of Culiacán, inside which were four bodies handcuffed and clad in bulletproof vests.[48] During the night, 10 more bodies were found throughout several different municipalities.[48] As a response to the Sinaloa cartel incursions in Veracruz, Los Zetas carried out reprisal killings in the Guadalajara.[49][50] On 24 November 2011, three trucks containing 26 bodies were found in an avenue at Guadalajara.[51] At around 7:00 pm, Guadalajara police received numerous reports of vehicles abandoned in a major avenue with more than 10 bodies.[52] Reports identified twenty-six victims as alleged Sinaloa Cartel members, and mentioned that Los Zetas and the Milenio Cartel were responsible for their massacre.[53]

Dismembered remains of 14 men were found in several plastic bags inside two vehicles in the border city of Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, on 17 April 2012.[54] CNNMéxico stated that the message left behind by the criminal group said that they were going to "clean up Nuevo Laredo" by killing Zeta members.[55] The Monitor newspaper, however, cited a source with direct knowledge of the attacks stating the 14 bodies belonged to members of Los Zetas who had been killed by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, now a branch of the Sinaloa Cartel.[56] Following the attacks, Joaquín Guzmán Loera – better known as El Chapo Guzmán – sent a message to Los Zetas that they would fight for the control of the Nuevo Laredo plaza.[57] At around 1:00 am on 4 May 2012, nine people were hanged from a bridge on the Fed 85D in Nuevo Laredo.[58] A banner left behind reportedly stated that those killed were the perpetrators of the car bomb in the city on 24 April 2012.[59] The nine were reportedly members of the Gulf Cartel who were killed by Los Zetas.[60] Several hours later, 14 decapitated bodies were abandoned inside a vehicle in front of the Customs Agency;[61] the severed heads were left inside several ice coolers in front of the municipal palace.[61] The Mexican police said the second massacre could have been an act of revenge by the Gulf Cartel against Los Zetas for the earlier killings.[62][63] The decapitated bodies were found with a message allegedly signed by Joaquín Guzmán Loera, demanding recognition presence of the Sinaloa cartel in the area.[64]

In the morning on 9 May 2012,[65] Los Zetas left the chopped-up remains of 18 bodies inside two vehicles in Chapala, Jalisco, just south of Guadalajara.[66][67][68] Eighteen heads were found along the dismembered bodies; some had been frozen, others were covered in lime, and the rest were found in an advanced state of decomposition.[69] The Mexican authorities confirmed that a message was left behind by the killers, presumably from Los Zetas and the Milenio Cartel.[68]

Investigations

In 2012, the state of Nuevo León and its surrounding territories have become a battleground for a brutal conflict between Los Zetas and the Gulf Cartel, two drug trafficking organizations from northeastern Mexico.[70] Reports of forced disappearances have not been uncommon in the past years. The municipality of Cadereyta Jiménez – a middle-class, industrial community where the bodies were found – is known for its broom factory, an oil refinery, and its historical role as one of the first places where baseball was played in Mexico.[70] Nonetheless, it had at least five municipal employees slain in April 2012; just a week before the massacre, a military general stepped up and took over the city's depleted police force.[70] In fact, the municipality of Cadereyta Jiménez is under dispute by Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel, and the Sinaloa Cartel;[71] the area is a strategic point for human smuggling, drug trafficking, and oil theft.[71] The municipality of Cadereyta is the most violent municipality in the state of Nuevo León that does not form part of the Monterrey metropolitan area.[72]

Initially, the Mexican authorities reported the discovery of 37 bodies early in the morning on 13 May 2012 in the town of San Juan, 75 miles (125 km) southwest of the border city of Roma, Texas.[73] However, upon more detailed examination at the scene, the official figures reached 49 dead.[74] The bodies were discovered on the Mexican Federal Highway 40 at about 4 am, forcing the Mexican police and the federal troops to close the highway.[73] The victims were all headless and dismembered;[75][76][77] none of the victims were shot dead.[78] According to the testimonies of several civilians from San Juan, late at night before the bodies were discovered, a foul-odor could be perceived from a distance, but none of them imagined that the stink actually came from dismembered bodies.[79] When the forensic experts began to pick up the bodies, they had to use facemasks because the intensity of the odor was intolerable.[79] The Mexican authorities in the area had to cover their mouths and noses for the same reason.[80]

