Cancer pain

Pain in cancer may arise from a tumor compressing or infiltrating nearby body parts; from treatments and diagnostic procedures; or from skin, nerve and other changes caused by a hormone imbalance or immune response. Most chronic (long-lasting) pain is caused by the illness and most acute (short-term) pain is caused by treatment or diagnostic procedures. However, radiotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy may produce painful conditions that persist long after treatment has ended.

The presence of pain depends mainly on the location of the cancer and the stage of the disease.[1] At any given time, about half of all people diagnosed with malignant cancer are experiencing pain, and two thirds of those with advanced cancer experience pain of such intensity that it adversely affects their sleep, mood, social relations and activities of daily living.[1][2][3]

With competent management, cancer pain can be eliminated or well controlled in 80% to 90% of cases, but nearly 50% of cancer patients in the developed world receive less than optimal care. Worldwide, nearly 80% of people with cancer receive little or no pain medication.[4] Cancer pain in children and in people with intellectual disabilities is also reported as being under-treated.[5]

Guidelines for the use of drugs in the management of cancer pain have been published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and others.[6][7] Healthcare professionals have an ethical obligation to ensure that, whenever possible, the patient or patient's guardian is well-informed about the risks and benefits associated with their pain management options. Adequate pain management may sometimes slightly shorten a dying person's life.[8]

Pain

Pain is classed as acute (short term) or chronic (long term).[9] Chronic pain may be continuous with occasional sharp rises in intensity (flares), or intermittent: periods of painlessness interspersed with periods of pain. Despite pain being well controlled by long-acting drugs or other treatment, flares may occasionally be felt; this is called breakthrough pain, and is treated with quick-acting analgesics.[10]

The majority of people with chronic pain notice memory and attention difficulties. Objective psychological testing has found problems with memory, attention, verbal ability, mental flexibility and thinking speed.[11] Pain is also associated with increased depression, anxiety, fear, and anger.[12] Persistent pain reduces function and overall quality of life, and is demoralizing and debilitating for the person experiencing pain and for those who care for them.[10]

Pain's intensity is distinct from its unpleasantness. For example, it is possible through psychosurgery and some drug treatments, or by suggestion (as in hypnosis and placebo), to reduce or eliminate the unpleasantness of pain without affecting its intensity.[13]

Sometimes, pain caused in one part of the body feels like it is coming from another part of the body. This is called referred pain.

Pain in cancer can be produced by mechanical (e.g. pinching) or chemical (e.g. inflammation) stimulation of specialized pain-signalling nerve endings found in most parts of the body (called nociceptive pain), or it may be caused by diseased, damaged or compressed nerves, in which case it is called neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain is often accompanied by other feelings such as pins and needles.[14]

The patient's own description is the best measure of pain; they will usually be asked to estimate intensity on a scale of 0–10 (with 0 being no pain and 10 being the worst pain they have ever felt).[10] Some patients, however, may be unable to give verbal feedback about their pain. In these cases you must rely on physiological indicators such as facial expressions, body movements, and vocalizations such as moaning.[15]

Cause

About 75 percent of cancer pain is caused by the illness itself; most of the remainder is caused by diagnostic procedures and treatment.[16]

Tumor-related

Tumors cause pain by crushing or infiltrating tissue, triggering infection or inflammation, or releasing chemicals that make normally non-painful stimuli painful.

Invasion of bone by cancer is the most common source of cancer pain. It is usually felt as tenderness, with constant background pain and instances of spontaneous or movement-related exacerbation, and is frequently described as severe.[17][18] Rib fractures are common in breast, prostate and other cancers with rib metastases.[19]

The vascular (blood) system can be affected by solid tumors. Between 15 and 25 percent of deep vein thrombosis is caused by cancer (often by a tumor compressing a vein), and it may be the first hint that cancer is present. It causes swelling and pain in the legs, especially the calf, and (rarely) in the arms.[19] The superior vena cava (a large vein carrying circulating, de-oxygenated blood into the heart) may be compressed by a tumor, causing superior vena cava syndrome, which can cause chest wall pain among other symptoms.[19][20]

When tumors compress, invade or inflame parts of the nervous system (such as the brain, spinal cord, nerves, ganglia or plexa), they can cause pain and other symptoms.[17][21] Though brain tissue contains no pain sensors, brain tumors can cause pain by pressing on blood vessels or the membrane that encapsulates the brain (the meninges), or indirectly by causing a build-up of fluid (edema) that may compress pain-sensitive tissue.[22]

Pain from cancer of the organs, such as the stomach or liver (visceral pain), is diffuse and difficult to locate, and is often referred to more distant, usually superficial, sites.[18] Invasion of soft tissue by a tumor can cause pain by inflammatory or mechanical stimulation of pain sensors, or destruction of mobile structures such as ligaments, tendons and skeletal muscles.[23]

Pain produced by cancer within the pelvis varies depending on the affected tissue. It may appear at the site of the cancer but it frequently radiates diffusely to the upper thigh, and may refer to the lower back, the external genitalia or perineum.[17]

Diagnostic procedures

Some diagnostic procedures, such as lumbar puncture (see post-dural-puncture headache), venipuncture, paracentesis, and thoracentesis can be painful.[24]

Treatment-related

Potentially painful cancer treatments include:

- immunotherapy which may produce joint or muscle pain;

- radiotherapy, which can cause skin reactions, enteritis, fibrosis, myelopathy, bone necrosis, neuropathy or plexopathy;

- chemotherapy, often associated with chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy, mucositis, joint pain, muscle pain, and abdominal pain due to diarrhea or constipation;

- hormone therapy, which sometimes causes pain flares;

- targeted therapies, such as trastuzumab and rituximab, which can cause muscle, joint or chest pain;

- angiogenesis inhibitors like bevacizumab, known to sometimes cause bone pain;

- surgery, which may produce post-operative pain, post-amputation pain or pelvic floor myalgia.

Infection

The chemical changes associated with infection of a tumor or its surrounding tissue can cause rapidly escalating pain, but infection is sometimes overlooked as a possible cause. One study[25] found that infection was the cause of pain in four percent of nearly 300 people with cancer who were referred for pain relief. Another report described seven people with cancer, whose previously well-controlled pain escalated significantly over several days. Antibiotic treatment produced pain relief in all of them within three days.[17][26]

Management

Cancer pain treatment aims to relieve pain with minimal adverse treatment effects, allowing the person a good quality of life and level of function and a relatively painless death.[27] Though 80–90 percent of cancer pain can be eliminated or well controlled, nearly half of all people with cancer pain in the developed world and more than 80 percent of people with cancer worldwide receive less than optimal care.[28]

Cancer changes over time, and pain management needs to reflect this. Several different types of treatment may be required as the disease progresses. Pain managers should clearly explain to the patient the cause of the pain and the various treatment possibilities, and should consider, as well as drug therapy, directly modifying the underlying disease, raising the pain threshold, interrupting, destroying or stimulating pain pathways, and suggesting lifestyle modification.[27] The relief of psychological, social and spiritual distress is a key element in effective pain management.[6]

A person whose pain cannot be well controlled should be referred to a palliative care or pain management specialist or clinic.[10]

Coping strategies

The way a person responds to pain affects the intensity of their pain (moderately), the degree of disability they experience, and the impact of pain on their quality of life. Strategies employed by people to cope with cancer pain include enlisting the help of others; persisting with tasks despite pain; distraction; rethinking maladaptive ideas; and prayer or ritual.[29]

Some people in pain tend to focus on and exaggerate the pain's threatening meaning, and estimate their own ability to deal with pain as poor. This tendency is termed "catastrophizing".[30] The few studies so far conducted into catastrophizing in cancer pain have suggested that it is associated with higher levels of pain and psychological distress. People with cancer pain who accept that pain will persist and nevertheless are able to engage in a meaningful life were less susceptible to catastrophizing and depression in one study. People with cancer pain who have clear goals, and the motivation and means to achieve those goals, were found in two studies to experience much lower levels of pain, fatigue and depression.[29]

People with cancer who are confident in their understanding of their condition and its treatment, and confident in their ability to (a) control their symptoms, (b) collaborate successfully with their informal carers and (c) communicate effectively with health care providers experience better pain outcomes. Physicians should therefore take steps to encourage and facilitate effective communication, and should consider psychosocial intervention.[29]

Psychosocial interventions

Psychosocial interventions affect the amount of pain experienced and the degree to which it interferes with daily life;[3] and the American Institute of Medicine[31] and the American Pain Society[32] support the inclusion of expert, quality-controlled psychosocial care as part of cancer pain management. Psychosocial interventions include education (addressing among other things the correct use of analgesic medications and effective communication with clinicians) and coping-skills training (changing thoughts, emotions, and behaviors through training in skills such as problem solving, relaxation, distraction and cognitive restructuring).[3] Education may be more helpful to people with stage I cancer and their carers, and coping-skills training may be more helpful at stages II and III.[29]