The attorney's office declared that the victims were dismembered to prevent them from being identified.[81] Nonetheless, the victims are believed to be more than 25 years of age,[82] and many of them had tattoos of the Santa Muerte ("Holy Death") – a female skeletal grim reaper – which could facilitate their identification.[77] The bodies were taken to the hospital in the University of Monterrey for DNA testing and further investigation;[9][83] dozens of military men were ordered to guard the surrounding area.[83] Nuevo León's security spokesman said that the 49 people were killed up to 48 hours earlier at a different location, most likely in the neighboring state of Tamaulipas,[84] and then transported by truck to where they were found.[85] In addition, he said at a news conference that a banner left at the site bore a message with Los Zetas claiming responsibility for the killing.[86] A large black "Z 100%" was spray-painted on a road sign close to where the bodies were found.[87] The Mexican police have taken this spray-painted message as a reference to Los Zetas, which often leaves messages signed "Z" at crime scenes to intimidate both authorities and rivals.[88]

The authorities noted that there had been no forced disappearances in the area in the previous days,[89] and so did not discount the possibility that those killed were US-bound migrants.[86] Univision suggested that, due to the large numbers of people in this massacre, those killed may have been illegal migrants who were abducted from a bus in which they were traveling and then killed by Los Zetas for failing to pay the 'cuota'.[85] The authorities have also not discarded the possibility that the massacre was the result of an "internal adjustment" between the Mexican criminal organizations.[90] Javier Del Real, the secretary of Public Safety in the state, mentioned that the purpose of the massacre was to bring people's attention, "and it did."[90]

El Salvador asked Mexico for the DNA results of the victims in Cadereyta to make sure if those killed were migrants from their country,[91] but as of July 2012, none of the bodies have been identified.[92]

Aftermath

Soon after the massacre, more than 50 police officers guarded the municipality of Cadereyta.[93] And for more than seven hours, the stretch of Mexican Federal Highway 40 where the massacre occurred was blocked by federal agents and state police officers.[94]

The Attorney General of Mexico (PGR) attributed the escalating violence in the country to the criminal organizations headed by Joaquín Guzmán Loera (a.k.a. El Chapo) and Ismael Zambada García (a.k.a. El Mayo), who head the Sinaloa cartel; and to Heriberto Lazcano Lazcano (a.k.a. El Lazca) and Miguel Treviño Morales (a.k.a. Z-40), who used to head Los Zetas drug cartel.[95] According to the Mexican government, the two cartels have committed "irrational acts of inhumane and inadmissible violence in their dispute" and have created "the most definitive of all the cartel wars" in Mexico.[96] The Mexican government offers up to 30 million pesos ($2 million U.S. dollars) for information that leads to the capture of these mafia bosses.[96][97]

The Mexican federal government issued a statement on 13 May 2012 condemning the attacks.[98] The Secretaría de Gobernación (Segob) offered its support to aid the authorities of the state of Nuevo León to find those responsible. The municipal authorities of the state were also asked to maintain coordination and work in unison with the Federal government.[98] The Mexican authorities then asked the population to stay calm, since the massacre took place in a remote area and in the darkness of the early morning.[99] In addition, SEGOB emphasised that as for the Monterrey casino attack and the San Fernando massacre, justice would be served.[100]

YouTube video

A Blog del Narco article on 15 May 2012 pointed to a video recording uploaded on YouTube showing several members of Los Zetas disposing of the butchered bodies on the highway in Cadereyta.[101] The video, recorded by an anonymous man who at the same time gave instructions to his henchmen, lasts for about 7 minutes.[101] It shows how the bodies were transported by a dump truck to the area where they were found; once the truck stopped, several young men dumped the bodies on the highway one by one.[101] Over the dark scene in the videotape, a voice was heard on the background yelling: "How many are left? How many are left?"[102] Alongside the bodies, they placed a banner:

"This is going to happen to all the Gulf and Sinaloa cartel members; the Mexican marines; Federal police; and government forces. No one can stop us. Sincerely, The Crazy, Miguel Treviño Morales (Z-40), and Commander Heriberto Lazcano."[101]