A person's adjustment to cancer depends vitally on the support of their family and other informal carers, but pain can seriously disrupt such interpersonal relationships, so people with cancer and therapists should consider involving family and other informal carers in expert, quality-controlled psychosocial therapeutic interventions.[29]

Medications

The WHO guidelines[6] recommend prompt oral administration of drugs when pain occurs, starting, if the person is not in severe pain, with non-opioid drugs such as paracetamol, dipyrone, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or COX-2 inhibitors.[6] Then, if complete pain relief is not achieved or disease progression necessitates more aggressive treatment, mild opioids such as codeine, dextropropoxyphene, dihydrocodeine or tramadol are added to the existing non-opioid regime. If this is or becomes insufficient, mild opioids are replaced by stronger opioids such as morphine, while continuing the non-opioid therapy, escalating opioid dose until the person is painless or the maximum possible relief without intolerable side effects has been achieved. If the initial presentation is severe cancer pain, this stepping process should be skipped and a strong opioid should be started immediately in combination with a non-opioid analgesic.[27] However, a 2017 Cochrane Review found that there is no high-quality evidence to support or refute the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) alone or in combination with opioids for the three steps of the three-step WHO cancer pain ladder and that there is very low-quality evidence that some people with moderate or severe cancer pain can obtain substantial levels of benefit within one or two weeks.[33]

Some authors challenge the validity of the second step (mild opioids) and, pointing to their higher toxicity and low efficacy, argue that mild opioids could be replaced by small doses of strong opioids (with the possible exception of tramadol due to its demonstrated efficacy in cancer pain, its specificity for neuropathic pain, and its low sedative properties and reduced potential for respiratory depression in comparison to conventional opioids).[27]

More than half of people with advanced cancer and pain will need strong opioids, and these in combination with non-opioid pain medicine can produce acceptable analgesia in 70–90 percent of cases. Morphine is effective in relieving cancer pain.[34] Side effects of nausea and constipation are rarely severe enough to warrant stopping of treatment.[34] Sedation and cognitive impairment usually occur with the initial dose or a significant increase in dosage of a strong opioid, but improve after a week or two of consistent dosage. Antiemetic and laxative treatment should be commenced concurrently with strong opioids, to counteract the usual nausea and constipation. Nausea normally resolves after two or three weeks of treatment but laxatives will need to be aggressively maintained.[27] Buprenorphine is another opioid with some evidence of its efficacy but only low quality evidence comparing it to other opioids.[35]

Analgesics should not be taken "on demand" but "by the clock" (every 3–6 hours), with each dose delivered before the preceding dose has worn off, in doses sufficiently high to ensure continuous pain relief. People taking slow-release morphine should also be provided with immediate-release ("rescue") morphine to use as necessary, for pain spikes (breakthrough pain) that are not suppressed by the regular medication.[27]

Oral analgesia is the cheapest and simplest mode of delivery. Other delivery routes such as sublingual, topical, transdermal, parenteral, rectal or spinal should be considered if the need is urgent, or in case of vomiting, impaired swallow, obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract, poor absorption or coma.[27] Current evidence for the effectiveness of fentanyl transdermal patches in controlling chronic cancer pain is weak but they may reduce complaints of constipation compared with oral morphine.[36]

Liver and kidney disease can affect the biological activity of analgesics. When people with diminishing liver or kidney function are treated with oral opioids they must be monitored for the possible need to reduce dose, extend dosing intervals, or switch to other opioids or other modes of delivery.[27] The benefit of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be weighed against their gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal risks.[16]

Not all pain yields completely to classic analgesics, and drugs that are not traditionally considered analgesics but which reduce pain in some cases, such as steroids or bisphosphonates, may be employed concurrently with analgesics at any stage. Tricyclic antidepressants, class I antiarrhythmics, or anticonvulsants are the drugs of choice for neuropathic pain. Such adjuvants are a common part of palliative care and are used by up to 90 percent of people with cancer as they approach death. Many adjuvants carry a significant risk of serious complications.[27]

Anxiety reduction can reduce the unpleasantness of pain but is least effective for moderate and severe pain.[37] Since anxiolytics such as benzodiazepines and major tranquilizers add to sedation, they should only be used to address anxiety, depression, disturbed sleep or muscle spasm.[27]

Interventional

If the analgesic and adjuvant regimen recommended above does not adequately relieve pain, additional options are available.[38]

Radiation

Radiotherapy is used when drug treatment is failing to control the pain of a growing tumor, such as in bone metastasis (most commonly), penetration of soft tissue, or compression of sensory nerves. Often, low doses are adequate to produce analgesia, thought to be due to reduction in pressure or, possibly, interference with the tumor's production of pain-promoting chemicals.[39] Radiopharmaceuticals that target specific tumors have been used to treat the pain of metastatic illnesses. Relief may occur within a week of treatment and may last from two to four months.[38]

Neurolytic block

A neurolytic block is the deliberate injury of a nerve by the application of chemicals (in which case the procedure is called "neurolysis") or physical agents such as freezing or heating ("neurotomy").[40] These interventions cause degeneration of the nerve's fibers and temporary interference with the transmission of pain signals. In these procedures, the thin protective layer around the nerve fiber, the basal lamina, is preserved so that, as a damaged fiber regrows, it travels within its basal lamina tube and connects with the correct loose end, and function may be restored. Surgically cutting a nerve severs these basal lamina tubes, and without them to channel the regrowing fibers to their lost connections, a painful neuroma or deafferentation pain may develop. This is why the neurolytic is preferred over the surgical block.[41]

A brief "rehearsal" block using local anesthetic should be tried before the actual neurolytic block, to determine efficacy and detect side effects.[38] The aim of this treatment is pain elimination, or the reduction of pain to the point where opioids may be effective.[38] Though the neurolytic block lacks long-term outcome studies and evidence-based guidelines for its use, for people with progressive cancer and otherwise incurable pain, it can play an essential role.[41]

Cutting or destruction of nervous tissue

Surgical cutting or destruction of peripheral or central nervous tissue is now rarely used in the treatment of pain.[38] Procedures include neurectomy, cordotomy, dorsal root entry zone lesioning, and cingulotomy.

Cutting through or removal of nerves (neurectomy) is used in people with cancer pain who have short life expectancy and who are unsuitable for drug therapy due to ineffectiveness or intolerance. Because nerves often carry both sensory and motor fibers, motor impairment is a possible side effect of neurectomy. A common result of this procedure is "deafferentation pain" where, 6–9 months after surgery, pain returns at greater intensity.[42]

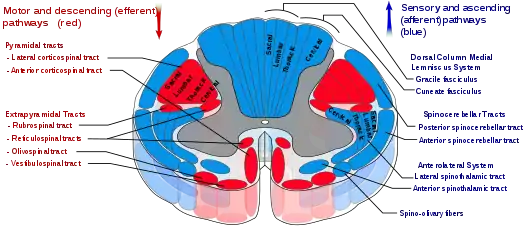

Cordotomy involves cutting nerve fibers that run up the front/side (anterolateral) quadrant of the spinal cord, carrying heat and pain signals to the brain.

Pancoast tumor pain has been effectively treated with dorsal root entry zone lesioning (destruction of a region of the spinal cord where peripheral pain signals cross to spinal cord fibers); this is major surgery that carries the risk of significant neurological side effects.

Cingulotomy involves cutting nerve fibers in the brain. It reduces the unpleasantness of pain (without affecting its intensity), but may have cognitive side effects.[42]

Hypophysectomy

Hypophysectomy is the destruction of the pituitary gland, and has reduced pain in some cases of metastatic breast and prostate cancer pain.[42]

Patient-controlled analgesia

- Intrathecal pump

- An external or implantable intrathecal pump infuses a local anesthetic such as bupivacaine and/or an opioid such as morphine and/or ziconotide and/or some other nonopioid analgesic as clonidine (currently only morphine and ziconotide are the only agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for IT analgesia) directly into the fluid-filled space (the subarachnoid cavity) between the spinal cord and its protective sheath, providing enhanced analgesia with reduced systemic side effects. This can reduce the level of pain in otherwise intractable cases.[38][42][43]

- Long-term epidural catheter

- The outer layer of the sheath surrounding the spinal cord is called the dura mater. Between this and the surrounding vertebrae is the epidural space filled with connective tissue, fat and blood vessels and crossed by the spinal nerve roots. A long-term epidural catheter may be inserted into this space for three to six months, to deliver anesthetics or analgesics. The line carrying the drug may be threaded under the skin to emerge at the front of the person, a process called "tunneling", recommended with long-term use to reduce the chance of any infection at the exit site reaching the epidural space.[38]