— Los Zetas

'Narco-banners' from Los Zetas

On 15 May 2012 Los Zetas allegedly put up five narco-banners from bridges or in other public places of San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas[103] denying responsibility for the Cadereyta Jiménez massacre.[104] Other banners were also put up in Monterrey and Nuevo Laredo.[105][106] In the written banners, Los Zetas disassociated themselves from the slaughter in Nuevo León, and asked the Mexican federal government to conduct an investigation before blaming them.[107] The banners suggested that the massacre was perpetrated by the Gulf Cartel, saying that Los Zetas would have dumped the bodies inside the city of Reynosa, Tamaulipas (within the territory of the Gulf cartel), instead of in Cadereyta Jiménez, Nuevo León, its own territory;[108] Los Zetas, however, assumed responsibility for the 18 killed in Jalisco and the 9 hanged in Nuevo Laredo.[109] The banners were immediately removed by the Mexican authorities.[110] The authorities stated that they have not formally accused Los Zetas for carrying out the massacre, and that they only stated the content of the banners found alongside the bodies.[111]

It was later proven that Los Zetas put up the banners to confuse the authorities of their involvement in the massacre.[112]

Arrests

The Mexican military detained eight Gulf Cartel members in the small, northeastern town of China, Nuevo León on 17 May 2012.[113] Officials of the Secretariat of National Defense stated that the cartel members were captured during a military operation in the area in which cocaine was allegedly seized.[114] The detainees were initially believed to have been involved in the dumping of 49 mutilated corpses in Cadereyta.[115] The massacre was viewed as an attempt by the Gulf Cartel to stoke law enforcement crackdown in Los Zetas territory – a tactic known as "heating up the plaza."[116] Nonetheless, the Mexican authorities later confirmed that the actual perpetrator of the massacre was Los Zetas, and not the Gulf cartel.[117]

After the discovery of the 49 corpses, the Mexican military implemented "Operation Rastrillo" to coordinate the regional commanders in the states bordering Nuevo León to seal and prevent the movement of offenders into other areas of the region.[118] In Guadalupe, Nuevo León on 18 May 2012, the operation led to the capture of Jesús Daniel Elizondo Ramírez, nicknamed El Loco (English: "The Crazy One"), a member of the Los Zetas.[119][120][121] El Loco was the leader of an important cell within the Los Zetas that was responsible for the massacre.[119] According to the authorities, El Loco joined group of hitmen in 2008 that was looking to expand the presence of Los Zetas in Guatemala; during his time in Guatemala, he engaged in many armed confrontations with local drug traffickers, including one that killed Juan José León Ardón alias El Juancho, one of the country's most-wanted drug lords.[122] He is also responsible for several kidnappings and assassinations in Cadereyta, along with the murder of the Secretary of Social Development of the state.[123] The Mexican authorities confirmed on 21 May 2012 that Daniel Elizondo El Loco was given orders by Heriberto Lazcano and Miguel Treviño Morales to carry out the massacre in Cadereyta to "cause confusion" among the population and the authorities.[122] Elizondo, however, disobeyed the orders of his leaders and dumped the bodies in the Mexican Federal Highway 40 instead of dumping them in Cadereyta's main public square, where it was previously planned.[122] The bodies were transported from Los Herrera to Cadereyta, two municipalities between the city of Monterrey and the Rio Grande, and then dumped on the highway by Elizondo and 30 other gunmen.[124]

Upon the arrests of 17 May 2012, the Mexican military obtained information of the existence of five clandestine graves in China, Nuevo León.[125] The five individual graves, at a ranch known as 'La Gloria' just on the border with Tamaulipas and identified by members of Los Zetas, were exhumed by the authorities.[126][127][128] The authorities, however, said that the corpses found were "complete skeletons," ruling out the possibility of them being the victims of the Cadereyta massacre.[125] The bodies were calcined and in an advance state of decomposition.[128]

In the city of Santa Catarina, Nuevo León, the Mexican Navy arrested José Ricardo Barajas López on 3 August 2012, another cartel member responsible for the massacre. He is one of the 37 fugitives that escaped during the Apodaca prison riot in February 2012, where 44 Gulf Cartel inmates were killed.[129] According to the Mexican authorities, Barajas López delivered the 49 alleged Gulf Cartel members to a man known as Tula, who forward the victims to Rolando Fernando Sánchez González, a former policeman and the regional boss of Los Zetas in Santa Catarina, for execution.[130]

Two months after the arrests, the Mexican authorities have not been able to identify the victims of the massacre. Hence, the bodies will most likely be sent to local cemeteries, although many civil organizations protested against this.[92][131]

Notes

- The suspects arrested claim that the victims were members of the Gulf Cartel, a rival drug trafficking organization. Nonetheless, the Mexican authorities have not discarded the possibility that the victims were U.S-bound migrants.