Spinal cord stimulation

Electrical stimulation of the dorsal columns of the spinal cord can produce analgesia. First, the leads are implanted, guided by fluoroscopy and feedback from the patient, and the generator is worn externally for several days to assess efficacy. If pain is reduced by more than half, the therapy is deemed to be suitable. A small pocket is cut into the tissue beneath the skin of the upper buttocks, chest wall or abdomen and the leads are threaded under the skin from the stimulation site to the pocket, where they are attached to the snugly fitting generator.[42] It seems to be more helpful with neuropathic and ischemic pain than nociceptive pain, but current evidence is too weak to recommend its use in the treatment of cancer pain.[44][45]

Complementary and alternative medicine

Due to the poor quality of most studies of complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of cancer pain, it is not possible to recommend integration of these therapies into the management of cancer pain. There is weak evidence for a modest benefit from hypnosis; studies of massage therapy produced mixed results and none found pain relief after 4 weeks; Reiki, and touch therapy results were inconclusive; acupuncture, the most studied such treatment, has demonstrated no benefit as an adjunct analgesic in cancer pain; the evidence for music therapy is equivocal; and some herbal interventions such as PC-SPES, mistletoe, and saw palmetto are known to be toxic to some people with cancer. The most promising evidence, though still weak, is for mind-body interventions such as biofeedback and relaxation techniques.[10]

Barriers to treatment

Despite the publication and ready availability of simple and effective evidence-based pain management guidelines by the World Health Organization (WHO)[6] and others,[7] many medical care providers have a poor understanding of key aspects of pain management, including assessment, dosing, tolerance, addiction, and side effects, and many do not know that pain can be well controlled in most cases.[27][46] In Canada, for instance, veterinarians get five times more training in pain than do physicians, and three times more training than nurses.[47] Physicians may also undertreat pain out of fear of being audited by a regulatory body.[10]

Systemic institutional problems in the delivery of pain management include lack of resources for adequate training of physicians, time constraints, failure to refer people for pain management in the clinical setting, inadequate insurance reimbursement for pain management, lack of sufficient stocks of pain medicines in poorer areas, outdated government policies on cancer pain management, and excessively complex or restrictive government and institutional regulations on the prescription, supply, and administration of opioid medications.[10][27][46]

People with cancer may not report pain due to costs of treatment, a belief that pain is inevitable, an aversion to treatment side effects, fear of developing addiction or tolerance, fear of distracting the doctor from treating the illness,[46] or fear of masking a symptom that is important for monitoring progress of the illness. People may be reluctant to take adequate pain medicine because they are unaware of their prognosis, or may be unwilling to accept their diagnosis.[8] Failure to report pain or misguided reluctance to take pain medicine can be overcome by sensitive coaching.[27][46]

Epidemiology

Pain is experienced by 53 percent of all people diagnosed with malignant cancer, 59 percent of people receiving anticancer treatment, 64 percent of people with metastatic or advanced-stage disease, and 33 percent of people after completion of curative treatment.[48] Evidence for prevalence of pain in newly diagnosed cancer is scarce. One study found pain in 38 percent of people who were newly diagnosed, another found 35 percent of such people had experienced pain in the preceding two weeks, while another reported that pain was an early symptom in 18–49 percent of cases. More than one third of people with cancer pain describe the pain as moderate or severe.[48]

Primary tumors in the following locations are associated with a relatively high prevalence of pain:[49][50]

- Head and neck (67 to 91 percent)

- Prostate (56 to 94 percent)

- Uterus (30 to 90 percent)

- The genitourinary system (58 to 90 percent)

- Breast (40 to 89 percent)

- Pancreas (72 to 85 percent)

- Esophagus (56 to 94 percent)

All people with advanced multiple myeloma or advanced sarcoma are likely to experience pain.[50]

Legal and ethical considerations

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights obliges signatory nations to make pain treatment available to those within their borders as a duty under the human right to health. A failure to take reasonable measures to relieve the suffering of those in pain may be seen as failure to protect against inhumane and degrading treatment under Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[51] The right to adequate palliative care has been affirmed by the US Supreme Court in two cases, Vacco v. Quill and Washington v. Glucksberg, which were decided in 1997.[52] This right has also been confirmed in statutory law, such as in the California Business and Professional Code 22, and in other case law precedents in circuit courts and in other reviewing courts in the US.[53] The 1994 Medical Treatment Act of the Australian Capital Territory states that a "patient under the care of a health professional has a right to receive relief from pain and suffering to the maximum extent that is reasonable in the circumstances".[51]

Patients and their guardians must be apprised of any serious risks and the common side effects of pain treatments. What appears to be an obviously acceptable risk or harm to a professional may be unacceptable to the person who has to undertake that risk or experience the side effect. For instance, people who experience pain on movement may be willing to forgo strong opioids in order to enjoy alertness during their painless periods, whereas others would choose around-the-clock sedation so as to remain pain-free. The care provider should not insist on treatment that someone rejects, and must not provide treatment that the provider believes is more harmful or riskier than the possible benefits can justify.[8]

Some patients – particularly those who are terminally ill – may not wish to be involved in making pain management decisions, and may delegate such choices to their treatment providers. The patient's participation in his or her treatment is a right, not an obligation, and although reduced involvement may result in less-than-optimal pain management, such choices should be respected.[8]

As medical professionals become better informed about the interdependent relationship between physical, emotional, social, and spiritual pain, and the demonstrated benefit to physical pain from alleviation of these other forms of suffering, they may be inclined to question the patient and family about interpersonal relationships. Unless the person has asked for such psychosocial intervention – or at least freely consented to such questioning – this would be an ethically unjustifiable intrusion into the patient's personal affairs (analogous to providing drugs without the patient's informed consent).[8]

The obligation of a professional medical care provider to alleviate suffering may occasionally come into conflict with the obligation to prolong life. If a terminally ill person prefers to be painless, despite a high level of sedation and a risk of shortening their life, they should be provided with their desired pain relief (despite the cost of sedation and a possibly slightly shorter life). Where a person is unable to be involved in this type of decision, the law and the medical profession in the United Kingdom allow the doctor to assume that the person would prefer to be painless, and thus the provider may prescribe and administer adequate analgesia, even if the treatment may slightly hasten death. It is taken that the underlying cause of death in this case is the illness and not the necessary pain management.[8]

One philosophical justification for this approach is the doctrine of double effect, where to justify an act involving both a good and a bad effect, four conditions are necessary:[8][54]

- the act must be good overall (or at least morally neutral)

- the person acting must intend only the good effect, with the bad effect considered an unwanted side effect

- the bad effect must not be the cause of the good effect

- the good effect must outweigh the bad effect.

References

- Hanna M, Zylicz Z, eds. (1 January 2013). Cancer Pain. Springer. pp. vii & 17. ISBN 978-0-85729-230-8.

- Marcus DA (August 2011). "Epidemiology of cancer pain". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 15 (4): 231–4. doi:10.1007/s11916-011-0208-0. PMID 21556709. S2CID 11459509.

- Sheinfeld Gorin S, Krebs P, Badr H, Janke EA, Jim HS, Spring B, et al. (February 2012). "Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in patients with cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 30 (5): 539–47. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0437. PMC 6815997. PMID 22253460.

- Hanna M, Zylicz Z (2013). "Introduction". In Hanna M, Zylicz Z (eds.). Cancer pain. Springer. p. 1. ISBN 9780857292308. LCCN 2013945729.

- Millard, Samantha K.; de Knegt, Nanda C. (December 2019). "Cancer Pain in People With Intellectual Disabilities: Systematic Review and Survey of Health Care Professionals". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 58 (6): 1081–1099.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.07.013. ISSN 0885-3924. PMID 31326504.

- WHO guidelines:

- World Health Organization (1996). Cancer pain relief. With a guide to opioid availability (2 ed.). Geneva: WHO. ISBN 978-92-4-154482-5.

- World Health Organization (1998). Cancer pain relief and palliative care in children. Geneva: WHO. ISBN 978-92-4-154512-9.

- Other clinical guidelines:

- "Opioids in palliative care: safe and effective prescribing of strong opioids for pain in palliative care of adults". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. May 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-07-03. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- "Consensus statement – Symptom management in cancer: Pain, depression and fatigue". USA National Institutes of Health. 2002. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- "Recommendations: morphine and alternative opioids for cancer pain". European Association for Palliative Care. 2001. Archived from the original on 2012-03-30. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- "Control of pain in adults with cancer". Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2008. Archived from the original on 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2011-08-22.