References

- "Official: 49 bodies left on Reynosa-Monterrey highway". The Monitor. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Official: 49 bodies left on Mexico highway". Yahoo! News. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mexico violence: Monterrey police find 49 bodies". BBC News. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Masacran a 68 personas en Nuevo León". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "49 bodies dumped on Mexican highway". CBS News. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Autoridades hallan 49 cadáveres en una carretera de Nuevo León". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "49 bodies left on Mexican highway". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mexican army captures suspect in slaughter of 49 people". Fox News. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- "Dozens of bodies, some mutilated, dumped on Mexico highway". Fox News. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Scores of mutilated bodies dumped on Mexico highway". BBC News. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Nearly 50 bodies recovered from latest Mexico massacre". Houston Chronicle. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mexican officials report 49 bodies dumped on highway to US border". Yahoo! News. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mexican police find 49 bodies dumped on highway". MSN News. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Discovery of mutilated bodies shuts down Reynosa, Monterrey highway". KGBT-TV. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mexican police find 49 mutilated bodies". Agence France-Presse. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Dozens of bodies found in bags". Herald Sun. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "49 headless bodies unidentified in Mexico massacre". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Forty-nine headless corpses found in northern Mexico". Orlando Sentinel. 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Cadereyta massacre was part of Los Zetas Mothers Day plot". Borderland Beat. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "49 headless bodies dumped near Mexican highway". Toronto Star. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Archibold, Randal C. (15 May 2012). "Numb to Carnage, Mexicans Find Diversions, and Life Goes On". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- "Mexico's 49 Headless Bodies is Third Massacre in 10 Days in 'Triangle of Death'". Fox News. 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Ioan Grillo (23 May 2012). "Special Report - Mexico's Zetas rewrite drug war in blood". Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- "Forty-nine headless corpses found in northern Mexico". Yahoo! News. 14 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- "Fear and intimidation". Borderland Beat. 15 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Grant, Will (15 May 2012). "Mexico violence: Fear and intimidation". BBC News. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Althaus, Dudley (13 May 2012). "49 bodies dumped on Mexico highway". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "49 bodies left on Mexican highway". Brisbane Times. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mexican officials report 49 bodies dumped on highway to US border". The Washington Post. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Rodriguez, Olga (14 May 2012). "49 headless bodies dumped on north Mexico highway". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "49 bodies with heads, hands and feet chopped off found on Mexican highway leading to US border". The Washington Post. 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "35 bodies found in Mexican roadway during rush hour". CNN. 20 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012.