- "Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: adult cancer pain" (PDF). USA National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-22.(registration required)

- Randall F (2008). "Ethical issues in cancer pain management". In Sykes N, Bennett MI, Yuan CS (eds.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 93–100. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- Portenoy RK, Conn M (23 June 2003). "Cancer pain syndromes". In Bruera ED, Portenoy RK (eds.). Cancer Pain: Assessment and Management. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-521-77332-4.

- Induru RR, Lagman RL (July 2011). "Managing cancer pain: frequently asked questions". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 78 (7): 449–64. doi:10.3949/ccjm.78a.10054. PMID 21724928. S2CID 19598761.

- Kreitler S, Niv D (July 2007). "Cognitive impairment in chronic pain". Pain: Clinical Updates. XV (4). Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- Bruehl S, Burns JW, Chung OY, Chont M (March 2009). "Pain-related effects of trait anger expression: neural substrates and the role of endogenous opioid mechanisms". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 33 (3): 475–91. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.12.003. PMC 2756489. PMID 19146872.

- Melzack R & Casey KL (1968). "Sensory, motivational and central control determinants of chronic pain: A new conceptual model". In Kenshalo DR (ed.). The skin senses: Proceedings of the first International Symposium on the Skin Senses, held at the Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas. pp. 423–443.

- Kurita GP, Ulrich A, Jensen TS, Werner MU, Sjøgren P (January 2012). "How is neuropathic cancer pain assessed in randomised controlled trials?". Pain. 153 (1): 13–7. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.013. PMID 21903329. S2CID 38733839.

- Potter, Patricia Ann (2016-02-25). Fundamentals of nursing. Potter, Patricia Ann,, Perry, Anne Griffin,, Hall, Amy (Amy M.),, Stockert, Patricia A. (Ninth ed.). St. Louis, Mo. ISBN 9780323327404. OCLC 944132880.

- Portenoy RK (June 2011). "Treatment of cancer pain". Lancet. 377 (9784): 2236–47. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60236-5. PMID 21704873. S2CID 1654015.

- Twycross R, Bennett M (2008). "Cancer pain syndromes". In Sykes N, Bennett MI, Yuan CS (eds.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 27–37. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- Urch CE, Suzuki R (2008). "Pathophysiology of somatic, visceral, and neuropathic cancer pain". In Sykes N, Bennett MI, Yuan CS (eds.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- Koh M, Portenoy RK (2010). Bruera ED, Portenoy RK (eds.). Cancer Pain Syndromes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–85. ISBN 9780511640483.

- Gundamraj NR, Richmeimer S (January 2010). "Chest Wall Pain". In Fishman SM, Ballantyne JC, Rathmell JP (eds.). Bonica's Management of Pain. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1045–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6827-6. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- Foley KM (2004). "Acute and chronic cancer pain syndromes". In Doyle D, Hanks G, Cherny N, Calman K (eds.). Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. Oxford: OUP. pp. 298–316. ISBN 0-19-851098-5.

- Fitzgibbon & Loeser 2010, p. 34

- Fitzgibbon & Loeser 2010, p. 35

- International Association for the Study of Pain Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine Treatment-Related Pain

- Gonzalez GR, Foley KM, Portenoy RK (1989). "Evaluative skills necessary for a cancer pain consultant". American Pain Society Meeting, Phoenix Arizona.

- Bruera E, MacDonald N (May 1986). "Intractable pain in patients with advanced head and neck tumors: a possible role of local infection". Cancer Treatment Reports. 70 (5): 691–2. PMID 3708626.

- Schug SA, Auret K (2008). "Clinical pharmacology: Principles of analgesic drug management". In Sykes N, Bennett MI, Yuan CS (eds.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 104–22. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G (December 2008). "Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature". Annals of Oncology. 19 (12): 1985–91. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdn419. PMC 2733110. PMID 18632721.

- Porter LS, Keefe FJ (August 2011). "Psychosocial issues in cancer pain". Current Pain and Headache Reports. 15 (4): 263–70. doi:10.1007/s11916-011-0190-6. PMID 21400251. S2CID 37233457.

- Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ (September 1983). "The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment". Pain. 17 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(83)90125-2. PMID 6226916. S2CID 21533907.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education (2011). Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Gordon DB, Dahl JL, Miaskowski C, McCarberg B, Todd KH, Paice JA, et al. (July 2005). "American pain society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management: American Pain Society Quality of Care Task Force". Archives of Internal Medicine. 165 (14): 1574–80. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.14.1574. PMID 16043674. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA, McNicol ED, Bell RF, Carr DB, et al. (July 2017). "Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for cancer pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: CD012638. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012638.pub2. PMC 6369931. PMID 28700091.