- "Veracruz: tiran a 35 ejecutados en zona turística". El Universal (in Spanish). 21 September 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Castillo, Eduardo (21 September 2011). "Mexico Horror: Suspected Drug Traffickers Dump 35 Bodies on Avenue in Veracruz". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Arrojan 35 cuerpos torturados en una calle de Veracruz". El Mundo (in Spanish). 21 September 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "35 muertos de Boca del Río serían Zetas: Autoridades". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 21 September 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- Martínez, Chivis (8 June 2012). "Bodies of Innocents Used as Props in Mexico's Drug War". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 16 June 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Booth, William (21 September 2011). "35 bodies dumped in Mexican city as president begins effort to woo tourists". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Comando armado se responsabiliza por cádaveres arrojados en Veracruz". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 27 September 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "Marina reporta el hallazgo de 32 cuerpos en Veracruz; la Procuraduría, 4". CNN Mexico (in Spanish). 6 October 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mexico: 32 Bodies Are Found in Veracruz Houses". Los Angeles Times. 7 October 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Son 36 los cadáveres hallados en Veracruz". Televisa (in Spanish). 7 October 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "El procurador de Veracruz renuncia a su cargo tras una ola de violencia". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 7 October 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Soberanes, Rodrigo (8 October 2011). "Otros 10 cadáveres son encontrados en el estado de Veracruz". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- "Caen 'Matazetas' ligados a cadáveres en Veracruz". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 7 October 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "Mexico Security Memo: Los Zetas Strike in Sinaloa Territory". Stratfor. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "Las autoridades de Sinaloa localizan 23 cadáveres en tres municipios". CNN Mexico (in Spanish). 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- "26 muertos en Sinaloa; 16 fueron calcinados". El Universal (in Spanish). 24 November 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Ligan al cártel del Milenio-Z con hallazgo de 26 cuerpos en Guadalajara". Proceso (in Spanish). 24 November 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "Guadalajara: Posible guerra Zetas-cartel Sinaloa deja 26 muertos". Yahoo News (in Spanish). 24 November 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "26 cadáveres son abandonados en camionetas, en una avenida de Guadalajara". CNN Mexico (in Spanish). 24 November 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- "Hallan al menos 20 cadáveres en Guadalajara". El Universal (in Spanish). 24 November 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "El Cártel del Milenio y Los Zetas se atribuyen masacre en Guadalajara". Univision (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Mexico authorities say bodies of 14 men dumped in Nuevo Laredo". Los Angeles Times. 17 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "14 cuerpos mutilados fueron hallados en Nuevo Laredo". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 17 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "14 bodies found in minivan outside Nuevo Laredo City Hall, according to Tamps. gov't". The Monitor. 17 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "El Chapo demuestra su poder en Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "Los cuerpos de 23 personas son encontrados en Nuevo Laredo". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Nuevo Laredo vive un viernes negro, jornada violenta deja 23 muertos". Excélsior (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Suman 23 muertos en Nuevo Laredo, entre colgados y decapitados". Univision (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Van 23 muertos en Nuevo Laredo, en ola de violencia". El Universal (in Spanish). 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Bodies of 23 found dumped near U.S. border in Mexico drug war". Yahoo! News. 4 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- "Se recrudece violencia en Nuevo Laredo: 23 muertos". El Universal (in Spanish). 5 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- "Pide "El Chapo Guzman" al alcalde de Nuevo Laredo que deje de negar su presencia". La Policiaca (in Spanish). 6 May 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Fifteen decapitated in apparent Mexico revenge attack". Yahoo! News. 9 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Narcoviolencia vuelve a Jalisco; hallan 18 cuerpos en dos vehículos". Excélsior (in Spanish). 10 May 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "At least 15 bodies found near U.S. retiree hamlet in Mexico". Los Angeles Times. 9 May 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Dejan a 15 ejecutados en una camioneta en Jalisco". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 9 May 2012. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Looft, Christopher (10 May 2012). "With 18 Killed, Zetas Bring Nuevo Laredo War to Jalisco". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "49 decapitated bodies found in Mexico". CNN. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Gómora, Doris (14 May 2012). "DEA: pelean Cadereyta tres cárteles". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- "Suman 49 cuerpos mutilados en Cadereyta, NL". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Official: 49 bodies left on Mexico highway". Associated Press. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Confirman 49 asesinados en Cadereyta". TV Azteca (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Hallan 49 cuerpos en Cadereyta". El Economista (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- R.Rodriguez, Olga (14 May 2012). "Gangs blamed for 40 Mexico deaths". The Independent. London. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Ochoa, Luis (13 May 2012). "Forty-nine headless corpses found in Mexico". Reuters. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Ninguno de los cuerpos presenta impactos de arma de fuego: Domene". Milenio (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "La noche trajo el olor a muerte". El Universal (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "La noche trajo el olor a muerte". El Mañana (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "La guerra entre cárteles mexicanos deja más de cien muertos en el último mes". La Razón (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Wilkinson, Tracy (13 May 2012). "Dozens of bodies, many mutilated, dumped in Mexico". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Blindan" HU luego de ingresar los cadáveres". Milenio (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Asesinaron en Tamaulipas a los 49 descuartizados hallados en Cadereyta". Proceso (in Spanish). 31 May 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- "Hallaron 49 cuerpos mutilados en Nuevo León". Univision (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Official: 49 bodies left on Mexico highway". Houston Chronicle. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Mutilated bodies dumped on Mexican highway". ABC. 13 May 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Torov, Daniel (14 May 2012). "Mexico: 49 Decapitated Bodies Likely Victims of Drug Cartel Turf War". International Business Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Autoridades investigan si cadáveres encontrados en NL son de migrantes". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Autoridades de NL descartan civiles entre muertos de Cadereyta". El Informador (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "El Salvador pide pruebas de ADN de cuerpos de Cadereyta". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 17 May 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Kane, Michael (24 July 2012). "Two Months on, Nuevo Leon Massacre Victims Remain Unidentified". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Encuentran 49 cuerpos mutilados en Cadereyta". Milenio (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Sin identificar los 49 cuerpos hallados en Cadereyta, NL". Milenio (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "La PGR condena los hechos violentos ocurridos en Nuevo León". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- Rodriguez, Olga R. (14 May 2012). "Mexico drug war's latest toll: 49 headless bodies". The Washington Times. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Advierte gobierno de Calderón que matanza no quedará impune". Proceso (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Tiran en Cadereyta restos de 49 cuerpos". Yahoo! News (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Activan operativo en NL, tras crimen múltiple". El Universal (in Spanish). 13 May 2012. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Masacre en NL no quedará impune: Segob". Milenio (in Spanish). 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "Video: La masacre de Cadereyta, Nuevo León". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 15 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Warner, Margaret (18 June 2012). "The Most Important Presidential Race You Haven't Heard About". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- Ellingwood, Ken (28 October 2008). "Grim glossary of the narco-world". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "Zetas cuelgan mantas en las que se deslindan de la masacre en NL". SDP Noticias (in Spanish). 15 May 2012. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "Narcomantas en NL culpan al CDG de masacre en Cadereyta". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 16 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "También en Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas aparecen narcomantas de los Zetas". La Policiaca (in Spanish). 16 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Los Zetas se deslindan de la masacre de Cadereyta". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 15 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "Texto íntegro de narcomantas firmadas por Los Zetas". Blog del Narco (in Spanish). 15 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- "En narcomantas, se deslindan Zetas de matanza en Cadereyta". Proceso (in Spanish). 15 May 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- "Zetas se deslindan de masacre en Cadereyta en narcomantas". Terra Networks (in Spanish). 15 May 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2012.