- Wiffen PJ, Wee B, Moore RA (April 2016). "Oral morphine for cancer pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD003868. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003868.pub4. PMC 6540940. PMID 27105021.

- Schmidt-Hansen M, Bromham N, Taubert M, Arnold S, Hilgart JS (March 2015). "Buprenorphine for treating cancer pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD009596. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd009596.pub4. PMC 6513197. PMID 25826743.

- Hadley G, Derry S, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ (October 2013). "Transdermal fentanyl for cancer pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD010270. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010270.pub2. PMC 6517042. PMID 24096644.

- Price DD, Riley JL, Wade JB (2001). "Psychophysical approaches to measurement of the dimensions and stages of pain". In Turk DC, Melzack R (eds.). Handbook of pain assessment. NY: Guildford Press. p. 65. ISBN 1-57230-488-X.

- Atallah JN (2011). "Management of cancer pain". In Vadivelu N, Urman RD, Hines RL (eds.). Essentials of pain management. New York: Springer. pp. 597–628. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-87579-8. ISBN 978-0-387-87578-1.

- Hoskin PJ (2008). "Radiotherapy". In Sykes N, Bennett MI, Yuan CS (eds.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 251–55. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- Scott Fishman; Jane Ballantyne; James P. Rathmell (January 2010). Bonica's Management of Pain. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1458. ISBN 978-0-7817-6827-6. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- Williams JE (2008). "Nerve blocks: Chemical and physical neurolytic agents". In Sykes N, Bennett MI, Yuan CS (eds.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 225–35. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- Cosgrove MA, Towns DK, Fanciullo GJ, Kaye AD (2011). "Interventional pain management". In Vadivelu N, Urman RD, Hines RL (eds.). Essentials of pain management. New York: Springer. pp. 237–299. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-87579-8. ISBN 978-0-387-87578-1.

- Stearns L, Boortz-Marx R, Du Pen S, Friehs G, Gordon M, Halyard M, et al. (2005). "Intrathecal drug delivery for the management of cancer pain: a multidisciplinary consensus of best clinical practices". The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 3 (6): 399–408. PMID 16350425.

- Johnson MI, Oxberry SG, Robb K (2008). "Stimulation-induced analgesia". In Sykes N, Bennett MI, Yuan CS (eds.). Clinical pain management: Cancer pain (2nd ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 235–250. ISBN 978-0-340-94007-5.

- Peng L, Min S, Zejun Z, Wei K, Bennett MI (June 2015). "Spinal cord stimulation for cancer-related pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD009389. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009389.pub3. PMC 6464643. PMID 26121600.

- Paice JA, Ferrell B (2011). "The management of cancer pain". Ca. 61 (3): 157–82. doi:10.3322/caac.20112. PMID 21543825. S2CID 8989759.

- "The problem of pain in Canada". Canadian Pain Summit. 2012. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J (September 2007). "Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years". Annals of Oncology. 18 (9): 1437–49. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm056. PMID 17355955.

- International Association for the Study of Pain (2009). "Epidemiology of Cancer Pain" (PDF). Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- Higginson IJ, Murtagh F (2010). "Cancer pain epidemiology". In Bruera, ED, Portenoy, RK (eds.). Cancer Pain. Cambridge University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-511-64048-3.

- Brennan F, Cousins FJ (September 2004). "Pain: Clinical Updates: Pain relief as a human right". Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- Lohman D, Schleifer R, Amon JJ (January 2010). "Access to pain treatment as a human right". BMC Medicine. 8: 8. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-8. PMC 2823656. PMID 20089155.

- Blinderman CD (February 2012). "Do surrogates have a right to refuse pain medications for incompetent patients?". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 43 (2): 299–305. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.09.003. PMID 22248789.

- Sulmasy DP, Pellegrino ED (March 1999). "The rule of double effect: clearing up the double talk". Archives of Internal Medicine. 159 (6): 545–50. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.6.545. PMID 10090110. S2CID 30189029.

Further reading

- Fitzgibbon DR, Loeser JD (2010). Cancer pain: Assessment, diagnosis and management. Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-60831-089-0.

| Classification |

|---|