- "Al concluir ADN de los 49 cuerpos de Cadereyta, datos serán dados a la PGR". Milenio (in Spanish). 16 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Ellingwood, Ken (21 May 2012). "Mexican army says Zetas behind killing of 49 in northern Mexico". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- "Caen ocho del Cártel del Golfo vinculados a masacre de 49 en NL". Excélsior (in Spanish). 17 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- "8 Drug cartel suspects arrested in Mexico". Fox News. 17 May 2012. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- "Caen ocho del Cártel del Golfo vinculados a masacre de 49 en NL". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 17 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Ramsey, Geoffrey (18 May 2012). "Mexico Arrests 8 'Gulf Cartel Members' over Nuevo Leon Massacre". InSight Crime. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- Mosso, Rubén (22 May 2012). "El Lazca ordenó matanza de NL para culpar al Golfo". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- "Captura Ejército a "El Loco" presunto responsable de 49 ejecutados en Cadereyta, NL". Milenio (in Spanish). 18 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Mosso, Ruben (21 May 2012). "El Lazca y El Z40 ordenaron el multihomicidio". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- "Detienen a "El Loco" por masacre de Cadereyta". El Economista (in Spanish). 19 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- "Mutilados, detenciones y narcofosas podrían estar ligados". Milenio (in Spanish). 19 May 2012. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Los asesinatos de Cadereyta se ordenaron para causar confusión". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 21 May 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- "El Ejército detiene a presunto asesino de 49 personas en Cadereyta, NL". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 20 May 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- Althaus, Dudley (23 May 2012). "Suspect arrested in Mexico massacre". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- Otero, Silvia (18 May 2012). "Sedena: suman 5 fosas en China, Nuevo León". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Alzaga, Ignacio (19 May 2012). "Cae "El Loco", ligado a la masacre en Cadereyta". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Hallan 5 fosas en NL con al menos igual número de cuerpos calcinados". La Jornada (in Spanish). 18 May 2012. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- "El Ejército localiza cinco fosas en una carretera en Nuevo León". CNNMéxico (in Spanish). 18 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- "Cae presunto participante en asesinato de 49 personas en NL". Televisa (in Spanish). 3 August 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- Ignacio, Alzaga (4 August 2012). "Cae presunto autor de masacre en Cadereyta". Milenio (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- "Piden no enviar a la fosa común a descuartizados de Cadereyta". Proceso (in Spanish). 30 July 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2012.